The other day I was asked whether I was happy that the US President was…

Portugal demonstrates the myopia of the Eurozone’s fiscal rules

On March 24, 2017, the Portuguese government (via Instituto Nacional de Estatística or Statistics Portugal) sent Eurostat its – Excessive Deficit Procedure (1st Notification) – 2017 – which is part of the formal process of the EU surveillance on the fiscal policy outcomes for Member States. The data submitted to the EU showed that the Government had reduced its fiscal deficit from 4.4 per cent in 2015 to 2.1 per cent in 2016, thus bringing it within the Stability and Growth Pact rules (below 3 per cent). However its public debt to GDP ratio rose modestly over that time from 129 per cent to 130.4 per cent. The other stunning fact presented, which hasn’t received much attention in the media, was that government spending on gross fixed capital formation fell from 4,049.3 million euros in 2015 to 2,879.6 million euros in 2016, a 29 per cent decline. Further, real GDP growth has been positive for the several quarters now and this has boosted tax revenue. The popular press has been claiming this is a Keynesian miracle – spawning growth and cutting the fiscal deficit. There is some truth to the statement that the ‘Socialist’ government has reversed some of the worst austerity policies introduced by the previous right-wing government, acting as puppets of the Troika. But what has been going on in Portugal highlights the myopia inherent in the restrictive Eurozone fiscal rules, which promote very short-term behaviour on the part of the Member State governments. As Portugal is currently demonstrating, it is prepared (and is motivated by the fiscal rules) to sacrifice sustained prosperity for short-term appeasement of Brussels. Short-term growth can occur within limits at the expense of long-run potential.

Growth returns to Portugal

The following graph shows real GDP growth (Quarterly and Annual) from 1996 to the December-quarter 2016. Two things stand out: (a) average growth has been much lower since Portugal adopted the foreign currency (the euro); (b) after the debilibitating double-dip recession, some stable, albeit modest, growth has returned.

The data tells us that when the crisis started to undermine growth (first in the June-quarter 2008) it was mainly household consumption spending and private investment spending exacerbated by on-going external deficits that failed. At that time, government spending was providing fiscal support to the economt.

Then the Brussels Groupthink stepped in and after recording 6 successive quarters of growth with domestic demand on the improve (with fiscal support), the economy went back into recession in the December-quarter 2010 and posted negative growth for the next 8 quarters – a lengthy recession.

During that second episode, the contribution of government spending to growth was systematically negative (the austerity effect), which undermined household consumption and private investment spending.

It was an act of sabotage.

In the more recent growth phase, investment spending remains weak. and the modst growth is being driven largely by household consumption expenditure with some modest support from recurrent public spending.

But such was the severity of the downturn (Portugal lost, at its worst, 9.6 per cent of the size of its economy – by the December-quarter 2012) as a result of the harsh austerity that was imposed under orders from Brussels (taking orders from Washington, in part) that even though there has been a some modest growth since the end of 2014, the economy is still 4.1 per cent smaller than what it was in the March-quarter 2008 (the last peak).

In other words, the Portuguese economy has still not regained the position it was in when the crisis struck.

1. Total consumption expenditure is still 3.6 per cent below where it was in the March-quarter 2008 (households minus 3.2 per cent; government minus 6.4 per cent).

2. Overall capital formation (investment) is down 32.2 per cent (a radical drop), with public capital expenditure falling significantly in recent years.

3. Domestic demand (spending) is down 9.8 per cent overall.

4. Export spending is up by 33.2 per cent. Net exports have made a positive contribution to growth in 5 of the 11 quarters since the June-quarter 2014, when sustained growth returned.

So the lingering recession effect should be borne in mind when the cheer squads come out in favour of Portugal. It has been an unmitigated disaster and remains in a parlous state.

The labour market and population disaster

The lingering recession effect is very evident in the labour market, where the overall population has shrunk (due to net out migration in search of better opportunities) and elevated levels of unemployment are entrenched.

In the June-quarter 2008 (the peak employment quarter before the crisis), Portugal’s 15-64 year old population was 7,037.1 thousand people. It has steadily slumped since then and in the December-quarter 2016 was just 6,678.2 thousand, a decline of 5.1 per cent.

Even with that decline in population, the Employment-to-Population ratio has fallen from 68.5 per cent (at the peak) to 65.9 per cent in the December-quarter 2016.

Total employment is still well below the June-quarter 2008 peak of 4,818.1 thousand. In the December-quarter 2016, it was estimated to be 4,400.5 thousand, a decline of 8.7 per cent.

The labour force has shrunk almost proportionately with the shrinking population given the participation rate is only 0.3 points below the 74.2 per cent recorded in the June-quarter 2008.

Taken together, unemployment has risen by 34.3 per cent since the June-quarter 2008, to 537.4 thousand, with the unemployment rate rising from 7.7 per cent to the December-quarter 2016 estimate of 10.9 per cent.

So there is nothing good about any of that.

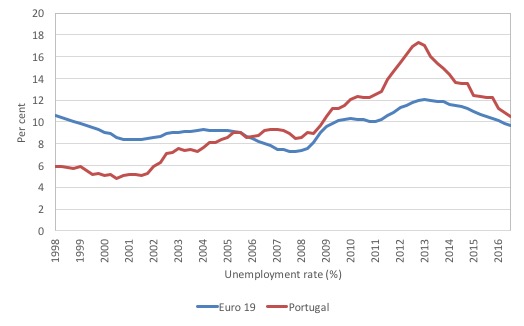

The following graph shows the movements in Portugal’s unemployment since the June-quarter 1998 to the December-quarter 1998 (red line) and the Eurozone 19 unemployment rate over the same period.

It defies reason to suggest that recent history is acceptable. The proponents of the Eurozone point to the declining unemployment rate since mid-2013 as a sign of success. The fact it reached 17.3 per cent in the March-quarter 2013 is a sign that the system is a failure. The additional fact that it remains at 10.5 per cent and well above the pre-GFC levels reinforces that conclusion.

From an employment perspective, the situation is even more dire.

The following graph shows total employment for the Eurozone 19 and for Portugal from the June-quarter 2008 (the peak = 100 in index points) to the December-quarter 2016.

Portuguese employment is still 8.6 percentage points below the level it reached at the onset of the crisis, while the Eurozone overall is 0.4 points below. That is, the Eurozone still has an overall employment loss after more than 8 years and Portugal’s employment is a long way from regaining its pre-GFC level.

Had not Portugal’s net out migration been so significant, the situation would have been much worse than it already is.

A simple simulation is instructive. If the modest average population growth between the June-quarter 1998 to the June-quarter 2008 had have continued then Portugal’s population would have been 7,220 thousand in the December-quarter 2016, as opposed to the actual value of 6,678.2 thousand – that is, 541.8 thousand more people.

In that scenario, the Employment-to-Population ratio, currently at 65.9 per cent, would become 60.9 per cent, some 8 percentage points below the June-quarter 2008 peak – a huge drop.

In that case, the unemployment rate would be 17.6 per cent rather than 10.9 per cent.

So the loss of working age population has attenuated the domestic implications of the disaster.

I need not add that those who are most likely to leave the nation in these types of situations are more likely to be among the higher skilled and best educated workers (and the younger prime-age) who more easily access opportunities elsewhere.

Earlier this month (April 1, 2017), the Economist Magazine published an article – Growing out of it: Portugal cuts its fiscal deficit while raising pensions and wages. It carried the by-line “The Socialists say their Keynesian policies are working; others fret about Portugal’s debts”.

As the earlier discussion suggests, we should rather be fretting about the people who live and want to work in Portugal rather than wha the banksters who might be holding the debt think.

The Economist article is very strange.

It claims that Portugal’s Socialist prime minister, António Costa has “kept his word” to “to reverse the austerity measures attached to Portugal’s bail-out during the euro crisis and to meet stiff fiscal targets.”

They point to the reduction in the fiscal deficit, which they erroneously claim to be the “lowest since Portugal’s transition to to democracy in 1974”. In fact, the right-wing Social Democratic Party administration of Aníbal Cavaco Silva in the XI Constitutional Government of Portugal recorded the same deficit outcome in 1989 (ironically, mostly due to the increased operational efficiency of public trading enterprises).

The current fiscal outcome is according to the Economist “the first time that Portugal has complied with the euro zone’s fiscal rules”, which is also not quite correct. For the first-two quarters of 2008, Portugal recorded fiscal deficits below 3 per cent but those were soon swamped by the cyclical effects (automatic stabilisers) that came with the crisis.

Further, Portugal has never come close to satisfying the other SGP fiscal test being the 60 per cent public debt threshold. Its public debt ratio currently stands at around 130 per cent, and the European Commission just turns its head on that reality, although when the next crisis comes (and it is building now), it will be that figure that resonates strongly as bond markets abandon Portugal and the ECB has to, once again, keep the monetary union afloat by flouting the ‘no bailout’ rules embedded in the Treaty, just as it has been doing since it introduced the Securities Markets Program in May 2010.

The Economist article waxes lyrical about the fact that Portugal has recorded a fiscal outcome below 3 per cent while maintaining economic growth.

Apparently it is “proof that their Keynesian approach to growth works”.

Well not quite (again!). What has been happening in Portugal is not quite what I would call a ‘Keynesian’ stimulus.

It is true that the government has stood by its left-wing credentials and reversed some of the worst austerity attacks on welfare that the previous right-wing, pro-Brussels government had implemented (as puppets to the Troika).

So it has increased public sector wages (restoring the 30 per cent cut since 2009) and

But don’t be too fooled. It has also increased indirect taxes significantly (VAT and excises, including petrol and tobacco, and real estate) and cut spending in many areas (more than €1 billion taken out from the spending stream).

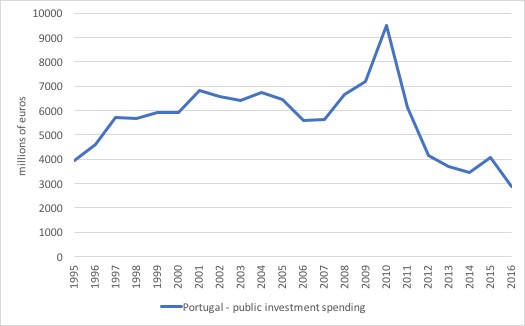

More strikingly, it has savaged public investment spending, which undermines the long-run future of the nation.

Here you see the myopia of the whole Eurozone approach.

There is some flexibility within the Stability and Growth Pact rules, given that fiscal deficits can come in at just under 3 per cent and pass that part of the test (the other test being the 60 per cent public debt threshold, which Portugal has no chance of ever coming close to satisfying).

But what the restrictive Eurozone fiscal rules promote is very short-term behaviour on the part of the Member State governments.

As Portugal is currently demonstrating, it is prepared (and is motivated by the fiscal rules) to sacrifice sustained prosperity for short-term appeasement of Brussels.

I say that because even though government consumption spending (recurrent) is providing some modest support to growth, it has cut capital spending signficantly.

Total public expenditure fell consistently during 2016 (not a Keynesian act when unemployment is so high) mostly due to cuts in the capital outlays.

Gross public capital outlays fell from 2.3 per cent of GDP in 2015 to 1.6 per cent of GDP in 2016.

The following graph tells the story.

Further since 2015, increased tax revenue has contributed much more to the annual change in the fiscal balance than expenditure cuts.

The Portuguese Public Finance Council data shows that the changing contributions were:

1. 2015 Revenue +366 million euros, Expenditure -51 millions euros

2. 2016 Revenue +700 million euros, Expenditure – 239 million euros

It might hope that by stimulating short-term domestic demand it will tease out private investment and grow productive capacity that way. And it is true that private investment contributed to growth in the last quarter of 2016.

But how long that will continue is anyone’s guess. An additional point worth noting is that investment from EU funds has helped stimulate private investment, which reinforces the point that a strong fiscal capacity at the European level would be desirable. But these interventions are not systematic and are finite.

There are some clouds hanging over the nation – not the least being its banking sector.

While public expenditure has been cut major outlays have been absorbed in trying to shore up the failed banks. That process is unfinished and will absorb additional public funds.

Conclusion

So, how long Portugal remains within the Excessive Deficit Procedure rules of the EU is unclear – I predict not very long.

Any further cuts will start to undermine growth and reverse the gains in tax revenue. But to make ‘space’ for the bank protections and remain withint the restrictive SGP rules, something will have to give.

I predict the fiscal bottom line will give and then the political or ideological tension between Brussels and the ‘Socialists’ in Lisbon will come into play.

I do not think Brussels will be as forgiving of Portugal as they have been of Spain’s continued violation of the rules. But then Brussels was trying to ensure the PP was elected in Spain so they need to allow on-going growth on the back of rising fiscal deficits.

But in Portugal, the ‘Socialists’ are Brussel’s worst nightmare.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2017 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Bill – I assume when you typed: ‘Its public debt ratio currently stands at around 30 per cent’ you meant ‘130.’ Which I think is the latest figure for debt’GDP in Portugal?

Excellent and informative blog as always.

I took a vacation in Portugal in the height of the crisis. I was shocked at the brutality of the austerity measures: highway tolls that had vacated them from automoviles (so self-defeating), impossible food prices due to VAT rates, etc… Most shocking was finding out that I was actually renting out an engineer’s house who had to move his family out during our stay. Of course the Costa government seems like an improvement on the previous brutal right-wing government but I agree with Bill: this recovery has very short legs and it has left a good portion of the population without future.

” it has savaged public investment spending, which undermines the long-run future of the nation”

cutting long term investment will in the long run undermine it domestic economic capacity,so when they are caught out by the next crisis-they will be even more import reliant.And fearful of leaving the Euro as a result.

Hopefully they can look at the Brexit and see the sky has not fallen in, neither has Britain sunk beneath the waves, which should add to the reasons to exit the ECU.