Well my holiday is over. Not that I had one! This morning we submitted the…

Britain confounding the macroeconomic textbooks – except one!

Remember back just a few months ago. We are in Britain. All the Remainers are jumping up and down about Brexit. We hardly see anything about it now as the UK moves towards a no deal with the EU. Times have overtaken all that non-event stuff. Now the developments are confounding the mainstream economists – again. There will be all sorts of reinventing history and ad hoc reasoning going on, but the latest data demonstrates quite clearly that what students are taught in mainstream macroeconomics provides no basis for an understanding of how the monetary system operates. All the predictions that a mainstream program would generate about the likely effects of current treasury and central bank behaviour would be wrong. Only MMT provides the body of knowledge that is requisite for understanding these trends.

Imagine we provide an intermediate macroeconomics class at almost any university in the world with the following facts:

1. According to the – IMF Policy Responses to COVID-19 Monitor – the government has just embarked on a massive fiscal expansion worth around 4.5 per cent of GDP.

In the previous year, government debt rose by 2.6 per cent of GDP. In the current year, it will rise by a further 10 per cent of GDP.

The official agency that helps the government on fiscal matters called this “the biggest ‘fiscal loosening’ from almost any government in almost three decades” (OMB)

2. The central bank has increased its “holding of UK government bonds and non-financial corporate bonds by £200 billion”, has “agreed to extend temporarily the use of the government’s overdraft account at the … [central bank] … to provide a short-term source of additional liquidity to the government”, has made direct “loans and guarantees available to businesses” worth 14.9 percent of GDP.

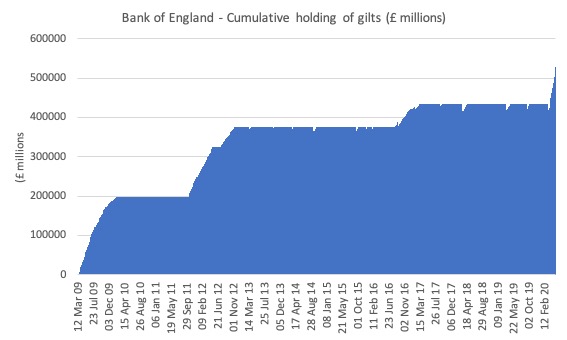

3. This graph shows the central bank’s holdings of government bonds (in millions of currency) and they dominate the total assets of the bank.

In the last three weeks (since April 22, 2020), the central bank has increased its holding of government bonds by 40,497 million.

What would the overwhelming number of students in the class conclude as an application of the theories they have been taught (dominated by New Keynesian thought) as a result of being confronted with these facts?

Well, many mainstream economists will deny this to avoid humiliation but I have done this exercise in the past with classes I have inherited.

The students would predict:

1. That the government bond yields would rise significantly as the auctions ensued after this sort of fiscal shift.

They would write explanations about how there was an increasing risk of inflation (too much money chasing too few goods) and the bond buyers would have to be compensated for that risk.

They would emphasise that this was especially going to be the case for longer-term bonds – beyond say two-years.

They would also introduce the argument that the risk of insolvency (credit risk) had risen and this required higher returns to bond investors to compensate for the elevated levels of risk.

2. The students would also argue that the willingness of bond investors to purchase the primary issues in the auction process (where government bonds are first issued) would diminish because of increasing fear of insolvency.

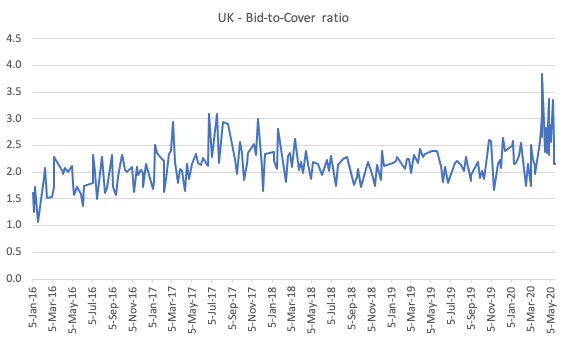

The better students who might explore the more technical literature about bond auctions would claim that the so-called bid-to-cover ratio would be falling in successive auctions as the fiscal deficit rose as investors got spooked about the situation.

3. All the students would suggest that the rate of inflation would accelerate, not only because of the fiscal deficit pumping cash into the economy but also because the central bank was obviously – in their words – ‘printing money like there was no tomorrow’ (or words to that effect – ‘printing’ would definitely figure strongly in their answers).

Most would conclude this part of their answer with a rather triumphant appeal to ‘don’t you know about Zimbabwe’ – as if that is the end of the story.

4. And, the more complete answers would then attempt to score bonus marks by introducing and applying the ‘loanable funds doctrine’ to argue that it would be obvious that interest rates would be rising and damaging private investment – fancy terms like ‘crowding out’ would dominate this part of the answer.

They would tell us that there is only so much saving (funds) to go around and that banks adjust loan interest rates to ration that finite pool of savings out among the competing demands for loans.

If the competition heats up – because the government is running large deficits and trying to get the cash from the loanable funds market to cover the tax shortfall on their spending – then the banks will push up interest rates and choke of investment in the non-government sector.

Some students, eager to impress that they belong in the community of economists and share the values they perceive to be a requisite part of membership would then extend this analysis of crowding out to introduce morality type stories about how governments waste resources because they are not disciplined by shareholders and by diverting scarce (finite) investment resources to wasteful government projects from ‘robust’ private projects (yes, the language would all be there – I have seen it in my career as a teacher), the overall well-being of the economy suffers.

Some might even go the next step and start talking about the government using up finite savings to build statues for dictators (seen that too!).

Confusion then enters

And then these characters consult the latest data and obviously get confused.

In fact, the problem is they don’t.

In his great 1972 book – Theories of poverty and underemployment, Lexington, Mass: Heath, Lexington Books), David M. Gordon wrote about how the mainstream deal with cognitive dissonance. Think denial.

His context was mainstream human capital theory, which at the time had been exposed as being deeply at odds with the facts about earnings distributions and other crucial labour market characteristics it sought to explain.

David Gordon said that mainstream economists continually responded to empirical anomalies with ad hoc or palliative responses.

So whenever the mainstream paradigm is confronted with empirical evidence that appears to refute its basic predictions it creates an exception by way of response to the anomaly and continues on as if nothing had happened.

Please read my blog – In a few minutes you do not learn much – for more discussion on this point.

That is a hallmark characteristic of a community crippled by Groupthink.

But the facts are so confronting that any one of these mainstream economists just embarrass themselves when they try to relate their theories and predictions drawn from it to the reality.

All the students in the mainstream courses would be given a deep F grade (fail) by yours truly if they presented that sort of answer to me. And I have done it in the past!

Latest data

The graph shown above documents the decisions of the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee to pursue quantitative easing in three different episodes.

The first episode started in November 2009 with the MPC announcing it would purchase £200 billion worth of government bonds.

In late 2011, the second episode began (after the shocking first two Osborne fiscal austerity cuts threatened to push the UK into a triple-dip recession) and the Bank purchased government bonds in the secondary markets to the take its holdings to £375 billion.

Then in August 2016, the bank launched a third, smaller quantitative easing program which not only combined gilts but also corporate debt. By the end of that episode, the total public debt holdings had risen to £435 billion.

On March 1, 2020, the Bank’s holdings had fallen slightly to £420.4 billion.

And the latest weekly data shows that on May 13, 2020, the holdings had risen to £529.5 billion, an increase of 25.9 per cent.

When all this ‘comes out in the wash’, the Bank of England, like many central banks now engaging in large-scale government bond purchases in the secondary markets, will have basically bought all the debt issued by the British government in pursuit of its fiscal stimulus.

Right-pocket of government working with the left-pocket. Take your pick which pocket is the bank and which one is the treasury.

It doesn’t really matter does it?

And yields?

The UK Debt Management Office provides detailed data on the – Gilt Market.

The latest data shows that on May 20, 2020, the UK government issued a three-year Gilt (bond, expiring in 2023) worth a total of £3,869 million (quite a tidy sum) at a auction yield of -0.003%.

A week before, they issued £2,250 million worth of 21-year Gilts (maturing in 2041) at a yield of 0.594 per cent.

And on May 6, 2020, they issued a 34-year bond totalling £1,750 million at 0.495 per cent.

Now make sure we know what the latest auction means.

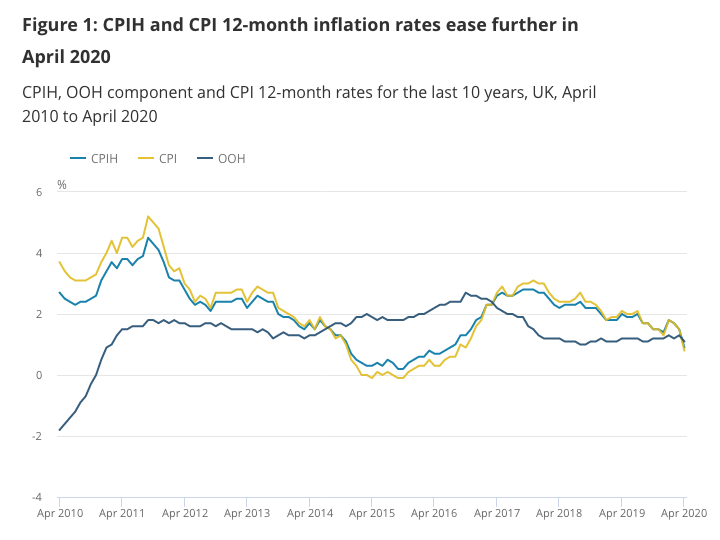

Well we need to tie it together with the latest release from the Office of National Statistics (ONS) – Consumer price inflation, UK: April 2020 (May 20, 2020) – which showed that the annual CPI inflation rate was 0.9 per cent in April 2020, down from the March reading of 1.5 per cent.

For the last two months, the monthly inflation rate for CPI including housing costs (CPIH) has been recorded at zero.

The one month CPI series was zero in March and -0.2 in April.

In other words, generalised price inflation is negative (that means prices fell in April) while the Bank of England was merrily adding £200 billion to bank reserves in exchange for gilts – which means it was effectively covering all the deficit increase.

Who would have thought! Certainly not the students we started this post by interrogating.

Here is the graph provided by ONS (Figure 1) which compares the CPI including with the owner occupiers’ housing costs (CPIH), the CPI itself (CPI) and the owner occupiers’ housing costs (OOH) component (the latter which “accounts for around 16% of the CPIH” and, is therefore, the “main driver for differences between the CPIH and the … CPI inflation rates”).

And the clear signal from the Bank of England is that the bond buying is far from finished.

As the fiscal deficit rises and the government issues matching debt (making sure you understand that there is no necessity for this in relation to the expenditure capacity the government has), the Bank will be out in force buying up all the debt.

Talk about ‘money printing’! The students would be getting feverish.

Pity they don’t understand it is a non event – right and left pockets remember.

It doesn’t do anything to increase the capacity of the government to spend. All it does is offer a portfolio swap for the non-government sector – reserves for bonds.

Now why does that matter for the bond auction?

The negative yield on the latest gilt issue means that the investors are paying a ‘tax’ (sort of) to the government in order to give them transfer bank reserves held by the banks back in return for a nominal public liability.

Effectively, the central bank just shifts numbers from reserve accounts to government debt accounts and a nominal liability on government is incurred.

It has to pay back £3,869 million in 2023. A nominal position.

Whoever holds those gilts to maturity will get back less than they paid (as a result of the negative yield).

What does that signal?

First, in the words of the Financial Times:

The robust demand underscores the appeal of gilts, long considered to be a haven due to the UK’s strong creditworthiness and economy. It also suggests market fears over the large increase in borrowing the UK has undertaken due to the Covid-19 pandemic has not yet weighed on market appetite for the debt.

There is that word – “robust” – again, in a meaningful context this time.

Second, the strong demand for the gilt issue and the negative yields means that the investors do not think that there will be an outbreak of inflation any time soon.

And the fact that 34-year gilts were yielding just 0.495 per cent reinforces that point clearly.

Third, this also means that the bond markets think that the Bank of England will try to push their policy rate down further from its present value of 0.1 per cent.

Further, that means negative!

And so the whole business model of neoliberal investing is being shot to pieces by the reliance on monetary policy ‘to generate inflation’.

We don’t know what the longer term consequences of this weird pandemic are going to be. But you can bet the storyline is going the way the mainstream economists predict.

Bid-to-cover ratios

What about that robust demand for the gilts?

Well, this relates to the concept of bid-to-cover ratios.

I wrote about bid-to-cover ratios in these blog posts (among others):

1. Bid-to-cover ratios and MMT (March 27, 2019).

2. D for debt bomb; D for drivel (July 13, 2009).

Essentially, the bid-to-cover ratio is just the the $ volume of the bids received to the total $ volumes desired. So if the government wanted to place $20 million of debt and there were bids of $40 million in the markets then the bid-to-cover ratio would be 2.

The financial media are always predicting the ratios will fall as investors give up on buying government bonds.

It is not even a case of the dead clock being correct twice every 24 hours. These predictions are never correct.

Here is the record of bid-to-cover ratios from January 5, 2016 to the latest gilt auction on May 20, 2020.

That is the ‘robust’ demand the FT was talking about.

The ratio was 2.15 for the negative yield May 20, 2020 auction. That means that the investors actually wanted to buy bonds worth £8.32 billion (that is what they bid for) but the government rationed the corporate welfare out at £3,869.624 million.

And as the pandemic struck and the deficits have risen, the ratio has been rising.

And the average ratio over the period shown has been 2.18 – more than twice the debt wanted than issued.

How does the mainstream explain that in an environment of rapidly rising deficits and huge bond buying from the central bank? They cannot!

Conclusion

So you can see the students haven’t done very well have they?

The reason is that the mainstream macro framework is incapable of explaining anything of importance – I actually haven’t found it useful for unimportant things either.

Only MMT provides the body of knowledge that is requisite for understanding these trends.

And I didn’t get to talk about the massive central bank payments (like up to £57.6 billion) to the large corporations in Britain that have been revealed by the Bank of England under freedom of information requests – see Update to the Covid Corporate Financing Facility (published May 19, 2020).

Where did that money come from? Just kidding.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2020 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Hi everyone,

I’ve never quite understood how “mainstream” economists can at the same time argue that “the rate of inflation would accelerate […] because of the fiscal deficit pumping cash into the economy”, and

“There is only so much saving (funds) to go around”

Obviously, if you’re “pumping cash into the economy”, there’s not “only so much saving to go around”. Can anyone clarify that to me?

Thanks,

Alex

They’re just wrong headed.

They have yet to realise that government spending causes taxation that matches the spending to the penny for any positive tax rate.

And it does that instantly *unless* people slow down the process by holding onto their money for a period of time. A process known as “saving”.

Saving is having money in your hand. Any pause between earning and spending, no matter how short, causes saving to occur. And that saving, when netted off against loans issued, has precisely the same economic effect as taxation.

The mental model is wrong. They are the sort of people who would sit in a Hot Tub and fret about turning the heating pump on in case the tub ran out of water.

Alex, I think the ‘mainstream’ would say that as long as the government deficit was being ‘funded’ by bond issuance purchased only by the private sector, then at that point you are not looking at inflation but possibly avoiding deflation in some recessionary circumstances. What you might see is that interest rates on the bond issuance get driven upwards because of the increased demand for those limited savings however.

They might also say (and definitely used to say) that if the central bank got involved in buying any of that through money creation then that would be inflationary. They have toned it down a bit since the great recession where that was proven wrong.

The government, with its tool the central bank, can just create money whenever they see fit to do so. So there is really not “only so much saving to go around”. Ever. Unless you are already in a state of complete full and best possible employment of all resources. And past that point you see inflation.

“Pity they don’t understand it is a non event – right and left pockets remember”

I’ve done a bit of digging on this over the years. The left pocket (the loan asset) is called the National Loans Fund and the right pocket (the deposit liability) is called the Consolidated Fund. These sit on the balance sheet of the Bank of England. During the day when the Consolidated Fund runs a bit short, the Debt Management Office increases the size of both the National Loan Fund and the Consolidated Fund by, say, £100m.

Loans create deposits – right on the face of the BoE balance sheet.

There is an operational constraint on the National Loan Fund that is it cleared by the end of the day. That’s normally where the Gilts come in.

“And the average ratio over the period shown has been 2.18 – more than twice the debt wanted than issued.”

Interesting to explain why this is, which is something that MMT reveals but nobody else does.

When government marks up somebody’s account with £100, you end up creating several £100 assets along the banking chain.

A £100 asset at the central bank – the National Loan Fund

A £100 asset at the clearing bank – their bank reserve deposit

A £100 asset for the individual – their bank deposit at the bank.

And if they are using a building society (or other non-clearing intermediary) then the individual has a £100 asset with the building society, and the society has the £100 bank deposit with the clearing bank.

What MMT tells us is all those operations can bid for the Gilt, which means you can get up to 4 bids of £100 using the same £100 of “deficit” the DMO is trying to eliminate: one from the individual, one from the building society, one from the bank and even one from the Bank of England themselves.

So when mainstream is scratching their heads wondering how the bid cover is so high, you can chuckle quietly to yourself.

@Neil W,

But as soon as any *one* of those asset holders actually *buys* £100 worth of Gilts, then all those £100 assets instantly disappear from the whole chain of accounts, as the Gilt purchase clears – so only one party can complete the purchase.

Also, small niggle, but I was under the impression that the “third asset”, as an individual, can’t actually bid for Gilts? They could certainly add to govt (so-called) debt, by purchasing NS&I, ‘Granny’, or Premium Bonds, but aren’t Gilts are only sold to institutional investors?

Best, Mr S

Actually that would only affect any party further up the chain I guess, so I’m wrong there – whoops!

On bid to cover ratios, I gave a talk to a local transition group recently, and wanted to try and get across the idea to them that if they stopped and actually thought about things from any perspective of borrowing money they recognise, the mainstream depiction of government borrowing simply couldn’t make sense…

So had an idea to pitch the government as a business proposition to Dragon’s Den. I know not a great analogy as in the den you’re not just borrowing money, but I thought would be more fun than re-enacting a sit down with your bank manager. The plan originally for a live talk was to have members of the audience reading out the questions from each dragon to make it more interactive (with cards I prepared), so lost a bit via zoom anyway – plus Penny (the meeting host) and I nailed it a lot better in rehearsal than live (when we mucked up mute/unmuting the audience/ourselves), but think it just about worked and got some chuckles with the punch line.

Thought I’d share as a bit of fun, and maybe some feedback on other ideas of how to get the message across in ways to people how never usually think about economics…

Link below begins at the start of the game:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gdKAnhzTOK8&t=29m52s

“When government marks up somebody’s account with £100, you end up creating several £100 assets along the banking chain”.

I don’t question the truth of this. I just find it totally bewildering. How can one input replicate itself four times? ie be counted four times over as each single one of four discrete parties’ wealth?

I suppose my inability to comprehend this (which to my simple mind is just fraudulent) disqualifies me from taking part in this discussion – and also explains why I’m not a billionaire. I’ll just have to be philosophical about that, because there’s no way I’m ever going to be able to understand why it doesn’t lead to anybody going to jail as it rightfully should.

But surely I’m not alone? How can it possibly be thought that this kind of book-keeping conjuring-trickery, flying as it does in the face of anything most people’s ordinary commonsense (let alone notions of moral behaviour) would think of as legitimate, could *ever* be satisfactorily shown to the man or woman in the street to be perfectly legitimate?

It can’t be. Does it deserve to be?

“… I actually haven’t found it useful for unimportant things either.”

Comedy gold

“I just find it totally bewildering. How can one input replicate itself four times? ie be counted four times over as each single one of four discrete parties’ wealth?”

Because for all but the final holder of the asset (the individual with the building society deposit), there is a matching liability in the accounting. So the government has a net liability, and the final holder has a net asset, the others in between (the bank and, if present, the building society) are just intermediaries.

The respective bids for the gilt just come from the different ways one of the assets in the chain gets swapped for an interest bearing one.

Initially:

Government has liability in reserves; bank has asset in reserves matched by deposit liability to building society (BS); BS has asset with deposit at bank, and deposit liability to individual; individual has asset with deposit at BS.

So the outcome options are:

1) bank buys gilt with it’s reserves: government has liability in gilt, bank has asset in gilt matched by deposit liability to building society (BS), BS has deposit asset with bank matched with deposit liability to individual, individual has net asset in form of BS deposit

2) BS buys gilt: government has liability in gilt, bank assets/liabilities cancelled, building society has gilt asset matched with deposit liability to individual, individual has net asset in form of BS deposit

3) Individual buys gilt: government has liability in gilt, bank assets/liabilities cancelled, building society assets/liabilities cancelled, individual has net asset in form of gilt

So the three potential bids there are just “competition” for each of those different outcome options.

The 4th potential bid (from the BoE) just maintains the original position (it’s as if the gilt never gets issued), so that the 4th competing option.

“But as soon as any *one* of those asset holders actually *buys* £100 worth of Gilts, then all those £100 assets instantly disappear from the whole chain of accounts”

I can see I’m going to have to do a video on this one. I thought I might when I did the one on Gilts the other day.

Sometimes it’s like being the Masked Magician – revealing the secrets behind the trick.

“Also, small niggle, but I was under the impression that the “third asset”, as an individual, can’t actually bid for Gilts?”

Yes that is the impression they like to leave you with isn’t it. Fortunately with the UK we never ever get around to repealing things and tidying them up. So the old facility to buy Gilts directly that used to sit with National Savings last century is still there hiding at the Debt Management Office. Look up “Approved Group”.

It’s fairly easy to get on it. I did just to check it was still possible.

“So the old facility to buy Gilts directly that used to sit with National Savings last century is still there hiding at the Debt Management Office”.

Neil, out of interest, how does that actually work, technically? Are you putting the bid in via a bank? I presume ultimately they’re still acting as an intermediary? Do they force you to have sufficient deposits with them to make the bid (given you don’t actually have the means to directly get hold of reserves to meet your bid, so if you were short, you can’t just obtain them by other means like a bank)?

“… I actually haven’t found it useful for unimportant things either.”

My work computer monitor got “upgraded” to one without a height adjustable stand. Some solid hardcover textbooks do the ideal job for height adjustment, the only drawback being you don’t want to use a book you’d ever like to read…

Thus would never dream of using one of Bill’s tomes for such purposes, but perhaps some use for all those copies of Mankiw cluttering up libraries in economics departments around the world?

one thing I’ve thought perplexing as well is that govt spending that is ‘financed’ by borrowing is somehow not inflationary but ‘printing money’ is.

If anything borrowing is more likely to cause inflation, my reasoning is this. In both cases the original spending happens now, and this increases demand for whatever was bought by gov.

But if the gov borrows, then it also spends money paying interest at maturity. It also delays the injection of cash until maturity as well.

So if we had a $1b purchase “today” by gov

1) ‘print money’ option…increase demand+possibly inflation for what the government buys with it’s $1b. economy has $1b more dollars than “yesterday”

or…

2) ‘borrow money’ option…increase demand+possibly inflation for what the government buys with it’s $1b. gov also sells bond for $1b. the economy has same dollars “today” as it did “yesterday”. but…”tomorrow” govt pays $1b + interest to whoever holds the bond.

economy has $1b + interest extra dollars “tomorrow” compared to “yesterday”.

This surely puts additional inflationary risk being cause by the extra interest payment dollars that are accompanying the govt spending.

It’s almost the definition of inflation – paying more than necessary to produce goods or services. The gov doesn’t need to pay interest, but it chooses to.

Hey robertH,

Michael Berks explained it quite well. No trickery, no fraud. But I think I can simplify it a bit for you using a simpler example. It’s not to illustrate how bid-to-cover can be so high, but to illustrate something much simpler which is at the core of what you think is chicanery.

Suppose you have account balance = $0.0 on your credit card.

Then you see the Gov is selling gilts, and you want to get one.

So you take out $100 from the ATM against your credit card, and buy the gilt.

Congrats. You own a gilt. Even though you started with nothing but an empty credit card.

Where’s the fraud? There is no trickery or fraud. What you did was just dopey. You will pay around 6% interest on your credit card debt of $100 and earn 2% interest holding the gilt. Sound like a good deal for you? Hey. Never mind. You own a gilt!

What about the bank purchasing the gilt from it’s reserves added to by the depositor? Why would it do that? Is it also being dopey? Probably not. They might pay the deposit holder 1% interest, but if the gilt pays them 2%, they’ve won. So they can afford to take the hit to their reserves. You can always make a little money off interest without starting with anything provided someone will loan you cash at lower interest than you can collect on some other redeemable asset. Problem is, why wouldn’t the dude loaning you the cash grab that asset themselves ahead of you, so there aren’t too many such arbitrage deals you can find, unless you own a bank.

“When government marks up somebody’s account with £100, you end up creating several £100 assets along the banking chain”.

It’s odd how gold-standard thinking hangs around. We (me too) try to think of these assets as distinct things. They’re not. With modern fiat money, each of these assets is a contractual claim against the same underlying “thing”.

My money on deposit at the Credit Union is in essence a deal where the CU promises to use their money (typically in their reserve account) to do my business.

But “their money” is a deal with the Central Bank where the CB promises to use its money to do the CU’s business.

And the CB’s money is just a number that they maintain, representing some amount of aether or phlogiston or something that the National Market will take to be purchasing power.

It helps to think in quadruple-entry bookkeeping here. It sounds exotic, but it’s not. Wikipedia doesn’t describe it, but a web search will turn up some authoritative descriptions.

We all have some general idea of double-entry bookkeeping, where an individual enterprise keeps accounts with balanced pairs of debit and credit entries. The debits and credits balance as a consistency check. This is OK for an individual’s accounts but it won’t do for economic modeling, or writing computer games around imaginary societies.

Q-E bookkeeping simply recognizes that every deal has (at least) two parties, and each party keeps credits and debits in its accounts. Q-E bookkeeping writes up each deal as a credit+debit for the seller and a debit+credit for the buyer. Q-E bookkeeping will trace the chain of credit↔debit from party to party in a deal, or a series of deals that we see in our story of asset creation here. The mystery goes away when you see the totality of what’s happening.

I was reading some history here, I don’t remember specifically what it was, but the comments to one of bill’s 2009 articles discussed Q-E bookkeeping. We knew about it then, but we seem to have forgotten.

“Neil, out of interest, how does that actually work, technically?”

First you pretend it is 1989. Then you send a cheque to the Gilt registrar in Bristol at the non-competitive bid price along with a filled in application form.

They then send you a paper certificate with a pretty gold edge.

For example the 4.75% Treasury Gilt 2030 auction on 10 March 2020 had a non-competitive bid price for the Approved Group of £151.50 per £100 nominal.

The more we get into the details and nuances of MMT–no, I should say into the details and nuances of the neoliberal financial machinations designed to create the false impression that sovereign currency must be linked to debt–the more we lose the stunning clarity and power of the MMT lens. Fiat money flowing from the elimination of the gold standard, fiat money which is now the sole province of the federal government to create via spending decisions, fiat money which is nevertheless constrained by available resources (in order to avoid inflation) and the overriding constraint of the health of our planet (in order to continue living)–such fiat money is the sole elementary truth required to spread the MMT gospel. No, that’s not quite right either. IT IS THE GOSPEL. All the rest of MMT, as illustrative and interesting and helpful as it may be, is theology. Michael Berk’s linked video (thank you for it, Michael) eventually gets there and effectively hammers the essential point home, but even it spends too much time and energy IMHO attempting to correct error rather than proclaim truth.

“First you pretend it is 1989.”

Right, you’ve sold it to me already. Michael Thomas… It’s up for grabs now… Next summer will be Italia ’90 and the favourite summer or my life. And I get a shiny bit of paper with a pretty gold edge.

Admittedly I’m only 6 years old and didn’t have access to a chequebook*, but maybe dad could sort for me out of my post office account.

If Bill has any college students reading you might need to elaborate on what a cheque is ;o)

When you think about it, MMT tells us that, in countries with monetary sovereignty, the national government never deals directly with the public in financial transactions. Likewise, the public cannot deal directly with the government. Everything must go via the banking system.

Maybe we could even say that the public never has direct access to the national currency (except in the physical form of banknotes and coins, which represent a tiny fraction of all the currency outstanding).

It could be argued that the currency only exists in the form of “reserves” at the central bank, where the only account-holders are the national government and authorized banks. These reserves are continually transferred between these account-holders but never leave the central bank.

Excluding physical cash, the public can only make and receive payments (or save) in the form of bank deposits, which are IOUs issued by banks (unlike national currency units, which are IOUs issued by the government).

The bank IOUs are of course denominated in the national currency, since it is the unit of account.

In effect, the bank IOUs represent a promise to customers to transfer a certain quantity of national currency to another account at the bank or another central bank account-holder (or to deliver it in physical currency to the customer herself) at some time in the future. But it doesn’t confer access to or ownership of the national currency itself (again, excluding physical cash).

Neil,

“They have yet to realise that government spending causes taxation that matches the spending to the penny for any positive tax rate. ”

Which implies there can never be a government deficit!

Henry, wouldn’t the government spending in any one period eventually be recaptured in taxes over a number of periods? I think it would. And that recapture of spending will never be obvious as the government continues to spend. So there will be a deficit for most any period of time- especially if I can select those time periods 🙂

“Which implies there can never be a government deficit!”

There never is in the mathematical model.

It’s only when you introduce friction in the time dimension – as in entities who don’t spend their money the instant they get it – that you end up with a deficit.

Which is why neoliberalism tries to push people into debt – so that everybody ends up like that person who is always broke on pay day. That’s their ideal condition.

I doubt it is yours. Or mine.

What I find amusing is the hypocrisy. Neoliberals can cope with the idea of a friction buffer in unemployment (that’s what they try and cast the NAIRU as: “Wait unemployment”), but they can’t cope with the idea of a friction buffer with government spending (aka net saving of the private sector).

This is a ‘Thatcherite monetarist’s’ ‘take’ for the U.S.?

Around the 6 April 2020 he stated:

“Variations in the ratio of money to nominal GDP (or “velocity”) do occur, but large variations are unusual. In the medium term they are ironed out as the underlying stability of agents’ money holding behaviour takes over. It follows that – at some point in the next two/three years – the growth rate of US nominal GDP will accelerate towards a figure in the teens per cent. Given that the trend growth rate of real output is not much more than 3% a year, a big resurgence in inflation is implied by our analysis. The only way to prevent this is for the Fed not just to end its current stance as ready financier of the government deficit, but to withdraw the money stimulus (i.e., to cause the quantity of money to fall by the “excess over normal growth” now being recorded.). In a Presidential election year, that seems very unlikely.”

Around April 23 20120:

“13:07 it’s very clear that in 2020 there’s

13:11 going to be a fall in nominal GDP so a

13:15 dramatic fall also in velocity

13:19 there’s obviously money growing a kind

13:21 of 15-20 percent and omelet GDP actually

13:24 going down a bit but then what happens

13:26 through in 2021 and 2022 when in all the

13:30 history these things reassert themselves

13:32 I didn’t know the precise course

13:34 quarterly course of inflation

13:36 GDP and so on all I know is that there’s

13:38 a very difficult adjustment problem

13:40 coming up out there in the next few

13:42 quarters of course at the moment there’s

13:47 the oil price fall it’s going to dampen

13:49 down inflation that may lead some

13:51 complacency you may think that it that

13:55 the worry is deflation not inflation

13:56 okay each user in my view there’s a lot

14:01 of analysis a lot of previous history a

14:05 lot of theory behind the forecast that

14:08 there’ll be a sharp increase in American

14:10 inflation in the next two or three years . . . ”

It appears that ‘V’ is not as stable as the ‘Monetarists’ believe?

But, there is going to be ” a sharp increase in American inflation in the next two or three years . . . “

@Norman

“It could be argued that the currency only exists in the form of “reserves” at the central bank, where the only account-holders are the national government and authorized banks”.

SFAIK there’s nothing *intrinsic* which prevents every citizen having an own individual account at the central bank. Indeed exactly that thought has been floated by none other than the Bank of England itself.

Doubtless that would throw up its own set of problems but there’s no reason whatever to suppose that they’d be inherently intractable.

Citizens would then be enabled, to the extent that they preferred, to settle payments with one another and between themselves and corporate entities without the intermediation of banks.

“Doubtless that would throw up its own set of problems but there’s no reason whatever to suppose that they’d be inherently intractable.”

The system largely already exists to do that. Now we have faster payments and Current Account switch processes, then really its just a case of changing the ownership of the accounting records.

Likely the commercial banks will still act as ‘agent’, but if the bank went bust all that would happen is you would switch agent. The data records would stay the same. The format and logo on your statement would change.

And that’s why the banks resist the change. Managing deposit and current accounts directly on their balance sheet makes it more difficult for the central bank to put them into administration if their loan book goes bad.

Whereas if the central bank was the entire liability side of a commercial bank (as would be the case if entity deposits were moved to the Issue Department of the central bank), it could put the bank through administration any time it felt it was appropriate. The loss would then accrue to the central bank – as it should since they were supposed to be regulating the bank.

@Michael Berks

@Bijou Smith

@Mel

“What MMT tells us is all those operations can bid for the Gilt, which means you can get up to 4 bids of £100 using the same £100 of “deficit” the DMO is trying to eliminate: one from the individual, one from the building society, one from the bank and even one from the Bank of England themselves” (Neil Wilsonj.

Homing-in on that, what it *says* is that three separate bids each of £100 can be made on the basis of the same £100 by which govt initially marks-up somebody’s account. Accepting that it is fiat – ie a token – is one thing. Accepting that it can legitimately be used to pay simultaneously for three “things” priced at £100 each (total = £300) would be tantamount to accepting that a swindle is not a swindle, it seems to me. As it stands, I can’t accept that proposition.

“But as soon as any *one* of those asset holders actually *buys* £100 worth of Gilts, then all those £100 assets instantly disappear from the whole chain of accounts, as the Gilt purchase clears – so only one party can complete the purchase” (Mr Shigemitsu)

Now THAT I can understand, and accept.

But which proposition is true? And if both are, each in its own separate universe, what is the practical utility of deploying the unintelligible (IMHO) one in the public space at all – as distinct from specialists using it in a specialised context in which it does actually convey meaning, and is true and properly understood because appropriate *to that specific, narrow, context*?

I’m most grateful for your attempts to instruct me but I’m sorry to say that I’m no less baffled than I was to start-with. More importantly, if I am (as I believe I am) not wholly untypical of the Great Unwashed in this regard, my bafflement can be presumed to be shared by (say) 95% of the public. If true, where does that leave MMT’s chances of ever taking over the reins of power if – as Neil starts out by declaring – this is “is something that MMT reveals but nobody else does”? “Reveals” to whom and to what purpose? is my question.

As I’ve already said, I’m resigned to the realisation that I’m never going to understand this no matter how hard I try. But as I’ve also said that goes for an awful lot of people (or should that be “a lot of awful people”?) other than just little me.

@ Neil Wilson

Thanks for the comment, which I think I understand in principle (the accounting language confuses me but that’s my problem).

Though this:-

“And that’s why the banks resist the change. Managing deposit and current accounts directly on their balance sheet makes it more difficult for the central bank to put them into administration if their loan book goes bad”

whilst true, at the same time strikes me as being a masterpiece of understatement!

The one crucial factor IMO which before any other causes the mega-commercial-banks to be “too big to fail” is their existing collective monopoly-status within the payment system. It’s what causes them to be systemically indispensable because there’s no government that doesn’t recoil at the prospect of having a country’s entire payment system ceasE to function due to the chain-reaction effect of one major bank failing. With the result that BIG “banks whose loan-books go bad” can always rely on being automatically bailed-out by government. *Our* governments are *their* hostages.

Whatever it takes to break that monopoly and put an end to “TBTF” ought to be done. It’s just a matter of choosing the most efficacious means, isn’t it?

Dear All above,

Especially, for ‘those’ who are in despair after reading all or some of the comments, i would strongly recommend an article, I read sometimes ago, titled:

‘Repeat After Me: Banks Cannot And Do Not “Lend Out” Reserves’

[Bill edit: Link is correctly supplied by Henry Rech below]

I think this article will clear things up for us.

The reasons I write this is because after reading all the comments, i got more confused, and has not learn anything more than I had begun with.

However, in the mist of confusion, to a point of half fainting, a thought came to my mind – wait a minute, i had learned all about this before by a wonderful article.

This article helps me understand about the reserves in the banking system. And once i realized that, my mind became clear again.

So, I strongly recommend it to us.

After reading it, I will be pleased to hear any comment you may have.

Wishing us all a nice weekend!

vorapot

Neil Wilson,

“There never is in the mathematical model. ”

Depends on the marginal propensity to consume, the tax rate and whether investment is a function of income.

I don’t think “never” is applicable.

I don’t understand too well private (or central) bank activities, but isn’t it true that they only became powerful operators once they were released from controls, in particular to engage in the residential mortgage market? Banking used to be a respectable but borrowing profession which provided a useful service: lending for consumption and real investment. This is why it’s important to recognise the destructive role which the land market plays in the economy and how simple (technically but not politically) it could be to fix it.

@robertH

“Accepting that it can legitimately be used to pay simultaneously for three “things” priced at £100 each (total = £300) would be tantamount to accepting that a swindle is not a swindle, it seems to me. As it stands, I can’t accept that proposition.” (robertH)

“But as soon as any *one* of those asset holders actually *buys* £100 worth of Gilts, then all those £100 assets instantly disappear from the whole chain of accounts, as the Gilt purchase clears – so only one party can complete the purchase” (Mr Shigemitsu)

There’s a middle ground between those two statements, that I tried to explain in my original post, but will try and so differently below.

Firstly, the three things can’t happen “simultaneously”. The three outcome options (bank owns gilt, BS own gilt, individual owns gilt – or 4th outcome if you include BoE buys gilt) are mutually exclusive. So in the event one occurs, the other *bids* disappear, and “only one party can complete the purchase” (as Mr Shigemitsu said).

Where I’d disagree with what Mr Shigemitsu said is “then all those £100 assets instantly disappear from the whole chain of accounts”.

I’d say they disappear *up to the entity in the chain that purchased the gilt*. Again, the outcome options in my original post should show why.

So if the the individual buys the gilt, the whole chain of assets/liabilities of the intermediaries between the government and individual disappears, and the individual ends up with an asset that is a direct liability of the government (the gilt)*.

But in either of the other scenarios, that chain of intermediaries still exists.

Let’s leave out the building society as that just complicates things (but you could extend to any number of intermediaries without changing the logic), so just deal with the case of the bank buys the gilt.

The chain of matched assets/liabilities is still**:

– Government/central bank has liability to commercial bank

– Commercial bank has asset with central bank, liability to individual

– Individual has asset with bank

All that has changed is the form of the liability/asset between the central bank and the commercial bank (it was reserves, and now is a gilt). The important point is the commercial bank (or any other intermediary in the chain if we added more) don’t extinguish (or change) their *liability* in the chain.

They just get to bid for the right to exchange the asset side of their matched asset/liability in the chain.

This may be beneficial to them, if their new asset (the gilt) pays out interest, whereas their old asset (reserves held at the central bank) didn’t. But what happens if the individual, who still holds their asset in the form of a deposit at the commercial bank, uses that deposit to pay someone at another commercial bank (or withdraws it as cash)? In isolation, the bank now doesn’t have the right *type* of asset – they need to find reserves to transfer to the other bank, but they swapped the reserves for a gilt.

Of course the point is (as Neil always likes to remind us), you can never think of these things in isolation. In the real world, with all the other customers, payments etc. the bank makes this work operationally – either they have surplus reserves from elsewhere, or they sell their gilt, or if they’re really stuck, borrow from the central bank at the discount window. As long as they’re solvent and there’s enough liquidity in the system the show keeps rolling on. So it (bidding for gilts and on-selling them in secondary markets) just becomes an operational issue for them.

Similarly, from the individual’s point of view, they don’t necessarily want to tie their money up in a bond (even though it would earn interest for them), as they want the deposit in their account.

So it isn’t as if all the outcome options are always bidding for every gilt. But as Neil’s original post says, it does show why when you introduce intermediaries into the chain (and choose to sell gilts in the first place), you can end up with multiple different entities all bidding for the same asset from the same asset/liability chain.

But again, just to re-emphasise – an intermediary swapping the form of the assets they hold in the assets/liability chain doesn’t remove or change their liability. Hence no swindle! Other than banks getting profiting risk-free interest obviously…

*This brings to mind the Kalecki quote of governments spending in gilts, but can’t remember it properly or find with a quick google, if anyone else want to add…

**While we’re tagging people, I’d second @Mel’s post about thinking of this in quadruple-entry accounting. Just writing out the various assets/liabilities in a spreadsheet makes things much clearer (and saves a lot of words!). If I could embed a table in comments I’d do so.

“Depends on the marginal propensity to consume, the tax rate and whether investment is a function of income.”

You obviously have a different mathematical model in mind that I do. I’m talking about a geometric expansion of the spending chain. That will sum up no matter what the tax rate. All that changes is the number of cycles to get there.

Neil

“You obviously have a different mathematical model in mind that I do.”

I’m referring to the standard models of income determination.

Changes in variables (such as a change in government spending) move the equilibrium point. At the new equilibrium point, a zero budget balance occurs only under certain conditions.

Your “geometric expansion of the spending chain” is the standard multiplier process which underlies the standard model of income determination – it has a theoretically calculable limit. Only under certain conditions does it produce a balanced budget.

vorapot,

Your link does not seem to work.

This one should:

https://www.hks.harvard.edu/sites/default/files/centers/mrcbg/programs/senior.fellows/2019-20%20fellows/BanksCannotLendOutReservesAug2013_%20(002).pdf

At least on my browser the link works but you need to type in the .pdf at the end of the link to actually get there.

“I’m referring to the standard models of income determination.”

The ones that are completely wrong. They have no relevance. Why are you raising a straw man?

“Only under certain conditions does it produce a balanced budget.”

Yes that’s what I said originally. It’s time friction that causes a deficit. “Wait spending” if you like. That’s all it is – people who haven’t spent the money yet because they haven’t decided to for a myriad of reasons. Including they can’t find anything to buy – which is particularly relevant at the moment.

However the mechanical default is that you get a balanced budget because that’s how the maths works. The ‘hot potato’ position if you prefer. Which incidentally occurs at any positive tax rate since all a change in the tax rate does is change the number of transactions required to complete the spending chain.

And thereby defeating the mainstream “hot potato” fears since the sequence does complete.

Remember in MMT it’s the savings, stupid. That’s what causes all the problems.

Neil,

“The ones that are completely wrong. They have no relevance. Why are you raising a straw man? ”

Firstly, there is no straw man. Secondly, I have no problem with you formulating your own version of macro theory. Go for your life.

“Yes that’s what I said originally. ”

The conditions you are talking about and the conditions I am referring to are of an entirely different nature.

“Remember in MMT it’s the savings, stupid”

The standard model of income determination takes into account saving behaviour via the marginal propensity to consume.

Alright Neil. I hope you are paraphrasing something out of the Bill Clinton campaign when you say what you said there. And you should make that clear. Otherwise you are making a big mistake in your evaluations and just being rude also.

Sure, money from government spending will eventually be destroyed by taxes. But it isn’t like government waits until it is destroyed through taxes before spending again. Governments spend every day. Tax collection lags. MMT recognizes a government can spend too much in certain circumstances causing inflation. Tax collection does not necessarily keep pace with government spending as it increases.

“The conditions you are talking about and the conditions I am referring to are of an entirely different nature.”

But you responded to what I was saying – not the other way around. So shouldn’t the conditions you are talking about be the same as the ones I was talking about?

Otherwise we’re talking at cross purposes and not getting anywhere.

“Otherwise you are making a big mistake in your evaluations ”

Ok, I’ll bite. Where am I making a big mistake in my evaluations – using only what I have written above and not what you have (incorrectly) inferred.

“Tax collection does not necessarily keep pace with government spending as it increases.”

It does automatically as a matter of accounting, unless…

Neil,

I’m afraid I’m not interested in talking about your explanation because I believe it to be incorrect.

Neil,

Please explain the accounting.

“Which is why neoliberalism tries to push people into debt – so that everybody ends up like that person who is always broke on pay day. That’s their ideal condition. ”

It depends upon what YOU believe is neoliberalism?

“What is neoliberalism in simple terms?

Neoliberalism is a term for different social and economic ideas. … Neoliberalism is characterized by free market trade, deregulation of financial markets, individualisation, and the shift away from state welfare provision.”

‘They’ do not have an opinion one way or another re ‘pushing people into debt’. Rightly or wrongly, ‘they’ believe that it is up to the individual, who is aware of his/her own best interests, and will act accordingly.

‘They’ believe that the income/output of the economy is supply determined. The economy is ‘always’ at full employment. There is only ‘voluntary’ unemployment. Hence the arguments against ‘demand management’ and for ‘supply side policies’.

“‘They’ do not have an opinion one way or another re ‘pushing people into debt’.”

They do. That’s how interest rate targeting works. Hence the unseemly dash to hand out loans during the Covid crisis.

They might not say it explicitly, but that’s the operational result of pushing interest rates. For them to have any actual effect they have to push lending. Otherwise the control level has no ‘bite’ on the road.

Constantly falling interest rates is “too much saving” in their world remember.

“They do. That’s how interest rate targeting works. Hence the unseemly dash to hand out loans during the Covid crisis. ”

Then ‘they’ are not neoliberals.

@ Postkey,

I would say that anyone who believes cutting Govt spending and/or raising levels of taxation will necessarily lead to a reduction in the Govt’s deficit (regardless of whether we think this to be at all desirable) is a neoliberal.

Why apply a counter inflationary measure and expect anything else but a fall in levels of inflation?

The government, with its tool the central bank, can just create money whenever they see fit to do so. So there is really not “only so much saving to go around”. Ever. Unless you are already in a state of complete full and best possible employment of all resources. And past that point you see inflation.

I was referring to your use of the word ‘stupid’ Neil. That is the evaluation that is way off in this case. That is what was bothering me.

@ Jerry Brown,

Neil’s phrase was a variation of “It’s the economy, stupid”. It shouldn’t necessarily be taken to mean that anyone in particular has a low IQ!

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/It%27s_the_economy,_stupid

@Peter Martin:

My definition of “neoliberal”: anyone (like your side kick Gigi) who insists sovereign currency-issuing governments have to borrow (or tax) in order to spend.

Hence: the $130 billion rescue package is “borrowed money which must be repaid”, “it’s taxpayer money”, “the government’s money is our (private citizens’) money” etc etc etc.

All neoliberal brain-washing.

This is, essentially, professor R. A. Werner’s ‘take’.

“6. Bank credit creation for transactions that are part of GDP has been identified as the main

determinant of nominal GDP growth.24 Hence an increase in bank credit is required to boost

nominal GDP. By borrowing from banks, governments can pump-prime bank credit creation.

This boosts nominal GDP growth and hence domestic demand, resulting in greater employment,

lower expenditure on unemployment benefits, greater tax revenues and hence lower deficits

and also larger GDP, lowering the deficit/GDP and debt/GDP ratios by lowering the numerator

and increasing the denominator.”

And

“The deficit to GDP ratio will approach zero, as credit creation for GDP transactions boosts the denominator and increased tax revenues and reduced government expenditure reduce the deficit. In contrast to the unsustainable (explosive) deficit situation with bond issuance for government funding in case A, the new policy of not issuing bonds and borrowing from banks is sustainable and delivers the desired policy outcomes.”

Of course, it is assumed that a larger GDP is desirable, despite the concomitant negative externalities?

There is a wood – governments are monetary sovereign in their own fiat currency.

Then there are a lot of trees.

“This is, essentially, professor R. A. Werner’s ‘take’.”

(Sorry, I’m late to this party. I may have missed some context, though I’ve looked.)

The other part of Werner’s take is that government spending will only enter the GDP if the government borrows the money from a bank. Money that the government just spends will somehow not make it through.

This isn’t counterfactual, since borrowed money makes up about 97% of the M2 in advanced economies, but it mistakes an effect for a cause. It was a political decision, for example in Canada under Pierre Trudeau, to take provincial and municipal government borrowing away from the Bank of Canada, and route it through private banks instead. This was good for privae bank profits, problematic for the balance that the local governments had to maintain between spending and revenue (new interest charges draining revenue.)

With regard to the banking sector and the discussions above about people having accounts directly with the central bank and the TBTF nature of the private banks: Isn’t the simplest and best solution to nationalise them?! Then, yes, everybody could effectively have an account with the central bank. Lending decisions could then take into account more than short term profitability. Wider macroeconomic effects could be considered.

Let’s take the UK for example as that’s where I am. ‘UK Bank’ could be divided up into say (off the top of my head) six regional banks which would also help to address geographical disparities; if, for example, the housing market was over-heating in London but was cool in Northern Ireland, lending decisions could reflect that.

We’ve seen in the not-too-distant past where lending decisions being made purely on the short-term profit-motive gets us. And I’m not seeing us getting much more benefit from the competition between banks than we do from the ‘competition’ between energy companies.

Peter Martin @ 4:01, Thanks- I remember that campaign and eventually voted for Bill Clinton in it, and obviously mentioned it as a possibility. But I’m a 50+ year old American and this is a blog with readers of different ages and from many different countries that might not realize a reference to a US election from 28 years ago. That being said- I’m usually quite impressed with the readers of this blog and may have been underestimating that.

John Confidus @ 0:29. Hmn, that sounds familiar 🙂 There is a difference in what I said there in reply to someone else and what was going on in this thread. The statement that the US federal government could always pay off its ‘debt’ that was denominated in US Dollars, should it want to, is hard to contradict. What Neil Wilson said, well perhaps I don’t entirely understand it yet. But I think he was going to explain the accounting at some point. I will wait for that explanation.

“…and may have been underestimating that”.

You were, Jerry 🙂

@ John Lawless

Personally I think nationalising the banks is tangential to the TBTF problem. The banks in the role they *used* to perform before they went into the casino business – ie good old boring bowler-hat banking as someone once characterised it – were actually in the best position to assess credit-worthiness, back localised small businesses, etc, and generally provide a useful, targeted, credit-source whilst garnering steady but not spectacular profits for their shareholders in the process. I don’t see what’s gained by nationalising that, in fact I suspect it might be done worse not better.

The TBTF problem stems IMO solely (?) from the mega-banks’ stranglehold on the payments system as I already said. Each time there’s been an imminent threat of a a big bank going bust it has invariably been the risk (via a domino-effect) of the payment system grinding to a stop which has been cited as the reason why the govt can’t allow the failing bank to crash. When one remembers that for example the equivalent of the USA’s GDP passes through the payment system every six working days (!) the politicians’ panic is understandable.

If any citizen (and sole-proprietor business?) could take out her/his own account with the CB and thereby become enabled to conduct any or all money-transfers without even needing to have an account with any commercial bank that stranglehold would be reduced. Whether that would be enough is another question but I suggest itcwould be an important step in the right direction – as well as being a good thing for its own sake.

@ Neil Wilson

Sorry to prolong this, but in going back over your original reply to my mention of every citizen having his own account at the CB, I realised I’d failed to register what now strikes me as a potential paradigm shift in the public stance of any spokesman for core-MMT doctrine (which in my eyes at least you can most definitely be regarded as being) towards Positive Money.

(That’s not intended as in any way a challenge; I’m merely seeking clarity, not passing judgment).

“Likely the commercial banks will still act as ‘agent’, but if the bank went bust all that would happen is you would switch agent. The data records would stay the same. The format and logo on your statement would change.

“And that’s why the banks resist the change. Managing deposit and current accounts directly on their balance sheet makes it more difficult for the central bank to put them into administration if their loan book goes bad.

“Whereas if the central bank was the entire liability side of a commercial bank (as would be the case if entity deposits were moved to the Issue Department of the central bank), it could put the bank through administration any time it felt it was appropriate. The loss would then accrue to the central bank – as it should since they were supposed to be regulating the bank”.

If I understand that correctly (and I believe I do, except that I don’t understand the semantics of the distinction you seem to make between “deposit” and “current” accounts), it appears exactly in agreement with the position which Positive Money has taken up ever since its inception, the core of which is that commercial banks would be prohibited from taking deposit accounts (aka “demand deposits”, aka (American usage) “checking accounts”) onto their balance-sheets. That means that loans would NOT create (demand) deposits but loan accounts – which *would* of course be taken onto the lender’s balance-sheet (as a liability, with the borrower’s IOU as the counterpart asset).

Deposits of depositors *own* money (monthly salary-payments for instance) would be made into a “transaction account” which (though as in your suggestion administered by a bank, acting as an agent) would remain the personal property of the depositor and be held by the Central Bank as custodian.

Am I right in interpreting what you have written here as meaning exactly the same thing?

“The other part of Werner’s take is that government spending will only enter the GDP if the government borrows the money from a bank. Money that the government just spends will somehow not make it through.”

It will ‘make it through’: However, if not financed by borrowing from a bank or from the central bank, it will be offset by falls in other components of aggregate demand. This is because the velocity of the real circulation is relatively constant.

” . . . whereby the coefficient for ∆g is expected to be close to -1. In other words, given the amount of credit creation produced by the banking system and the central bank, an autonomous increase in government expenditure g must result in an equal reduction in private demand. If the government issues bonds to fund fiscal expenditure, private sector investors (such as life insurance companies) that purchase the bonds must withdraw purchasing power elsewhere from the economy. The same applies (more visibly) to tax-financed government spending. With unchanged credit creation, every yen in additional government spending reduces private sector activity by one yen. ”

“The empirical results for the Japanese case have been unambiguously supportive. The Japanese asset bubble of the 1980s was due to excess credit creation by banks for speculative purposes, largely in the real estate market. The apparent velocity decline is shown to be due to a rise in credit money employed for financial transactions, while the correctly defined velocity of the real circulation is found to be very stable”

As for favouring private credit creation, he is in favour of this as, bank credit creation for “transactions that are part of GDP has been identified as the main determinant of nominal GDP growth.”

He proposes a more democratically controlled private banking sector. ‘They’ will only be allowed to ‘create money’ for ‘productive purposes’.

Prof. R. A. Werner believes that the ‘wo/man-made problem’ was the issuing of the ‘wrong’ type of credit. There is ‘productive’ and ‘unproductive’ credit.

“Importantly for our disaggregated quantity equation, credit creation can be disaggregated, as we can obtain and analyse information about who obtains loans and what use they are put to. Sectoral loan data provide us with information about the direction of purchasing power – something deposit aggregates cannot tell us. By institutional analysis and the use of such disaggregated credit data it can be determined, at least approximately, what share of purchasing power is primarily spent on ‘real’ transactions that are part of GDP and which part is primarily used for financial transactions. Further, transactions contributing to GDP can be divided into ‘productive’ ones that have a lower risk, as they generate income streams to service them (they can thus be referred to as sustainable or productive), and those that do not increase productivity or the stock of goods and services. Data availability is dependent on central bank publication of such data. The identification of transactions that are part of GDP and those that are not is more straight-forward, simply following the NIA rules.”

Mefobills, on ‘another site’, pointed me in this direction.

“The Bank of Canada Should Be Reinstated To Its Original Mandated Purposes

John Ryan / March 21, 2018

The critical point is that between 1939 and 1974 the federal government borrowed extensively from its own central bank. That made its debt effectively interest-free, since the government owned the bank and got the benefit of any interest. As such Canada emerged from World War II and from all the extensive infrastructure and other expenditures with very little debt. But following 1974 came a dramatic change.

After its meeting with the international bankers’ Basel Committee in 1974, the federal government proceeded to borrow the bulk of its needed money, with interest charges, from private investors including banks and dramatically reduced dealing with its own bank that had no interest charges. This was done in secret and without the approval of parliament.”