I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

What part of accounting don’t they get?

Well last night’s Australian federal budget was a total disgrace. Which means I am either crazy or the most of the rest of the commentators are because they are all hailing it as wonderful piece of policy. Lately, I have increasingly been reading this claim that governments have to conduct “fully-funded spending” as some sort of icon of fiscal responsibility. The Australian treasurer said it repeatedly in his speech and in his following press interviews. Whenever I read or hear that idea I say quietly: What part of accounting don’t they get?

What is it about accounting that the Australian Treasurer doesn’t understand (or at least the Treasury officials advising him don’t want to admit)? More on that later but first some background.

The New York Times chose to publish this article on May 11, 2010 – Greece, Debt and a Lesson for the U.S. – which was written by one David Leonhardt, who has a bio which says he is a mathematician by training but now writes about economics. He should have brought his arithmetic skills to his economics because the reasoning is lacking.

Leonhardt wants to push the “Greek today, US tomorrow” barrow. He presents a pathetic case. His strategy is to manipulate the fears of those who he thinks do not understand anything at all about economics – the general public. He ends up revealing that he hasn’t much idea himself about the way different monetary systems operate (EMU and the fiat system of the US) function.

He probably succeeds in scaring himself with this debt explosion nonsense such is his level of ignorance.

So we get the standard “(t)he numbers on our federal debt are becoming frighteningly familiar”:

The debt is projected to equal 140 percent of gross domestic product within two decades. Add in the budget troubles of state governments, and the true shortfall grows even larger. Greece’s debt, by comparison, equals about 115 percent of its G.D.P. today.

The United States will probably not face the same kind of crisis as Greece, for all sorts of reasons. But the basic problem is the same. Both countries have a bigger government than they’re paying for. And politicians, spendthrift as some may be, are not the main source of the problem.

We, the people, are.

So from this you would understand that a rise in public debt reflects a government spending beyond its means – spendthrift behaviour. And you would form the view that a government should not do this because spendthrift behaviour is somehow wasteful, profligate (how many times have we read about the profligate Greeks in the last month – Answer: too many), indulgent – moralise away!

But there is no mention of what drives the deficit.

There is also no mention of the fact that the rise in public debt is a voluntary choice made by the government under pressure from the neo-liberal ideology. They could legislate not to increase debt anytime they could get away with it and nothing much would happen other than the debt ratio would start falling and become zero at some point in time.

And – most importantantly, there is no mention of the way in which the public deficit interacts and responds to behaviour in the other sectors of the economy (the external and private domestic sectors). I will come back to this later because it is a point that escaped the Australian Treasurer when he delivered last night’s federal budget.

You also get the conflation of levels of government – state and federal. The former using the currency that is issued by the latter. But no mention of that crucial difference.

You also get the conflation of monetary systems – EMU and fiat – the former denying any national government currency sovereignty the latter bestowing a very complete and powerful sovereignty on the national government. But no mention of that crucial difference.

So just from that opening gambit you would conclude that Mr Leonhardt is an economics illiterate. I don’t mean to be unkind but it is he who is putting his views out as one of an expert.

But the political point is clear – people elect governments. It just happens that there is not a level playing field in our democracies. The media is highly influential in shaping the opinions of the voters. And the top-end-of-town with the cash is able to infiltrate the political process in a myriad of ways to distort public perceptions and mis-represent policy choices etc.

Anyway, Leonhardt claims that the political process in the US is ambiguous:

We have not figured out the kind of government we want. We’re in favor of Medicare, Social Security, good schools, wide highways, a strong military – and low taxes. Dealing with this disconnect will be the central economic issue of the next decade, in Europe, Japan and this country.

So this is a disconnect that is confected. To construct this as a disconnect you have to make some assumptions. He doesn’t list them and maybe even doesn’t know he is making them – given his grasp of the material (note Europe and Japan and the US are run together as being equivalent).

The assumptions are that the US government is revenue constrained. But no sovereign government is ever revenue constrained because they issue the currency in use under monopoly conditions.

So the disconnect arises because the likes of Leonhardt run these smokescreens and people believe them.

Anyway, Leonhardt then lectures us on fiscal restraint and how politically unpopular it is when it comes to actually dealing with the public spending excesses.

The message seems clear: woe unto the politician – in Washington, Athens or London – who tries to go beyond platitudes and show some actual fiscal restraint.

This situation obviously can’t continue, as Robert Greenstein, perhaps the leading liberal budget expert, points out. Mr. Greenstein’s politics make him sympathetic to the worry that all the deficit talk will become an excuse to pull back on stimulus spending while unemployment remains high or to gut social programs. But he also knows the numbers well enough to understand that our Greece moment, whether it takes the form of a crisis or not, is coming.

“our Greece moment” – what a lovely (meaningless) turn of phrase. The US will never have a Greece moment in that the government is facing bankruptcy. The US government has no risk of insolvency. If it continues to issue debt to match its deficits then the bond yields demanded by the markets may rise. If the US government doesn’t like that it can issue debt in the short-maturity range only and allow the Federal Reserve to control yields (more or less).

The Greek government has no such opportunities or capacities available to it.

Greenstein, who is the Director of the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, which is “a nonprofit policy institute that conducts research and analysis on fiscal policy matters and an array of federal and state programs and policies” recently gave Testimony on the Need to Implement a Balanced Approach to Addressing the Long-Term Budget Deficits before the US Committee on Ways and Means, Subcommittee on Select Revenue Measures.

His summary points for the US fiscal situation were:

… our current fiscal path is simply unsustainable over the longer term. Federal deficits and debt will rise to unprecedented and dangerous levels if current policies remain unchanged …

Digging ourselves out of this predicament will require action on both sides of the budget … We will not be able either to finance the kind of government that Americans want …

Congress should try to get deficits down to about 3 percent of GDP by mid-decade. Deficits at that level would keep the debt from rising as a share of the economy and thus would go a long way toward reassuring our creditors and putting the budget on a more sustainable path.

You get the drift. He tries to appear progressive (and reasonable) in his testimony by arguing that the Ways and Means Committee “aspires to a debt-to-GDP ratio of 60 percent (which implies deficits of about 2.3 percent of GDP), whereas we think that a 70 percent debt-to-GDP ratio (with deficits around 3 percent of GDP) is sustainable”.

Neither ratio has any real meaning. Greenstein is a deficit dove and they are part of the problem.

But Greenstein and Leonhardt are transfixed on the “long-term deficit” which will grow because:

As societies become richer, citizens tend to want better schools, better medical care and other government services. This country is following that pattern, but without paying the necessary taxes. That combination has us on a course to Greece-like debt.

Rising tax revenue will not increase the real resources available to the economy. Rising tax revenue reduces the access that the private sector has to existing real resources and thus allows the government sector to have increased access.

This has nothing to do with the taxes funding the government spending. Taxes function to create idle real resources which can then be deployed by the government. But there has to be real resources available in the first place.

So as societies become richer and citizens want more government services etc – then they will be able to have them if (a) the real resources necessary to deliver these services are available; and (b) the political compromise is consistent. Neither of these conditions have anything to do with the number next to the fiscal deficit at any point in time.

The US government will always be able to purchase what is available for sale in US dollars if it thinks the politics are amenable. This is so whether they are running surpluses or deficits of whatever magnitude you want to write down on a piece of paper.

The long-term problem is about productivity, real resource availability and productive capacity. None of those things are going to be helped by running austerity programs now. Quite the opposite.

Leonhardt continues to argue about the need for tax hikes and spending cuts and matching spending with taxes – to make sure the US “pays for what it spends”. He thinks this will be “unpleasant” but not spell “doom”.

He concludes that “(w)e need to make choices” and then quotes one Alan Krueger, who is the chief economist at the US Treasury Department:

It’s not a matter of whether we have the resources to solve our problems … It’s a matter of political will.

With a chief economist like that no wonder economic policy making in the US is so dismal. The truth is that “it is all a matter of whether the US has the (real) resources to solve their problems … and then it becomes a political issue as to where those resources are allocated”.

But Leonhardt’s notion that governments have to make sure they “pay for their spending” is a recurring theme. Of-course, it implies a balanced budget. It is also based on an implicit notion that the government is like a household and cannot go on spending more than it earns.

Well, if someone would do me a favour and E-mail Leonhardt and give him the good news.

The US government like all sovereign governments can always spend more than it earns – continuously and indefinitely – because the concept of “earning” is redundant. Unlike a household or a corporation, the sovereign government doesn’t need to earn to spend. That is a fundamental part of having a fiat currency system.

It might hide behind institutions (like debt-issuance mechanisms) and rhetoric (like we are running out of money) but the operational reality is that behind all these smokescreens – the US government is not revenue-constrained.

But the point goes deeper than this. Trying to prescribe rules about fiscal conduct – like the US government should “pay for its spending” – as stand-alone behavioural constraints – misses the point that the fiscal balance is largely endogenous. Endogenous to what? To the behaviours of the other sectors.

In other words, inflexible fiscal rules that sound fine to the puritanical brigade are unlikely to represent responsible fiscal management when applied to the ultimate goals of government activity – to advance public purpose.

Being specific – if the private domestic sector wanted to spend exactly the same amount it earned and the external accounts were balanced at all times (exports = imports adjusted for invisibles) then the government could run a balanced budget without damaging national income. Whether this was a full employment spending level overall would depend. If not, then the only way to advance higher GDP and employment growth would be to push the government into deficit, or the private sector in deficit or the external sector into surplus or some consistent combination of all three.

Australian Federal Budget

This issue came up constantly during the Australian budget speech last night. I wasn’t going to write anything about this dismal policy statement but the point has to be made by someone given how creepy the main commentary is today – like glowing endorsements of the fiscal responsibility that the government is displaying – that sort of nonsense.

The Treasurer’s Budget Speech to Parliament was full of misrepresentations and misunderstandings about the options his government has. He claimed that the Budget met “the highest standards of responsible economic management”. Why?

Every dollar of new policy in this Budget has been offset across the forward estimates, as we meet the strict confines of our responsible fiscal strategy.

A strategy that will see the budget return to surplus in three years time, three years ahead of schedule, and ahead of every major advanced economy.

A strategy that will pay off debt three years sooner – again ahead of every major advanced economy – without increasing taxes as a share of the economy beyond the level we inherited from our predecessors.

So Leonhardt could have written this speech.

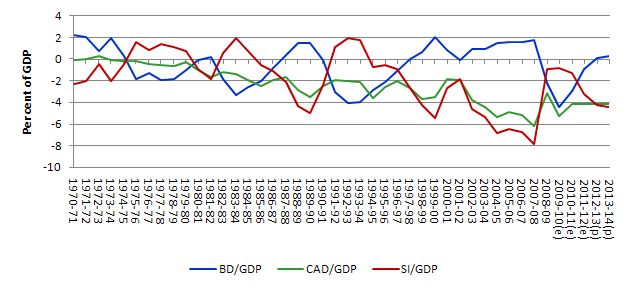

Consider the following analysis. The following graph is constructed from the official Australian budget data available in Statement 10: Historical Australian Government Data of Budget Paper No.1 and the RBA Statistical Bulletin for the external account data. The private domestic balance (SI/GDP) is derived as an analytical solution. All data is expressed as a percentage of GDP.

What is this analytical solution? Recall that the Sectoral Balances are derived from the National Accounts and summarise the flows in and out of each of the three sectors:

- The private domestic balance (S – I) is the excess of income over spending (conceptualised as the difference between saving and investment) and is positive if in surplus and negative if in deficit.

- The Budget Deficit (T – G) is the excess of spending (G) over revenue (T) and is negative if in deficit and positive if in surplus.

- The Current Account balance (X – M) is the difference between exports and imports (with adjustments for invisibles) and is positive if in surplus, negative if in deficit.

After some derivation (which I explain in this blog) we get the basic sectoral balances accounting statement – which is an alternative view of the national accounts (note the way I have presented it here is a little differently to the way I presented it in the blog referred to above):

(S – I) + (T – G) + (X – M) = 0

That is the three balances have to sum to zero as a matter of accounting. So in the graph, there is consistency of interpretation – ll deficits are below the zero line and all surpluses are above it – the budget deficit is constructed as a negative and a current account deficit is a negative and private domestic dissaving is a negative. That makes it easier to understand.

To understand how these balances move you have to introduce theories about the underlying behaviour of the sectors. But the manifestation of that behaviour is summarised by the balances and has to be true by definition.

These balances are usually expressed as a per cent of GDP but that doesn’t alter the accounting rules that they sum to zero, it just means the balance to GDP ratios sum to zero.

A simplification is to add (S – I) + (X – M) and call it the non-government sector. Then you get the basic result that the government balance equals exactly $-for-$ (absolutely or as a per cent of GDP) the non-government balance (the sum of the private domestic and external balances). This is also a basic rule derived from the national accounts and has to apply at all times. It is thus true as a matter of accounting.

As an aside, I was asked by two separate people while I was in Washington D.C. last month for the Financial Sustainability Teach-In how we computed the sectoral balances. They had both tried to use US Flow of Funds data and could not get the sectoral balances equation to solve. The reality is that the way in which the National Accounts data is presented (and the Flow of Funds data) you are unable to exactly match the concept of Saving minus Investment, which is the private sector balance. Hence you usually treat it as a solution to the sectoral balance equation as noted above.

The graph shows the Government balance (blue line), the Current Account balance (green line) and the private domestic balance (red line) from fiscal year 1970-71 to 2013-14. The results for 2009-10 to 2013-14 are projected. The budget deficit estimates are from the Government’s budget papers while I just took the average currenct account position since 2000 (average deficit of 4.7 per cent) and held it constant. It will probably worsen as economic growth strengthens which will mean the private balance will record a higher deficit than otherwise.

The relationships you observe are clear. As the neo-liberal mania for federal surpluses took over from 1996 to 2007, the private saving balance fell dramatically. There was a slight downward trend in the current account position driven by the stronger than average growth. The growth was initially fuelled (up until 2005) by the credit-binge that accompanied the private deficits. The stock manifestation of these flows was the rapid escalation of private sector indebtedness.

You can see that the return to deficit from 2008 onwards helped fund the private domestic sector’s desire to increase its saving ratio and the private domestic balance has been heading to surplus in the current period.

So then consider the government’s resolve to push the budget back into surplus as quickly as possible. Even with a stable current account deficit (green line) this move (if backed by behaviour capable of achieving the desired outcome) will push the private domestic sector back into increasing deficit which also means increased indebtedness.

We went into the crisis with a desperate need for the private sector to reduce its record levels of indebtedness and we are coming out of it again with a government intent on frustrating this requirement for financial stability.

I know they don’t think in these terms but what part of accounting don’t they understand?

Perhaps their advisors are telling them that the mining boom will be so strong that the external sector will move into surplus and support both private domestic saving overall and the projected budget surpluses. That will be an extraordinary outcome if it occurs. Even with record terms of trade and strong volume demand in the lead up to the crisis, the current account did not go towards surplus – the deficit actually increased as growth strengthened as you would expect.

So the other scenario is that the private sector resists the pressure to resume the credit-binge and consumption and investment do not grow much. Even with some growth coming via exports, the net impact of the external sector will be to drain growth (such is an external deficit) and with the government sector contracting, overall GDP growth will falter.

The Budget was also marked by the so-called fiscal virtue of imposing fiscal rules on government. The Treasurer said in his Budget Speech last night:

Mr Speaker, I also announce tonight an extension of our fiscal strategy. A new phase, focused on building even stronger surpluses and paying off debt even quicker. The Government will maintain the 2 per cent annual cap on real spending growth, on average, until the surplus reaches 1 per cent of GDP.

On current projections, this would be achieved in 2015-16.

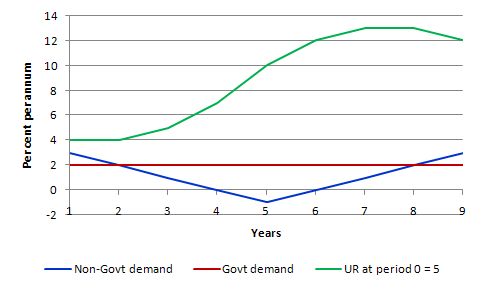

Fiscal rules are dangerous because they try to impose an exogeneity on the budget balance in denial of the other spending aggregates in the economy. Consider this simple example depicted in the following graph. The standard rule of thumb is that real GDP growth has to at least equal the sum of the labour force growth rate plus the labour productivity growth rate (both assumed to be 2 per cent per annum in this example). I model non-government real spending growth (red line) as a cycle and impose the 2 per cent government fiscal spending rule. GDP growth is the sum of the two.

I start off with an unemployment rate of 5 per cent and then model the course of unemployment as actual GDP growth evolves given the non-government and government spending growth behaviour. You can see that when non-government spending growth falls the fiscal rule results in a rapid rise in the unemployment rate.

The point is that these sorts of rules will always fail if there is any political concern about declining living standards and unemployment. So why impose them in the first place only to be forced to relax or abandon them after they have done their damage (as we are witnessing in Europe at present)?

Then we came to the worst part of the Budget Speech.

In Budget Paper No 1, Chapter 2 The Economic Outlook we read on Page 2-31:

Continued momentum in the labour market is expected to see the unemployment rate fall to around its full employment level over the forecast horizon … The unemployment rate is expected to fall to 5 per cent in the June quarter 2011 and 4¾ per cent in the June quarter 2012.

This led the Treasurer to say in his speech that:

Best of all, the unemployment rate is expected to fall further from 5.3 per cent today to 4¾ per cent by mid-2012, around the level consistent with full employment.

So we have NAIRU-par excellence operating here.

In my view this was the worst sentence in the whole Budget Speech. The current state of the Australian labour market is summarised HERE.

At present, 12.5 per cent of our willing labour resources are idle – either unemployed (5.3 per cent) or underemployed (7.2 per cent). GDP growth has to be of the order of 4 per cent per annum or more to start eliminating this waste. At the height of the last boom, Australia was could only achieve a low-point labour underutilisation rate of around 9 per cent of our available workers (either unemployed or underemployed). While labour lay idle and essential public infrastructure decayed, the government extolled the virtues of its surpluses.

It is true that the current downturn was much less severe than first thought and a large credit goes to the early and significant fiscal intervention followed by the recovery in China, which was also the product of an even large fiscal intervention. We are calling it a mining boom while the Chinese are calling it fiscally-responsible leadership.

But then going into the downturn we were a long way from being at full employment – 9 per cent of your labour resources laying idle is not full employment. At that point the official unemployment rate was around 4 per cent and demand-pull inflation was stable (there were price pressures arising from imported petrol prices and drought cause food shortages).

First, why is an official unemployment rate of 4.75 per cent now the NAIRU whereas we were well below that in February 2008. No insights are provided in the Budget Papers. The answer is that modelling variability will have pumped out that number and the Treasury officials wrote it down and Treasurer Swan mindlessly passed it on to us. The more salient point is that the models are flawed in the extreme and shouldn’t be trusted.

The following blogs provide a critique of the – The dreaded NAIRU is still about! – and the biased modelling that derives these sort forecasts – Structural deficits – the great con job! – Structural deficits and automatic stabilisers – Another economics department to close.

Second, there was zero focus on underemployment in the Budget Papers and Speech. Does the fact that 7.3 per cent of willing Australian workers are not working enough hours represent wastage?

If the official unemployment rate drops to 4.75 per cent, then underemployment may drop to around 6.75 or 7 per cent. The trend, however, is to increasingly create part-time work in our economy and this militates towards rising unemployment.

So, since when does full employment, which used to mean full capacity, coincide with around 11.5 per cent or thereabouts of your available labour not working enough hours, some not working at all?

Which inflation adjustment models are giving that result? The Treasury inflation model does not allow for underemployment in the price setting process. It thus grossly overestimates the unemployment rate that is consistent with stable inflation – even using its own flawed logic that computes this mythical equilibrium.

Third, the Budget Papers show that the government is forecasting a modest decrease in the participation rate over the forward estimates – so the rise in hidden unemployment that occurred over the downturn will not be reversed. This further negates their claim that they will achieve full employment.

The reality is that the Australian government is continuing to abandon one of its primary responsibilities – to ensure there are enough jobs and working hours to match the preferences of the labour force.

Its solution to this policy failure is to redefine full employment. That is how the neo-liberals have been able to justify running economies at well below capacity for more than 30 years now while deregulating the hell out of them and transferring real output increasingly to the rich.

The Australian government is part of the process and has abandoned any claim to fiscal responsibility – which starts with ensuring the budget sustains aggregate demand such that the economy generates and maintains true full employment.

Media reaction

Here is a collection of responses. I must be living in another land – that is the only conclusion I can reach.

Hartcher, Sydney Morning Herald (Source):

The Rudd Government has delivered a zen budget – it’s more about what’s not happening than what is happening … But old-fashioned prudence is vital for the national interest in a world that’s increasingly panicking over governments in debt.

Gittins, Sydney Morning Herald (Source):

WILL wonders never cease? Economic rectitude with only a modicum of pain. With one leap Labor gets the budget back on track. It should be back in surplus in 2012-13, three years earlier than expected

Gratten, Sydney Morning Herald (Source):

A RAPID return to surplus and the prospect of full employment underpin a restrained federal budget aimed at showcasing the Rudd government’s economic management

Megalogenis, The Australian (Source)

This is a reasonable budget for a revenue recovery. The cap on spending allows the revenue gains to pour into the bottom line.

Shanahan, The Australian (Source)

THERE’S only one number that counts in Wayne Swan’s pre-election budget – $1 billion – that’s the surplus in 2013 and the foundation for the 2010 election campaign.

And the worst of them all came from Jessica Irvine, Sydney Morning Herald (Source):

The bloodstain on the budget balance inflicted by the global financial crisis is fading … economic growth is heading back to boom time and the nation’s jobless rate, once tipped to hit 8.5 per cent, is now expected to fall below 5 per cent. That’s good news for workers but brings us to the one cloud on the otherwise sunny economic horizon. Such a low jobless rate is ominously below the level that most economists say is compatible with keeping inflation at a moderate pace … It’s an ugly wart on what is otherwise a very pretty set of numbers.

The only critical perspective came from the CEO of the St Vincent de Paul Society Dr John Falzon who argued that the budget forced the unemployed and sole parents to live below the poverty line and maintain the fractured society that the conservatives had set up in the last decade or more.

Good on you John, flying the flag for the disadvantaged as always.

Conclusion

The Budget is a total disgrace.

Anyway, my band is playing tonight so …

That is enough for today!

Dear Bill

Have you ever been a presenter at an accounting conference? They may be the only group of people who would really get your ideas in a big way. Getting word out to thousands of accountants could be the kick start needed to raise this up to a national level. Perhaps offering to write an article for a big accounting magazine is another option.

The nature of the comments by the media goes exactly to what I have been banging on about – this budget is likely to score some desperately needed political brownie points for a government on the eve of an election with it’s popularity severely flagging.

Up until last night, a hostile and partisan media had been engaging in a relentless campaign of remarkable fear-mongering, hysteria and even defamation, obviously designed to inflict maximum damage on the government – I have certainly never seen anything quite like it. In fact, so brazen are some of the half-truths and exaggerations and so ruthless has the pursuit of them been that I am tempted to think that what the media in Australia have been doing is viciously and spitefully engaging in a war against fiscal activism – the insulation and BER programs have borne the brunt of astonishing hysterical attacks made without the slightest attempt to present any context and ridiculous accusations (such as inferring major organised crime involvment). These attacks have been highly effective – some programmes have been shut down and the governments former commanding poll lead has been decimated. The media have “proven” that big government spending programmes always f*** up severly.

But last nights budget has (temporarily at least) changed that. The media are largely approving of the budget – something the government would have seen as crucial, given their current standing in the polls as they prepare to go to election. The kind of budget that MMT proponents would be more approving of would have been instantly shredded by the press and it’s bloody viscera spattered across the papers and commercial news.

And with that, any hope of re-election would have been destroyed. So even if they do understand how the modern fiat monetary economy that they are presiding over functions, we got something like the budget we were always going to get.

Government budgets are driven at least as much by the need for political manouvering as they are by anything else, including any notion of advancement of the public purpose.

Sad but true.

Apologies for being slightly off-topic but I spotted something in today’s UK Guardian that might be of interest to Prof Mitchell and the posters here:

http://www.guardian.co.uk/business/2010/may/12/spanish-pm-debt-crisis-emergency-cuts

The article says that the Spanish PM, Mr Zapatero, “saved money with budget surpluses during his first term in office”. Could these “savings” have anything to do with Spain’s current 20% unemployment rate?

“They could legislate not to increase debt anytime they could get away with it and nothing much would happen other than the debt ratio would start falling and become zero at some point in time.”

Wouldn’t the currency just tank against the dollar, causing a massive rise in fuel prices?

Is there solid evidence this *wouldn’t* happen?

Also are you sure that an increase in stimulus would indeed cause output to increase and not just prices. My accountancy training shows that the best way to increase profits is to put your prices up – particularly if you have a demand wave hitting you.

Just trying to work through the effects of government deficit spending without the issuance of bonds to drain excess reserves from the settlements system:

The plus is that governments would not have debt they could be attacked over and would be free of accusations of mortgaging our children’s future and all various other kinds of nonsense.

The downside would be an increase in bank assets that are excess reserves, not loans. Eventually the quantity of excess reserves could become very large indeed. The banks would earn whatever the interest rate the central bank pays on excess reserves but this would be less than what the banks could earn on loans. Presumably bank profits would decrease as a result, so they would raise fees, lower interest rates paid on deposits, lower dividend payments and squeeze bank workers.

It seems to me the non-issuance of bonds is not an entirely free lunch. Am I missing something here?

Leonhardt: “We have not figured out the kind of government we want. We’re in favor of Medicare, Social Security, good schools, wide highways, a strong military – and low taxes.”

Another self-refutation. 😉

Neil: The Aus$ would only tank if foreigners dumped their stocks of Aus$. Why would they do this in response to our issuing less bonds? As for solid evidence, Japanese governments have been doing just that for a decade and their exchange rate is fine. There may be fluctuations when the news first hits, but then exports would drive the Aus$ right back up. Also, prices are sticky – especially when there is competition. Unless your company has a monopoly or a cartel, it’s a better strategy to first produce more instead of raising prices. All over the world stimuluses have increased output (or rather, prevented output from falling too much). Inflation has not been a problem.

Bill, you write, “The long-term problem is about productivity, real resource availability and productive capacity.” This is pretty much what neoliberals and Austrians accuse Keynesians of all stripes and MMT’ers in particular of ignoring by focusing on the demand side. They trumpet that they are concerned with “the long term” problem and that requires focusing on productivity, real resource availability and productive capacity – all supply side. Since this is an argument I hear against MMT, I’d like to see a rebuttal of this objection, if you think it worth putting on your list.

Dear Tom,

There is no contradiction with what Bill is saying in the quote above and MMT as I understand it. The concept of what is full employment needs to be identified in order to determine the effectiveness of fiscal policy and inflationary pressures. To his list, as I have argued before, we must include issues of structural constraints in transactions and production as well as what I call “Resource Inadequacies”. This a concept to identify the potential for reorganization and innovation that resources have even if they are fully employed. Its productivity under pressure! Its a qualitative index that can allow growth without inflation even after full employment is reached.

“Also, prices are sticky – especially when there is competition. Unless your company has a monopoly or a cartel, it’s a better strategy to first produce more instead of raising prices.”

That simply isn’t true. Firstly increased demand due to a stimulus means that the supply side is constrained. That shifts the balance of power to the supplier. Prices can be increased within quite a large range because supplier relationships tend to be sticky – particularly if there is an artificial demand wave. If you’ve ever struggled to get on a corporate ‘approved supplier’ list you’ll know what I mean.

You can get much more profit by top slicing your turnover with increased prices than you can with all the effort of gearing up production (or incidentally slashing costs). It’s a simply matter of accounting.

Dear Takis,

I was not implying that there is a contradiction in MMT. It is an objection that I hear, and it is not something that I have MMT’ers address head on. Perhaps they have, but I have not seen it.

This recalls Scott’s complaining the other day about a misperception of MMT as concerned with national accounting and sectoral balances. That is incorrect, but it is the impression that a lot of people criticizing MMT have.

I’m trying to understand MMT as a comprehensive macro approach for use in policymaking, along with references, so I can present this important understanding better.

@tom

I think a key concept of Bill’s work is that the most important long-term resource constraint is skilled workers, and that the way you get skilled workers is by having people in jobs. So, the best way to solve the problem of real resource constraints is to make sure everyone is in work. Seen from that perspective, MMT is fundamentally about ‘real’ constraints rather than accounting ones.

This blog post of Bill’s about the NAIRU addresses this.

https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=1502

The issue of skilled workers is important. However, we must also pay attention to the fact that structural constraints and friction are variable and can be removed with discretionary fiscal policy such as infrastructure projects. Furtermore, attention must be placed to the issue that productivity and resource inadequacies are real, variable and respond to inflationary pressures that cause reorganization and innovation of the use of existing resources in order to reduce inflationary risks. There is a resource adequacy to protect against inflation risk. So a growth model, must incorporate an adjustment term for productivity change variation to keep inflation to the minimum.

Neil: You mention an “artificial demand wave”. How can a company know if increased sales are being bought with stimulus dollars or regular dollars? If it’s because they watch the news and see a stimulus package and think, “this will all blow over, i’m gonna raise prices!” then surely such long term thinkers will also not lay off any workers in a recession because that will blow over as well.

Why does a stimulus mean that supply is constrained? Because a stimulus only occurs in bad times? If the economy is tanking, thats because of insufficient demand, not because companies can’t produce enough goods.

If what you say is true, then in your economy, any increased demand is inflationary, whether its from ‘fake stimulus dollars’ or from ‘honest growing economy’ dollars.

I’m sorry but I find this “lack of skills” line of reasoning a bit on the nose.

Why not look at it from the other side ? Namely, that there are a lack of jobs matching the skillset of those that are unemployed?

Wayne Swan has a job and he has no skills – but fortunately for him the government created a postion for the most economically illiterate individual in the country and named it “Treasurer”.

Hence, if the government can create a job for someone like Wayne Swan or the other imbeciles that preceded him then why shouldn’t they do it for everyone else that wants to work ?

A street busker has skills and yet according to the formalised definition many here go upon they are unskilled. That’s the governments fault not the buskers.

…. and the list goes on.

Playing the game by the rules the conservatives laid down is a recipe for disaster. MMT needs to differentiate itself fom them but all I see is MMT becoming more and more like them.

Meet the new boss same as the old boss.

While doing a keyword search online, I randomly bumped into this article:

“Certainly, balancing the budget is a commendable policy goal, but support for it must be based on other criteria than concern over interest rates.”

Do Budget Deficits Raise LT Interest Rates?

February 2002.

Cato institute.

Some “friends” where you least expect them?

“You also get the conflation of levels of government – state and federal.”

Is it accurate to say that a US state keeps an account at a private bank, not the CB?

“You also get the conflation of monetary systems – EMU and fiat”

The analogy has been made before, that a EMU member can be thought of as a US state. Yet the ECB is the fiscal agent of a EMU member. I’m confused and have asked more specific questions here:

http://moslereconomics.com/2010/05/10/eu-lends-to-itself-to-bail-itself-out-ecb-remains-sidelined/comment-page-1/#comment-19908

Thanks.

“Why does a stimulus mean that supply is constrained? Because a stimulus only occurs in bad times? If the economy is tanking, thats because of insufficient demand, not because companies can’t produce enough goods.”

And that is the rub, getting the amount of stimulus correct. If a business drops demand, and then this picks up yet the papers are full of quantitative easing and doom mongering then they will do nothing more than take up their slack and not expand. Expansion requires confidence, and having the government pumping money into the system – with the consequential pressure on the currency exchange doesn’t give confidence. Much better to put up prices, dampen off demand and pocket the difference.

I can only see stimulation taking up the undestroyed slack in the economy if that. It can’t buy confidence.

Having said that it may be that stimulation of private sector companies is a bad idea – because of the confidence issue. Perhaps the Job Guarantee is a better idea – as people get laid off, then more graffiti gets cleaned up.

Dear Tom at 2:13 pm

You wrote:

But you cannot assume that the demand and supply sides are independent. That is the classic mistake of orthodox analysis. The supply side affects the demand side in many ways. So the long-term problem is exploiting the interdependencies to ensure we have enough available to sustain employment and high living standards and enough spending to realise those goals.

best wishes

bill

Neil: You are right, that is yet another reason a JG is far better than a stimulus. A stimulus is temporary and encourages quick price gouging like the kind you describe, while a JG suggests government-driven demand is here to stay, so you better start expanding or fall behind!

Alan Dunn says:

“Wayne Swan has a job and he has no skills – but fortunately for him the government created a postion for the most economically illiterate individual in the country and named it “Treasurer”.”

I’m puzzled as to how anyone could regard Wayne Swan as the most economically illiterate individual in the country after what Barnaby Joyce said a few weeks ago!

Bill says: The US government has no risk of insolvency. If it continues to issue debt to match its deficits then the bond yields demanded by the markets may rise. If the US government doesn’t like that it can issue debt in the short-maturity range only and allow the Federal Reserve to control yields (more or less).

I can see that government is not revenue constrained and that spending must proceed injection of liquidity (turning up in ‘Tin Shed’ as increased currency or increased bank reserves). So the extra bank reserves represent extra liquidity in the system that can be drained by issuance of bonds or short-maturity instruments. The quote seems to imply that bonds have a different impact to short-term maturity debt. Can someone explain this for me? And isn’t the extra liquidity returned to the system upon maturity of the financial instruments which ever way you go? Isn’t taxation the only way to permanently drain the liquidity?

Bill,

I am trying to fully understand the relationships between the current account, private sector, and government sector balances. Based on my quiz results over the past few months, I am not progressing as quickly as I would hope. Anyway, I have a question that has to do with the sectoral balance equation and the graph of the Australian sectoral balances from 1970 through 2014. The graphed balances do not to sum to zero based on the equation (S-I) + (T-G) + (X-M) = 0. For 2008, the government surplus is 2%, the current account balance is -6% and the private sector balance is -8%. These do not sum to zero, as expected from the equation as written. They do sum to zero, if the current account balance is reversed to (M-X). So, isn’t the correct relationship, for the balances to sum to zero, (S-I) + (T-G) + (M-X)?

Also, thanks for writing this blog, it has helped me immensely. I work with a regional environmental non-profit in the US and attended a conference on my state’s electric utility industry prospects a few months ago. One of the environmental speakers begin their presentation with a slide showing the projected US deficit. I thought it quite strange for an environmentalist to start a presentation on the environmental challenges for the electric utility industry by stating that society will have large future deficits and have limited choices based on financing limitations. I had a hard time focusing on the remainder of the presentation – it was clear that with this as a starting point for the environmentalist, they would not be asking for much in the way of environmental investments and improvement. I also decided that it was time to learn about deficits and the other “economic constraints” which are used to publicly dismiss investments in jobs and technologies which would provide real economic and environmental benefits.

Your blog has shown that these constraints are, today, almost completely self-inflicted and cause significant public harm. Thanks for the education!

Regards,

David Wright