I grew up in a society where collective will was at the forefront and it…

Donald Trump’s tariff hikes are not good policy

I am generally not in favour of trade protection. I grew up in a country that had very extensive protection (tariffs, import quotas) on manufacturing goods, which was justified on a number of grounds – capacity to shift to defense industries; stable employment; and more abstractly, an expression of becoming a ‘modern’ nation, leaving our agrarian roots behind. The initial move to impose high tariffs was that a young industry would take time to develop – the so-called infant industry argument, which goes back to the 1790 Report on Manufactures written by American economist Alexander Hamilton. The problem is that the infant never really grew up and the tariffs just became a cosy rent-sharing margin for unions and multinational corporations. Meanwhile consumers paid excessive prices for deficient-quality motor vehicles (among other products). It is clear that as trade opens up there are workers and regions that lose – and lose badly. The answer is not try to reinvent the past through protection. Rather, it is to use the government’s fiscal capacity to create new opportunities in these regions to ensure that workers disadvantaged by import competition can transit into new jobs with stable incomes. That option is often overlooked because modern governments have become obsessed with austerity. And, as I argue below, that obsession will in the context of Donald Trump’s tariff hikes, work against the European nations that are running ridiculously large current account surpluses.

I last considered the trade argument in this three part series:

1. The case against free trade – Part 1 (October 27, 2016)

2. The case against free trade – Part 2 (November 8, 2016)

3. The case against free trade – Part 3 (November 22, 2016).

What we learned in that series was that:

1. Early theoretical attempts (for example, Heckscher-Ohlin theorem) to justify so-called free trade (absence of protection) were shown to be flawed.

2. More recent developments in trade theory – the so-called ‘New Trade Theory’ in the 1980s – meant that economists could no longer argue that the results of the free-trade models held.

3. This shift in economic theory away from a blind acceptance of a proposition that free trade was always good, is quite apart from other considerations, which we might categorise under ‘fair trade’ issues.

4. When ‘free traders’ talk about the ‘free market’ and appeal to the narratives that appear in undergraduate economics textbooks they are being deceptive. No corporate leader aims to achieve that state. At a minimum, they aim to manipulate the ‘market’ they trade into to influence prices they can get and have to pay for inputs and end up with as big a margin on total costs as they can achieve.

They aim to create a unique product and drive competitors out of business as quickly as they can. If they can take over a competitor and increase their market share they will.

They seek to manipulate consumers into believing their product is best through advertising, which uses psychological tools that go well beyond the textbook idea that such interaction with the ‘market’ is just to provide ‘information’.

5. The 2007 book by Ha-Joon Chang (The Myth of Free Trade and the Secret History of Capitalism) demonstrates that the normal model of economic development, which has enriched the advanced nations such as Britain and the US, was not built on a ‘free trade’ platform.

Rather, they developed into rich nations through the use of industrial protection and government controls and supports.

None of the advanced nations would have achieved that status if they followed the IMF/World Bank approach.

6. The problem with the ‘infant industry’ justification is that the tariff wall provides a perfect environment for rent-seeking – so that the recipients of the protection have little incentive to innovate and become more competitive without the support.

The case of the Australia motor car industry is a classic example. The foreign-owned corporations profited from the tariffs and to avoid industrial unrest ‘shared’ some of the tariff benefits with the unions in the form of higher wages.

But by the 1970s despite effective protection rising, total employment was falling such was the competitive gains being made by Asian car manufacturers (Japanese initially) as the local industry failed to innovate.

In other words, the ‘baby never grew up’. Too many companies set up to exploit the tariff and too many models were produced for a market that could barely support one manufacturer producing at lowest-cost scale.

The level of protection was so high that it was estimated in 1985 that it would have been cheaper for the government to give all the workers in the Australia car building industry $A1 million each and close the industry (Source).

7. Rich nations such as the US and the European Union still maintain a complex array of tariffs on goods attempting to enter its borders. Japan, for example, maintains a highly protectionist stance with respect to its primary products (particularly against rice imports). These cases are generalised across most nations.

So when you read commentators, particularly Europeans railing against Donald Trump’s new tariffs on steel and aluminium (the precursor, probably to widening into cars), you have to realise that the protection levels in the EU are, on average, higher than they are in the US and many other advanced nations.

EU is not in a position to make trade threats …

When Donald Trump made his announcements, the bumbling European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker immediately announced that the EU would increase tariffs on “Harley-Davidsons, Kentucky bourbon and bluejeans” in retaliation (Source).

This was after Trump has tweeted that “trade wars are good, and easy to win”.

On March 3, 2018, Trump clarified his position and said that the US would “soon be starting RECIPROCAL TAXES so that we will charge the same thing as they charge us”.

When assessing what the likelihood that the European nations will retaliate against the Trump moves one has to understand what is at stake on both sides.

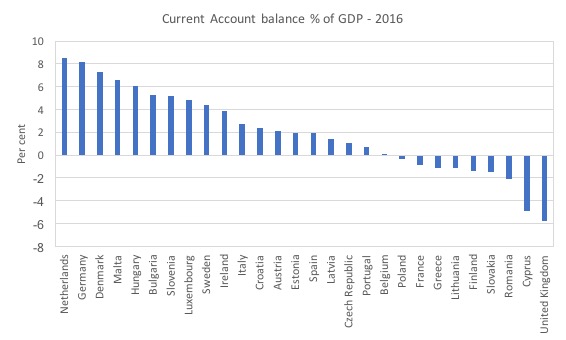

Behind the EU tariff wall, we see Germany running massive trade surpluses of around 8 per cent of GDP, although the Netherlands is even higher (8.5 per cent of GDP in 2016).

The Eurozone current account surplus in 2017 was around 3.5 per cent of GDP. It is not just a ‘German’ problem.

The overall European mantra is to fete these massive trade surpluses and to implement domestic policies that suppress imports. Citizens seem to have dulled into the idea that selling off national real resources and denying the citizens access to them is smart policy.

And if the citizens then decide they want to purchase more from outside (imports) the policy bias is to crush that spending capacity with austerity.

It doesn’t make any sense.

In many of the Eurozone Member State cases, the shift in trade balances towards higher surpluses has not come from a boom in exports but rather from a suppression of imports as a result of the austerity.

The following graph shows the Current Account balances for the EU nations as at 2016. They haven’t changed dramatically since then.

By deliberately suppressing domestic demand and relying on exports for growth, the EU nations, particularly the Eurozone Member States are trying to ride off the back of import spending of other nations – particularly, the US, Japan, China and the UK.

And, then they complain that these nations seek to redress that imbalance.

Which suggests that in both the Brexit negotiations and the EU response to Trump, the EU is in the weaker position.

Germany’s four major exports are (Source):

1. Motor vehicles, trailers and semi-trailers – 234,387 million euros or 18.3 per cent of total.

2. Machinery and equipment n.e.c – 110,519 million euros or 14.4 per cent of total.

3. Chemicals and chemical products – 114,661 million euros or 9.0 per cent of total.

4. Computer, electronic and optical products – 110,519 million euros or 8.6 per cent of total.

In terms of where the exports go and imports come from for Germany, the following table shows the “Ranking of Germany’s trading partners in Foreign Trade” in terms of the Foreign Trade Balance in Euro 000s down to the 36th largest surplus.

For the – Complete publication.

US and the UK!

When the whole policy strategy (trade surpluses and domestic demand suppression) is so dependent on a few nations playing ball, who do you think is in the driver’s seat.

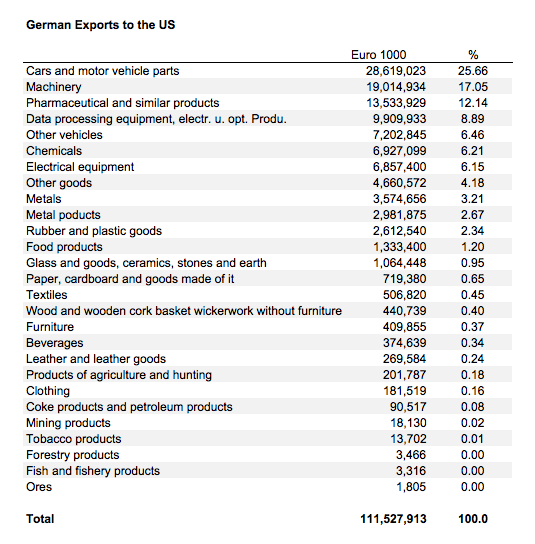

While the US is Germany’s largest steel export market, its major exports to the US (as shown in the Table that follows) are Cars, Machinery and Pharmaceuticals.

If the EU was to start threatening US imports such as Harleys then you can imagine what Donald Trump would do next – increase the tariffs on “Cars and motor vehicle part” and “Other vehicles”, which comprise 32 per cent of Germany’s total exports to the US and would go a long way to shutting down the Current Account surplus it runs against the US.

So the Juncker threats are hollow.

The same applies to the Brexit negotiations in my view. Britain has the balance of the bargaining power in those negotiations if it only had to stamina to use it.

In other words, the big German car manufacturers will not sit idly by while the German government or the European Commission plays out a ‘trade war’ with the US (or Britain for that matter).

The German car industry has not yet dealt with its massive fraudulent behaviour with respect to emissions. Cleaning that mess up (sorry for the pun) will be destabilising enough.

While Germany holds itself out as a sophisticated and efficient trading nation, its growth strategy is, in fact, rather crude.

Wolfgang Münchau’s latest Financial Times article (March 18, 2018) – In a trade war Germany is the weakest link – makes two really apposite points here.

1. “the ongoing collapse in the sale of diesel cars”, which the “German car industry placed a heavy bet on” and “invested in the wrong technologies for too long”, is a major threat to the German export machine.

2. “it is utter madness for the EU to have allowed itself to become so dependent on the export of a late-lifecycle product. Its entire business model turns out to have been based on the bet that Mr Trump would not become US president, that there would be no Brexit, and that you could cheat on emissions targets forever.”

So both Germany and the EU in general have been pursuing a rather myopic strategy which is vulnerable to responses like those outlined by Donald Trump.

The myopia lies in the fact that Britain and the US have become too important to the EU trade machine for them to be disregarded. Their concerns will have to be dealt with and in a way that is favourable to both nations.

As Wolfgang Münchau wrote:

… EU leaders are in a weak position and have relied for far too long on the US for its external security and, more recently, as the absorber of its structural current account surpluses. With his trade tariffs, Mr Trump has a single instrument to influence both the EU’s trade policy, and the defence spending targets of member states and their contributions to Nato.

One could argue that it is immoral to use trade policy in this way. But that argument loses force if you consider the morality of the EU’s policy to run a large and persistent surplus with the rest of the world. Or indeed of making defence spending promises they had no intention of keeping.

What is also obvious is that nations such as the Netherlands, Germany, and Denmark to name just a few European Union members running ridiculously large current account surpluses have the capacity to reduce trade tensions without resorting to defensive tariff responses.

Their massive trade surpluses result not only from the quality and attractiveness of their exports, but, also from their perverted domestic policies which have included suppression of wages growth and cutting purchasing power of pensioners and others.

To truly become global citizens these nations could abandon (or even relax) the austerity bias by stimulating domestic demand through improved wages and increases in the minimum wage.

That would help the beleaguered workers, especially those on low-pay.

Imports, including from the US and the UK would rise, which would help reduce the trade imbalances against the US and other advanced nations.

Does that mean Trump’s tariff increases are desirable?

All of the above should not be taken as an approval of Donald Trump’s approach to creating jobs in the US.

There is no ambiguity in the result that economists have known about for decades – that reducing tariffs hurts particular segments of the workforce.

Dani Rodrick has just published an interesting article in the Journal of International Business (December 8, 2017) – Populism and the economics of globalization – which argues that:

… low-skilled workers are unambiguously worse off as a result of trade liberalization … trade generically produces losers … redistribution is the flip side of the gains from trade. No pain, no gain …

Economists know this but are usually relatively silent on the losses while spruiking the gains from trade.

Dani Rodrick summarises literature that researched the gains from the introduction of NAFTA. He notes that the research found that:

NAFTA produced modest effects for most US workers, but an ‘important minority’ suffered substantial income losses … the effect was greatest for blue-collar workers: a high-school dropout in heavily NAFTA-impacted locales had eight percentage points slower wage growth over 1990-2000 compared with a similar worker not affected by NAFTA trade … wage growth in the most protected industries that lost their protection fell 17 percentage points relative to industries that were unprotected initially.

Those impacts are not trivial, “especially when one bears in mind that the efficiency gains generated by NAFTA apparently have been tiny.”

In that light, I thought this Deutsche Welle article (March 17, 2018) – German, French far-right voters felt abandoned, study finds – was pertinent.

The evidence is that:

Sociopolitical conditions and not anti-foreigner views drove discontent, the think tank found in its survey of regions where the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) and France’s National Front (FN) often scored in excess of 20 percent in last year’s elections …

Low wages and the collapse of social and transport infrastructure are the real drivers of anxiety about the future … feeling of being abandoned …

This is the environment that Donald Trump is now making waves within.

The problem is that, in my view, they are the wrong waves.

First, tariffs punish local consumers and do not necessarily lead to gains for local workers.

Australia’s case suggests that the tariffs create massive ‘rents’ that could be divided up between powerful multinational companies and unions but did not necessarily protect employment.

But the consumers of the protected products paid multiples over what the imported item would cost net of the tariff (the car tariff in Australia was at times over 50 per cent) and, as a result of the lack of innovation, had to put up with inferior products.

The joke in Australia in the early 1970s, before the imported market really started opening up, was that you could park an Australian-made car on the crest of a hill and the front and back of the car would sag according to the slope. They were bombs without adequate heating or radios, primitive comfort and unreliable performance.

The question then is even if the tariff protects a specific group of workers is that preferable to punishing all consumers via higher prices and inferior goods (especially when the workers being protected are punished as consumers as well?

It is obvious that reducing tariffs hurts the workers directly competing against the specific imports while it typically benefits the overall consumer.

Lower prices is preferable than higher prices for workers.

While the tariff hike threat might damage the EU nations, which might stimulate them to end their ridiculous mercantalist policy approach, the policy shift is unlikely to help American workers, particularly low-income communities.

The solution then is not to think the jobs that are disappearing due to trade with other nations can be protected or, indeed, once lost, regained.

I cannot see the steel belt industrial regions of the US become a global powerhouse again.

The secret is for governments to realise they have the fiscal capacity to introduce appropriate transitional adjustments.

In these blog posts – Australia’s response to climate change gets worse (November 15, 2009) – and – When jobs are being lost think macro first (January 21, 2013) – I discussed the concept of a Just Transition framework to ensure that the costs of economic restructuring do not fall on workers in targeted industries and their communities.

These sort of adjustments, require government support and intervention to ensure that displaced workers are able to transit into the new industries and jobs quickly.

National governments should introduce integrated employment guarantee/skills development frameworks to maintain income security and capacity building while regions adjust from old technology to new, smart processes.

On the question of incentives, I generally do not favour handing out public incentives to private firms. I see this as a denial of ‘capitalism’. If private firms want the returns then they should take the risk.

However, I do support public enterprise and partnerships with local not-for-profit co-operatives. There is so much need in the area of personal care and environmental care services now as populations age and the environmental damage of our past thoughtless industry and farming practices mount, that there is more than enough public sector work to be done to absorb displaced workers should that be required.

Second, many new jobs in these ‘smart’ manufacturing processes will be taken by robots, which will also increasingly provide services as they become more intelligent and dexterous.

The introduction of the – Job Guarantee – has to be seen as part of this increased public employment capacity, given that many of those displaced by industrial shifts will be those with low skills and little capacity to retrain to work in the high-tech sectors.

The public sector will have to play an increased role also in providing high skilled work for those who are displaced by robotic innovations.

As noted above, there will be growing demand for workers of all skills in the areas of personal care (as populations age) and community development, so there is little reason to fear the spread of robots.

The challenge of government is to ensure the distribution system maintains the capacity of workers who do not work in these high productivity sectors (where productivity is narrowly defined here) to enjoy real wages growth.

Third, this also suggests that a progressive agenda must be one that works to broaden the definition of productive work so that new areas of employment can be created within the public sector to provide on-going opportunities for local workers who lose out when trade undermines their jobs.

Please read my blog – Employment guarantees are better than income guarantees – for more discussion on this point.

The old definition of gainful labour was biased towards activity that supported private profit generation within labour intensive, large-scale assembly production models.

Through appropriate regionally-focused policy interventions, workers who find their employment is displaced by trade effects, can still contribute to society through meaningful work that both provides them with income security but also ensures that income and wealth inequalities are reduced.

If productivity is enhanced by the smart part of the local labour market, then everyone benefits! That should be the aim of public investment in these smart innovation hubs.

Dani Rodrik says that the:

… the gains from trade can be redistributed to compensate the losers and ensure no identifiable group is left behind.

He recommends “strong social protections and a generous welfare state” but recognises that one-off compensation policies are too easily reneged on by government.

That is why a coherent and permanent ‘Just Transition framework’ is required. A Job Guarantee, for example, is not an ephemeral response to trade-displacements in labour markets.

It is part of the permanent base line stability tools that currency-issuing governments should always employ.

Finally, there might be certain sectors (products) that need protection – say for national security purposes. Whether that is correct depends on a case by case analysis.

But that doesn’t require blanket protection.

Conclusion

Donald Trump’s tariff hikes are not good policy and will likely be counterproductive.

The US government has all the fiscal capacity it needs to ensure that the trade-displacing impacts on specific cohorts of workers and regions can be attenuated.

Using that capacity to create jobs in the regions impacted by import competition is a far better strategy than punishing all consumers with higher prices whether they be for final goods and services or intermediary inputs.

That is a dumb approach.

Dealing with the ridiculous trade surplus obsessions adopted by European nations is another matter altogether. In that context, Trump has the power and could force shifts in European thinking.

Don’t hold your breathe on that though.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2018 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Dear Bill

From 1815 to 1914, the US was protectionist, but it also became the richest country in the world. If the protected market is large enough, there will be lots of firms who compete against other and have an incentive to innovate. Protectionism should not be applied by small countries on their own. They should join a protectionist group. For instance, Uruguay and Paraguay have joined Brazil and Argentina to form Mercosur, a customs union that has 260 million inhabitants. Mexico, Venezuela, Columbia and the Central American countries could form a trading bloc. Trading blocs should take place between countries that have roughly the same level of development.

Protectionist measures are party offset by an increase in the exchange rate. Conversely, trade liberalization will be partly nullified by a decrease in the exchange rate. Suppose that Mexico is protectionist. It imports and exports 100 billion, and the peso is worth 0.2 USD. Now Mexico liberalizes its trade. The result will be more imports and an excess demand for USD, which will lead to an devaluation of the peso, which may end up being worth 0.16 USD. This cheaper peso will discourage imports, thereby offsetting the effect of trade liberalization. The new equilibrium may be 120 billion of imports and exports.

On the other hand, if Mexico goes from free trade to protectionism, the value of its peso will rise to, say, 0.25 USD because there will be an excess supply of USD. A more expensive peso will make imports more attractive, thereby reducing the effect of the protectionist measures. I’m assuming that there are no capital flows between Mexico and the rest of the world.

Regards. James

If the deal announced yesterday is anything to go by, it seems that the UK’s Brexit negotiators (for all their bluster) are not smart enough to exploit their strong position. They couldn’t even sort out Fishing properly, which even the Scottish Tory leader (Ruth Davidson – a far more charismatic figure than Theresa May, and probably smarter) said should have been easy, and a high priority.

Brexit by all means, but not with these clowns in the driving seat.

Mike is right. Davis and his team seem to be clueless and quite poor negotiators, if you can call what they have been doing negotiation. I would normally recommend you send your post to Davis and others but I hate these bastards so much that I want them to fail and produce the disaster that they seem to be unable to prevent themselves creating.

Mike’s position is the same as that of Richard North — Brexit would in principle be good but not with these cretins. John Crace has a quite amusing take on the recent press conference by Davis and Barnier in today’s Guardian — where green is the new red.

Protectionism, mercantilism and employmentism are alike all palliatives…and old paradigm.

The account of Austrailia’s experiencee with protectionism was very interesting.

Reading Joe Studwell you can read how protectionism failed in malayasia as they misapplies parts of Japanese industrial strategy.

The Japanese and South Korean and Taiwanese would link subsidy support to export volumes achieved by firms. which would allow firms to compete against the global best but also benefit from state support.Unless they fail in export markets,in which case support would be rescinded.This has to be a applied to a multitude of

Competing firms;not just one national champion.

Is that why austrailian car manufacturing never left it infancy,unconditionial support to one firm?

Don’t give up on Aussie manufacturing just Yet.

I think its worthwhile for an country to develop all productive capacity.

Even if it would just be a future of automated robots and 3d printers.

Brilliant.

Interesting the detail of the European pain if…

“Finally, there might be certain sectors (products) that need protection – say for national security purposes. Whether that is correct depends on a case by case analysis.”

The main concern with the ‘import’ policy is diversity of supply. Since you don’t and can’t control the output of foreign territories, you have to cover your country by diversifying supply, and that supply has to have sufficient expansion capacity to handle one or more of the other suppliers trying to impose ‘sanctions’ – for whatever political purpose that may entail.

This suggests you should maintain in internal capacity in any production considered vital to keeping a nation of people together – particularly food and energy supply, as well as defence.

What I’ve noticed about mainstream economics is that they appear to value efficiency over all other considerations – driving a nation down to monoculture in vast cities in pursuit of that goal. However that level of centralisation makes the system very brittle indeed. Network effects show there is always a trade off between efficiency and resilience. No natural system goes all out for efficiency. It would become extinct very quickly.

Dr. Mitchell, I see that you had a negative experience in Australia of tariffs and the quality of the product produced. But hadn’t some other countries uses tariffs to develop productive industries? The South Koreans have world-class steel-making, shipbuilding, automotive, white goods, and electronics industries. Many of these industries would not exist were it not for the protection provided by the government. For instance, Korea has no substantial sources of coal or iron ore that make steel-making an obvious industry, but today the industry employs thousands of workers and contributes to GDP.

Perhaps the amount of corruption necessary to achieve these goals more than offsets the gains in the industries, but from outside appearances they seem to perform quite well, and produce high-quality products.

Joel

Great content.

I read Mr.Chang book after picking it up at a college bookstore. Great of you to point out the problem with the infant industry approach and gave a good example. I never considered that.

However, I am not very comfortable about leaving sectors completely dominated by foreign companies/factories. It just seem that one is relying on others too much. Isn’t self-sufficiency an important consideration too?

“The secret is for governments to realise they have the fiscal capacity to introduce appropriate transitional adjustments.”

“These sort of adjustments, require government support and intervention to ensure that displaced workers are able to transit into the new industries and jobs quickly.”

Is this a “secret” worth knowing?

Aren’t these statements just too glib?

Ask a displaced auto worker how he feels about being retrained to empty bed pans for the elderly.

Anyway, if robotics and AI make substantial inroads into the workplace, then the way society works will have to radically change.

So maybe the majority will have to be content with working at menial tasks.

If you effectively have your car, your house, your recreational facilities, etc., given to you, then performing menial tasks for a few hours a week may not be so unpalatable.

I wonder how many sports fishing boats and golf clubs an economy can produce or how tolerant society might be of drug addled dropouts littering our streets?

Henry Rech,

You can imagine all kinds of scenarios where any policy won’t work.

If a displaced auto worker wants to take care of old people, why not train/pay him/her to do that?

You are probably right about AI that society must change. I haven’t worried about it though.

“if you have your car given to you…”

If we are getting what we want for free, we won’t be in so much private debt.

Good point. If anything, natural systems optimise for redundancy, e.g. the human body. And even parts for which we apparently no longer have any use (the appendix), haven’t yet been evolved out of existence.

@ Henry Rech,

It’s simple. First employment has a long way to go yet, and if profit making systems are no longer demand constrained we’ll certainly have more of it than if we idiotically impose austerity on the economy and ourselves. Secondly, what you do is what the mentally healthy rich have done since forever, namely find additional positive and constructive purposes IN ADDITION TO employment. You accomplish this by implementing a cooperative effort between the clergy, the helping professions and the government in awakening people to the incredibly large set of such purposes and in so doing acculturate leisure (and hopefully at least a modicum of contemplation) neither of which is idleness, but rather self chosen directed attention.

Trade has done some some some strange things to the global income distribution. Workers in low wage economies have seen their wages rise. It’s mostly the effect of China’s industrial revolution. Over the last 30 years, they have been enjoying the benefits of modern economic growth and I wouldn’t begrudge them that. It’s only the incomes of wage earners in the developed world that have stagnated.

Noeliberalism has gamed trade to suppress wages and export jobs to the developing world in labour intensive industries. China has helped by manipulating exchange rates. Doesn’t a country as poor as China remains per capita have better things to do with US dollars they were earning from their exports than buy Treasury Bills to inflate the value of the USD artificially?

Germany of course has essentially an exports good, imports bad outlook and the Eurozone imposes austerity on any member that has a propensity to run current account deficits. How that’s supposed to deliver a sustainable outcome when Germany runs a surplus against the rest of the Eurozone is beyond me. The Germans can’t have their cake and eat it on that one. If they want to export, they need partners who can afford to buy what they’re exporting. It might be bad policy; but if Trump denies them access to American markets, the Germans might just realise they need the Greeks after all and cut them some slack.

Overall Trump is relying on trickle down when it comes to his tax cuts. It won’t work will it? In addition, he knows the neoliberal intelligentsia will demand spending cuts to balance the books. This will only skew the income distribution in the richest’s favour even more. He knows he has to deliver on his promise to protect American jobs and working families’ incomes or his electoral base will evaporate. He is posturing to create an impression he is going that by imposing tariffs.

Of course the fact that Germans build better cars than Americans and Mexicans can build basic cars more cheaply than Americans wouldn’t matter if the USA was at full employment. The Americans worker would have more important things to do and get on with it.

This is the real problem with trade in the neoliberal age. It’s used to produce a global convergence in wages that might benefit the lowest paid, but puts pressure on the middle. It only works if a commitment to full employment to ensures its winners get their due rewards without hurting its losers.

Jake

Autralia gave unconditional support to several car manufacturers. GM was here in the shape of Holden. Ford too! We had various bits of the Austin, Morris, etc. that morphed into BMC and then British Leyland. The Brits pulled out in the 70s. We also had Chrysler before they sold to Mitsubishi and Toyota also had a presence.

Problem is car manufacture realises economies of scale. If your not using Australia as an export hub, you’re just not going to realise them in the domestic market. It wasn’t all doom and gloom. There were some very talented people in the industry but the levels of protection needed to give them breathing space were horrendously expensive.

Interesting. Is that what happens? (Genuine question: I should know perhaps, but I don’t). I know they buy Treasuries, but I didn’t know about the effect on the exchange rate. I suppose it must be the same as buying USD in the foreign exchange market (except that they are buying Treasuries with the USD they earned from the exports).

I was amused / bemused when Trump was railing against the Chinese in his election campaign, thinking back to (e.g.) what Warren Mosler has talked about several times (and no doubt other MMTers have as well), about China sending real cars to Americans, and getting in exchange electronic dollars which it then proceeds to exchange for electronic Treasuries, and what is the problem [for Americans] with this?

Well, it means that not so many Americans are employed making cars of course, but Americans can do many other things.

My understanding is that this is pretty much how currency manipulation is done when you have a trade surplus. You keep the USD you’re earning from net exports off the foreign exchanges by either stuffing them under a bed or parking them in safe haven like US Treasury Bills. Surely the Chinese would be better off importing something from the US instead.

And yes Americans do have other things to do rather than making cars, but if all that’s on offer in Michigan is yet another low paid job at Walmart you should not be surprised if there’s a backlash.

OK, I see. thank you.

True. If Trump were a statesman like J F Kennedy, and not a scumbag like he is, he’d put his mind…well, put a team, to work on creating new, worthwhile jobs (i.e. a Job Guarantee scheme), instead of making unnecessary enemies with China.

“I was amused / bemused when Trump was railing against the Chinese in his election campaign, thinking back to (e.g.) what Warren Mosler has talked about several times (and no doubt other MMTers have as well), about China sending real cars to Americans, and getting in exchange electronic dollars which it then proceeds to exchange for electronic Treasuries, and what is the problem [for Americans] with this?

Well, it means that not so many Americans are employed making cars of course, but Americans can do many other things.”

I tend to feel that the view taken by many MMT proponents that sacrificing a nations productive industries and importing more cheaply instead is largely irrelivent because the exporting nation is giving up real, physical resources in exchange for abstact media that a fully sovereign nation can issue in unlimited quantities as being one of the more naive beliefs held by otherwise highly intelligent people.

The nation who ends up with the industry has gained so much more than just electronic entries on a spreadsheet – they have gained ownership of the means of production and all side benefits arising from that. The monumental stupidity of Abbot and Hockey in deliberately slashing the throat of the Australian car making industry has cost us the ability to engage advanced mechanical engineering – anyone who views this as being inconsequential has their head in the clouds (or somewhere else).

We are on a remarkable crusade to dumb ourselves down as much as possible, to the point where we can do little more than make each other coffee and sell each other real estate and are totally reliant on people on the other side of the world to supply us with all of our needs – what could possibly go wrong?

There’s not much point arguing that protection kept certain local industries in a state of infancy when completely removing it is causing the nation as a whole to regress toward a state of such utter dependence.

@Leftwinghillbillyprospector

I hear what you are saying, loud and clear, and I regret the hollowing out of manufacturing industry in my own country (the UK), as much as you do in yours.

(Of course, the people responsible for that were not propoents of MMT…).

But it was partly because we had become utterly complacent, lazy and unimaginative. Frankly, we deserved to lose it. Bad management was part of it, plus lack of investment & imagination on the part of both government and private industry, plus short-termism.

And it wasn’t just in metal-bashing. We almost had a world-beating high-tech industry in computing, but we made a mess of that as well. Very sad.

“Surely the Chinese would be better off importing something from the US instead.”

FWIW the web page at https://ustr.gov/countries-regions/china-mongolia-taiwan/peoples-republic-china summarizes US exports to China. Total in 2016 was $115.6 billion. Of that, U.S. exports of agricultural products to China totaled $21 billion. China exported $4.3 billion in agricultural products to U.S. Which one looks like the low-tech economy?

Higher tech stuff: aircraft ($15 billion), electrical machinery ($12 billion), machinery ($11 billion) and vehicles ($11 billion).

$54.2 billion in services, including travel, intellectual property (trademark, computer software) and transport. Not big job generators there.

Very possibly, China is already importing what there is to import, and they’re just stuck with finding something, anything, to do with the extra money.

Hi Mel

what do they do with the excess money?

It may interest you to know that the largest buyer of Commercial Office Buildings in the Brisbane Australia Market (a city with about 1.6mil people) last year was German Funds. (CBRE Research)

Local investors and funds cant outbid the Germans who seem to have free money! The money system is broken. Funds are roaming the world buying anything that can be valued to satisfy Asset Committees.

The system is way out of any sort of balance. Trade wars are just part of the mess.

baby boomers in the OECD countries the only generation that

will ever own their own house as the norm?

I am equally concerned about the accumulation of claims on the

worlds resources and others labour .I am concerned even at the national level let alone

at the international level.

Bill I feel you have unfairly denigrated the Australian automotive industry. Most of those derogatory stories were exaggerations and applied to many decades ago. As a former production engineer for Toyota’s manufacturing operations in Melbourne I can offer some insights. The Toyota Altona plant had equivalent quality and costs of production to the almost identical Toyota plants in the UK, the US and Japan. Exports, mainly to the Middle East, ensured the plant operated near to capacity. The plant was continuously modernised, for example the engine plant was only two years old when the closure announcement was made in late 2013 and the Altona plant was state of the art for current generation vehicles. The Toyota plant in Thailand however had a cost of production of about 10% less than the Altona plant due to lower labour costs and lower government imposed costs.

Toyota Australian manufacturing operations received a subsidy of about $85 million per annum for sales of about 100,000 units per annum. The industry would have however preferred the certainty and simplicity of a moderate import tariff of 15% to ensure local manufacturing was more profitable than importing but both parts of the duopoly were and remain adherents to the philosophy of totally open markets for manufactured goods.

The Toyota Altona plant cost about $1 billion to build but would probably cost about twice that to build now. It is now being dismantled and the machinery is being relocated to other Toyota plants, sold at auction or scrapped.

Australia buys over one million passenger vehicles per year and this is valued at about $30 billion per year. With a 15% tariff and the appropriate industrial policy settings Australia could just have easily set about manufacturing half of the Australian vehicle demand locally plus exports with equal quality and cost of production as the main manufacturing nations but not quite as cheaply as Thailand or China. Now this option has probably been forever denied.

The automotive market in my opinion was too big too abandon and this industry ensured the viability of a substantial supply chain. Similarly the white goods industry should also have been retained. Over time most of Australia’s heavy industry, building materials industry and much of the food processing industry will now also be lost.

Australia was never the world’s lowest cost producer of any manufactured goods but we got fairly close and I firmly believe that moderate trade protection that allows import penetration up to 50% of local market demand provides the optimal overall benefit in terms of national economic capacity, employment and with meeting consumer choice and needs.

Steve Keen has written about how a loss of economic complexity and diversity harms a nation and the ability to establish viable businesses that are closely related to existing businesses.

Now we have an economy that is overly dependent on raw material exports most of which have poor prospects in a carbon constrained world, an overly financialised economy that exploits consumers, record levels of property speculation and unsustainable private debt, excessive gambling and private sector taxes in the form of privatised utilities, public transport, toll roads, private schools, privatised health services and other infrastructure.

You economists have well and truly stuffed this countries future prospects.

I also don’t want to empty bed pans or weed the local park in some Job Guarantee program and have had enough of irregular work as a domestic painting contractor for less than the minimum wage and no benefits and an ongoing inability to pay for basic necessities.

I think that the work of all economists and academics in Australia could be performed more productively by developing world competitors but unlike you lot I wouldn’t support such a change.

USD are the predominant global trading currency, US have since the 80s acted as consumer of last resort, keeping global trade afloat. On could just imagine what a disaster it would have been if EU/Germany was to have that role. Without US deficits no export-tigers.

This are the common mainstream economist thing, export led growth. The world spin on fiat-money, but to make them your self is no-no in this ideology, someone else should make them (out of thin air).

So what EU are saying to Trump is, we demand US deficits to survive. As we did see in GFC a halt in US did stop the entire world trade, huge merchant navy fleets laying idle outside Singapore, China and all around the world.

One can time to time hear politicians in Sweden boost them self about our trade surplus and then almost in the next sentence be concerned over US huge deficits, they should do as we do are their recipe.

Trump make sense in mainstream economic thinking everyone should do something about trade deficits. But now if US should come to surplus, what should they accumulate? Chinese Yuan, Euro, Turkish lira, Indian rupee? All of them fiat currencies. Or should he demand the surplus paid in gold?

From an imperial/global hegemony perspective it was probably not so clever idea of corporate America to super wash the Chinese with a mountain of US deficit dollars, that still are good as “gold” on the global market. Why did they do that, to squeeze the US worker?

2017 Top 5 contributors to the export led growth cabal:

United States -$462,000,000,000 2017 est

United Kingdom -$91,420,000,000 2017 est.

Canada -$55,570,000,000 2017 est.

Turkey -$38,950,000,000 2017 est.

India -$33,680,000,000 2017 est.

Top 5 beneficiaries:

European Union $387,100,000,000 201

Germany $296,000,000,000 2017 est.

Japan $175,000,000,000 2017 est.

China $162,500,000,000 2017 est.

Korea, South $85,140,000,000 2017 es

Netherlands $82,440,000,000 2017 est.

CIA Factbook, current account top list.

@/lasse,

Interesting, thanks. Fascinating how much the little Netherlands “punches above its weight” if you want to think in those terms.

Jan Kregel on trade (12 min):

https://ytcropper.com/cropped/X35ab8e6451c709

a crop from:

Modern Money & Public Purpose 4: Real vs. Nominal Economy (+ 2 hours)

https://youtu.be/X39M9MXRNyg

@/lasse,

Thank you for that. What did he mean when he said China couldn’t run a deficit? (I think he meant fiscal deficit?).

@ Mike E

Not sure, but maybe he meant they don’t want to run a deficit. But it’s different to operate on a global scale in your own fiat-money like US. If China tried to go on a global shopping spree with freshly “printed” Renminbi/Yuan it would not be accepted, the RMB would collapse. It’s the privilege of the empire. And to a minor degree some other currencies with semi-reserve status. All the rest must do it with someone else global “hard” currencies, to run CC deficits.

As I understand it he uses a lot of sarcasm in this “lecture”, like when he say that it’s much better to lend money to foreigners than to lend to yourself. He explains from how the present economic paradigm are looking at problem and solutions.

For China this make sense, they build up industrial knowledge and can shop with globally accepted USD. I think the parallel with post war US are wrong, US wasn’t a developing nation then. Economics cant be isolated from politics and power struggle.

But why are an industrialized mature region as most of EU/EZ act like China? In EU the result is the rich get richer and the poor poorer.

He also had an interesting explanation of Mexico’s tequila crisis, especially from an MMT perspective.

Starts about here on economics for developing nations: https://youtu.be/X39M9MXRNyg?t=1h42m01s

All of Mexico’s public debt was denominated in Peso. But was traded internationally and big global banks and financial institutions did hold a significant part. So, when they unanimously decided to get rid of Mexican Peso bonds the Peso skydived to zero. Almost instantly there where tenth of billions of (in USD) peso for sale.