These notes will serve as part of a briefing document that I will send off…

Why the financial markets are seeking an MMT understanding – Part 2

This is Part 2 (and final) in my discussion about what the financial markets might learn from gaining a Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) understanding. I noted in Part 1 – that the motivation in writing this series was the increased interest being shown by some of the large financial sector entities (investment banks, sovereign funds, etc) in MMT, which is manifesting in the growing speaking invitations I am receiving. This development tells me that our work is gaining traction despite the visceral, knee-jerk attacks from the populist academic type economists (Krugman, Summers, Rogoff, and all the rest that have jumped on their bandwagon) who are trying to save their reputations as their message becomes increasingly vapid. While accepting these invitations raises issues about motivation – they want to make money, I want to educate – these groups are influential in a number of ways. They help to set the pattern of investment (both in real and financial terms), they hire graduates and can thus influence the type of standards deemed acceptable, and they influence government policy. Through education one hopes that these influences help turn the tide away from narrow ‘Gordon Gekko’ type behaviour towards advancing a dialogue and policy structure that improves general well-being. I also hope that it will further create dissonance in the academic sphere to highlight the poverty (fake knowledge) of the mainstream macroeconomic orthodoxy.

There was an article in the Project Syndicate (July 1, 2019) – Does Japan Vindicate Modern Monetary Theory? – written by a Yale economics professor and advisor to Shinzo Abe, that reveals the extent to which the mainstream is becoming paranoid and is failing to understand what MMT is about.

I won’t deal with it in detail because it is not my brief today. But it aims to disabuse readers of the notion that “Japan … [is] … proof that the approach works.”

The approach he refers to is MMT.

Basic flaw. MMT is not an approach. These commentators haven’t even reached the first place in understanding what our work is about.

Mainstream economists have crudely characterised or framed MMT within their own conceptual structure (typically the so-called ‘government budget constraint’ (GBC) framework) and imputed their own language when discussing MMT.

The Project Syndicate author is no exception.

He thinks MMT is about “excessive deficit-financed spending” which “lacks any safeguard”.

He says:

Policymakers who recklessly implement MMT may find, like the sorcerer’s apprentice, that once the policies are set in motion, they will be difficult to stop.

One cannot “implement MMT” – recklessly or otherwise.

One can understand it and use its insights to craft policy interventions that accord with one’s value system (ideology).

The author invokes the image of the – Sorcerer’s Apprentice – a poem by Johann Goethe, to conjure up images of chaos and attempts to associate these images with our work.

But if he understood the poem and its historical context he would realise it is an extremely poor exampl to use.

Goethe, after all, was opposed to the French revolutionaries who overthrew the corrupt monarchy. He didn’t consider the former were capable. The poem in question was written around this time.

In Chapter 1 of the Communist Manifesto, we see a reference to the poem (implied) when Marx and Engels wrote:

Modern bourgeois society, with its relations of production, of exchange and of property, a society that has conjured up such gigantic means of production and of exchange, is like the sorcerer who is no longer able to control the powers of the nether world whom he has called up by his spells. For many a decade past the history of industry and commerce is but the history of the revolt of modern productive forces against modern conditions of production, against the property relations that are the conditions for the existence of the bourgeois and of its rule. It is enough to mention the commercial crises that by their periodical return put the existence of the entire bourgeois society on its trial, each time more threateningly.

The point is that Goethe was promoting the idea that the master has the wisdom to use his power effectively while the apprentice does not have that skill and should wait his time.

But if that master has failed – then the authority is gone.

Mainstream macroeconomics is not the master and MMT economists are not the apprentices.

The former deliver fake knowledge and all their incantantions cannot alter that fact.

I have made this point before but it is worth repeating because how we construct an argument (framing, concepts, language, etc) is incredibly important and influences how the argument is developed and received.

Mainstream economics starts with the flawed analogy between the household and the sovereign government such that any excess in government spending over taxation receipts has to be ‘financed’ in two ways: (a) by borrowing from the public; and/or (b) by ‘printing money’.

This framing therefore has three quite separate cases in relation to government spending:

1. Governments raise taxes which permit them to spend up to that level.

2. If governments want to spend beyond that level they have to find extra money.

(a) They can borrow the money from the non-government sector (issue debt) which pushes up interest rates (via the defunct loanable funds theory).

(b) They can instruct the central bank to print money and put it into circulation which is inflationary (via the defunct Quantity Theory of Money).

So there are three types of government spending with different impacts depending on the type chosen.

This characterisation is not remotely representative of what happens in the real world in terms of the operations that define transactions between the government and non-government sector.

The GBC framework entered the mainstream literature in the 1960s when it was claimed that government’s had the same constraints as households.

The basic analogy is flawed at its most elemental level. Households must work out the financing before it can spend – it has to earn income, run down savings, sell assets or borrow.

The household cannot spend first.

A currency-issuing government can (must) spend first and ultimately does not have to worry about financing such expenditure.

The mainstream economists see that statement and try to understand it within the flawed GBC framework.

So they interpret fiscal deficits as being typically damaging because they either drive up interest rates and ‘crowd out’ private spending that is sensitive to increases in interest rates or they become inflationary, depending on whether 2(a) or 2(b) is chosen.

And they might read somewhere that MMT economists point out that no debt needs to be issued to accompany a fiscal deficit and they frame that – because they construct everything fiscal within the GBC framework – as being about ‘printing money’.

Then, the GBC logic is applied and so MMT becomes a policy idea that wants the government to vicariously print money which automatically causes accelerating inflation because there will be “too much money chasing too few goods”!

Even the Project Syndicate author acknowledges that the massive fiscal deficits in Japan (and the fact the Bank of Japan has bought significant quantities of government debt) has:

… not generated a much-feared surge in inflation.

Note, the “much-feared” term.

However, he fails to interrogate that proposition in any way choosing to divert attention to a relatively meaningless and well-known fact that in Japan’s case there is a significant difference between gross and net public debt. So what?

Of course, reality is quite different to the way the GBC framework depicts the fiscal options.

There is only one type of government spending – where the relevant government body instructs a banker (usually a central banker) to credit some bank accounts. In some cases, cheques may be sent out but that practice is rapidly declining as the digital world expands its reach.

The inflation risk is embedded in the spending – how it impacts in goods and services markets.

And that risk isn’t particular to public spending. All spending carries the risk of setting of inflation.

In practice, many inflationary episodes have nothing to do with ‘spending’ surges. They arise from supply shocks or corrupt behaviour or cartel behaviour.

Issuing bonds to accompany fiscal deficits does not reduce the inflation risk. The bond purchases reflect an asset portfolio change – the funds were not being spent anyway.

If the bond holders subsequently use the income flows from the interest earned to increase, say, their consumption spending, then the government deficit will likely fall anyway due to the higher level of economic activity and rising tax flows.

If the higher level of activity threatens to push the economy beyond the inflation barrier then there are a series of choices the government can make, including reducing its deficit.

There is no sorcery involved. And no apprentices.

Further, the idea that ‘printing money’ is somehow an option is ridiculous. As noted above, all spending occurs in the same way – crediting bank accounts. No printers are involved.

It is interesting that the Project Syndicate author effectively, by his silence, does not seem to buy the ‘crowding out’ story. His sole focus is on the inflation story, however erroneous his depiction of that causality might be.

He claims that:

Implementing such a policy successfully, however, would demand careful attention to inflationary risks. The current deflationary phase will not last forever. Eventually, supply constraints will be reached, and inflation will return. If the government has been engaging in excessive deficit-financed spending, once inflation is triggered, it could quickly spin out of control.

It could although just to use the term “deficit-financed” is GBC language.

The point is that I would challenge the Project Syndicate author to show me where in the extensive MMT literature developed by the core group do we write or say anything that would say fiscal deficits cannot be excessive under some circumstances.

Here is a blog post that tells the MMT story exactly – The full employment fiscal deficit condition (April 13, 2011).

The widowmaker

The GBC framework is entrenched in the way economists think about fiscal policy impacts on financial markets and as the Project Syndicate article demonstrates is still resonant.

It is also clear that many players in the financial markets, who have probably been indoctrinated by mainstream macroeconomics programs in one way or another, have historically acted within that framework – to their detriment.

These are the characters that presumably lost in the famous ‘widow maker’ trade on Japanese government bonds.

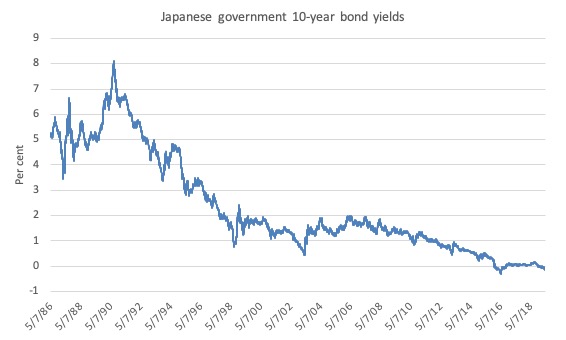

Here is the history of the 10-year Japanese government bonds from September 24, 1974 to June 28, 2019. On September 28, 1990, the yield on the 10-year bond peaked at 8.105 per cent.

The so-called ‘macro traders’ (those who decide their investment portfolios on the basis of macroeconomic principles and judgements about national politics) rushed in and ‘shorted’ the 10-year bond market.

Why? Because they had drank the ‘kool saké’ of mainstream macroeconomics and believed that the debt position in Japan was unsustainable and as a result yields would have to rise and bond prices fall.

So the short trade was to commit to selling these bonds at some future point in time and hoping at that point in time the spot price would have fallen below the future contract price thus eliciting a profit.

Variations of that theme were evident.

Any portfolio manager that bet on government debt yields rising in any systematic way lost a lot of money in the process.

On June 28, 2019, the 10-year bond was trading at -0.156 per cent, the 25-year at 0.302 per cent and the 40-year at 0.413 per cent.

As yourself what that means about expected inflation rates.

And then think about the fact that currently the Bank of Japan holds more than 40 per cent of Japanese government debt (as a result of its various QE programs) and has purchased most of the available issue since the Abe government came to power.

Mainstream economists consistently predict higher yields will emerge and higher inflation as a result of the Bank’s purchases, which pump reserves into the banking system in return for the debt purchases.

Chasing higher yields via these ‘widowmaker’ trades led to losses because the investment banks etc were engaged in a battle against the Bank of Japan, which is a battle they can never win.

An MMT understanding shows that the sovereign government (central bank and treasury) typically calls the shots over the financial markets.

It sets the rules, has the currency capacity to set yields and volume, and can stop issuing debt altogether if it chooses.

The financial markets are supplicants.

Lost opportunities

Last week, I read a briefing note from the Key Private Bank (June 24, 2019) – Modern Monetary Theory: What Should You Know?.

The Bank provides a range of banking services in the US including wealth management.

The short note seeks to:

… make the case for why investors should care about MMT and other potential stimulus measures.

It correctly distinguished MMT from “conventional thinking” (mainstream macroeconomics) where the latter thinks that:

… the ceiling on government spending is a function of tax revenues and the ability to issue debt at a reasonable interest rate.

In contrast, “(u)nder an MMT framework, government deficit spending is only constrained when it stokes unacceptable inflation”, which is sort of correct.

The correct constraint in MMT are the available real resources.

But I liked the term “an MMT framework” – reflecting the lens nature of MMT.

The author also notes that:

Another key difference of MMT compared with conventional economic thinking is that MMT emphasizes the fiscal authority (the federal government) and its ability to influence the economy, unemployment, and inflation versus the monetary authority (the Federal Reserve, or the Fed).

Now this might be conceived as a meagre difference between what the New Keynesian orthodoxy calls the ‘assignment’ problem – which policy tool to assign to what task.

However, our preference for fiscal policy is grounded in our rejection of the GBC literature. In addition, as a progressive MMTer, I object to anti-democratic processes – depoliticisation.

The important point that the Key Private Bank article makes is that:

MMT can provide unique insights into some unconventional policies that have been instituted after the Global Financial Crisis and in other countries such as Japan since the early 2000s. In 2010, many prominent economists were concerned that the Fed’s asset purchase programs (Quantitative Easing, or QE) would stoke currency debasement and inflation. Also, many investors avoided longer-maturity bonds at this time in fear of higher interest rates, and they raised their portfolios’ allocations to real assets that would benefit from higher inflation.

An MMT understanding would have told these investors that the mainstream economists (no matter how prominent they were) were plain wrong and that they would be foregoing profitable investment opportunities if they stayed within that orthodox economics framework.

They were wrong because their framework is wrong. Fake knowledge cannot systematically generate reliable predictions about reality.

It might hit targets occasionally, like a dead clock is correct twice a day! But it will systematically generate predictive errors.

Just look at the forecasting performance of the IMF models!

The Key Private Bank article says that:

With the advantage of hindsight, these fears were unfounded. The US dollar did not collapse, and inflation remained subdued. From an investment perspective, it proved costly to avoid longer-duration bonds and overweight real assets compared with emphasizing assets that benefit from lower inflation and a stronger dollar. An MMT perspective would have provided a different perspective of QE, viewing it as a debt-refinancing operation with limited impacts on inflation and the US dollar. This viewpoint would have been valuable at the time, and it is one potential benefit of understanding the MMT framework. It would have also provided a unique insight on the policies implemented in Japan and Europe.

Well it was available at the time and savvy investors took advantage of it.

The lesson that the Key Private Bank article takes from this is that there is a growing move to reduce reliance on monetary policy for counter-stabilisation and:

… authorities may look to fiscal stimulus that is partially financed by the Fed to increase economic growth.

In that context:

Wealth managers and investors should have a complete view of how this could work and what the potential costs and benefits could be.

The point of the article is that a more “complete view” will not come from mainstream economics. It is clear that MMT economics is a preferred framework to consider and analyse these trends and policy choices.

The Key Private Bank article advises wealth managers to eschew “politically driven views on what should happen”.

These are the views of the dominant paradigm in macroeconomics which make spurious predictions based on a flawed framework.

A Barron’s article (June 8, 2019) – Everything You Need to Know About Modern Monetary Theory – by Matthew C. Klein (behind a paywall) notes that:

The sharpest macro investors use these insights on a regular basis. Bridgewater Associates, by some measures the most successful hedge fund of all time, teaches them to its new recruits almost as soon as they walk in the door. Jan Hatzius, chief economist of Goldman Sachs … wrote in a recent client note, MMT “proponents make a couple of points that are both correct and important,” particularly the claim that “private sector deficits are generally more worrisome than public sector deficits.”

Investors armed with these insights knew the British pound would have to leave the European Exchange Rate Mechanism in 1992 and were among those who predicted the euro crisis that began in 2008. They avoided the infamous “widow maker” trade of betting against Japanese government bonds in the 1990s. Bridgewater and Goldman were among the few to realize the danger of rising U.S. household indebtedness during the 2000s, while remaining relatively sanguine about the federal budget deficit.

He notes that the likes of Paul Krugman took the opposite conclusions. For example, in 2003, Krugman “wrote in the New York Times that ‘skyrocketing budget deficits’ would force up interest rates.”

Further “many in finance and academia … [were] … scaremongers warning that “trillion-dollar deficits” and the Fed’s expanding balance sheet would lead to hyperinflation.”

It is clear that by holding out a series of myths as the path to ‘market efficiency’, mainstream macroeconomics leads to actions that actually generate market failure – as the GFC disaster demonstrated in spades.

Leading up to that disaster were all manner of self-congratulatory claims from mainstream economists that the economic cycle had been defeated, that financial market deregulation was delivering untold wealth – until it wasn’t and didn’t.

None of them saw it coming.

None of them saw the disaster that the Eurozone would become.

How much wealth was wiped out in the GFC is hard to assess but you can be sure it was concentrated at the lower end of the distribution.

Fiscal deficits mean more non-government net financial assets

One of the reasons the “sharpest macro investors” didn’t get sucked in by orthodox macroeconomics was that they understood the most basic aggregation in macroeconomics – the relationship between the government (as the currency-issuer) and the non-government (as the currency user).

This relationship is a core starting point for MMT reasoning.

The sectoral balances framework is not new. Nor was it invented, as some think, by British economist Wynne Godley. He certainly deployed it to great effect but the framework was articulated much earlier than his work.

Some of the older Keynesian macroeconomics textbooks from the 1960s and 1970s – contained insights into the sectoral balances – usually as a section in their derivation of the national accounts.

The work of German economist Wolfgang Stützel in the 1950s on – Balances Mechanics – can be considered a precursor to the modern stock-flow consistent reasoning.

After all, the sectoral balances are just a way of viewing the national accounts.

While more recently, the work of Wynne Godley has been important to establishing stock-flow consistency in macroeconomic models, using sectoral flows and their corresponding stocks to advantage, the MMT economists have taken that old framework one step further by distinguishing between vertical and horizontal transactions.

For basic Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) concepts, please read the following introductory suite of blog posts:

1. Deficit spending 101 – Part 1 (February 21, 2009).

2. Deficit spending 101 – Part 2 (February 23, 2009).

3. Deficit spending 101 – Part 3 (March 2, 2009).

Vertical transactions are those between the government sector and non-government sector and they are unique (different to horizontal transactions between entities within the non-government sector) because they alone create or destroy net financial assets in the non-government sector.

A bank loan creates a liability at the same time it creates an asset – nothing net is created.

However, the impacts of vertical transactions show the unique nature of the currency-issuing capacity of the government.

While the starting point – sectoral balances framework – is not new, the MMT perspective or interpretation and utilisation is novel.

What we learn from an MMT understanding is that:

1. A government deficit equals a non-government surplus – dollar-for-dollar. It is not an opinion but an accounting fact.

2. Such a deficit adds net financial assets (wealth) to the non-government sector. Deficits make us richer.

3. A government surplus equals a non-government deficit – dollar-for-dollar.

2. Such a surplus reduces the net financial assets (wealth) to the non-government sector. Surpluses destroy non-government wealth.

You will never learn that in a mainstream economics course. The mainstream economists can claim they knew MMT all along, or that there is nothing new, but you will never read those propositions in a mainstream textbook or hear them in a standard macroeconomics class.

Now that might not be a problem if those insights were trivial.

But, of course, they are not.

Some of the implications are extremely important.

For example, for a nation running a current account deficit (such as Australia – which has been in external deficit of around 3.5 per cent of GDP since the 1970s), the private domestic sector (households and firms) cannot accumulate net financial assets in the currency of issue if the government is running a surplus.

The only way the private domestic sector can save overall when the nation is running an external deficit if the government runs a fiscal deficit and adds net financial assets into the non-government sector.

The implication that then follows is that the only way the private domestic sector can maintain spending growth when the government is running fiscal surpluses is by relying on credit, which, in turn, leads to the increasing stocks of indebtedness and increasing vulnerability.

Ultimately, the balance sheet position of the private domestic sector deteriorates under these conditions to the point that they stop spending and attempt to reduce the precariousness of their balance sheets.

At that point, a recession occurs.

For Australia, the only way the conservative Howard government ran consecutive fiscal surpluses for 10 out of 11 years from 1996 was because household debt skyrocketed and reached unsustainable levels.

If the households had have maintained their historical saving behaviour, the economy would have soon tanked after the first or second year of fiscal drag and the surpluses would have vanished.

A further implication is that austerity become totally counterproductive if the non-government sector spending growth declines and private saving outstrips investment spending.

This desire to increase the non-government net saving requires increased fiscal deficits to avoid recession.

MMT economists have put all those linkages together.

Mainstream macroeconomics is too concentrated on making spurious claims about fiscal deficits – crowding out, inflation, debt burdens on future generations – that they fail to see the most basic role that fiscal policy plays in underpinning the desire to save overall and accumulate net financial assets by the non-government sector.

What can these insights mean for financial markets?

Matthew C. Klein writes that MMT shows:

… that investors cannot own financial assets unless issuers are willing to create them. Creditors cannot save unless debtors borrow. It is therefore impossible for everyone in the world to save by accumulating financial assets at the same time.

This means that corporate profits rise as companies invest, and fall as households, foreigners, and the government save … governments cannot cut their own debts without forcing others to save less or borrow more.

The point is that the smartest operators in the financial markets know this.

Only the less educated financial market players have bought the spin from the mainstream economists that ranges from deficits are typically not desirable to they should be avoided at all costs.

As a consequence, fiscal deficits actually provide more opportunities for financial market investment than surpluses.

This means that financial market operators should never be joining lobbies that proclaim the deficits are bad and should be avoided.

Quite the contrary.

Sovereign Funds

This leads to a consideration of so-called sovereign funds.

I wrote about the Australian version in this blog post – The Future Fund scandal (April 19, 2009).

The Future Fund was created by the Howard government which claimed it would ‘use’ the fiscal surpluses it was generating on the back of the household credit binge in the late 1990s to accumulate a stock of financial assets that would allow it to cover, in the first instance, the so-called ‘unfunded’ superannuation liabilities of public servants.

Its motivation was thus spurious at the outset.

It was claiming that the currency-issuing government would be unable to fund these liabilities as they came due because it would run out of money.

The terminology – Future Fund – was also unfortunate, given that the initiative ultimately undermines our future.

How so?

Essentially, the Future Fund was created using the net funds that were being extracted by the federal government from the non-government sector – spending less than they were taking out in taxation.

So after depriving the non-government sector of net financial assets, the government then used those funds to speculate in financial markets and accumulate financial assets themselves.

But at the same time it was overseeing chronic unemployment, rising underemployment, degenerating public infrastructure, declining educational standards, reduced service standards in the health system, and increased gridlock on our roads due to lack of planning.

At the time, the government could have used the net spending that they put into the Future Fund to offer a Job Guarantee position to all of the unemployed and underemployed for about the next decade at minimum wages.

When that option was presented, the response, among other disparaging remarks, was that there was no fiscal room to do any more on that front than they were doing at the time.

So we had a situation where our elected national government preferred to buy speculative financial assets instead of buying all the labour that is left idle by the private market. They prefer to hold bits of paper that has lost value than putting all this labour to work to develop communities and restore our natural environment.

They also preferred these bits of paper to improving our public infrastructure, making us the best performed education system in the world, reducing hospital queues, and improving public transport etc.

The point is that an MMT understanding shows that the currency-issuing government’s ability to make timely payment in its own currency is never numerically constrained by revenues from taxing and/or borrowing.

Therefore the purchase of a superannuation fund (in this case the Future Fund) in no way enhances the government’s ability to meet future obligations.

In fact, the entire concept of government pre-funding an unfunded liability in its currency of issue has no application whatsoever in the context of a flexible exchange rate and the modern monetary system.

The case of Norway, for example, is different. They are accumulating a sovereign fund because they are being flooded with external revenue from their North Sea energy assets.

They are running fiscal surpluses to ensure that the external revenue does not push the economy into an inflationary episode. At the same time the non-government sector enjoys first-class public services and infrastructure and can realise its overall saving targets without being compromised by the fiscal drag.

One might argue that the Norwegian fund is just an anti-inflationary device.

A more progressive Norwegian government might adopt the view that this surplus of income that the nation enjoys could be better diverted into foreign aid to help poorer nations achieve higher material standards of living rather than being use to buy ever increasing stocks of financial assets.

Ethical investment

Which leads to the final point.

I think the financial markets have the opportunity in the coming period to really change their entire mentality and become progressive leaders rather than parasitic takers.

It would be of great benefit if they channelled our net savings into ethical, green investments, perhaps taking a lower overall rate of financial return, as a trade-off for a massive positive social and environmental return.

Conclusion

I will report back after I have done a few of these workshops to let you know the reaction.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2019 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Massive ethical investment to save the rainforests by providing the peoples of the Equator with decent jobs so they don’t have to cut the trees to survive.

Gotta say, this is a brilliant blogpost. It’s the last of my regular reading today and I’m tired, but this was exhilarating. Always something new.

Is it really necessary to call them “parasitic takers” though? It doesn’t strike me as a very constructive approach toward further engagement with that sector.

The Norwegian sovereign wealth fund (like most other sovereign wealth funds) is not “just an anti-inflationary device”.

Rather the fund aims to achieve “the highest possible return with acceptable risk” for the long term benefit of the country.

.

Unlike superannuation funds like the Australian Future Fund, the Norwegian fund is not “government pre-funding of an unfunded liability in its currency of issue”. Nearly all of the Norwegian fund is invested in foreign assets. This means that it certainly does “enhance the government’s ability to meet future obligations”, which is its primary purpose.

See:

https://www.nbim.no/en/publications/reports/2017/annual-report-2017/

Being an corporate-economist (Ba) and working for many years in the financial sector and with i.e financial accounting the MMT theory was very easy to understand and acknowledge. The worst part of my university-studies in macro/micro-economics, in hindsight, was the total lack of knowledge of the monetary system and how banks works. Working in a bank later was a total eye-opener especially when learning how trade and clearing is done. A scandal that our american (chigago)economics literature only presented banks as lenders of existing deposits and not creaters of new deposits. Also of cource of the role of our central bank which was hardly mentioned in our literature 1986.

It must have been intentionally done if the same lack of education still exists!

Unlikely as it is, it would be deliciously ironic, and very telling, if parts of the financial sector end up taking the lead on the greening of industry that we certainly are not seeing coming from governments, who electioneering aside, currently behave more like anchors than propellers when it comes to moving on environmental matters .

In Canada, we saw the recent purchase of the Trans Mountain oil pipeline project by the Liberal government under prime Minister Justin Trudeau. Responding to my querying about this position, I received the following reply, (just the meaty part) from a Liberal MP:

“First and foremost, please rest assured that building new pipelines is something the greatly concerns me. That said, I understand that they are one of the few pollutants that bring money back into our country, and profits that are made can be used, among other things, to fund initiatives which enable us to phase out oil in the future. On that note, I am happy that the government recently announced that any revenue made by the pipeline will be earmarked for projects that will help with the transition away from fossil fuels to cleaner sources of energy. This project will also ensure that Canada is not dependent on selling its natural resources to the United States.

Something that may also be of interest to you is that Norway uses a similar energy model. Their $1 trillion government-owned investment fund redirects funds it has earned from oil and gas investments and places them in green energy products. In turn, this results in steady investments in renewable infrastructure for Norway.”

Thorleif, those Chicago charlatans never seemed to encourage anyone to ask how these banks could ever begin to loan out these deposits in the first place. Since they only loaned out deposits, how did they obtain their first one? With no central bank, it is as if their bank existed in the US wild west where there was no law either, a period that lasted only about 25 years. So, unless the owner(s) of this bank loaned out their own money that they had deposited beforehand, how would they encourage depositors who were not after loans to lodge their money in this bank? Guarantee the safety of their deposit against bank robbers? How? Provide interest? FDIC did not exist until well into the 20th century, so this was insecure. This story hangs together only under the most unusual circumstances, not unlike hyperinflation scenarios.

And in the period in which they initially developed this story, the mid-30s, there was a central bank and loanable funds were nonexistent. How they convinced themselves to believe this rubbish, if they ever did, is beyond me.

Stützel may have preceded Godley but his diagrams are not that accessible. Moreover, his two books, the one on paradoxes and the other on balance mechanics do not seem to be available, even in German.

The author you first mention, Hamada, begins by cleverly mentioning AOC and Jamie Galbraith and then segues into a mention of Rogoff, he of the spreadsheet error, in the context of MMT being problematic or even dangerous. And who does he link to for support for this dangerousness claim? A Sebastian Edwards. Who he? You may well ask. He is an international economist at UCLA’s graduate management school. He is also the author of American Default: The Untold Story of FDR, the Supreme Court, and the Battle over Gold published in 2018. His thesis here is that when FDR took the US off the gold standard, the effect was to devalue the dollar which, to Edwards, amounted to a default. The banks fought FDR tooth and nail. So did Hoover, the deposed president. And so did the rich, who tried, unsuccessfully, to engineer a military putsch. At no time in this period am I aware that the US ‘defaulted’ on any debt.

The bankers thought FDR waS

Stützel may have preceded Godley but his diagrams are not that accessible. Moreover, his two books, the one on paradoxes and the other on balance mechanics do not seem to be available, even in German.

The author you first mention, Hamada, begins by cleverly mentioning AOC and Jamie Galbraith and then segues into a mention of Rogoff, he of the spreadsheet error, in the context of MMT being problematic or even dangerous. And who does he link to for support for this dangerousness claim? A Sebastian Edwards. Who he? You may well ask. He is an international economist at UCLA’s graduate management school. He is also the author of American Default: The Untold Story of FDR, the Supreme Court, and the Battle over Gold published in 2018. His thesis here is that when FDR took the US off the gold standard, the effect was to devalue the dollar which, to Edwards, amounted to a default. The banks fought FDR tooth and nail. So did Hoover, the deposed president. And so did the rich, who tried, unsuccessfully, to engineer a military putsch. At no time in this period am I aware that the US ‘defaulted’ on any debt.

The bankers thought FDR was stealing from them, the rich thought he was destroying capitalism and introducing some kind of socialism (as did Hoover), though what FDR really did was to save capitalism from itself. One message that can be taken from FDR’s experiment is that unregulated capitalism is unstable, at the very least.

Does the sentence “This means that corporate profits rise as companies invest …” quoted from M. C. Klein’s report and approved of by Bill mean that private consumtion is irrelevant to corporate profits? I wonder.

Allan using and controlling current and future goods and services without providing

anyone else with goods and resources seems like parasitic behaviour to me.

Kingsley, on the subject of Norway’s sovereign wealth fund, you write: “it certainly does “enhance the government’s ability to meet future obligations”.

Bearing in mind that the government’s capacity to issue kroner is unlimited, could you explain the workings of the enhancement mechanism that you are certain about.

So I’ve been thinking of ‘sovereign wealth funds’ and what their supposed purpose is and how they fit into the way I understand the economy now that I have some understanding of MMT. And I am confused and these are my various confused thoughts and questions.

Leaving the external sector out of it completely- a government that runs a ‘budget surplus’ but then spends that ‘surplus’ buying assets from the private sector cant really be running a surplus right? It’s actually spending into the private sector just as much as it is taking away in taxes. The spending just happens to be directed towards the previous owners of the assets being purchased by the government. Which is probably good for those owners (or they wouldn’t sell), and for all the owners of similar assets if it increased the price of them?

Assuming the sovereign wealth fund buys equity shares in private domestic businesses in order to obtain a future income stream from a share of the profits, what does that do that is any different for the government? From the MMT perspective it wouldn’t seem to drive demand for the currency like taxes do, it probably even decreases that demand. And what real use to the government is an income in the currency (that the government issues at will) anyway? It doesn’t give the government any more ability to spend than it already had. And I don’t see that it would increase the production of real goods.

Would it make a difference if the government received a percentage of the firm’s real output rather than a percentage of its monetary profit? I’m not understanding how any of it could be called an anti inflation device.

If a government’s ‘wealth fund’ purchases foreign assets, how can it expect to enforce any claims to future payments based on that ownership? Threat of war? Norway probably doesn’t scare China or the US or anyone else all that much. I doubt Australia does either. Which isn’t a bad thing. Not being scary seems better than forever threatening to destroy things and people. Dead people don’t make the things anyone wants anyway. They are not usually all that productive.

@ Alan,

IStM that Norway can’t even sell those foreign assets [in its fund in a time in the future when it has no more oil to sell and so is deficit spending] when inflation is starting, to spend into the national economy that isn’t paid for by just more deficit spending.

This is because all spending is inflationary. It doesn’t matter where the money came from spending it is inflationary and will make a beginning inflationary period worse.

.

On that other site I spoke about, I pointed out that Japan “proves” that massive deficit spending doesn’t always cause too much inflation because over th last almost 30 years Japan had done that and inflation has not gone above 1% [or so].

One of the knowledgeable on economics guys is trying to argue that Japan does not prove this because over that same period of time the yen has gone up in value on the international currency market. And this off-set the inflation that would otherwise have occurred.

. . I argued back that it isn’t clear to me that the 2 markets are really one market. The 2 markets being the international market and the local national Japanese market. [I didn’t claim that the international currency market is not a goods and services market.] Anyway he doubled down and [to me] just reasserted his initial claim without any reasoning for why the 2 markets are one market. I replied that ‘to me he had just restated his position. He has not replied yet.

. . However, in my last reply to him I added at the bottom that I see a contradiction between a rising yen for 30 years in a time of *large* Japanese deficit spending and the MS economist’s claim that deficit spending will always have the effect of making “money people” try to stay away from that currency. Again, he has not replied yet.

Am I making any sense here or am I just lost in the weeds?

Off topic.

During WWII the US Gov. built [paid to have corps. build] special factories to make B-24 bombers and separately B-29 bombers. Those factories were very efficient and built a lot of bombers. At the end of the war the US had a lot of mostly useless bombers.

That was then, and this is now. Then the world needed more big bombers, now it needs more solar panels.

What would be the economic effect if the US Gov. built [with money for a GND] efficient factories to make *huge* numbers of solar panels and gave them to 3rd world nations and sold them at cost [or whatever less the market would pay] to everyone else? Note that here I mean to cut out all corps. and have the Gov. do this directly.

Any thoughts?

.

Given this assertion, which I accept:

“One can understand [MMT] and use its insights to craft policy interventions that accord with one’s value system (ideology).”

And given that most post-60s Australian, USA, UK governments (on both “sides” of politics) have had beneath their neo-liberal rhetoric, a determined agenda to benefit the large donors and friends to their ruling parties. (i.e. resources & fossil fuels, banks & financial sector, tobacco and alcohol, developers, Big Pharma, livestock and dairy) even with an MMT understanding of how money works, what’s to say future governments would not invest in infrastructure that primarily benefits the owners of sectors that have deeply anti-social or anti-environmental impacts by definition, and increases inequity around the world as the catastrophic impacts of the climate emergency start rolling in on a timetable with exponential increases in human suffering and national security disruption?

Can someone please explain to me the “much feared surge in inflation”?

Much feared by whom? Certainly not by those who own very little, since they have almost no securities denominated in the inflating currency, and therefore virtually nothing to lose.

I suspect the answer is that those who fear inflation are those who are already rich, since their assets are likely constituted primarily of debt instruments, and inflation favours debtors, not creditors.

@ eg,

Much feared by MS economists and those who listen to MS economists.

The really rich have most of the wealth s owning comp., like google.

The merely rich have their wealth in stocks, real estate, and bonds.

But, you’re right IStM that MS economists say this to scare the people into letting the Neo-liberal theory win in Gov. policy making.

The bottom half should not worry that much, unless they fear that their wages will not keep up with inflation. Which can be a real fear.

The guy on that other site replied. This is his reply.

“There’s no contradiction” [between claims that deficit spending always will lead money people staying away from that currency and the fact that despite large deficits for 27 yr. The Japanese yen has been bid up to record highs] “because economics is complex. Economists often construct models by freezing variables so as to construct theoretically testable cases for their thought experiments. When analyzing real-world cases it is necessary to consider the multitude of factors.

Japan has sought to pursue inflation-based growth, and inflation-based export stimulation, but the policy has been only partially effectual. It may be primarily the result of the actions of the ‘money people’, but there are other potential factors, such as the relative movements of foreign currencies, the domestic price movements in Japan (which could be owing to various factors, including weakening domestic consumption and cost-saving domestic production methods), input prices, the ineffectualness of Japan’s monetary policy, etc. Among these, weakening domestic consumption, ineffectual monetary policy, and indeed the actions of the ‘money people’ are all seemingly present at the surface level.

So to return to my original (and basic) point, the case of Japan is not a ‘proof’ of anything really, given the complexities. Japan has been suffering from weak growth for going on 30 years, and this is sort of the background to everything else.

Demographics also has something to do with it, Japan’s population is aging and shrinking.

If anything Japan demonstrates a failure of monetary expansion as a means of growth.

The function of debt for a government is supposed to be like that of a business, which borrows to expand production. In Japan it hasn’t worked out exactly, but the government is still left with the debt. Over the long term debt can be an inhibitor of growth. Hence in Japan they have also been using austerity, including proposals to reduce pension payments, etc. Austerity is the opposite of fiscal-led expansion, and reducing transfer payments and other government spending inhibits aggregate demand and hence economic growth.

As such Japan is a superficial example, which does not withstand scrutiny.”

.

Anyone want to make a comment on my point and his reply?

I see my fears about Bill’s recent talks with big finance guys were due to my ignorance about his ulterior missionary motives:

“Ethical investment

Which leads to the final point.

I think the financial markets have the opportunity in the coming period to really change their entire mentality and become progressive leaders rather than parasitic takers.

It would be of great benefit if they channelled our net savings into ethical, green investments, perhaps taking a lower overall rate of financial return, as a trade-off for a massive positive social and environmental return.”

As a (non-practicing, non-believing and rather hyper-critical) catholic, I will lead the push for your canonization as “Saint William of Melbourne” if you were to succeed in converting enough of those financial parasites to get the snowball rolling. After all, this would be a far more impressing feat than being pierced by arrows, bleeding out of the palm of your hands for no apparent reason or any of that other nonsense.

“Thou shalt mind the difference ‘tween thy household and the sovereign of currency in thy land and from hence forth thy analysis shalt be consistent with the gospel of stocks and flows.”

I might even go to church again for that. Keep on preaching!

Cheers!

@ Allan and Steve American,

The Norwegian government’s ability to issue krone and the Norwegian inflation rate have no direct relevance to the value of the sovereign wealth fund valued in foreign currency.

When needs arise in the future, the fund’s assets could be sold for $. The $ proceeds could be:

– used by the government for direct purchases of imports of goods and services (or for foreign aid);

– used by the government/central bank to purchase krone on the foreign exchanges, thereby increasing the exchange rate. This would make imports cheaper for Norwegians and raising their living standards. Demand for import substitutes and exports would be reduced freeing resources for other purposes (extra government spending and/or private consumption/tax cuts).

.

@ Jerry,

I agree that there is no certainty of returns from any investment. I should have written:

Nearly all of the Norwegian fund is invested in foreign assets. This means that there is a good prospect that it will “enhance the government’s ability to meet future obligations”, which is its primary purpose.

Charts in the Annual Report show that value of the fund continued to rise even through the GFC.

.

The Funds management is plainly aware of risks. In the Annual Report they write:

“Our role is to manage the wealth in the fund for future generations. We seek to safeguard the fund’s international purchasing power by generating a real return over time that exceeds growth in the global economy. The fund is to be invested in most markets, countries and currencies to achieve broad exposure to global economic growth.”

@Steve A:

That is a long and convoluted way of him to concede he has no good explanation for his position.

“The function of debt for a government is supposed to be like that of a business, which borrows to expand production.”

Just plain wrong. A business needs to aquire capital before (it) invests. A government doesn’t, it simply spends. Issuing debt is optional and voluntary for currency sovereigns. This point is very weak, but consistent with mainstream thinking.

“In Japan it hasn’t worked out exactly, but the government is still left with the debt. Over the long term debt can be an inhibitor of growth.”

“Can” be? When exactly? How long is the long term and how high is a high debt? The “best” case study for the mainstream view to my knowledge was the Reinhart & Rogoff perennial work of cherry-picking and conflating causation and correlation. Simply look at countries with low growth and a high debt2gdp-ratio and declare yourself the winner, while…

“As such Japan is a superficial example, which does not withstand scrutiny.”

…you ignore any country that doesn’t follow your rule or rule it an “anomaly”. In short, you fit reality to your model and not the other way around.

All the while ignoring that Japan has had to “endure” looking at a red number on a spread-sheet where it says “deficit” for years and all it has to show for is a technologically advanced nation with state of the art services for nearly all it’s citizens, an extremely low unemployment and a stable (albeit a little too low) inflation rate and the highest life expectancy of the world. Sign me up for some sweet Japan-style deficit please!

It’s a bit ironic that the Japanese themselves “dont’ get it”, as bill pointed out recently, and every time they start listening to the shrills again and engage in austerity measures a crisis looms.

When I read the reply of that guy I had to think of the “Gish Gallop” approach to a debate. Highly effective, but intellectually (and morally) bankrupt.

Cheers!

I understand how a fiscal surplus can be a valuable anti-inflation device in the context of a roaring current account surplus that is at risk of overheating the domestic private sector.

However, what I don’t understand is how a fiscal surplus can be used to buy assets for a sovereign wealth fund. I thought that a fiscal surplus is a net deletion of non-government financial assets. If the government purchases non-government financial assets to the value of its fiscal surplus, isn’t it undoing its surplus? Isn’t it injecting its currency into the non-government sector?

@Steve,

I’m not good at arguments, but he basically admitted a) he has no actual model of how anything works, since it’s too complex, and relies on ad-hoc models that start with the conclusion, as bill often criticizes; b) Japan should really expand more to hit its inflation targets.

He’s right that Japan doesn’t prove anything, it’s one datapoint, and of half-assed policy at that. But it’s also one more datapoint in decades of economic policies in the whole world that all add up to prove that monetarism is pure fiction.

To all who replied,

thank you.

You-all confirmed my thinking.

But, he doesn’t buy all of MMT and we do. So, of course, I think like you.

Does any one agree that there is a contradiction. For 27 years Japan has had a large deficit & its natl’debt is 240% of GDP, and yet international money people have bid up the yen to record highs. [I’m guessing on the ‘record’ part.]

Aren’t those money people supposed to avoid the yen, not flock to it?

To all who replied,

thank you.

You-all confirmed my thinking.

But, he doesn’t buy all of MMT and we do. So, of course, I think like you.

Does any one agree that there is a contradiction. For 27 years Japan has had a large deficit & its natl’ debt is 240% of GDP, and yet international money people have bid up the yen to record highs. [I’m guessing on the ‘record’ part.]

Aren’t those money people supposed to avoid the yen, not flock to it?

Steve,

Just want to say that most of the yen-trade is done “internally” by corporations, instituitions and banks incl BoJ. Government debt owned by non-japanese is maybe around 10% only. BoJ has now long term been selling currency-reserves for yen during its ABE-reforms to stimulate growth and inflation. Yen has also been currency of pref during financial instability (i.e when japs are taking money back home).

Otherwise I agree to you views regarding the yen strength relatve to debt-ratio. Is has also been interesting to see how japanese gnp/capita have been exceeding major western countries.

Best regards

Correction: It should be gdp/capita, not gnp!

@Thorleif,

I don’t think that internal trading of the yen will effect the international value of the yen.

Unless it is to and from foreign currencies.

You wrote, “It has also been interesting to see how Japanese gdp/capita have been exceeding major western countries.”

Major European nations have seen austerity and slow GDP growth since 2008 and the US has seen bubbles in stock and housing prices and this has to some extent inflated its GDP.

. . . OTOH, Japan’s housing prices have also risen and raised its GDP.

@ Alastair Leith

Wednesday, July 3, 2019 at 12:53

“Given this assertion, which I accept…”

“… And given that …” etc

“… what’s to say future governments would not …” etc?

Nothing at all IMO. But are you only offering a council of despair?

Isn’t it conceivable that “future governments” might be compelled by their electorates to behave in a radically more enlightened and far-seeing way? The past isn’t necessarily always (or ever?) a reliable guide to the future. And it’s certainly never a *complete* one.