Here are the answers with discussion for this Weekend’s Quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of Modern…

The Weekend Quiz – June 24-25, 2017 – answers and discussion

Here are the answers with discussion for this Weekend’s Quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of modern monetary theory (MMT) and its application to macroeconomic thinking. Comments as usual welcome, especially if I have made an error.

Question 1:

Issuing government debt reduces the risk of inflation arising from deficit spending because the private sector has less money to spend.

The answer is False.

The mainstream macroeconomic textbooks all have a chapter on fiscal policy (and it is often written in the context of the so-called IS-LM model but not always).

The chapters always introduces the so-called Government Budget Constraint that alleges that governments have to “finance” all spending either through taxation; debt-issuance; or money creation. The writer fails to understand that government spending is performed in the same way irrespective of the accompanying monetary operations.

They claim that money creation (borrowing from central bank) is inflationary while the latter (private bond sales) is less so. These conclusions are based on their erroneous claim that “money creation” adds more to aggregate demand than bond sales, because the latter forces up interest rates which crowd out some private spending.

All these claims are without foundation in a fiat monetary system and an understanding of the banking operations that occur when governments spend and issue debt helps to show why.

So what would happen if a sovereign, currency-issuing government (with a flexible exchange rate) ran a budget deficit without issuing debt?

Like all government spending, the Treasury would credit the reserve accounts held by the commercial bank at the central bank. The commercial bank in question would be where the target of the spending had an account. So the commercial bank’s assets rise and its liabilities also increase because a deposit would be made.

The transactions are clear: The commercial bank’s assets rise and its liabilities also increase because a new deposit has been made. Further, the target of the fiscal initiative enjoys increased assets (bank deposit) and net worth (a liability/equity entry on their balance sheet). Taxation does the opposite and so a deficit (spending greater than taxation) means that reserves increase and private net worth increases.

This means that there are likely to be excess reserves in the “cash system” which then raises issues for the central bank about its liquidity management. The aim of the central bank is to “hit” a target interest rate and so it has to ensure that competitive forces in the interbank market do not compromise that target.

When there are excess reserves there is downward pressure on the overnight interest rate (as banks scurry to seek interest-earning opportunities), the central bank then has to sell government bonds to the banks to soak the excess up and maintain liquidity at a level consistent with the target. Some central banks offer a return on overnight reserves which reduces the need to sell debt as a liquidity management operation.

There is no sense that these debt sales have anything to do with “financing” government net spending. The sales are a monetary operation aimed at interest-rate maintenance. So M1 (deposits in the non-government sector) rise as a result of the deficit without a corresponding increase in liabilities. It is this result that leads to the conclusion that that deficits increase net financial assets in the non-government sector.

What would happen if there were bond sales? All that happens is that the banks reserves are reduced by the bond sales but this does not reduce the deposits created by the net spending. So net worth is not altered. What is changed is the composition of the asset portfolio held in the non-government sector.

The only difference between the Treasury “borrowing from the central bank” and issuing debt to the private sector is that the central bank has to use different operations to pursue its policy interest rate target. If it debt is not issued to match the deficit then it has to either pay interest on excess reserves (which most central banks are doing now anyway) or let the target rate fall to zero (the Japan solution).

There is no difference to the impact of the deficits on net worth in the non-government sector.

Mainstream economists would say that by draining the reserves, the central bank has reduced the ability of banks to lend which then, via the money multiplier, expands the money supply.

However, the reality is that:

- Building bank reserves does not increase the ability of the banks to lend.

- The money multiplier process so loved by the mainstream does not describe the way in which banks make loans.

- Inflation is caused by aggregate demand growing faster than real output capacity. The reserve position of the banks is not functionally related with that process.

So the banks are able to create as much credit as they can find credit-worthy customers to hold irrespective of the operations that accompany government net spending.

This doesn’t lead to the conclusion that deficits do not carry an inflation risk. All components of aggregate demand carry an inflation risk if they become excessive, which can only be defined in terms of the relation between spending and productive capacity.

It is totally fallacious to think that private placement of debt reduces the inflation risk. It does not.

You may wish to read the following blogs for more information:

- Why history matters

- Building bank reserves will not expand credit

- Building bank reserves is not inflationary

- The complacent students sit and listen to some of that

- Saturday Quiz – February 27, 2010 – answers and discussion

Question 2:

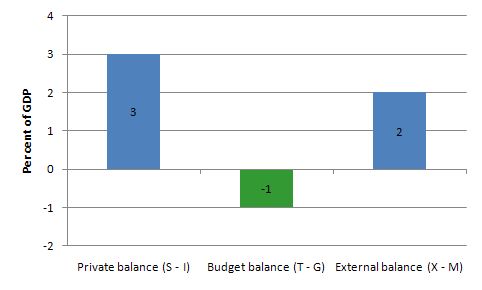

If net exports are running at 2 per cent of GDP, and the private domestic sector overall is saving an equivalent of 3 per cent of GDP, the government must be running a surplus equal to 1 per cent of GDP.

The answer is False.

The correct answer is that the government must be running a deficit equal to 1 per cent of GDP.

This question tests your knowledge of the sectoral balances that are derived from the National Accounts.

To refresh your memory the balances are derived as follows. The basic income-expenditure model in macroeconomics can be viewed in (at least) two ways: (a) from the perspective of the sources of spending; and (b) from the perspective of the uses of the income produced. Bringing these two perspectives (of the same thing) together generates the sectoral balances.

From the sources perspective we write:

(1) GDP = C + I + G + (X – M)

which says that total national income (GDP) is the sum of total final consumption spending (C), total private investment (I), total government spending (G) and net exports (X – M).

Expression (1) tells us that total income in the economy per period will be exactly equal to total spending from all sources of expenditure.

We also have to acknowledge that financial balances of the sectors are impacted by net government taxes (T) which includes all tax revenue minus total transfer and interest payments (the latter are not counted independently in the expenditure Expression (1)).

Further, as noted above the trade account is only one aspect of the financial flows between the domestic economy and the external sector. we have to include net external income flows (FNI).

Adding in the net external income flows (FNI) to Expression (2) for GDP we get the familiar gross national product or gross national income measure (GNP):

(2) GNP = C + I + G + (X – M) + FNI

To render this approach into the sectoral balances form, we subtract total net taxes (T) from both sides of Expression (3) to get:

(3) GNP – T = C + I + G + (X – M) + FNI – T

Now we can collect the terms by arranging them according to the three sectoral balances:

(4) (GNP – C – T) – I = (G – T) + (X – M + FNI)

The the terms in Expression (4) are relatively easy to understand now.

The term (GNP – C – T) represents total income less the amount consumed less the amount paid to government in taxes (taking into account transfers coming the other way). In other words, it represents private domestic saving.

The left-hand side of Equation (4), (GNP – C – T) – I, thus is the overall saving of the private domestic sector, which is distinct from total household saving denoted by the term (GNP – C – T).

In other words, the left-hand side of Equation (4) is the private domestic financial balance and if it is positive then the sector is spending less than its total income and if it is negative the sector is spending more than it total income.

The term (G – T) is the government financial balance and is in deficit if government spending (G) is greater than government tax revenue minus transfers (T), and in surplus if the balance is negative.

Finally, the other right-hand side term (X – M + FNI) is the external financial balance, commonly known as the current account balance (CAD). It is in surplus if positive and deficit if negative.

In English we could say that:

The private financial balance equals the sum of the government financial balance plus the current account balance.

We can re-write Expression (6) in this way to get the sectoral balances equation:

(5) (S – I) = (G – T) + CAD

which is interpreted as meaning that government sector deficits (G – T > 0) and current account surpluses (CAD > 0) generate national income and net financial assets for the private domestic sector.

Conversely, government surpluses (G – T < 0) and current account deficits (CAD < 0) reduce national income and undermine the capacity of the private domestic sector to add financial assets.

Expression (5) can also be written as:

(6) [(S – I) – CAD] = (G – T)

where the term on the left-hand side [(S – I) – CAD] is the non-government sector financial balance and is of equal and opposite sign to the government financial balance.

This is the familiar MMT statement that a government sector deficit (surplus) is equal dollar-for-dollar to the non-government sector surplus (deficit).

The sectoral balances equation says that total private savings (S) minus private investment (I) has to equal the public deficit (spending, G minus taxes, T) plus net exports (exports (X) minus imports (M)) plus net income transfers.

All these relationships (equations) hold as a matter of accounting and not matters of opinion.

Thus, when an external deficit (X – M < 0) and public surplus (G – T < 0) coincide, there must be a private deficit. While private spending can persist for a time under these conditions using the net savings of the external sector, the private sector becomes increasingly indebted in the process.

Second, you then have to appreciate the relative sizes of these balances to answer the question correctly.

The rule is that the sectoral balances have to sum to zero. So if we write the condition above as:

(S – 1) – (G – T) – (X – M) = 0

And substitute the values of the question we get:

3 – (G – T) – 2 = 0

We can solve this for (G – T) as

(G – T) = 3 – 2 = 1

Given the construction (G – T) a positive number (1) is a deficit.

The outcome is depicted in the following graph.

This tells us that even if the external sector is growing strongly and is in surplus there may still be a need for public deficits. This will occur if the private domestic sector seek to save at a proportion of GDP higher than the external surplus.

The economics of this situation might be something like this. The external surplus would be adding to overall aggregate demand (the injection from exports exceeds the drain from imports). However, if the drain from private sector spending (S > I) is greater than the external injection then the only way output and income can remain constant is if the government is in deficit.

National income adjustments would occur if the private domestic sector tried to push for higher saving overall – income would fall (because overall spending fell) and the government would be pushed into deficit whether it liked it or not via falling revenue and rising welfare payments.

You may wish to read the following blogs for more information:

- Back to basics – aggregate demand drives output

- Stock-flow consistent macro models

- Norway and sectoral balances

- The OECD is at it again!

- Barnaby, better to walk before we run

- Saturday Quiz – June 19, 2010 – answers and discussion

Question 3

To reduce the public debt ratio, the government has to eventually run primary fiscal surpluses.

The answer is False.

This question requires you to understand the key parameters and relationships that determine the dynamics of the public debt ratio. An understanding of these relationships allows you to debunk statements that are made by those who think fiscal austerity will allow a government to reduce its public debt ratio.

It also requires you to differentiate between the level of outstanding public debt and the ratio of public debt to GDP. The question is focusing on the latter concept.

While Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) places no particular importance in the public debt to GDP ratio for a sovereign government, given that insolvency is not an issue, the mainstream debate is dominated by the concept.

The unnecessary practice of fiat currency-issuing governments of issuing public debt $-for-$ to match public net spending (deficits) ensures that the debt levels will rise when there are deficits.

Rising deficits usually mean declining economic activity (especially if there is no evidence of accelerating inflation) which suggests that the debt/GDP ratio may be rising because the denominator is also likely to be falling or rising below trend.

Further, historical experience tells us that when economic growth resumes after a major recession, during which the public debt ratio can rise sharply, the latter always declines again.

It is this endogenous nature of the ratio that suggests it is far more important to focus on the underlying economic problems which the public debt ratio just mirrors.

Mainstream economics starts with the flawed analogy between the household and the sovereign government such that any excess in government spending over taxation receipts has to be “financed” in two ways: (a) by borrowing from the public; and/or (b) by “printing money”.

Neither characterisation is remotely representative of what happens in the real world in terms of the operations that define transactions between the government and non-government sector.

Further, the basic analogy is flawed at its most elemental level. The household must work out the financing before it can spend. The household cannot spend first. The government can spend first and ultimately does not have to worry about financing such expenditure.

However, the mainstream framework for analysing these so-called “financing” choices is called the government budget constraint (GBC). The GBC says that the fiscal deficit in year t is equal to the change in government debt over year t plus the change in high powered money over year t. So in mathematical terms it is written as:

which you can read in English as saying that Budget deficit = Government spending + Government interest payments – Tax receipts must equal (be “financed” by) a change in Bonds (B) and/or a change in high powered money (H). The triangle sign (delta) is just shorthand for the change in a variable.

However, this is merely an accounting statement. In a stock-flow consistent macroeconomics, this statement will always hold. That is, it has to be true if all the transactions between the government and non-government sector have been corrected added and subtracted.

So in terms of MMT, the previous equation is just an ex post accounting identity that has to be true by definition and has not real economic importance.

But for the mainstream economist, the equation represents an ex ante (before the fact) financial constraint that the government is bound by. The difference between these two conceptions is very significant and the second (mainstream) interpretation cannot be correct if governments issue fiat currency (unless they place voluntary constraints on themselves to act as if it is).

Further, in mainstream economics, money creation is erroneously depicted as the government asking the central bank to buy treasury bonds which the central bank in return then prints money. The government then spends this money.

This is called debt monetisation and you can find out why this is typically not a viable option for a central bank by reading the Deficits 101 suite – Deficit spending 101 – Part 1 – Deficit spending 101 – Part 2 – Deficit spending 101 – Part 3.

Anyway, the mainstream claims that if governments increase the money growth rate (they erroneously call this “printing money”) the extra spending will cause accelerating inflation because there will be “too much money chasing too few goods”! Of-course, we know that proposition to be generally preposterous because economies that are constrained by deficient demand (defined as demand below the full employment level) respond to nominal demand increases by expanding real output rather than prices. There is an extensive literature pointing to this result.

So when governments are expanding deficits to offset a collapse in private spending, there is plenty of spare capacity available to ensure output rather than inflation increases.

But not to be daunted by the “facts”, the mainstream claim that because inflation is inevitable if “printing money” occurs, it is unwise to use this option to “finance” net public spending.

Hence they say as a better (but still poor) solution, governments should use debt issuance to “finance” their deficits. Thy also claim this is a poor option because in the short-term it is alleged to increase interest rates and in the longer-term is results in higher future tax rates because the debt has to be “paid back”.

Neither proposition bears scrutiny – you can read these blogs – Will we really pay higher taxes? and Will we really pay higher interest rates? – for further discussion on these points.

The mainstream textbooks are full of elaborate models of debt pay-back, debt stabilisation etc which all claim (falsely) to “prove” that the legacy of past deficits is higher debt and to stabilise the debt, the government must eliminate the deficit which means it must then run a primary surplus equal to interest payments on the existing debt.

A primary fiscal balance is the difference between government spending (excluding interest rate servicing) and taxation revenue.

The standard mainstream framework, which even the so-called progressives (deficit-doves) use, focuses on the ratio of debt to GDP rather than the level of debt per se. The following equation captures the approach:

So the change in the debt ratio is the sum of two terms on the right-hand side: (a) the difference between the real interest rate (r) and the real GDP growth rate (g) times the initial debt ratio; and (b) the ratio of the primary deficit (G-T) to GDP.

The real interest rate is the difference between the nominal interest rate and the inflation rate. Real GDP is the nominal GDP deflated by the inflation rate. So the real GDP growth rate is equal to the Nominal GDP growth minus the inflation rate.

An appreciation of the elements of the public debt ratio immediately tells us that a currency-issuing government running a deficit can reduce the debt ratio. There is no need to run primary surpluses and unnecessarily reduce growth. The standard formula above can easily demonstrate that a nation running a primary deficit can reduce its public debt ratio over time.

Furthermore, depending on contributions from the external sector, a nation running a deficit will more likely create the conditions for a reduction in the public debt ratio than a nation that introduces an austerity plan aimed at running primary surpluses.

Here is why that is the case.

A growing economy can absorb more debt and keep the debt ratio constant or falling. From the formula above, if the primary fiscal balance is zero, public debt increases at a rate r but the public debt ratio increases at r – g.

The following Table simulates the two years in question. To make matters simple, assume a public debt ratio at the start of the Year 1 of 100 per cent (so B/Y(-1) = 1) which is equivalent to the statement that “outstanding public debt is equal to the value of the nominal GDP”.

Also the nominal interest rate is 1 per cent and the inflation rate is 1 per cent then the current real interest rate (r) is 0 per cent.

If the nominal GDP is growing at -1 per cent and there is an inflation rate of 1 per cent then real GDP is growing (g) at minus 2 per cent.

Under these conditions, the primary fiscal surplus would have to be equal to 2 per cent of GDP to stabilise the debt ratio (check it for yourself). So, the question suggests the primary fiscal deficit is actually 1 per cent of GDP we know by computation that the public debt ratio rises by 3 per cent.

The calculation (using the formula in the Table) is:

Change in B/Y = (0 – (-2))*1 + 1 = 3 per cent.

The data in Year 2 is given in the last column in the Table below. Note the public debt ratio has risen to 1.03 because of the rise from last year. You are told that the fiscal deficit doubles as per cent of GDP (to 2 per cent) and nominal GDP growth shoots up to 4 per cent which means real GDP growth (given the inflation rate) is equal to 3 per cent.

The corresponding calculation for the change in the public debt ratio is:

Change in B/Y = (0 – 3)*1.03 + 2 = -1.1 per cent.

So the growth in the economy is strong enough to reduce the public debt ratio even though the primary fiscal deficit has doubled.

It is a highly stylised example truncated into a two-period adjustment to demonstrate the point. In the real world, if the fiscal deficit is a large percentage of GDP then it might take some years to start reducing the public debt ratio as GDP growth ensures.

So even with an increasing (or unchanged) deficit, real GDP growth can reduce the public debt ratio, which is what has happened many times in past history following economic slowdowns.

The best way to reduce the public debt ratio is to stop issuing debt. A sovereign government doesn’t have to issue debt if the central bank is happy to keep its target interest rate at zero or pay interest on excess reserves.

The discussion also demonstrates why tightening monetary policy makes it harder for the government to reduce the public debt ratio – which, of-course, is one of the more subtle mainstream ways to force the government to run surpluses.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2017 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Re Question 1

Doesn’t private sector having more money to spend have the potential to increase aggregate demand?

(This is hypothetical on my part. I put it out looking for corrections.)

I think what we’re being told is that, under modern conditions, government borrowing doesn’t reduce the amount the private sector has to spend. Money spent in the private sector is presently created wholly by bank lending, and the banks lend as much as they can possibly expect to be repaid (or beyond, as we’re seeing in Italy.)

Mel, I think MMT (and even mainstream economists) tell us that the currency issuing government can always create money, so at the very least, not all money spent in the private sector is created by bank lending. Where MMT differs (in my understanding) is that MMT holds that government deficit spending by a sovereign currency issuer is not actually ‘financed’ by government bond sales. Instead, the deficit spending in reality creates new money that flows to the private sector which then can either spend it or save it. The debt created if the government wishes to issue bonds to match the spending is better thought of as a monetary policy choice and does not realistically limit the spending desires of the private sector in any way.

As far as banks creating money through lending, the MMT understanding is more complex (and in my opinion more accurate) than the mainstream idea that banks mostly serve as intermediators between borrowers and savers. MMT holds that banks are in the business of loaning to credit-worthy people and organizations and will do so pretty much whenever they can, because that is how they make money and stay in business. MMT holds that a bank loan creates a bank deposit pretty much out of thin air because the bank knows that, if necessary, it can access the funds needed to cover a good loan from other banks or from the central bank. And for the duration of the loan, this is for most intents and purposes newly created money, and newly created effective demand. And one of the effects of this money creation by banks is that most of what people actually use as money happens to have been created by banks through the loaning process. And MMT is hardly alone in understanding bank loans this way. The people at the US Fed understand this and the people at the central bank of the UK also do and have written about it.

Please realize that the above is based on my understanding of what Bill Mitchell and MMT say, and that it is certainly subject to correction, because it may need it:)

Jerry, can we really work out how much money in circulation IS from a bank loan and how much from (as MMT would see it) ‘new’ money from Government spending. Positive Money and others say that 97% of our money is bank loan originated yet if Government money is new money ( net asset) then that adds to the stock. Isn’t this further complicated by the fact that the bond sales go partly to foreign buyers ( circa one third to China for the UK) so that won’t soak up money from the domestic system. From this is seems to me that money in circulation (at time ‘t’) would be G(at time ‘t’) -domestic bond sales + bank loans at time ‘t’.

The above might be nonsense -just trying to think it out!

Simon, I don’t know the answer to your question. What I do believe is that MMT says that any spending by the currency issuing government creates money, usually in the form of bank deposits. Any taxing destroys money. MMT holds that the bond issuance that might accompany deficit spending is mainly an asset transformation- the financial assets are created by the government spending and a government bond is just a different form in which they are held by the private sector. I don’t think it matters much whether the bonds are sold to domestic or foreign buyers as long as they are denominated in the currency the government issues.

I think that for an economy (including the foreign sector), the private sector net financial asset balance will equal the sum of all previous government deficits i.e. the national debt. How much of this is “money in circulation” depends a lot on which financial assets you decide to include as being money. It seems to me that given the liquidity of the market for government debt in a country like the US, almost all Federal government debt might as well be classified as money. This may be why MMT holds that US bond issuance does not reduce the inflationary aspect of Federal deficit spending, but you would have to ask Professor Mitchell about that.

As far as money creation by banks, I am not confident that I understand it. So far as I do understand, a bank loan creates a bank deposit, which is usually classified as ‘money’, but does not affect the financial asset balance of the private sector- so it does not create ‘net financial assets’ for the private sector.

As I understand it, bank loans do create ‘money’ and they do allow for an increase in aggregate demand at the time of their issuance, and depending on the policies of the central bank, they do not necessarily detract from anyone else’s ability to spend. So they are not at all like what would happen if I lent you 100 dollars. In that case, you could increase your spending by $100, but I would be unable to spend.

I think you could say total accumulated government deficits basically corresponds to outstanding government debt which is the same as all net financial assets in the private sector. Credit money by the banks is a zero-sum game in this respect(loanable funds theory). Credit creates deposits but the government(a part from deposits)creates new money(bank reserves)by running deficits. Money supply is measured as check- or short-time deposits while longer durations like government bonds/bills are not part of i.e the M2-measurement.

Bank credit is the main driver of demand/investment/income in the private sector. A government balanced budget is mostly redistribution but with the objectives to create incentives to stimumulate demand through taxes. Running deficits on the other hand is about creating new demand utilizing i.e unused resources like unemployment.

US Money supply M2 is 13,5 Trillion dollar. Total (net)credit of all commercial banks 12,6 Trillion. US Monetary base 3,8 Trillion but main part are excess-reserves created through QE. US Government debt 20 Trillion dollar. 40% of US government debt-stock is placed outside the US but these interest-bearing dollars are still at the US Fed Bank.

Banks normally have only a small part ot their balance-sheet as cash-reserves at the FED due to i.e the lower interest-rates(excluding QE-excess-reserves). In practice (US)reserve-ratios are upheld by borrowing in hindsight. Net financial assets means new assets…..cash or whatever. But because government deficits normally means that that the FED wants to reduce/take away newly created reserves as a part of their monetary policy(inflation and Fed Funds-rate) new financial assets “becomes” government debt, aka bills/bonds instead of cash. Still remember bills/bonds are also reserve-money. From the private-sector perspective the newly created money are deposited at the bank and probably as a monetary supply aggregat. i.e M1 or 2. When a new bond or bill is issued the banks buy them and sell all or part of them to the public(private and public-sector) which then lowers the money supply. If there was no need for a monetary policy and an interest-rate floor bankreserves would increase and interest-rates decline. Bankcredits could partly be offset by government deficit-money but in the long run bankcredit money would expand “as usual” because banks doesn´t really need reserves to create deposits. But with larger reserves(i.e government deficits) maybe the interbank-market would shrink some.

Does Positive Money know what they are talking about when they say 97% of all money is created by banks. I haven´t yet seen a factual explanation except the calculation with my reference 8:16 above: 12,6/13,5=93%(bankcredit of moneysupply). Another 20 Trillion(IOUs) have been created by the government and the same amount have been deposited at some time at the banks. In total that is 12,6 + 20 = 32,6 Trillion dollars. Who can say who has bought the 20 Trillion IOU´s? Was it originated from money created by banks or by the government? Or maybe from the foreign sector(i.e. European banks)?

Christer Kamb, a few questions-

I do not disagree with your statement about how the money supply is typically measured, but would you agree that the measurement is somewhat arbitrary? Perhaps borderline useless?

Would you agree that the main driver of ‘aggregate demand’ even in a wealthy country is actually the demand for necessities such as food, clothing, housing, transportation, beer, etc.? Bank loans might facilitate the provision of some of these (not beer so much) but can they be said to be the driver of that demand?

Why rely on the loanable funds theory to explain anything, especially bank lending? In my understanding of the loanable funds theory it does not even describe the behavior of individuals let alone banks or governments.

Jerry; I think I so far agree with the MMT description of how the monetary system works. Yes M-statistics is maybe mainly for centralbankers and other economists believing in the Quantative theory of money. Otherwise ex post as accounting variables.

When we talk of aggregate demand we usually mean constant real growth on a margin(unchanged demographics). The basic needs you refer to are not the drivers here I think. For long term growth you need investments and banks are the facilitaters(intermediaries in some models). The wealth of a nation etc is what can be produced….and consumed. Without investments production will stagnate and so will probably income and consumtion. Bankers are the main drivers because of their relative competence. Unfortunately neo-liberal policies during 30 years have let collective assets greatly depreciate due to budget constraints and missunderstandings about government currency capabilities. Sooner or later the MMT-perspective will prevail. I am sure! Unfortunately there can be a another financial crises or war before this will happen.

I mentioned Loanable Funds only to describe that ones debt is another persons asset(zero-sum). No new financial assets are created. Instead mainstream-economists, as you imply, undervalues the risk of mal-investments by the banks(poorly regulated regarding capitalreserves in Europe i.e).

Thank you for replying Christer. I still do not agree that banks are ‘drivers’ of demand but would characterize them as ‘facilitators’ that enable potential demand to turn into actual effective demand.

As far as real per capita growth in an economy, I want to ascribe that to investment undertaken by people who notice a potential to improve how products or services are currently produced. And to my belief that people in any industry will generally start off with the advantage of knowledge from the past and will almost always attempt to improve upon it. But either way, banks are mostly facilitators of investment rather than drivers of it. The banks, and the system they operate in, enable investment spending, (and consumption spending often), but they do not cause it.

Jerry,

Just to throw a small spanner in your works, whilst I agree with your basic thinking, there are cases of where banks do increase aggregate demand. At the moment there is a growing problem, that may cause the next crash, with auto loans. The banks make these loans easy to get so it is bound to increase demand for cars. Same thing went for sub-prime real estate mortgages.

Thank you for commenting Jerry. English is not my native language. I meant bankcredit is the driver, not banks per se. Banks before government. Yes I fully agree investors/risktakers are the real drivers behind growth. Governments are also investors in our collective “infrastructure” of education, welfare and communication/transportation etc.

My biggest interest from MMT derives from their explanation of how the monetary system works and how government deficits can be used to create new money/demand from thin air by utilizing unused resources like unemployment. I don´t like ideas from other direction like Basic Income or State Money to replace commercial banks.

Nigel Hargreaves and Christer, I am not really disagreeing with you. I just think it might be better to view bank loans as a means of transforming the potential demand that is already exists into effective demand that can purchase the goods or services. Effective demand will increase aggregate demand, so bank loans play a part in that. The fact that a bank might give me a loan to buy a new car is not going to make me buy a new car if I don’t want one, but it might enable me to do so if I did want one, but just couldn’t pay for it right now without a loan.

Nigel, unless people are buying new cars on credit with the intent to sell them later at a higher price, I don’t see how auto loans could crash the economy.

Jerry-I think Nigel is referring to the rise of so-called PCPs (Personal Contract Purchase) . I’ve noticed , here in the UK, that the number of SUV’s on the road seem to be increasing exponentially. The purchases seem to be thought of as the ‘new sub-prime’. The value of car loans in the UK almost trebled to £31.6bn between 2009 and 2016:

See: http://www.theguardian.com/money/2017/feb/10/are-car-loans-driving-us-towards-the-next-financial-crash

Bill Mitchell; Regarding Question 1

You said;

“What would happen if there were bond sales? All that happens is that the banks reserves are reduced by the bond sales but this does not reduce the deposits created by the net spending. So net worth is not altered. What is changed is the composition of the asset portfolio held in the non-government sector.”

Before your quote above it was crystal clear. Last sentence above about portfolio-composition is also clear to me. I agree. Bondsales must take away cash from banks deposits at the centralbank (reserves)when banks buy these bonds. BUT if banks then resell the same bonds to their customers then customer-deposits at the bank will be reduced. This latter transaction is only about changing hands of the bonds. Reserves are not affected. BUT M1 will fall with the same amount. Private-sector worth is unchanged. Spending-power(M1) in the economy(bank-customers)is also unchanged when measured against a situation before the deficit-spending by the government.

Do you agree on this?

Simon; Strange article I must say.

1. No mention about the size of the car-lease-loans i UK but they refer to the US(1,1 Tn USD).

2. No facts how these leasing-contracts looks like. Monthly payments during 3 years. OK! It would be normal to pay interest and depreciation(3 years) down to let´s say 40-50% of the cars new-sales value(if new when leased). Yes if the lease-taker choose to buy the car after 3 years then this value should/could be fixed in the contract. If the lease-taker returns the car after 3 years it is not unnormal to pay for deviation from estimated marketvalues year 3 in the leasing-calculations.

3. The article refers to ABS securitization but no data how big this business is and how it is done?

4. The GFC had it´s origin in the repo-market. Rehypothecation of RMBS(ABS) that broke down totally. Are these lease-contracts outside of the unknown ABS-sizes collateral in the interbank-market?

Hard to see a new financial crash due to car-loans but together with a second housing-downturn and a general private debt-crises it could mean big trouble for aggregate demand.

Simon, in regards to your comment at 8:31- All I can say is that I do not know why people are suddenly buying or leasing cars, if that is what is happening.. If they were doing so in some speculative manner expecting that they could sell the car (or even more idiotically, the lease) for more money later, then I would be concerned about their sanity and the economy in general if it was widespread enough. But otherwise it would be just a normal course in the business cycle. It increases aggregate demand right now, and it might decline later and be a part of a decrease in demand that leads to a normalish recession. Which MMT tells us how to mitigate.

But this stuff is far beyond my competency to comment on here. I am only trying to be helpful about some questions about MMT that I have learned through reading Bill Mitchell. I do like to argue and debate though. 🙂