These notes will serve as part of a briefing document that I will send off…

Inflation is coming, well, it could be, or, it might happen, gosh …

One could make a pastime observing the way that so-called ‘expert’ commentators change their commentary as the data unfolds. As one rather lurid prediction fails, their narrative shifts to the next. We have seen this tendency for decades when we consider the way mainstream economists have dealt with Japan. The words shift from those implying immediacy (for example, of insolvency), to those such as ‘could’, ‘might’, ‘perhaps’, ‘under certain conditions’ and more. The topics shift. The commentariat were obsessed with ‘this time is different’ during the GFC and the ‘debt insolvency threshold’ rubbish that the likes of Reinhardt and Rogoff propagated. That is, until they were sprung for spreadsheet incompetence. More recently, we have apparently forgotten how many governments were about to go broke and the mania has shifted to inflation. The data shows some price spikes earlier in the year which set of the dogs. Now, things might be shifting again. It is a pastime following all this. Short memories, no shame is the only requirement that is required to be a mainstream economics commentator. Prescient knowledge is not included in that skill set.

On April 15, 2021, a Project Syndicate Op Ed, republished in the UK Guardian – Why stagflation is a growing threat to the global economy – saw Nouriel Roubini jumping on the inflation mania, which was all the rage around 3-6 months ago.

The causality seemed to be this:

1. National statisticians publish data showing that the CPI was rising a bit.

2. Eek, must be a return to the 1970s inflation.

Pretty simple really.

Roubini thought in April that accelerating inflation was coming because:

1. “the US has enacted excessive fiscal stimulus for an economy that already appears to be recovering faster than expected.”

So this is what we call a “demand-pull” motivation – where aggregate spending outstrips productive capacity and firms use market power to push prices up.

2. ” the bulge of private savings brought by the stimulus implies that there will be some inflationary release of pent-up demand.”

Another demand-pull motivation, where households will go on a spending binge because they haven’t been able to spend much during the various lockdowns.

3. The QE programs run by the US Federal Reserve “will drive inflationary credit growth and real spending as economic reopening and recovery accelerate.”

So apparently Roubini thinks that banks loan out reserves.

I don’t know of one country where the banks use the funds in accounts with the central bank that are designed to facilitate the integrity of the payments system (making sure ‘cheques clear’) to make loans to retail customers.

4. “Centrals banks have been monetising large fiscal deficits in what amounts to “helicopter money”, or an application of Modern Monetary Theory.”

Roubini clearly has not comprehended what Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) is.

Even if the central bank had bought zero government bonds, the monetary systems would still be demonstrating the principles of MMT.

MMT is not defined by central banks buying government bonds.

But his point is that because central banks have bought so much government debt, if they tried to sell that again – a process he refers to “Monetary-policy normalisation” (whatever that is) – then bond prices would fall dramatically and credit markets would collapse and there would be “a recession”.

Apparently, this means that “Central banks have effectively lost their independence”.

Of course, they never were independent – that is just a myth propagated by the mainstream to allow governments to depoliticise macroeconomic policy settings by appealing to the volition of technocrats rather than politicians.

Central banks and treasuries cannot be independent because the impacts of fiscal policy have daily implications for the core liquidity management functions of the central bank such that close coordination is always required for both fiscal and monetary policy to be effective.

But there is no reason for central banks to sell off their debt holdings.

The debt will mature and the government will just make some accounting adjustments between the treasury and the central bank and no-one will be any the wiser.

5. Roubini then moved onto the 1970s scare, which is becoming common among commentators.

He wrote:

The problem today is that we are recovering from a negative aggregate supply shock. As such, overly loose monetary and fiscal policies could indeed lead to inflation or, worse, stagflation (high inflation alongside a recession). After all, the stagflation of the 1970s came after two negative oil-supply shocks following the 1973 Yom Kippur War and the 1979 Iranian Revolution.

So back to the 1970s.

We need to be careful here.

The 1970s inflationary episode did begin with the OPEC oil price hikes, which increased imported raw material costs for oil dependent nations and those nations, such as Australia, that foolishly prices its own produced oil on an import parity basis (as a sop to big multinational oil companies who make threats they will stop drilling unless they get super profits).

But that supply shock alone was not sufficient to drive the accelerating inflation that followed and was not fully extinguished until the deep recession in the early 1990s.

What happened next was crucial.

The inflation of the 1970s which persisted into the 1980s was not because there was excessive nominal demand coming up against finite productive capacity.

Rather it reflected the ‘battle of the markups’ as bosses and unions slugged it out (in the ‘distributional’ arena) as to who was going to bear the real income losses associated with the OPEC oil price hikes that cut national incomes for the nation as a whole.

Inflation resulted because workers pushed for nominal wage rises (so-called ‘real wage resistance’) and firms responded by pushing up prices (so-called ‘margin resistance’).

The causality work in the opposite direction – I do not suggest here that the trade unions began the process.

This blog post provides more detailed background reading – Distributional conflict and inflation – Britain in the early 1970s (April 7, 2016).

The question then is whether this sort of wage-price or price-wage spiral could respond to the current supply chain cost shocks to perpetuate an accelerating inflation.

My assessment is that there is little prospect of a 1970s-style stagflation because the structural and institutional factors that were crucial to the 1970s episode are no longer relevant.

There was an article in the New York Times (September 18, 2019) – A Rerun From the 1970s? This Economic Episode Has Different Risks – that reflected on these issues.

The article considered the spike in strike action in the US at that time and concluded that:

… there are big underlying differences between the early 1970s and now. Understanding those differences is important in properly understanding the world economy in 2019 and the risks posed by this combination of events.

It noted that:

The early 1970s was also a period of labor strife … That was an era of rapid inflation, and labor unions were at the height of their power – two phenomena that were connected. The G.M. workers demanded pay increases that would outpace the already high rate of inflation, and with the strike, they got it …

Autoworkers and other powerful unions in that era fueled higher inflation economywide by demanding – and getting – ever-escalating pay increases, which fed into consumer prices …

That’s not what is happening in 2019. It’s not just that union membership has fallen to 10.5 percent of the work force in 2018 from about 25 percent in the early 1970s.

And, importantly, the “autoworkers striking today are essentially trying to claw back some of the compensation they have lost over a brutal decade.”

In most nations, the bias towards austerity and the persistence of elevated levels of unemployment have led to a widening and large gap between productivity growth and real wages growth.

That gap, representing a major shift of national income distribution to profits, means there is substantial non-inflationary room for real wage increases.

The decline of trade unions as a powerful counterveilling force in our communities is a global phenomenon.

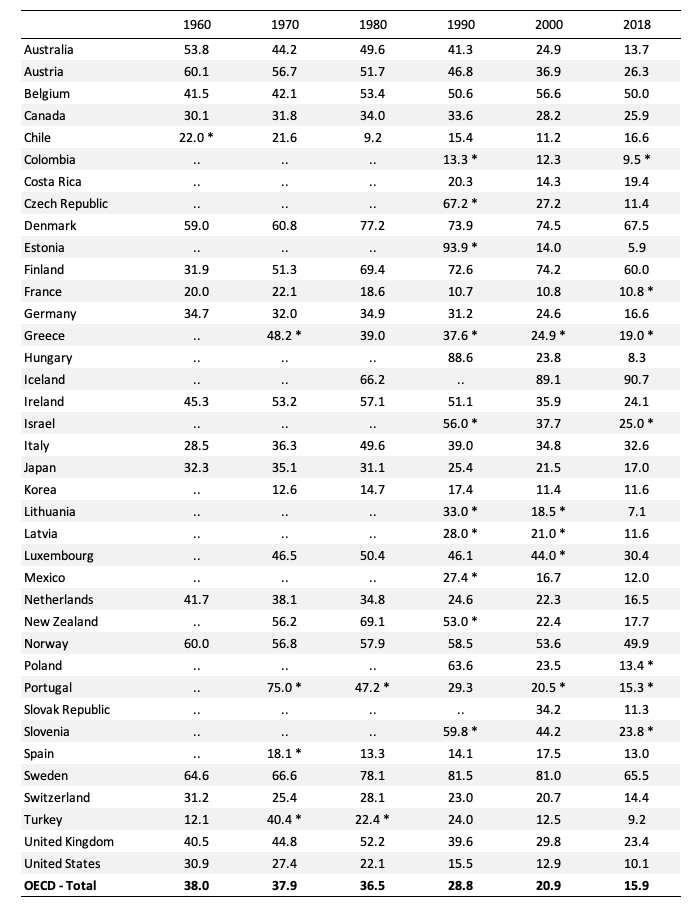

The following table is taken from the OECD trade union coverage database and shows the evolution of coverage from 1960 to 2018. The entries are aligned at the beginning of each decade although the * entries are for situations where the data is not continuous for the entire period. In those cases, the data is the highest value in the relevant decade.

The trends are obvious.

In Australia’s case, for example, the coverage of the unions has shrunk from 54 per cent in the 1960s to just over 13 per cent now.

And much of the loss of coverage has come from the private sector as the decline of the manufacturing sector and the rise of the services sector has made it much harder for unions to organise.

Legislative shifts have also undermined the capacity of unions to engage in industrial action in defence of their members’ wages and conditions.

OECD Trade Union Coverage Rates, 1960 to 2018, per cent of total workforce

The question then is how are workers going to prosecute declining real wages in the event of a supply side shock that firms pass on in the form of higher prices?

The answer is that they have only limited capacity and that capacity is not sufficient to drive a major 1970s style inflation.

It is possible that the increased concentration of industry, which means that firms have greater market power now than in the 1970s, could drive a continuous rise in prices.

But that would be easily dealt with via anti-competitive industrial regulation.

After all that, it seems that Nouriel Roubini has moved on a bit.

His latest Op Ed in the UK Guardian (August 3, 2021) – Biden has a better handle on economics than Trump – but there are still risks – is now more muted.

The article suggests that Biden is really more like Trump than he like Obama and Clinton.

Biden has continued the “sharp break from the neoliberal creed followed by every president from Bill Clinton to Obama.”

Biden and Trump both have deployed “nationalist, inward-oriented trade policies” in contradistinction to the ‘free trade mania’ of their predecessors.

Both have been comfortable with the Federal Reserve Bank funding “large budget deficits”.

Both use “large direct transfers and lower taxes for workers, the unemployed, the partially employed and those left behind.”

And then as an aside, Roubini remembers that a few months ago (cited article above) he was preaching a major inflation outbreak.

So he concludes by briefly rehearsing the “risks” of the maintenance of this policy approach.

And the nuance is in the words:

Loose fiscal and monetary policies may help to increase labour’s share of income for now. But, over time, the same factors could trigger higher inflation or even stagflation (if those sharp negative supply shocks emerge) …

Could.

Which means the commentator has no real idea.

Conclusion

Could (pigs) might fly.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2021 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Bill,

The decline in union membership in Germany was/is directly related with the fact that they were PRO Hartz 4.

What will probably happen when the rampant high inflation does not materialise is the narrative will switch. Rather than admit they have no idea what they are talking about they will then switch their commentary to asset price inflation.

House prices have been inflated and Stock markets have been inflated and this is where the inflation ended up due to MMT zero rate policy. That is what they did after QE and that is what they did after 2008.

So when talking about inflation We should talk about asset price inflation more. Because if I am right then this is how their narrative will change rather than admit that they were wrong. It is just rinse and repeat with these guys.

Has housing and stocks for example attracted funds because of the zero rates or are they backed up by fundamentals. Will asset price inflation increase inequality and the difference between capital goods and consumption goods etc, etc, etc….

Is all worth highlighting as we have all been here before. As the narrative coming down the track will be, we didn’t mean that type of inflation We meant the other type of inflation.

So I am happy you don’t think inflation will become a major problem but unhappy about your reasons why. Workers losing bargaining power over their wages is not a good thing in my book. Even if it means inflation will be subdued.

Why can’t it be that higher wages force firms to invest in better management techniques and the most advanced technologies in order to get the most out of their higher cost labor? Or is that just wishful thinking on my part? How is it that real wages can increase without causing inflation or, as in my most hated Weekend Quiz question ever, somehow causing ‘mass unemployment’? I still dispute the latter as a reasonable cause of mass unemployment despite your answers on the quiz, just in case you were wondering about that.

Well anyways, I doubt Larry Summers could fly even if he was assisted by a flying pig and flapped his arms about frantically. Maybe if they were both on a large airplane.

“So when talking about inflation We should talk about asset price inflation more.”

We should talk about artificial asset price suppression.

Interest rate setting is an artificial market intervention that attempts to suppress asset prices. The current price of assets is actually their ‘natural’ price without governments subsidising banks.

“Why can’t it be that higher wages force firms to invest in better management techniques and the most advanced technologies in order to get the most out of their higher cost labor?”

That’s known as the paradox of productivity. Productivity improvements just lead to falling prices, so firms try to avoid doing productivity improvements and prefer to try and obtain monopoly power instead. That’s what a ‘market niche’ is.

Higher wages will lead to some firms failing, which releases people onto the labour market, driving down wages. If you try to hold those jobs up, and force losses onto the other side you end up with an investment strike and the whole house of cards collapses into stagflation.

Failing to match higher wages with higher product *must* result in *both* investment capital and the demanding wage earners taking a cold bath. Pour encourager des autres.

The economic system is a referee. It must not favour either side in the football match.

Per MMT as I understand it- the economy is a human construct that can and should be used to advance human welfare. The economy should serve people rather than people serving the economy.

I appreciate the answer Neil. But in some ways it assumes that the optimal distribution between labor and capitol has been reached and is always in effect. Which is as realistic as assuming the economy is always at full capacity.

And why would firms in a competitive capitalistic system ever try to avoid productivity improvements? I mean I could understand them not wanting to share the benefits of productivity increases with their workers- but hey- they increase profits until they might have to share a bit.

Push wages up leads to pushing firms to increase productivity. Why not? Implement a Job Guarantee with a living wage as Bill describes it- that is what it will do for millions of the lowest paid workers in my country. And what it will do to their present employers. And I’m all for that.

Real wage increases have been lagging so much in relation to productivity growth over the past almost half a century that even if there would be a substantial increase in labor remuneration, it shouldn’t be a sign of alarm for escalating inflation. Instead, as I see it, it would help restore labor’s share in the distribution of income to it’s long term trend. The capitalist class, after all, must accept that keeping real wage rise in line with productivity gain is to their own benefit as well.

Artificial asset price suppression.

Yeah, all of it Neil. The whole shebang. Cause it is coming down the track on a TV near you rinse and repeat.

Since 2008 and QE which they think is a MMT policy choice along with helicopter drops and cranking up the printing press. Some have never stopped talking about it. MMT inflates assets.

We’ve won the inflation debate in Bills piece. Time to break down the other side into little pieces and win that debate within the mainstream media also. We are never going to win it on seeking alpha but have to win it on mainstream TV.

The election of the Thatcher government in 1979 is usually described as representing a move to the right by British society but that is an over-simplification that doesn’t really help us understand the actual dynamics of what Thatcher represented. It also avoids the culpability of the labour movement in creating the conditions in which someone like Thatcher could thrive. A more accurate description would be that she represented the reaction of the electorate to the political and economic future that the labour movement had threatened to create through its irresponsible behaviour in the 1970s. At that time the trade union movement had shown by its actions that it was in control of most aspects of civil society from the disposal of the dead to the people’s access to energy and light. The question that dominated the concerns of civil society was how that power was to be used in the future. Up to then that power had been seen to assert itself as a disruptive power used in a sectional interest. What remained to be seen was whether it could be used responsibly by putting it to a more constructive use in the wider society.

In many ways the answer was given in the rejection of the 1977 Bullock Report on industrial democracy. That rejection came about through the dominant influence of a narrow sectional mindset among most of the trade union leadership and an ideologically constrained left-wing in politics. Those in the leadership of Labour politics who saw the problem in clear electoral terms, being unable to bring these elements into line, were then deemed to be an ineffective element in an evolving situation that could not be sustained indefinitely. The electorate was confronted with a Labour leadership that was unable to influence the way in which the enormous power of the trade union movement was being used. Consequently, the Labour Party was seen to offer no alternative to the ongoing prospect of continued industrial strife and anarchy.

“And why would firms in a competitive capitalistic system ever try to avoid productivity improvements?”

Compare the cost of a concert violinist to a loaf of bread in the 19th century vs today. That’s what productivity increases do over time – because it takes less human time to produce an item, and time is really what everything ends up being priced in.

That’s the paradox of productivity. Productivity improvements ultimately leads to cheaper prices not increased profits. Because that’s what competition is there to do. The profits can go further – in that they can buy more stuff. But capitalists like to accumulate units of account.

In essence the dynamics of pure competition leads to an oversupply in the market which brings prices down until firms start to go bust to eliminate the oversupply. Therefore market players try to stop competition happening by constantly seeking a monopoly perch on which to extract rent.

The myths of free market beliefs say it all sorts itself out. It doesn’t. The system has to force competition onto essentially reluctant players, and eliminating the clarion call of “what about the jobs” is one way of doing that – let bad firms go bust.

All this talk of national debt, governments becoming insolvent, massive inflation and the rest appears to be a form of gaslighting the public…..

gaslighting

manipulate (someone) by psychological means into doubting their own sanity.

The only asset which matters is land – in particular potential residential land. MMT ignores the theory of rent (Ricardo’s sole contribution to economics).

I don’t know Neil. A company that can produce more with the same inputs (costs) is going to do that if there is a market for their product. A firm that can produce the same as last year but with less inputs is also going to do that. Because at least for a while, they will make more profit. Theoretically their competition will eventually learn how to do the same and the excess profit will disappear. But it is there for a time so why not grab it if you can.

I never hired a violinist of any age and have not purchased any 19th century bread either, but I suppose you are saying that someone could buy a whole lot more bread now for the price of hiring a violinist than they could in the 1800’s. That may be true but it doesn’t have much to do about what I said as far as I can tell.

“A company that can produce more with the same inputs (costs) is going to do that if there is a market for their product.”

That’s the problem, there isn’t. Because the costs is the income that is used to buy the product (in aggregate).

If you expand output then you are selling to the same income which implies the price must go down to shift the increased amount of stuff.

“Theoretically their competition will eventually learn how to do the same and the excess profit will disappear.”

Not theoretically. That is exactly what happens. The dynamics of market share maintenance then kick in and prices go down. You get a short uplift and then a nosedive. When you’ve been in business long enough you know that getting into a niche is better than constantly trying to run up the down escalator.

“That may be true but it doesn’t have much to do about what I said as far as I can tell.”

It has everything to do with it. Because items are ultimately priced in person time used to create them.

We all make plans but when it boils down to it actual demand must match actual supply at the point of effective demand – whatever the plans were.

I think you are switching from micro to macro economics at the wrong points Neil. An individual firm has an incentive to produce more at lower cost unless it is the monopoly supplier in that market. Even if it is, it still has an incentive to lower its costs unless it is some military contractor being paid on a cost plus basis.

Following what you say there would be no improvements either in productivity or in products. Because what would be the point of improving things if you aren’t going to benefit from them at all. But it is obvious that many products are both far better and less costly in real resources to make than in the past.

If labor costs more it will push firms to use labor saving techniques- that was what I asked originally. Increase productivity in other words. Alternatively, they could go out of business altogether I guess. I don’t think you disagree with that- but maybe I’m wrong.

“I think you are switching from micro to macro economics at the wrong points Neil.”

I’m sure you do, but since I’ve done a lot of this for a living I’m quite comfortable with how it works in practice in the real world.

“Following what you say there would be no improvements either in productivity or in products.”

That would be a straw man attack, and would suggest you haven’t understood what I’m saying. So we’ll leave it there.

Okay. But you should realize that I was not attacking you. With strawmen or anything else. Just trying to have a discussion. It is entirely possible I haven’t understood what you have been saying. It is also possible that I have expressed my thoughts poorly in my comments and questions about this.

Behind Jerry’s comments, it seems to me, is the sole reason that MMT matters. What the lens shows us is that the economy is but a human construction, one which can be arranged and operated to serve the interests of the few or the welfare of all, to promote planetary health or engender ecocide. What is the purpose of MMT, who cares about the clarity of its lens, if it merely gives us a sharper, more magnified view of unfolding human or environmental disaster? It’s when Bill talks about his meta-economic values, which inform but do not originate in economics, that his voice rises from the academic level to the prophetic…and suddenly people like me (and presumably Jerry) are all ears.

Neil,

“If you expand output then you are selling to the same income which implies the price must go down to shift the increased amount of stuff.”

If macro output expands, macro income expands.

What happens to prices is moot.

With all due respect, Prof. Bill Mitchell does not appear to fully understand what is happening, in my opinion. Yes, MMT is a good “description of prescription” but is it any more than that? That will be my point one. My point two is that Prof. Mitchell does not appear to give adequate analytical weight to secular stagnation and asset inflation. These have strong implications for crucial issues from ecological sustainability to increasing wealth inequality.

What do I mean by “description of prescription”? MMT is a formal-system descriptive theory meaning it describes a prescribed formal system. We might contrast that with a real system descriptive theory describing a real system, like the Laws of Thermodynamics describing the thermodynamics of real systems. This has important implications which I will get to.

MMT describes extant money operations and exposes formal truths (like accounting identities) about extant government and banking money operations. The extant money operations themselves are “prescribed”. That is some humans, the elites basically, prescribe these money operations. MMT is useful in exposing the “smoke and mirrors” aspects of this prescribed system. MMT is useful in overcoming the obfuscation and mystification employed by orthodox pro-business or pro-capitalist economists and politicians to convince us money can only be used in their prescribed ways. MMT is useful in overcoming the strong tendency in pro-capitalist economics to reify money as real and current prescribed money operations as the only way money can be used: essentially to funnel all wealth upwards to the super wealthy were it accumulates (at least in formal accounting) in a potentially endless manner.

MMT can be characterized as a descriptive theory of a prescriptive formal theory useful (in this case) for re-jigging the prescriptions of the formal theory for better real outcome. In plain language, this means we can in theory and with theory replace bad rules with good rules. This brings in axiology, the philosophical study of value.

Here, I refer to moral philosophy, not to conventional economic’s (classical or neoclassical) “theory of value”, via utility theory as “utils” or as micro-applied RDEU (Rank-dependent Expected Utility) which theory is completely spurious. Some aspects of RDEU may well be valid when employed for macro public policy decisions related to macro probabilities for expected utility and dis-utility or risks. For the refutation of classical/neoclassical “utils value theory” and Marxist SNALTs (Socially Necessary Abstract Labor Time) I refer people to “Capital as Power” by Shimshon Bichler and Jonathan Nitzan, fully available online free as a PDF manuscript.

Changing bad rules for good rules involves and must involve moral philosophy and real systems science as the hard sciences of physics, chemistry, biology and ecology. It cannot involve, in the first instance, mere prescriptive economics whether the prescriptions are for private property and markets (in some form) and/or for money operations of any given kind. What I am saying here is that moral philosophy and hard science must come first. Moral philosophy determinations must be made from a deontological or consequentialist perspective. To quote Wilipedia,

“In moral philosophy, deontological ethics or deontology is the normative ethical theory that the morality of an action should be based on whether that action itself is right or wrong under a series of rules, rather than based on the consequences of the action.”

“Consequentialism is a class of normative, teleological ethical theories that holds that the consequences of one’s conduct are the ultimate basis for any judgment about the rightness or wrongness of that conduct. Thus, from a consequentialist standpoint, a morally right act (or omission from acting) is one that will produce a good outcome.”

De-ontological ethics are aptly named in my view. They have nothing to do with the ontology of the real nor the relative in the real (all real systems are fully relational). De-ontological ethics have only to do with the legalism of absolute assumptions and claims about truth and ethics. Consequentialism, in contrast, while inescapably incorporating some normative ethical theory by initially supposing some a prioris as axioms (unavoidable in moral philosophy and indeed all philosophy) still refers to the real, still has a real ontological aspect in its process of application and continues by all of dialectical, feed-back and empirical manners to check real outcomes, including unforeseen consequences against the initial axiomatic normative ethic being applied and thence potentially modify or replace the ethic involved based on real feedback and the further human moral and axiological response to the feedback. When new empirical facts on the ground are discovered, clarified or emegent, we change our minds.

“When the facts change, I change my mind. What do you do, sir? – attributed to John Maynard Keynes.

To sum up my part one, MMT is “only” a description of a prescription set (modern money operations) but admittedly also it is a description, to some extent, of the real outcomes of the “prescription set” and other real outcomes which should become possible via an alternative prescription or rule set for money operations . I do have to put quotes around the “only” This standing and actuality of MMT is very useful if grasped and applied. However, it appears to have serious real limitations. These limitations in my view seem to lead to its promoters failing to give adequate analytical weight to secular stagnation and asset inflation (as two examples of what is going on currently).

If I engender any interest, including push-back, with this post, I will post my second part. I offer this as constructive debate and an attempt to bring economic ontology to the forefront of the whole economic debate. Conventional and much heterodox economics, have failed in my view to grapple properly with ontology; particularly the ontology of the interaction and the formal and the real or “rules and reality” as we might term it.

Henry, at the risk that someone will think I am stupider than he already thinks I am, and keeping in mind my limited ability to understand things, I think what is being said is that more output does not necessarily lead to more income. And that firms believe this to be so and therefore are hesitant to implement processes that might increase production or lower their costs. At least if you extend the proposition and maybe stick some strawmen in there or something.

I mean, technically, in macro, total expenditure equals total income and you can add up nominal GDP from either as Bill explains every week in the quiz answers. But you could make some argument where actual output expands while total nominal income and expenditure does not. It would be an interesting argument even if it seems unlikely to me. If it did happen, I would have to think prices would be falling for this to occur.

Yes Newton. That is the most important thing Bill taught me. And the tools to explain it to others is also very important. And yes- I am all ears when Bill expands on his meta-economic values 🙂

I can’t pretend to understand what Ikonoclast’s post – “description of prescription”? I thought that MMT was purely a description,

But I agree with the criticism: “Mitchell does not appear to give adequate analytical weight to … asset inflation. These have strong implications for crucial issues from ecological sustainability to increasing wealth inequality.”

Dear Iconoclast (at 2021/08/08 at 11:17 am)

Thanks for the comment.

Your penchant for opaque, post modernist narrative is one thing – but probably made you feel good so that is something I suppose.

But your assertion that “Prof. Bill Mitchell does not appear to fully understand what is happening … Prof. Mitchell does not appear to give adequate analytical weight to secular stagnation and asset inflation”, (a) doesn’t need any of the POMO stuff to render valid; and (b) is invalid, based on the evidential record.

On secular stagnation, this was a fancy term that Larry Summers tried to introduce to make himself appear relevant, when the world has left New Keynesian economics behind. What does it mean? That business innovation has ceased? That there are no further ways to increase productivity? That business investment is drying up? I don’t see the evidence for that. I see capitalism on state life support, in part, because it always has been.

Second, on asset inflation.

Your comment was on a blog post about inflation as conventionally measured via a CPI or producer price index. It was a discussion within that ambit and has meaning and traction accordingly.

To say I thus ignored asset inflation is then a misnomer.

But, which economist to now do you know who has advocated the legislative elimination of almost all of the financial market speculative activities (banning derivatives trading etc)?

Which economist do you know who has pleaded with the national government to build 450,000 houses that would allow low income workers to avoid the inflating private housing market and take pressure of that market?

Which economist do you know who have pleaded with the national government to abandon negative gearing and other tax advantages on multiple housing/apartment purchases?

Which economist do you know who has consistently argued for a wealth tax and a highly progressive tax on high incomes?

My track record over several decades now will tell you that I am one such economist among hardly any that has been arguing for these things because I am keenly aware of asset price inflation and the damage it can do for the economy and its negative impact on income and wealth income.

You don’t need any POMO babble to go back and read what I have written consistently over my career on those things.

best wishes

bill

Bill,

I sincerely apologize. On proper reflection my initial wording was confrontational and disrespectful. I did not take note of your entire body of work. I did however feel that a discussion of inflation needed an explicit reference to asset inflation.

I have posted an “ontological” reply of sorts to a question by Carol Wilcox. It may or may not appear depending on whether you block my comments. That would be your right of course as this is your blog. I hope however that I might continue to blog here, usually relatively rarely as is my habit.

Your reference to pomo (postmodernism) is inaccurate. As my reply to Carol Wilcox might illustrate to you, my ontological analyses are empirically based and science-congruent in an a priori justification or “truth warrant” fashion. They are part of philosophy following the British Empirical and American Pragmatist traditions. I am well within those hard science and social science traditions which clearly exclude postmodernist relativism. Even in moral philosophy I have very little truck with postmodernism and none with deontological ethics.

I know you are interested in and have written about empirically-based ontology, or at least about economic ontology. Perhaps, since I so clumsily and unjustly antagonized you, the pomo accusation came to mind and for that I am at fault too for provoking it. Mea culpa.

From many years of suffering from, and sometimes dealing directly with, arrogant neoliberal capitalists and managerialists as politicians, bosses, managers and yes, even essentially science-denying academics (which does not include you), I as an intelligent layperson, worker and unionist (now retired from work and unions) have become, shall we say hotly antagonistic about and with doctrinaire authority figures wielding power over others: and of those who make claims to speak from authority in almost any manner be it ideological, religious or the non-scientific academic. The title “Professor” itself can be like a red rag to me except for Professors of the hard sciences and a few branches of the social sciences, IFF I generally concur with them. I try to fight my inner indiscriminate adversiral tendency when I am not confronting avowed and obnoxious capitalists, neoliberals and religionists. Sometimes I fail in that regard.

I can answer with my points about inflation, asset inflation and “secular stagnation” (so-called). I will do so soon if I am not blocked. I can also justify my empirically-congruent ontology in detail but your blog is not the appropriate venue. I am an autodidact layperson in matters economic and philosophical. Given the amount of rank drivel taught in modern academia, outside of the hard sciences, the better philosophy and some of the better pockets in the social sciences (where I place you, believe it or not), this may be no bad thing.

I reserve my right as a thinking human and citizen to put forward my views in a forthright manner. Sometimes I overstep the mark and am just plain rude. Sorry. Must do better. We are actually on the same side of the fence but there are details and nuances where I feel, by analysis and deduction, that I disagree with you. But not having read the entire body of your very voluminous work, I may simply be operating with inadequate data and making some erroneous suppositions.

Can we bury the hatchet and debate from time to time? Cheers, and have a good day.

Okay, now on to my substantive (I hope) comments about secular stagnation and inflation.

1. Secular stagnation.

First, I will quote from “Secular Stagnation – Mainstream Versus Marxian Traditions” by Hans G. Despain in the (Marxian) Monthly Review, in order to give us some historical orientation and a basic definition. The entire article is well worth reading, IMHO, but I will quote about a paragraph here.

“Summers shocked economists with his remarks regarding “stagnation” at the IMF Research Conference in November 2013, and he later published these ideas in the Financial Times and Business Economics.

Summers’s remarks and articles were followed by an explosion of debate concerning “secular stagnation”-a term commonly associated with Alvin Hansen’s work from the 1930s to ’50s, and frequently employed in Monthly Review to explain developments in the advanced economies from the 1970s to the early 2000s.2 Secular stagnation can be defined as the tendency to long-term (or secular) stagnation in the private accumulation process of the capitalist economy, manifested in rising unemployment and excess capacity and a slowdown in overall economic growth. It is often referred to simply as “stagnation.” There are numerous theories of secular stagnation but most mainstream theories hearken back to Hansen, who was Keynes’s leading early follower in the United States, and who derived the idea from various suggestions in Keynes’s General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money (1936).” – Despain.

My main views on secular or long-run stagnation are Marxian and ecological, in the sense that I can see long-run stagnation happening in at least the following ways, usually mutually interactive:

(1) Overaccumulation;

(2) Financializtion;

(3) Wage suppression;

(4) The replacement of labor by machinery and automation;

(5) Global labor arbitrage and its concomitant regional de-industrialization; and

(6) Limits to Growth.

I leave people to look up terms like “overaccumulation” and global Labor arbitrage if they wish to.

When I refer to the replacement of labor by machinery and automation I do not by that reference ‘simpliciter’ imply a necessary loss of productive power: quite the contrary in fact. A further increase in productive power is possible along with the implied and extant loss of wages under a neoliberal system deskilling people and rendering them into de-skilled labor or newly unemployed. The loss of wages combined with high production, even overproduction, then imply overaccumulation as reinvested capital would no longer produce returns.

When I refer to Limits to Growth I refer to it occurring as a set of complex earth system disruptions and not to simplistic case by case running out of raw materials and energy sources. To whit, fossil fuels are still abundant and will not be the proximal limiting factor of economic growth and production. The proximal limiting factor, with respect to CO2 emissions and already getting underway is weather disruption and sea level rise plus other issues and all their downstream effects. We could talk explicitly about plastics pollution, endocrine disruptor pollution, sixth mass extinction, ocean death, zoonotic disease pandemics (think COVID-19), soil loss, fresh water depletion, ocean current disruption, methane clathrate “gun” hypothesis and so on. This is not a mere “gish gallop”. These are all serious dangers and most are already underway if only in nascent form but all likely subject to compunding feed-backs.

To continue to talk about economic growth without strict environmental (real biosphere and earth systems) caveats and to fail to talk about the very possible need for a quantitative, if not qualitative, sustainable circular, sustainable economy is to my mind untenable. Whether formally developed MMT “fails” in this regard I leave to others. I do gain a significant impression, incorrectly or not, that MMT does pay attention to this reality but then rather reflexively goes back to talking about growth without the necessary caveats. This criticism may be unwarrented. I leave it to others to correct me if and as necessary.

2. Inflation

Clearly, when we talk of inflation in the economic context we are talking of increases in the price of a service or good (or some aggregated basket) in the numéraire (money). This presupposes that we know what money is and we use it as a term and as supposedly equatable quantities (in the social fictive dimension of value) “correctly” in our deductions and calculations. But money and financial capital are slippery concepts, ontologically, and we are much wont to fool ourselves about them.

In respect of money and financial capital, I follow the ontology of the Capital as Power theorists. I recommend these readings so people understand what I mean.

(A) The monograph “Capital as Power” by Shimshon Bichler and Jonathan Nitzan.

(B) The essay “The Aggregation Problem: Implications for Ecological and Biophysical Economics” by Blair Fix.

(C) The essay “The Autocatalytic Sprawl of Pseudorational Mastery ” by Ulf Martin.

All of these are fully available online and easily findable in pdf. I am not one of these theorists. It is not in any way my project and I am not a formal student or contributor in any way to their project. I have no intellectual, reputational or financial interests in their project. I have only an interest in truth as defined by Charles Sanders Pierce.

“That truth is the correspondence of a representation to its object is, as Kant says, merely the nominal definition of it. Truth belongs exclusively to propositions. A proposition has a subject (or set of subjects) and a predicate. The subject is a sign; the predicate is a sign; and the proposition is a sign that the predicate is a sign of that which the subject is a sign. If it be so, it is true. But what does this correspondence or reference of the sign, to its object, consist in?” – Charles Sanders Peirce.

I have blogged a bit on their site as I blog at times on about three other economic sites.

The easiest way into their conceptions of money and financial capital in a ontologically scientific way is to read Fix’s essay. The monograph is comprehensive as one would expect. Martin’s essay is NOT postmodern in any sense, even if the title might lead one to think so. “Autocatalytic” is an empirical sciences concept applicable in social science if used carefully and correctly. “Pseudorational” is well defined in social science and (non-pomo) philosophy. “Sprawl” we understand from basic concepts like suburban sprawl.

Suffice it to say here, money and financial capital DO NOT measure value in any objective, defensible manner, either in CasP theory or in my (developing) and fully empirical ontology of formal and real systems. This is notwithstanding all the operations of money and markets. Money socially and algorithmically instantiates, tokenizes and makes operative , one important form of social power in our modern economic system. “Power’ in turn is conceptualized, by Ulf Martin, as the ability or capacity to create new conformations in reality against resistance. This an elegant definition of power which is conceptually operative from physics to the social sciences, albeit not in the same measurement units. But to reiterate, money does not measure value, at least not when you aggregate commensurable items in economics. And this is for all except absolutely identical items. Conventional applied financial economics spends most of its time attempting to aggregate (and aggregating in a bruitistic, mashing fashion) and value disparate items. I do not exaggerate. This very day you can find an actuarial statment of the value of your life in money. You can find a money value for x quantity of widgets. Thus there is some qunatitiy of widgets that equal your life or remaining life years at an estimated “hedonic” or amenity level.

Economics sounds absurd when expressed like that. I maintain it is absurd. That is not all of economics of course but it is much of classical and neoclassical economics. MMT may be a different cup of tea. I grant that. If MMT recognizes that the current rules for money, and not just for money but also for private property of all forms are wholly normative rules ostensibly intended to help all humans run a real economy in the real world and partially achieving that but also actually operating in extant, applied fashion to make a few people super rich, some intelligentsia, technical, administrative, “securitat”, apparatachik and artistic-propagandistic-entertainer classes (upper middle and middle) “accommodated” and the rest of he 8 billionimmiserated and oppressed while also rapidly and terrifyingly destroying the environment wholsale, then I will certainly agree with such MMT. We have a few decades left, if that, before catastrophe. The level of emergent and revolutionary change necessary in our concepts and our society are staggering. I seriously wonder if it is possible.

“Just trying to have a discussion”

I know Jerry, but I’ve discovered over a long time that sometimes words don’t do the dynamics justice.

Likely in this case it is just that words are insufficient and I can’t get the sense across. And I’m kinda busy trying to hit other writing deadlines.

Unfortunately I don’t have Bill’s masterful talent for writing of which I am always in awe.

No problems Neil. I always enjoy discussing this stuff with you and have learned a lot from you while doing that. Thanks for referring to me by my name also. It makes a difference even when you’re just telling me I’m wrong about something- which I admit happens more than I would like. The me being wrong about something I mean.

I always love Bill Mitchell’s rare responses to my comments. It will be like

Dear Jerry Brown,

And then some reasons I am wrong, or occasionally (often actually) an answer to a question.

Best wishes,

Bill

My hope is that one of these days I will actually be right about something …