In the annals of ruses used to provoke fear in the voting public about government…

RBA shows who is in charge as the speculators are outwitted

While progressive-sort-of politicians, at least they say they are progressive, work out all the ways they can parrot mainstream macroeconomics textbooks about fiscal deficits and public debt to make themselves appear ‘credible’, even using credibility in the title of key fiscal rules they advocate, the world passes them by rather quickly. British Labour is crippled by, among other things like Europe, their belief that the City (finance) is powerful and the state has to appease the interests of the speculators. The Australian Labor Party is no different and so it goes everywhere. Give a traditional social democratic politician any latitude and they privatise, cut welfare spending, deregulate, give handouts to the top-end-of-town and more. We have four decades of this behaviour to back that accusation up. Well one of the more conservative central banks in the world – the Reserve Bank of Australia – is currently demonstrating what Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) economists have said all along – the financial markets can always be subjugated by the power of government, any time policy makers choose to exercise their capacity. It is time that these progressive types realised that and became much more ambitious and, yes, progressive, really progressive rather than adopting the sycophantic stance that the ‘financial markets will destroy our currency’, which has undermined traditional social democratic politics.

RBA funding fiscal deficits update

While the officials in the RBA deny that their government bond buying program, which will continue for at least another year after this month, is funding the higher than usual fiscal deficits, it is patently obvious to most that this is what they are up to.

And, about time.

Please read these blog posts for discussion of this topic:

1. RBA governor denying history and evidence to make political points (July 23, 2020).

2. RBA governor adopts a political role to his discredit (August 18, 2020).

3. The Australian government is increasingly buying up its own debt – not a taxpayer in sight (May 26, 2020)

The facts are pretty clear.

As of today, the RBA has purchased $A68,250 million worth of Australian Government bonds under its so-called – Long-dated Open Market Operations.

If it continues in this vein, then it will hold about 25 per cent of all outstanding Australian government debt by about August 2021.

The Government politicians have not been saying much about this program for obvious reasons.

They don’t want the public to know that one arm of the currency-issuing government is accumulating a large proportion of the liabilities issued by another arm (Treasury) to follow the rise in the fiscal deficit.

If they explained what was going on in the real world to the public, it would become very clear that the central bank is effectively ‘funding’ a significant proportion of the increase in the fiscal deficit than any notion of some taxpayer account or the reliance on private bond markets.

It would also disabuse the public of notions that such coordination between the central bank and the treasury, which is at the heart of the understanding you get from learning about Modern Monetary Theory (MMT), is dangerously inflationary.

In their information sheet – Supporting the Economy and Financial System in Response to COVID-19 – the Reserve Bank of Australia outlines a number of policy innovations they are pursuing to help protect the economy and the financial system.

Among these measures they write:

Provide Liquidity to the Government Bond Market

The Reserve Bank stands ready to purchase Australian Government bonds and semi-government securities in the secondary market to support its smooth functioning. The government bond market is a key market for the Australian financial system, because government bonds provide the pricing benchmark for many financial assets. The Bank is working in close cooperation with the AOFM.

You can also view their more detailed explanation of what they are doing in this regard at – Reserve Bank Purchases of Government Securities.

The RBA is simply crediting bank reserves (the Exchange Settlement Accounts in the Australian parlance) in return for bond purchases.

These bonds have been issued in the primary bond markets and then bought and sold generally in the secondary market where the RBA buys them.

In its explanatory note, the RBA seems they need to set up the smokescreen in this way:

The Bank stands ready to purchase Australian Government bonds across the yield curve to help achieve this target. The Bank purchases Government bonds in the secondary market, and does not purchase bonds directly from the Government.

They could have added – ‘As if any of that matters’!

The point is that the primary bond dealers can reasonably anticipate that the RBA will purchase debt from them.

The complete data set is available via the RBA statistics – Monetary Policy Operations – Current – A3 – then go to the worksheet “Long-Dated Open Market Operations”.

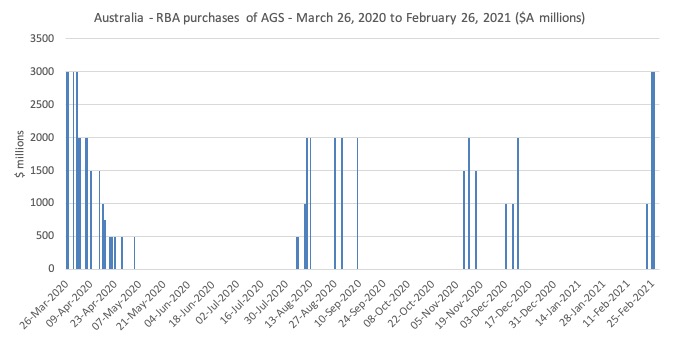

Here is the pattern of purchases of Australian Government securities by the RBA since March 26, 2020 up to today.

RBA can always control yields

The bond buying program has aimed to maintain a bond yield of 0.1 per cent on 3-year Australian government bonds, which the RBA says will “lower funding costs across the economy”.

The RBA said that:

The Bank stands ready to purchase government bonds to help achieve this target. The Bank purchases government bonds in the secondary market, and does not purchase bonds directly from the government.

So how does that work?

Australian government bonds are issued by the Australian Office of Financial Management (AOFM), which is a division of Treasury, via an auction or tender system.

The AOFM announces the terms of the auction, which included how much debt was available for sale, the maturity dates of the debt, and the coupon rate (the periodic interest to be paid on the face value of the bond).

The issue would then be put out for tender and then the bond dealers in the primary market would determine the final price of the bonds issued – thus taking discretion away from the elected government in terms of the yields that it would pay on government debt issuance.

As an example, imagine a $1,000 bond had a coupon of five per cent, meaning that you would get $50 per annum until the bond matured, at which time you would get $1,000 back.

At the time of issue, the bond market dealers desired a yield of six per cent to satisfy their profit expectations.

In this case, the initial specification of the bond is unattractive.

Prior to the adoption of an auction system (under neoliberalism), private bond dealers would avoid purchasing the bond under such conditions and the central bank would just provide the funds.

But under the auction system the private dealers could put in a purchase bid lower than the $1,000 to ensure they got the six per cent return that they sought on the price that they were willing to pay.

The bids will be ranked in terms of price (and implied yields desired) and the quantity requested in dollar terms.

The bonds are then issued in order of the highest price bid down until the volume the government desires to sell is achieved.

So, the first bidder with the highest price (lowest yield) gets their desired volume (as long as it doesn’t exhaust the whole tender, which is unlikely).

Then the second bidder (higher yield) receives their allocation and so on.

In this way, if demand for the tender is low, the final yields will be higher and vice versa.

It is important to understand that there is an inverse relationship between the traded price of a fixed income bond and its yield (rate of interest).

Why is that so?

The general rule for fixed income bonds is that when their prices rise in secondary markets, the yield falls and vice versa.

This is because if one pays more to purchase a bond, the coupon payments represent a lower return on the purchase price; on the other hand if one pays less, then the coupon payments represent a higher return.

Furthermore, the price of a bond can change in the marketplace according to interest rate fluctuations, even though the bondholder will still only get the face value of the bond back upon maturity.

When interest rates rise elsewhere in the economy, the price of previously issued bonds falls because they are less attractive in comparison to the newly issued bonds, which are offering higher coupon rates (reflecting current interest rates).

When interest rates fall, the price of older bonds increases as they become more attractive given that newly issued bonds offer a lower coupon rate than the older higher coupon rated bonds.

By way of example, assume a bond is issued at a face value of $1,000 and is paying 8 per cent per year for 10 years. The holder of that bond will recieve $80 per annum until maturity. This coupon yield remains constant throughout the life of the bond.

Now, suppose the bond is traded and you buy it for $800 in the secondary bond market.

Irrespective of the price you pay, the bond entitles you to receive $80 per year in coupon payments.

But now, the $80 payment per year until maturity represents a higher current yield than the coupon rate of eight per cent because it is based on your purchase price of $800.

The actual yield is $80/$800 = ten per cent.

The opposite happens when the central bank starts buying up the debt. It pushes up demand for the assets targetted which increases the price and as a consequence of the fixed coupon yield, drives yields down to whatever level the bank desires.

Enter the ‘all powerful’ (not) financial markets who think they can outsmart the RBA

On March 10, 2021, the RBA Governor gave a speech to a financial markets summit in Sydney – The Recovery, Investment and Monetary Policy.

He told the audience that:

1. “The RBA’s policy measures have been keeping financing costs very low, contributing to a lower exchange rate than otherwise, supporting the supply of credit to businesses, and strengthening household and business balance sheets.”

2. “The Reserve Bank is committed to continuing to provide the necessary assistance and will maintain stimulatory monetary conditions for as long as is necessary.”

3. He made a lot of points about only altering the short-term policy interest rate when the labour market was back to full employment and that would require faster wages growth.

I wrote a bit about that last week – We need trade unions to grow again (March 15, 2021).

But the relevant parts of the speech for today’s blog post related to its bond buying program.

4. “the Bank remains committed to the 3-year yield target … the Board has, though, discussed the question of whether to keep the April 2024 bond as the target bond, or to move to the next bond – that is the November 2024 bond – later this year.”

5. “We are prepared to undertake further bond purchases if that is required to reach our goals. Until then, we remain prepared to alter the timing of purchases under the current programs in response to market conditions. We did this last week when liquidity conditions deteriorated and bid-ask spreads widened noticeably, and will do so again if necessary.”

So they will keep targetting the 3-year yield as long as they choose.

It has become obvious that some speculators in the financial markets formed the view that the RBA would not continue its bond buying program.

Some background is that in February 5, 2021, the Governor appeared before the Commonwealth House of Representatives Standing Committee on Economics to present the RBA Annual Report 2019.

The – Transcript – reveals a nasty exchange between the Governor and the Andrew Leigh, Labor party (Opposition) Shadow Assistant Minister for Treasury.

He drank the mainstream economics Kool-Aid at Harvard and is anti-MMT but has never really come to terms of what we are on about, choosing instead, to trade on the usual ‘money printing’ claims.

Leigh attacked the RBA claiming that it had failed to achieve its inflation target and could have created more inflation if it had increased its QE program.

This is straight (erroneous) mainstream macro logic – QE is ‘printing money’ and more of it will create inflation.

Tell that to Japan, the US, Britain, the Eurozone, and more.

The Governor shut him up but he continued to call the RBA “timid”.

The Deputy Governor also noted that the AOFM had “issued very little under five years” in recent months. I will come back to that.

Leigh went on to accuse the RBA of being insular – “the bank hasn’t made an external appointment at the senior levels since the Spice Girls got together” and said that “amateurs rather than experts largely populate the board.”

The Governor said:

Your point about the Spice Girls-regrettably, it’s wrong.

And explained why.

He also defended the Board against Leigh’s amateur accusation.

It seems that this interchange lead some speculators to form the view that the RBA was reluctant to extend the QE program.

Several traders in the financial markets who ring me from time to time told me that there was growing sentiment that the RBA would abandon its control over the 3-year yield.

I was given lectures by financial market economists I know about the RBA losing credibility in this regard, which is a mainstream ruse that pretends the speculators are all powerful.

Of course, it is nonsense, but it seems that a significant number of speculators believed their own myths that they were actually running the show and so they started creating trading bets that the 3-year bond yield would rise as the RBA lost control.

How did they do that?

They started short-selling them, which means they offered future sales contracts on 3-year bonds, at higher prices than they expected to be able to buy in the spot market when the contract came due.

If correct, yields would have risen and they make a tidy profit when it comes time to deliver the contract.

The plan came unstuck dramatically.

Why?

1. Go back to the comment above about the AOFM not issuing many 3-year bonds. You can find the AOFM data – HERE – which if you do some digging will confirm that the issuance of bonds with that maturity has ceased.

Why is that important?

Well for the short-sellers, they had to get access to supply so they could deliver on their contracts.

If the supply was drying up, then the ‘markets’ would have to get the bonds off the RBA which has been buying them up in considerable quantities.

2. At the end of February 2021 (see graph above), the RBA doubled its purchases of the bonds, which drove the price up and ade it very expensive for the short-sellers to access them and make profit.

It also brought the yields on the bonds down sharply, thwarting the speculators’ hopes that yields would rise and prices would fall.

3. Then, in the Speech I opened with, the RBA told the ‘markets’ they would be expanding the QE program for at least another year and probably beyond.

Conclusion

So this little piece of history tells us who is in charge.

And it is not the financial market speculators.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2021 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

“The point is that the primary bond dealers can reasonably anticipate that the RBA will purchase debt from them.”

The mainstream counter argument I’m now seeing is how do they obtain the liquidity to do that given the ‘delay’ between auction and repurchase.

The BoE has a policy in the Asset Purchase Facility of not purchasing Gilts within a week of the auction:

“BEAPFF will not offer to purchase gilts newly-issued by the DMO within one week of their issue; and will not offer to purchase gilts which the DMO has announced it will re-open, including via a mini- tender, during the period one week either side of the re-opening.”

I expect other central banks have a similar “mourning period” to maintain the pretence – which likely means that the deposit holder institutions have to get involved in the process, not just the primary dealers. The primary dealers seem to operate highly leveraged on a super small capital base – as is typical of financial middlemen.

@Neil Wilson

The sooner the charade around bond issuance ends the better.

The mainstream know this scam is coming to an end.

This article: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-02-25/ross-garnaut-economists-unemployment-rba-government-critique/13186724 quotes Ross Garnaut who says

“We’re really arguing about angels dancing on a pinhead when we talk about a difference. ” Professor Garnaut told journalist Alan Kohler’s Eureka Report this week.

“The only difference between the Government selling bonds into the market and then the Reserve Bank buying them is you give a margin to the small number of players in the bond market, to the banks that participate in that trade

“I’d say, let’s take away their free lunch.”

But these charlatans still push neoliberal garbage like depoliticised fiscal authorities

Believe in the NAIRU

and push UBIs

It’s common to assume that states are cutting off regulation on financial markets.

It’s a neoliberal mantra that gets repeated over and over again: so much that we believe it’s true.

They say that governments get in the way of the “sacred” markets and that is supposed to be bad to everybody.

It’s the old trickle down hoax: if big business can make profits, so do small business, so do individuals. And we believe it’s true.

So we see now ponzi schemes everywere, because they are no longer “bad”.

But, all this is far from beeing de-regulated.

In fact, it’s heavily regulated.

It happens that the regulation doensn’t come from governmente, but from oligarchs.

It’s the gorvnement that is regulated.

That’s really interesting. Read so much recently about a similar thing happening in the US with ‘on the run’ treasuries and short sellers which drove the Repo rate negative.

bill, Thanks.