I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Ladies and gentleman, civilisation is ending

Today I wasted 20 minutes reading about the end of the World. But before I did that I read some so-called progressive literature that was calling on the UK government in tomorrow night’s budget to seek a balanced budget. You say what? That’s right, what goes for progressive thought these days is what used to be the exemplar of fiscal conservativism not so long ago. While the current crisis exposed most of the myths that mainstream economists have promoted for years it seems that progressives are not seizing the day but trying to sound more reasonable (read: right-wing conservative) than the conservatives. The crisis has also pushed all these opinionated loonies like Niall Ferguson into prominence. Its getting pretty lonely out here …. wherever I am (and don’t say the left word)! (<= joke).

First, those ever so reasonable progressives

Consider the following graphs constructed using UK data – the net public borrowing as a per cent of GDP from data provided by HM Treasury and the unemployment rate data from the OECD Main Economic Indicators database.

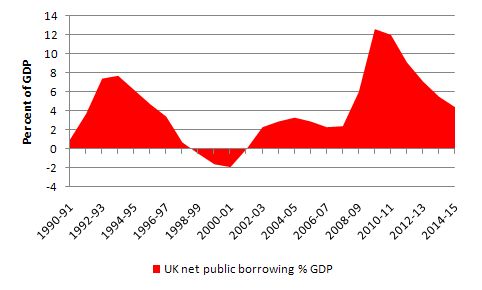

The first graph was published recently by the so-called UK Progressive Economics Panel in a paper entitled – Testing Times – which purports to be a progressive commentary on the options facing the UK government in the Budget to be delivered tomorrow (Wednesday).

I reproduced their Figure 1 which they introduced in this way:

This paper does not seek to engage in the broader debate about whether budget deficits are good or bad, rather it is premised on a belief that sometimes budget deficits are necessary (as was the case during the economic downturn) but that over the course of the business cycle (the ups and downs of economic activity), public finances need to be balanced in order to remain sustainable.

As can be seen in Figure 1, the UK’s budget deficit (defined here as public sector net borrowing) is substantial.

First, note the time period – 1990/91 to 2013/14. Very selective indeed. If you compare the situation at the end of the known data period (last financial year) with previous peaks provided by the full data set (which begins in 1964/65) then the current period 6.0 per cent is overshadowed by the peaks in 1975/76 (7 per cent) and 1993/94 (7.7 per cent). Certainly the projections are that by the end of this financial year the net borrowing to GDP ratio (which is a measure of the deficit) will go beyond 10 per cent such is the parlous state of the UK economy.

Remember that it as just endured the record number of consecutive quarters of negative GDP growth (that is, its longest recession) in its known history.

Second, note the colour – inflamed red! Nothing subdued about that. I am sure the marketing and advertising experts out there can inform us about colour and suggestion in graphical production.

Third, note from their accompanying description, this so-called progressive position is really just rehearsing the mainstream economic position that the national government deficit should be balanced over the business cycle without any reference to anything else. It is presented as a standalone requirement.

Which means this so-called progressive position is nothing of the sort. It just perpetuates the mainstream economics myths that focus on the budget number (scaled by GDP or not) as if it is a meaningful construct in its own right, independent of other information.

The fact is that you can say very little about a deficit to GDP ratio without knowing what else is going on.

Remember that deficits are endogenous and driven by non-government spending. The automatic stabilisers ensure that is the case. The UK is unlikely to be an external surplus nation anytime over the next several years. It has been in deficit on the current account virtually continuously since 1982. That structural disposition will not change much over the next decade whatever other rhetoric you read.

So that is important information. What it tells you is that there is a net drain on UK national expenditure via the external sector. We also know that the private domestic sector in the UK has been on a debt binge over the last decade which fed a huge real estate boom. That sector is now deleveraging (too slowly but it is) and is being supported by the public deficits.

The point these progressives don’t seem to understand – an ignorance they share with the mainstream economists who tout the balanced budget over the cycle as if it sounds reasonable – is the following: under the circumstances that the UK economy is in (external surpluses), if the govenrment could actually engineer fiscal policy (and the state of the economy) to deliver a balanced fiscal position averaged over some cycle, then they would also be forcing the private domestic sector into deficits on average equal to the external deficits.

That means increasing levels of private sector indebtedness. It is highly unlikely that they would be able to achieve these fiscal outcomes anyway before the economy collapsed even further.

But not only would be a nonsensical short-run fiscal strategy, given the debt levels the UK private sector is carrying at present, it would not be a sustainable growth policy in the medium-term. Eventually the private balance sheets would become too fragile and households etc would attempt to increase saving – which then would reduce aggregate demand further and income adjustments would force the public balance back into deficit. It would only be a matter of time.

Finally, the term fiscal sustainability is one of the most bandied about terms at present. Even these alleged “progressives” have just bought the line “public finances need to be balanced in order to remain sustainable”. If that was true then public finances in most countries since World War 2 (for which we have data) were unsustainable – during the 30 years of full employment and stable growth public deficits were the norm – supporting private saving desires while keeping output and employment growth strong enough to absorb the growing labour forces.

The fact is that equating “balance” with sustainability sounds reasonable until you understand the underlying relationships. Then you realise that there is no such equation. What the appropriate fiscal position should be depends on private saving desires and the structure and performance of the external sector. It is highly unlikely that these influences will deliver a fully employed economy with a balanced budget.

No progressive analyst who understands macroecoomics and the way modern monetary systems operate would dare to consider the concept of fiscal sustainability independent of the state of the labour market and other important social and environmental indicators. The endogeneity of the public budget just “measures” these other considerations and has not meaning in and of itself.

For a clearer understanding of what the term involves you might like to read these blogs – Fiscal sustainability 101 – Part 1 – Fiscal sustainability 101 – Part 2 – Fiscal sustainability 101 – Part 3.

So I recommend that the UK Progressive Economics Panel should disband forthwith due to its gross misrepresentation of the progressive agenda and its manifest ignorance of matters they purport to be expert about. Can someone in London give then a call and tell them to close up shop please?

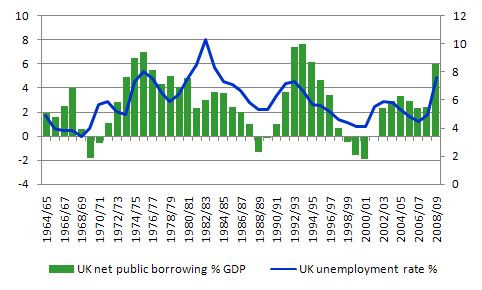

Given all that, consider the next graph which extends the sample to use all the HM Treasury data currently available that is known (that is, ends at 2008-09) and adds the national unemployment rate. I also change the colours to make them less strident.

First, note that every time the UK government has achieved a budget surplus (green bars below zero line) a recession (or major downturn in labour market performance) has followed.

Second, extending the sample to include the mid-1970s recession also provides a different perspective on the current situation. One could argue that the rising deficits now, which will persist for some years, have been instrumental in stopping the unemployment rate from rising further. Equally, attempts to cut back prematurely, which will almost certainly be announced in London tomorrow, will cause the same sort of unemployment spike that occurred during the mid-1970s.

Third, the dynamics of the budget deficit are driven by the evolution of the unemployment rate. I could have fiddled with quarterly data with some finer attention to lags to bring that relationship even more into relief. But even at the annual data periodicity, you can see it clearly.

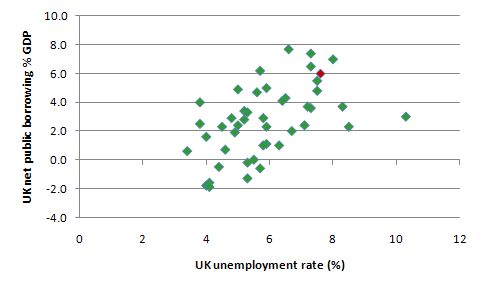

The next graph shows the scatter plot between the UK unemployment rate (horizontal axis) and the UK net public borrowing as a per cent of GDP (vertical axis). The red marker is the last fiscal year (2008-09) and is right in the midst of the other observations. It is very clear that rising unemployment driven by a fall in aggregate spending will drive up deficits. So what?

The progressive position should be to focus on the unemployment rather than the numbers on a spreadsheet!

Then I read the UK Sunday Times (March 21, 2010) where conservative Dominic Lawson wrote – Do the right thing before you go, Alistair Darling. In terms of mis-informed commentary this is about as bad as it gets.

The tenor of the argument is that the UK civil servants are lazy fat cats (“distended state’s employees”) who have not suffered job losses in the crisis and should have and that their whining greedy ways have caused “the great majority of the extraordinary increase in public expenditure” in recent years and the budget deficit to “blow out”.

The guy is a real charmer.

Whether there should be a public war on the UK public sector unions which he is promoting is another debate. But it is the macroeconomics that he uses to buttress his case which is the most disturbing.

He claims that it is clear that there has been a “decline in productivity in the public sector” because:

The official employment figures released last week merely underlined this impression: they showed the private sector shedding jobs at a rate of 1,440 per day over the past 12 months, while employment in the public sector actually rose over the same period.

Yes, the official data shows that but what has that to do with productivity? Answer: Nothing! It just demonstrates that during a recession the public sector is a more secure employer than the private sector. Which, in turn, means that the collapse of aggregate demand is attenuated by the continued spending power of the civil servants.

He doesn’t elaborate any further on that having “proved” his case to the unwitting public that read his diatribes.

The next target are those evil Keynesians:

Commentators calling themselves Keynesians also argue that it is necessary to maintain or even increase public expenditure for at least another year, so as to supply the necessary stimulus to an economy that would otherwise enter some sort of deflationary spiral.

Yet the wisdom of engaging in such a policy must surely depend on the existing state of the national finances. Maynard Keynes himself regarded it as unwise to have a national debt larger than 25% of gross domestic product. Yet we are now heading for a debt to GDP proportion of more than 100%, and even before the credit crunch and the banking bailout it had risen to nearly 50%.

Anyone who understands the way the income and expenditure operates would argue that it is necessary to continue supporting aggregate demand with public expenditure. Please read yesterday’s blog – Clowns to the left, jokers to the right – for more discussion on this point.

The term Keynesian is somewhat misleading. Please read my blog – Those bad Keynesians are to blame – to see how the term can mean many different things.

But the overwhelming point is that the period when the ideas of Keynes and the Keynesians constituted the dominant policy orthodoxy was almost entirely characterised by non-convertible monetary systems (first the gold standard and then the quasi US-based system of convertibility). By the mid-1970s, the Keynesian orthodoxy in macroeconomics had been usurped by the Monetarists which has morphed into other even more misguided forms in recent decades.

So anything Keynes said about fiscal balances has to be seen in that light. The convertible currency system placed constraints on fiscal policy such that governments had to fund their net spending. Please read my blog – Gold standard and fixed exchange rates – myths that still prevail – for more discussion on this point.

The UK government runs a fiat currency system – that is, one where there is no convertibility and a flexible exchange rate. That means these ratios that Lawson chooses to compare are not comparable. Even focusing on those ratios is an artefact of the convertible currency era.

He clearly doesn’t understand that. The point we have to continually remind ourselves of is this – there was a major break in monetary systems in 1971 and that changed the way fiscal policy operates and its limits.

Lawson then goes from bad to worse. He says that the “Keynesians” argue that:

… the greatest danger is that we do as America did in 1937. President Roosevelt cut back on public expenditure in that year, thinking that America’s recovery from the slump was solid. In the event, there was a further contraction of the economy and yet more unemployment, only arrested by the extraordinarily destructive stimulus known as the second world war.

Yet this analysis, which is also regularly aired in the leader columns of The Guardian, completely fails to take into account that over the past year, through the money-printing programme delicately termed “quantitative easing”, Britain has already expanded its monetary base threefold – an increase that took 50 years and two world wars to bring about in the first half of the last century.

First, FDR was not motivated by a thought that the growth path was solid. He was being constantly berated by conservative deficit terrorists (he himself was one) and finally gave into the pressure that was being put on him. Much the same is going on today and governments are running scared in just the same way that he did in 1936-37 – to the detriment of his citizens as history tells us.

Second, The Guardian is hardly a progressive media source these days.

Third, the analysis (that continuing fiscal support is required) does not “completely fail to take into account” the “quantitative easing” which has been occurring. The enlightened proponents of this “analysis” just demonstrate a superior understanding to that displayed by Lawson about the nature of “quantitative easing”.

As I have argued several times, the resort to quantitative easing was initially a reflection of the orthodox belief that monetary policy was the only effective aggregate macroeconomic policy tool available (having eschewed the use of fiscal policy for years). They also believed in flawed concepts such as the money multiplier and erroneously considered that if they added bank reserves the banks would lend them out. Of-course, banks do not lend out reserves – they use them to settle payments. And bank lending is never constrained by a lack of reserves anyway.

So as policy strategy to stimulate aggregate demand it could only work by reducing long-term interest rates (as assets were sold to the central banks and yields dropped accordingly). However, given the parlous state of business confidence even lower interest rates was not going to lead to a significant demand for renewed credit growth. It was a flawed strategy from the start.

Lawson still thinks that expanding the high powered money base is an expansion of aggregate demand. Some myths die slowly.

Please read the following blogs – Quantitative easing 101 – Building bank reserves will not expand credit and Building bank reserves is not inflationary – for further discussion.

To really put the icing on his cake of ignorance Lawson then says:

… the parallel that should truly scare us is not with America in 1937, but Greece in 2010. We have the same annual deficit, relative to the size of our economy, as precipitated the Greek sovereign debt crisis. That is why the British state is now having to pay more than the Italian government of Silvio Berlusconi as a coupon on its new debt – and this is debt being raised to pay the interest on our existing borrowings.

This is false causality. The reason new debt charges are rising in Britain is because the British government will not instruct (or enact law to allow it to instruct) the Bank of England to manage the yield curve at the maturities that it is issuing debt. That is why the bond markets have the traction they have. Once the Bank of England did that then the bond markets become irrelevant.

But the causa causans is the mindless maintenance of the gold standard/convertible currency relic that the sovereign British government has to issue debt before it can net spend. It never has to issue debt and should not. That is a basic precept of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) and reflects the fact that the old fiscal constraints the forced governments to issue debt to cover deficit spending are not longer binding. They are purely voluntary now.

So you ask – why would a government voluntarily retain an unnecessary arrangement especially when it causes them such political drama? Answer: ideology. The conservatives realising that the convertible system is gone had to come up with a new reason for debt issuance given their violent distaste for the alternative. So the new justification is all housed in the “fiscal sustainability” and “fiscal discipline” terminology.

Behind it there is nothing of substance. If we cannot trust governments to act wisely then these constraints are hardly relevant anyway.

Finally, as I have pointed out regularly – there is no comparison between Greece which is non-sovereign (doesn’t issue its own currency, doesn’t set its own monetary policy and cannot adjust via exchange rate movements) and the UK (which is the opposite of all those things). The continual conflation of monetary systems by these commentators just tells you that they don’t understand the differences and the implications of those differences.

Ladies and gentleman, it gets worse!

Anyway, my meander through the day’s financial press included a narrative that was predicting the end of the Western civilisation.

Local Sydney Morning Herald political editor Peter Hartcher, who gives the (false) impression to his readers that he knows something about economics, wrote today (March 23, 2010) about – An empire in decline as the world turns upside down – (thanks to Beau too!).

I knew it wouldn’t be about Star Trek or Star Wars or whatever. As an aside, I have never seen any of the Star*.* programs or movies. Not my taste! But I sort of know what they are about.

But Hartcher thinks he is looking into the end of the World himself. He says:

Evidence is accumulating that we have reached a civilisational turning point. The aftermath of the global financial crisis is showing strong signs it was the inflection point where the decline of the West accelerated and the rise of the great, new, poor powers became nearer and more assured.

History is quickening.

When the crisis broke out in 2008, the world already had a two-speed economy – the rich countries of the West were out for a gentle stroll while the rising poor countries were at a sprint. But both parts of that trend have sharpened now the acute phase of the crisis has passed, and both look set to sharpen yet further in the years ahead.

I love articles that start with phrases such as “evidence is accumulating”. Almost surely they are going to be comical in their substance. This is no exception.

So given Hartcher wouldn’t have done the research to go this deep where does he get his predictions of doom from? You guessed it – none other than the self-aggrandising doom merchant Niall Ferguson who in his latest article wrote that:

Imperial collapse may come much more suddenly than many historians imagine. A combination of fiscal deficits and military overstretch suggests that the United States may be the next empire on the precipice.

The article was published in the March/April 2010 Edition of Foreign Affairs but they will make you pay for it. You can read it from this aggregator – Complexity and Collapse – Empires on the Edge of Chaos

It is torrid going. A basic proposition is that “imperial expansion carries the seeds of future decline” and “great powers rise and fall according to the growth rates of their industrial bases and the costs of their imperial commitments relative to their GDPs”.

He cites the Mayans who:

… fell into a classic Malthusian trap as their population grew larger than their fragile and inefficient agricultural system could support. More people meant more cultivation, but more cultivation meant deforestation, erosion, drought, and soil exhaustion. The result was civil war over dwindling resources and, finally, collapse.

Yes, but that hasn’t anything to do with fiscal deficits and debt ratios. It has to do with a shortage of real goods and services relative to the need for them.

All government spending is constrained by the real resources available for sale. That is why the climate change debate is much more significant for the future of humanity than all this deficit-debt hoopla.

Observing that point though would be too difficult for Ferguson. He wants to build up the “collapse of civilisation” story and he knows that by the time he gets to his main angle the reader will have forgotten the specifics about the Mayans or the other examples he gives.

Ferguson then focuses on the “current economic challenges facing the United States” which he believes are more immediate than the most people think. He argues that the ageing population debate (health care/pensions etc) is artificially pushing our focus to the future as the “United States to sink deeper into the red”.

Of-course, MMT demonstrates that the ageing population debate is, in fact, a faux debate anyway. Ferguson and others always present it as a financial problem or issue. So: will governments be able to pay for things? Or afford things? In fact, the real policy issue is, more akin to the issues that caused the downfall of the Mayans – real resource availability and the political conflicts that may occur (deciding who gets health care).

All sovereign governments can always afford to buy whatever is for sale in their own currency. Whether they should is another matter but there is no financial constraint. That is just another conservative smokescreen.

Meagre detail for Ferguson. His main argument is that these long-term concerns may not reflect the way historical processes unfold and;

What if history is not cyclical and slow moving but arrhythmic — at times almost stationary, but also capable of accelerating suddenly, like a sports car? What if collapse does not arrive over a number of centuries but comes suddenly, like a thief in the night?

I am no historian so I cannot comment on the dynamics of historical processes from a professional perspective. What I can comment on though are the triggers that Ferguson proposes which will fast-track the collapse of the US empire.

I think that once you understand the mechanisms he is relying on to scare the bejesus out of Peter Hartcher and anyone else who thinks he should be taken seriously, then you will relax more easily tonight.

First, we get a rehearsal of chaos theory. Okay fine, butterflies set off floods.

Second, we get a rehearsal of “fat tail” events – “wars, revolutions, financial crashes, and imperial collapses”. Okay fine, these happen.

The point he wants to make is that civilisations collapse very quickly and are almost always:

… associated with fiscal crises. All the above cases were marked by sharp imbalances between revenues and expenditures, as well as difficulties with financing public debt. Alarm bells should therefore be ringing very loudly, indeed, as the United States contemplates a deficit for 2009 of more than $1.4 trillion — about 11.2 percent of GDP, the biggest deficit in 60 years — and another for 2010 that will not be much smaller. Public debt, meanwhile, is set to more than double in the coming decade, from $5.8 trillion in 2008 to $14.3 trillion in 2019. Within the same timeframe, interest payments on that debt are forecast to leap from eight percent of federal revenues to 17 percent.

So we get to the point. But if Ferguson’s theory was correct – why didn’t the US collapse in the 1940s or 1950s? All the fiscal “numbers” were in the same ballpark as now.

The point is that despite his claim to authority as an impeccable economic historian he fails to address the historical perspective that was available to him. Being highly selective in the historical episodes that you examine always is a sign that something is amiss.

I was actually expecting him to argue that the 1940s were different to now because most of the US debt was purchased by Americans and China was weak etc. But there was none of that. Why not? It wouldn’t help his argument to acknowledge that once growth resumed the “large” debt and deficit ratios fell steadily and life went on.

And this was in the context of the 1940s when the convertible currency monetary system constrained the US government’s capacity to manage fiscal policy much more severely than the fiat currency system does now.

But moreover, what does he think will happen? The US Government will “run out of money”? How would it ever do that? It is the monopoly-issuer of the US dollar and has been totally sovereign since 1971. It has never defaulted on any debt servicing or principle payments, even when it operated under convertibility.

Even if his projections are accurate, why will they start defaulting now? There is no fiscal crisis. The crisis that the US economy faces is a real one – lost jobs, lost productive capacity and a polity that appears incapable of dealing with that.

Ferguson claims that “the role of perception is just as crucial” as the “bad” numbers. In this regard he claims that what could easily set off a crisis is:

… one day, a seemingly random piece of bad news — perhaps a negative report by a rating agency — will make the headlines during an otherwise quiet news cycle. Suddenly, it will be not just a few policy wonks who worry about the sustainability of U.S. fiscal policy but also the public at large, not to mention investors abroad. It is this shift that is crucial: a complex adaptive system is in big trouble when its component parts lose faith in its viability.

The credit rating agencies downgraded Japan several times in the early 2000s with zero impact! The Japanese government just ignored them as the US government will ignore them if they get too far ahead of themselves. Eventually, national governments are going to outlaw these unproductive and unlawful institutions.

Further, even if the “investors abroad” get scared – so what? The US government doesn’t rely on this cohort. It is totally sovereign. Ultimately, if private investors back away, the US government has the capacity to ignore them and proceed to net spend as it sees fit. It might have to alter legislation or whatever (I am not an expert in the US legal code) but the financial fact is that it is totally sovereign and clothes itself in voluntary constraints that make it look otherwise.

Do you really think that these constraints will survive if the US empire is at stake?

Ferguson then chooses to rehearse Rational Expectations and Ricardian Equivalence type arguments that the most extreme mainstream economists still hang onto. He suggests that:

Neither interest rates at zero nor fiscal stimulus can achieve a sustainable recovery if people in the United States and abroad collectively decide, overnight, that such measures will lead to much higher inflation rates or outright default. As Thomas Sargent, an economist who pioneered the idea of rational expectations, demonstrated more than 20 years ago, such decisions are self-fulfilling: it is not the base supply of money that determines inflation but the velocity of its circulation, which in turn is a function of expectations. In the same way, it is not the debt-to-GDP ratio that determines government solvency but the interest rate that investors demand. Bond yields can shoot up if expectations change about future government solvency, intensifying an already bad fiscal crisis by driving up the cost of interest payments on new debt. Just ask Greece — it happened there at the end of last year, plunging the country into fiscal and political crisis.

Thomas Sargent did not pioneer the idea of rational expecations more than 20 years ago. That is factually incorrect. The ideas go back to the late 1950s and early 1960s and the most well-known early developer was John Muth. Sargent build extreme predictions based on the early work but was not a pioneer. Again, Ferguson exhibits poor scholarship.

Please read my blog – Deficits should be cut in a recession. Not! – for more discussion on why these theoretical constructs – Rational Expectations and Ricardian Equivalence – represent exemplars of intellectual poverty.

Further, as noted above, if the US government is facing damaging bond yields then it has the power to solve the problem itself. The central bank sets rates and can manage the yield curve out to any maturity. Further, the US government can alter the laws forcing it to issue debt. Please read my blog – Who is in charge? – for more discussion on this point.

So if empires are under threat I would expect to see a movement towards a more enlightened understanding of the opportunities the fiat monetary system presents the sovereign government rather than a passive and compliant descent into chaos as the bond markets made increasingly unreasonable demands.

Finally, note the G word creeps in. I wouldn’t ask Greece anything if I was seeking facts and developing options for the US. The monetary systems that the two nations operate within are incommensurate.

Ferguson then bats on about US foreign policy and the whole narrative descends into farce.

He should be disregarded. He is a mindless ideologue.

For Sydney Morning Herald readers, the fact that Hartcher seems happy to quote extensively from Ferguson without the slightest critical scrutiny of the central propositions being advanced – all of which are erroneos when applied to a sovereign government in a modern monetary system – should tell you that he should also be disregarded.

Conclusion

That is enough for today!

I agree, Hartcher had a shocker today (I can’t bring myseful to comment on Ferguson). He starts off by warning than ‘history is quickening’ and concluding by invoking the usual demographich argument about the slow and inevitable collapse of the West under the burden of healtcare costs. Not sure exactly why Hartcher is under the impression that this process is quickening now: the dynamics have been in place for years now.

Bill,

I don’t know about you, but I need more evidence that the evidence is accumulating.

Dear Bill,

Reading your blog I cannot help visualising MMT in the world, as something of a ‘golden thread’ through a labyrinth of neoclassical voodoo (concealing the half human – half bull, Wall St. minotaur at its core). Or contemplate the many headed hydra Hercules must slay, by lifting it aloft to the sunlight! To me, these imaginative parables speak eloquently of the human condition on planet earth.

It must seem like a nightmare sometimes, when at every twist and turn in the labyrinth there is a pundit or two or three, who sprout two heads every time he or she forfeits one, to babble dire predictions of ships of state torn asunder and whole nations of people lost to the sea; or worse, serve greedy egotists to help bind people to the maze and a life of insecurity and debt peonage – sometimes to the extent where even their most basic needs are ground into the dirt. If there was hell on earth for an economist who understands macroeconomics, and human potential, then surely the labyrinth would do!

The purpose of Theseus entering the labyrinth was to slay the minotaur and save the youth of Crete, thereby proving his lineage and courage as a worthy son of Poseidon. Everybody knew (unlike Congress today) that an unregulated half human half animal bull that rampaged freely over the countryside had to be contained. So something has changed for the worse there! Imagine Obama ‘riding the bull’ as in the Herculean tale, to the ‘mainland’ (Main St.).

Hercules, advised to “rise by kneeling, conquer by surrendering, gain by giving up” – slew the Lernaean nine-headed hydra. For those unfamiliar with the symbology of the story, three heads symbolise the appetites (sex, comfort and money); three the passions (fear, hatred and desire for power); three the unillumined mind (pride, separativeness and cruelty). Once slain, the one immortal head of power was buried “under the rock of persistent will” where its energy could be put to better use in lifting humanity. It took humility to stand steady, courage to face the hydra and recognise its strength and weakness, poise and discrimination to quit lopping off sacrificial heads, and strength to lift the hydra up into the sunlight – where separated from the slime and mud, it became so weakened it could be conquered. So, at least that much hasn’t changed!

In other words, our hero’s problems were simply tests of their humanity and the focus in each. And that was that! As all good parables go, they point to the minotaur and hydra in us all! Humanity is understood without pretence. Nowadays of course we have TV, where humanity is understood absolutely as pretence!

My thought is that mind is an incredibly powerful thing; concepts multiply like seeds listing on the winds, fuelled by competitive grasping egos – and with them multiply our perceived needs. Death comes and draws a line through it all leaving others to pursue blindly what others have conditioned them to pursue. ‘A few golden balls are rolled through the world’. Hardly anybody questions this? Well, science does but everybody is too busy to listen! But understanding (our true intelligence) is much, much more powerful – because in the human being who stops for just one moment, and turns around to face in the other direction, it is clearly seen – all needs lead back to one need. And that need is understood by the human heart long before it is understood by the uncontrolled mind (ask your wives)! Rationality (as I am sure will be much to the consternation of the rationalists who religiously believe in their chosen deity) has absolutely nothing to do with it! In the heart you will find a different kind of intelligence. In those in whom the minotaur and the hydra have been brought under control, you will find people who prefer equity, kindness and generosity for very self evident reasons. Pain and suffering have taught them direction, motivation and a different kind of consciousness and awareness of self. Rationality is anchored in one’s own humanity rather than in the mind. The heart has governance over the rationality (which usually wasn’t all that rational in the first place. (The other tasks of Hercules are equally as instructive for those who like to contemplate the war between our inner and outer natures).

I hope you don’t mind somebody mentioning something of the human side of economics on your blog? I don’t believe we need be anything more than human, or understand anything more than what it means to be human, to know what is happening in macroeconomics, politics and commerce today on our absolutely unique little planet, can be described both as potential for far reaching good and far reaching stupidity, in some cases evil – and we need look no further than ourselves for a cause, nor explain it in any other terms than ourselves as the reason (no blaming the Gods or the Devas, or the poor apes who provided us a vehicle of motion – I wonder if they look at us and are disappointed?). As William Glasser M.D. is fond of pointing out – Life brings us choices and consequences!

I am glad there is a thread in this world that passes through the macroeconomic swamp. My feeling is that for all the apparent good fortune of the insurance industry in the US, if I have understood correctly what happened in the wake of the Great Depression when government hit a wall, that bloody (sacrificial) bull should watch out!

Regards,

jrbarch.

Jbarch: your beautiful, incredibly insightful comment made my heart soar, something I need to connect to daily as the fear spins out of control here in the States. Thank you for reminding me that no one can ever take away my humanity.

And Professor Mitchell: I have never formally studied economics beyond my introductory courses in college, but I have tried hard in the past few years to make up for lost time. I want you to know that you have an incredibly grateful reader here in Chicago in the U.S. who is urging you on each day. May the force continue to be with you!

Perhaps a technicality, but Ferguson also seems to mis-apply the Biblical metaphor “like a thief in the night” to mean ‘suddenly’.

Unfortunately, just the presence of this phrase probably subliminally increases the appeal of his article to many of his admirers and readers who dont follow MMT.

Resp,

Fergson is a historian rather than an economist, and as a historian he is a wanker. He should know that historians have enough trouble getting the facts straight based on evidence, let alone causality. And historians look at history – the past – not the future. History says nothing about the future other than in the most general sense. (Actually Ferguson admits this in his counterfactual theory.) Of course, Western civilization will decline, just as have all other civilization, but when and how no one is able to predict other than by chance. If there are enough predictions out there, someone will turn out to be correct, but that proves nothing.

Ferguson is just promoting himself, and the press is too dim to see that, or too anxious to stoke the fire in order to promote its own interest. Other historians have criticized him as having abandoned scholarship for a grandstanding. Krugman and DeLong have eviscerated both this economics and his economic history. Why do people still pay attention to him?

Jrbarch, nice to see some humanism applied to econ. Mainstream economics is based on utility, which is a modern version of classical hedonism. The modern version was popularized through Jeremy Bentham as utilitarianism. It was first expressed in the West by Aristippus of Cyrene, a student of Socrates, although its best known exponent is Epicurus. Hedonism/Utilitarianism is based on preference for pleasure and aversion of pain. Aristotle criticized it in the Nichomachean Ethics as erroneously equating happiness (eudaimonia) with pleasure (hedone), when pleasure is of the body and happiness pertains to the whole person. Therefore, pleasure is only an aspect of happiness and a relatively insignificant one for axiology. For example, those who act primarily to gain pleasure and avoid pain are preferring passion to reason, and they are universally deprecated as shallow, venal, or cowardly. Most of ancient Greek thinking was based on rationality as the expression of cosmic order, and hedonism never gained much philosophical footing. It came to be thought of as a philosophy for the base and vulgar rather than one suitable for the noble and best. Hedonism was also condemned in Jewish, Christian, Islamic, and Oriental religion and thought as against divine or cosmic law, therefore, unsuitable for all.

The utilitarian view was further promoted in the modern West by the stimulus-response view of behavioral psychology, which saw human beings as more complex animals but essentially animals nonetheless. This rather primitive view of psychology has recently been increasingly replaced by cognitive science, which recognizes the complexity of human dynamics based on brain functioning and shows that a stimulus-response model of human nature is simplistic.

The neoliberal view of economics based on self-interest as utility maximization is at odds with both humanistic and religious thought of Western civilization, including the way this thinking has been institutionalized, e.g., in ethics and law. it is also putting the Western neoliberal-domnated policy at odds with China, as Henry C. K. Liu observes here.

I’m still trying to wrap my head around MMT. Its simplicity is too uncomplicated for my mind to grasp with ease given my formal education in Finance. Unlearning is difficult.

I have some sympathy for the end of the world types, especially from a historical perspective. True, the world has already changed. Several decades of neo-liberal economics have seen to that. I have the vague feeling that the MOTUs (masters of the universe) in the West have looked at the economic-political landscape of the near future and are very apprehensive about the rise of competion from the BRICs. For the past decade these MOTUs have had a virtual field day directing all of society’s revenue streams into ever fewer hands with no pesky interference from outside competition. They just hustle for a sliver of the wage contraction and privitisation schemes. Real work scares them silly.

Maybe my perspective is coloured by my so called nation of residence – Ireland. Such terms as the “knowledge economy” and so on are nothing more than code for the elect to perserve to the detriment of common wage earners; where a few initials after one’s name, however deserved or obtained, count for more than accomplishement. I also take these apocalyptic stories or essays as a way of conditioning the peons for a poorer future so that the MOTUs can live in a style to which they’ve become accustomed.

I’ll still continue to try and comprehend MMT but, even at my advanced years, will become more hippy-like and opt out of the rat race. De rats always win.

Bill,

If there is a continual misunderstanding about what you termed the basic precept of MMT–namely that sovereign governments can issue all the money they please, why does MMT persist in using the term “debt?” If it doesn’t look like a duck, and it doesn’t quack like a duck, nor does it waddle like a duck, why keep calling it a duck? And for that matter, why keep calling spending “spending,” when it really isn’t spending, and when the term sets off a serios of false associations that are very difficult to counter. It just makes the mental difficulty of adjusting to a new perspective all the more difficult. Would it not be better to jettison such terminology? The difficulty is compounded when one has to shift from the vantage point of a federal entity with sovereign powers, to that of states in the US or of the EU, where the “old” terminology is more applicable–but unnecessary, given the powers of the sovereign issuer, who could easily remedy “debt” and “deficit spending” difficulties.

Such terms as the “knowledge economy” and so on are nothing more than code for the elect to perserve to the detriment of common wage earners; where a few initials after one’s name, however deserved or obtained, count for more than accomplishement.

I don’t think that’s necessarily the case. In fact, the transition to a knowledge society with an information economy may be much more amenable to alternatives than the more structured industrial society. It doesn’t mean that everyone will be a knowledge worker, either, or that all knowledge workers will be very highly educated in terms of academics.

Digital artists and musicians are considered knowledge workers for example, and the industries that provide employment to such people are now huge. Through digital distribution this is becoming decentralized. So I see this this a positive step forward that will reduce the number of “factory rats” as automation and robotics replace manual labor. Most kids growing up in a digital environment are accomplished knowledge workers just through the skills they acquire through play – which is as it should be.

There is a broad literature discussing this swiftly unfolding trend. For example, see Knowledge Society, Information Society, Information Economy, and Knowledge Economy.

This is not a new idea. Economist Fritz Machlup began working on the idea in the 30’s, and published The production and distribution of knowledge in the United States in 1962. Historians estimate that the transition to a knowledge or information society began in the 70’s. No one knows quite what this is going to look like, however. But I would say it is going to be a shift on the order of that from chiefly agriculture to industry. Post-industrial society is going to be very different culturally as well as economically, if only because the concept of work is going to change radically.

Dear Tom,

If you want to read another approach to knowledge as capital, formed under conditions of anomaly, I can e-mail you a paper I wrote a few years ago.

Regarding utility and rational theory, Greek philosophers incorporated both in their analyses including the rule of law. Utility is the criterion of operation consisting of security in construction of entity and of value in estimation of identity. Reason is the criterion of behavior consisting of rationality in decision of subject and of law (rule) in praxis of object.

More Treasury data is known than that starting in 1964.

http://www.ifs.org.uk/bns/bn26.pdf

The U.K. had a tight fiscal stance from 1950-1970, with budget deficits around 2% of GDP.

From 1970-1990:

Of course, this paper was written in 2002 🙂 — little did they know that this pattern would continue.

In general, it is the taxation policy that matters here, not the fiscal deficits.

highly progressive taxes = low and stable budget deficits, moderated business cycle, low employment

less progressive taxes == highly cyclical (and rising) budget deficits, highly cyclical unemployment levels, strong correlation between deficit spending and employment.

Which makes sense.

The degree to which unemployment and output is correlated with government deficits over the business cycle is a measure of the sickness of the private sector. A sector that is so out of balance as to not be able to deliver living wages will require a constant stream of government deficit spending to avoid mass output contraction. A private sector that is balanced and pays its worker enough to purchase output will not require massive stimulus spending.

The more inequality rises, the more $ you need to spend in order to get a stimulative effect, and the more inequality rises as a result of the stimulus. You get large cyclical variations in which the peak keeps increasing along with the increase in inequality. That is the unsustainable cycle to be worried about, rather than total debt or deficit spending, per se.

bass-ackwards! 🙂 Over the business cycle, the government can control deficits via taxation policy, and cannot control yields. Over the very short run, it can control neither. I would focus on what the government can control — progressive taxation and spending, so that unemployment is not correlated with deficit spending over the business cycle, rather than pretending that growing inequality is some God-given thing beyond our control. And I would focus on those issues, rather than instructing the BoE to make the weather nice and yields low.

Bill: We also know that the private domestic sector in the UK has been on a debt binge over the last decade which fed a huge real estate boom. That sector is now deleveraging (too slowly but it is) and is being supported by the public deficits.

Couldnt the same be written about Australia? except: instead of deleveraging we are being bombarded in the press that we will miss the real estate boom if we dont releverage NOW. This is either the final phase before a Minsky Moment or its a pie in the face for anyone who has based their investments on actual study.

Thanks to jrbarch for reminding us to look inside first. People Places and Things cant make me happy, looking inside can.

Try to keep your posts real as not all readers are boffins. Cheers Punchy

The relationship between unemployment and public deficit with a positive slope is more important than the relationship between unemployment and inflation. Discretionary public spending (public investment) should target the unemployment/underemployment rate, given the automatic stabilizers. Additionaly, this will have a positive impression effect (expectations) upon households which will accelerate the recovery of employment and GDP and reduce the deficit. Then, discretionary fiscal policy becomes endogenous responding to employment trends.

Thoughts on Crisis.

Extreme reaction/reality (tails) or a crisis consists of the following terms.

1. Excessive behavior or motivation, bounded recovery from inertia, bounded impression from illusion and accidents/infections that calibrate the reaction rate.

2. These bring extreme surprise.

3. Extreme surprise brings exclusive behavior and operational shortfall.

4. These bring feedback loops that lead to unstable spirals.

4. The result is the reality of extreme reaction or crisis.

These terms of reality cannot be counterbalanced if penalty policy of taxation against excessive behavior and inclusive policy of public spending against the other terms, are restrained by either voluntary (private interest pressure) and/or involuntary (charter) induced tax revenue and public finance constraints. The capitalist system/charecter is unstable as struggle from private interests with legislation, political influence and market discipline, defeats public policy. This struggle process cannot be excluded for the analysis to be complete and realize the unstable path to crisis. Crisis can then bring forward a regime switch or revolution depending on the circumstances.

RSJ: “The more inequality rises, the more $ you need to spend in order to get a stimulative effect, and the more inequality rises as a result of the stimulus.”

Doesn’t that depend upon how you stimulate? If you put money in the hands of the poor, who will spend it, doesn’t that give you an efficient stimulus and, to some extent, reduce inequality?

Α shift in public deficit spending has horizontal structural effects upon the total porrtfolio balance of the economy.

1. The composition of resources/productive capacity shifts towards the public sector and away from the private sector.

2. The composition of equity in the portfolio balance shifts towards reserves and currency.

3. The composition of debt shifts towards public debt as the private sector deleverages.

4. The average interest rate in the economy is reduced as public debt has less risk than private debt.

5. The spread between the target interest rate of the central bank and the average interest rate declines.

6. Eventually, this means that the capitalization rate of private investment is reduced and the spread between the price of capital and the price of investment increases, so private investment becomes more attractive and shifts upwards.

Min,

“Doesn’t that depend upon how you stimulate? If you put money in the hands of the poor, who will spend it, doesn’t that give you an efficient stimulus and, to some extent, reduce inequality?”

If by “reducing inequality”, you mean the distribution of financial assets, then no. If by “reducing inequality”, you mean “reducing the inequality of goods consumed”, then yes.

The reason is that asset flows move in the opposite direction of goods flows. So if you give $1 to the poor, who save 5% of that and spend the other $0.95, then although you are improving the consumption of the poor by $.95, the bulk of the increase in financial assets will accrue to the rest of the households in proportion to their existing financial asset shares.

From the “money illusion” point of view, as long as consumption inequality is reduced, you don’t care. But if you believe that an economy is a delicate balance of prices, then you don’t want to separate the relationship between wages and prices, as it will lead to economic stagnation and fragility. A perfect example is the auto Industry. The weighted average cost of new cars in the U.S. went from about 40% of median incomes in 1980 to over 50% in 2007. The price of cars was outpacing the growth of wages, resulting in increasing debt burdens. And when households retrenched, the cost of cars went back to 40% of wages during this recession. Manufacturers discovered that there was no demand for the more expensive, larger cars — but these were long term investments with huge supply chains and decades of R&D. All devoted to building products that people did not want to buy.

As a result, large swathes of those capital investments are worthless, and smart hard-working engineers are being fired because management was acting on false price signals. It’s very dangerous to let prices get out of line with wages.

I am a strong believer in political interference, but designed to keep wages in line with prices — i.e. counter-cyclical interference.

To be clear, this is not to say that we should not have social spending, but spending is not the same as deficit spending. A Job Guarantee, health care, pensions, free education — all of that refers to spending, and need not refer to deficit spending.

In fact, to the degree that those who receive a net benefit from the economy by accumulating financial assets have a responsibility for keeping the economy healthy, then you can argue that deficit spending gives them a free pass and allows the growth of their assets to become disconnected from the growth of the underlying wages.

Moreover, you can always stimulate demand by boosting the incomes of those who have a high propensity to consume even while draining back a similar amount from those who have a low propensity to consume. I.e. even an economic stimulus need not require deficit spending.

Of course, a growing economy does require deficit spending in order to avoid deflation. And automatic stabilizers will require more, but the amount of deficit spending required, over the business cycle, is also a measure of wage inequality.

The best example of this is the success of Korea compared to the failure of Japan. One nation has had rising (or relatively constant) median wage shares for the last 30 years, whereas the other has had 35 years of declining median wage shares. One is a growing economy whereas the other is stuck in deflationary hell. Both are industrial powers, but one is a success story of continuous union struggles and internal reforms whereas the other is a story of government income support papering over internal problems, letting them get worse each year.

And as Japan has found out, at some point, median wages fall so much in relation to output that the economy becomes completely dependent on deficit spending, and the prices are so politicized that capital investment is politicized as well.

So there are downside inequality risks and growth risks to spending without draining back, and it would be good to hear what the MMT views are on mitigating these risks.

A few points to make –

1: Ferguson argues in the logic and style historians are taught. I know, I have a degree in history. I also found it irritatingly illogical at times because it is rhetorical to pose such causal links and implies a post hoc model of factors that lead to collapse. Perhaps it was Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire that permitted that idea to enter the logic of history studies.

2: Hartcher is idle if he wants readers to see his edits of another persons work No wonder we are all giving up on the mainstream media.

3: Reading Bill’s frequent fulminations against the nonsense of the major media it seems that the notion of veracity and accuracy in an empirical sense is irrelvant with economics and economics commentary. Economists disagree about things that can be called basic facts. Economic commentators such as Lawson – son of Nigel, brother of Nigella – dispense their analysis based on inaccuracies. Rather than being mocked for their foolishness, their analyis is heard and even adapted into policy. That means the economic argument/analysis is a discourse or a complex ‘meaning game’. It is an idea Wittgenstein, or even, (shock horror) one of those deconstructionists would comprehend.

4: Because economics is so intimate with political positions/ideology, perhaps only a sufficiently damaging and enduring crisis will shake up economics and the commentators. Shake the shamans out of the so-called profession.

I see Crispin Hull has also just read Ferguson and gotten himself excited.