I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Recessions are never desirable events and are always avoidable

Bloomberg published an article last week (April 7, 2017) that it should not have published given that the article offers only fake knowledge to its readership. The article in question – Australia’s Delayed Recession Fallout Is Showing Up in Its Jobs Data – carried the sub-title “There may be trouble ahead” and purported to argue that because the Australian government’s fiscal stimulus allowed our nation to avoid a recession in 2009 we now have to ‘pay the piper’ and take our medicine and suffer a recession anyway. The proposition is ridiculous to say the least. The article uses as authority some nonsensical statements from a “business management consultant”, who doesn’t appear to have a very sound grasp of either history or what is actually going on. This is another case of misinformation. The fact is that the Australian government’s fiscal stimulus in 2008 and 2009 saved the economy from recession. The current slowdown and parlous labour market is not some delayed effect from that. Rather, it is because the Australian government caught the ‘fiscal surplus bug’ obsession, and began a misguided pursuits of surpluses, irrespective of what the external and private domestic sectors were doing. It caused an immediate slowdown and all the virtuous dynamics that were accompanying the stimulus-led growth (for example, fall in household debt and the rise in the household saving ratio) were reversed, as we would expect. Far from being delayed effects, the poor jobs data is because current fiscal policy is too restrictive. Simple solution: expand the discretionary fiscal deficit (preferably with a large-scale public sector job creation strategy).

The article tenet is that:

Australia’s success in evading the global recession is coming back to haunt it.

Suggesting that if we had have taken our medicine when everyone else did – you know massive elevation in unemployment, increased poverty rates, huge loss of national income – then the ‘ghosts’ would not have appeared now to give us grief.

It focuses on the rise in underemployment in Australia – as the sign that the ‘ghosts’ are in operation.

The ‘cleansing’ hypothesis

The Bloomberg article quotes some ‘business management consultant’ as saying:

You can’t escape the fact that recessions do have some positives: the crudest way to put it is it cleans the crap out of the system … It resets your cost base, it improves efficiency, productivity and on an even more fundamental basis, it gives people perspective.

This is an old contention – it has been referred to as the “pitstop” model of recession in the literature.

The contention is that recessions are associated with ‘cleaning up’ or in other terminology as ‘taking a pitstop’ a term introduced in Blanchard and Diamond’s 1990 paper – ‘The Cyclical Behavior of the Gross Flows of U.S. Workers’.

They claimed that during recessions “changes in employment are dominated by movements in job destruction rather than in job creation” (meaning people are still hired during recession but many more are shed).

They said this leads to a view of “recessions as times of cleaning up”.

[Reference: Blanchard, O.J. and Diamond, P. (1990) ‘The Cyclical Behavior of the Gross Flows of U.S. Workers’, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 2, 85-155.]

The problem with this view is that it doesn’t sit well with other cyclical data movements.

In recessions, firms make a number of decisions in order to survive. They are typically already using plant and equipment which is marginal in terms of costs and long-term profitability. They shut down that capital during a recession because they know that when the investment cycle improves the higher unit cost production techniques embodied in that capital will not be viable.

So whether a firm goes bust altogether (and sheds its workers) or just focus production on their most profitable plant depends on that assessment.

But which workers do firms lay-off if they determine they will continue to operate?

The most vulnerable are those who have skills specific to the unprofitable plant and equipment. They tend to go first. The firm also have workers who they would like to retain but who are too expensive given the fall in demand for their products. The hope is that they be able to rehire them after some temporary layoff.

But other workers (arguably the majority) are intrinsic to the on-going function of the firm and they have to be retained. For example, a firm requires a reception capacity and some sales persons. These workers clearly might not work as hard during a recession as they do during more normal times.

They are, however, retained and reassigned to various duties (maintenance and cleaning, file sorting out etc) while the recession passes.

As a consequence, output per hour falls during recessions.

The “pitstop” model of recession suggests that managers take time during recessions to streamline their processes.

Martin Baily (in commenting on the Blanchard and Diamond “cleaning up” idea) said that:

… the data did not accord well with a “cleaning up” or”pitstop” model of recessions … productivity fell during a recession, contrary to what would be expected if managers were streamlining their production process.

At the time, this “pitstop” analogy was used, another economist (commenting on the same paper) said that the “lack of a spike up in employment after a recession hurts the pitstop metaphor since after a pitstop people get going right away.”

Further, George Perry (in the same commentary) argued that:

… during recessions many people switch from long-duration jobs to temporary jobs, resulting in a greater proportion of the work force in short-duration jobs. If the amount of job creation and destruction is relatively constant in the temporary jobs, then the destruction is taking place in the long-duration jobs. This view provides a harsher picture of what happens during a recession than one would get if the change in job composition were ignored.

This is consistent with the view that recessions are deeply inefficient events not akin to a new birth.

In another paper (from the NBER Macroeconomics Annual 1991, Volume 6), in commenting on Robert E. Hall’s contribution (Labor Demand, Labor Supply, and Employment Volatility) where Hall advanced the ‘cleaning up’ hypothesis for another time, Martin Baily concluded that, quit rates fall dramatically during recessions as do hiring rates.

He also noted that “Labor force participation decreases and the number of discouraged workers increases”, which does not accord with the idea that the demand side of the labour market is clearing away the debris and welcoming in the new better skilled workers.

He also said that:

In terms of social efficiency, I am persuaded that recessions are inefficient. Better coordination of economic decisions would increase aggregate employment, output, and welfare … The expectation of falling output and employment generates further declines in output and employment, and the economy can move to a temporary equilibrium with low production and sales … In recessions, firms would like to produce and sell more even with no changes in prices. They are not deciding to produce less because reorganization is so profitable

Which is the observation that John Maynard Keynes made years before – that an economy can become stuck with high unemployment unless there is a government intervention in the form of the fiscal stimulus to ‘kickstart’ recovery.

Not only does productivity decline during a recession but employment also recovers very slowly following the trough.

That is, there is persistence and asymmetry in the response of employment over a cycle. Growth declines sharply and is typically weak for some period into the recovery.

None of these characteristics of a recession support the view that there is a cleaning up going on during a recession.

Sure enough high cost firms go broke and disappear as does their capital. That only means that by the time the recovery is stable, the average vintage of the capital stock is lower and probably the cost structure of firms is lower.

But it is clear that growth builds on itself. When private spending is stagnant and expectations are very pessimistic what external force will change that? Why will investors once again assume the risk and start building new capacity?

In some of my earlier work (with Joan Muysken) – for example, here is a working paper you can get for free (subsequently published in the literature) – we developed a model based on the notion that investors facing endemic uncertainty make large irreversible capital outlays, which leads them to be cautious in times of pessimism and to use broad safety margins.

Accordingly, they form expectations of future profitability by considering the current capacity utilisation rate against their normal usage. They will only invest when capacity utilisation, exceeds its normal level.

So investment varies with capacity utilisation within bounds and therefore productive capacity grows at rate which is bounded from below and above.

The asymmetric investment behaviour we observe in most nations thus generates asymmetries in capacity growth because productive capacity only grows when there is a shortage of capacity.

Our theoretical ‘model’ stands up very well against empirical scrutiny and is at odds with the idea that there is a robust cleansing going on during recessions that is beneficial.

Recessions are periods of stagnation and massive losses which impact on workers and their families the most and have long-lived effects.

The ‘expert’ used by the Bloomberg article doesn’t seem to be aware of this long history of research into the impacts of recessions.

Was the fiscal stimulus the source of today’s slowdown?

The article then tries to implicate the fiscal stimulus is the current slowdown and high underemployment in Australia.

The journalist writes:

Australia deployed fiscal and policy stimulus to avoid economic contraction after the collapse of Lehman Brothers Inc.; and China’s massive stimulus program then sent commodity prices soaring, underpinning the economy’s roaring back Down Under. The upshot: all that good work only delayed the effects of the recession rather than completely avoiding them.

The evidence cited:

1. “over the past year as full-time jobs fell, part-time roles picked up some of the slack and many people quit hunting for work.”

2. “a labor market that in reality has a lot more slack than” the official unemployment rate would suggest.

The ‘business management consultant’ apparently the only source consulted by Bloomberg waxed lyrical by claiming that:

Everyone thinks that we’ve done really well since the global financial crisis, which we kind of have, but a lot of the fallout from the GFC has just been kind of delayed or slowed in Australia, whereas in other places it hit pretty hard, they hit rock-bottom, then they’ve recovered from that.

The Bloomberg characterisation of this observation is that “The issue then is whether Australia might’ve done better taking its medicine earlier and getting it out the way.”

This claim is supported by the observation that “The lack of an economic reset has left the country with exceptionally high household debt — almost 189 percent of income — and stratospheric property prices on its east coast.”

But the causation in all these claims are astray.

First, which nations have “recovered”? And what have been the policy support structures in place?

The Eurozone is not in a situation where we would say it has recovered.

The unemployment rate was 7.3 per cent going into the crisis (2008Q1) and peaked at 12.2 per cent (2013Q2) and remains at 9.7 per cent. Hardly a recovery.

Greece went into the crisis with an 8 per cent unemployment, it peaked at 27.7 per cent and remains at 23.4 per cent.

I could go on.

Where the unemployment rate has come down significantly, fiscal deficits have remained at elevated levels with no harsh austerity.

In terms of lost GDP, the Eurozone only just returned to its peak March-quarter 2008 level in the September-quarter 2015 and is still only 2.4 per cent above that 2008 level as at the December-quarter 2016. That is not what we call a ‘recovery’.

Moroever, trying to link the current malaise in Australia to the fiscal stimulus in 2008-09 is ignorant of what has happened since the stimulus.

First, as I explained in this blog – Amazing what politics does to people – in late 2008 and early 2009, the Federal Labor government in Australia introduced a significant fiscal stimulus program encompassing cash handouts to stimulate immediate consumption and two large infrastructure initiatives (school building enhancement and insulation in all homes).

It worked virtually immediately as it was designed and while the rest of the world was falling into the morass of recession, Australia barely noticed the GFC.

It was a very sound intervention from a macroeconomic perspective even though the design of the programs did not yield enough jobs per dollar spent and the stimulus wasn’t large enough.

The Chinese fiscal stimulus also saw our terms of trade rebound (for mining exports) after taking a dip downwards in the early days of the GFC.

Second, then the Labor Government caught the ‘fiscal surplus bug’ obsession, that infestation that turns sensible policy positions into misguided pursuits of surpluses, irrespective of what the external and private domestic sectors are doing.

In Australia’s case that was a very damaging bug to catch.

Acting on the ‘surplus disease’, the Australian government introduced the largest fiscal shift (towards austerity) in recorded history by cutting spending in real terms in the 2012-13 fiscal year by 3.2 per cent, which pulled 0.9 per cent of GDP out of public spending.

Revenue taken out by the government rose from 22.1 per cent to 23 per cent of GDP even though GDP growth was subdued.

This was an unprecedented fiscal shift.

At the time, Australia was nowhere near achieving full employment and non-government saving intentions, given the record levels of debt, were not being satisfied.

The combination of an external deficit (of about 4 per cent of GDP) with the need for the private domestic sector to save more overall, meant that a fiscal deficit that was even larger than was the case was required.

At the time, the Australian economy was languishing in low growth, with at least 14 or 15 per cent of its willing labour force not working and the private domestic sector was trying to reduce its massive debt levels.

The result – which was totally predictable – was that the economy took a nosedive, tax revenue fell even further and the fiscal balance moved further into deficit with unemployment rising.

The reversal in the fiscal balance was larger than the attempted contraction the year before (1.8 per cent increase in deficit compared to 1.7 per cent decrease the year before), which just tells you that it is folly to try to cut a deficit when private demand is weak.

Only the improving terms of trade saved the nation from disaster after the fiscal cuts.

From that period, Australia has struggled as the new Conservative government has tried to continue with the austerity push (with less success due to a hostile Senate and strong automatic stabilisers undermining tax revenue growth.

The weak aggregate spending as business investment has nose-dived with the end of the mining construction phase combined with the failure of the government to allow its deficit to rise sufficiently to cover the weak private spending has meant that employment growth has zig-zagged across the zero line for more than two years.

Wages growth is the lowest on record – and lagging well behind productivity growth.

And private consumption is once-again being propped up by credit growth leading to record levels of household debt.

But during the fiscal stimulus phase – 2009-2012 (approximately), things were quite different.

Real wages were growing modestly which was providing cover for household consumption to complement the support coming from the stimulus and the mining investment.

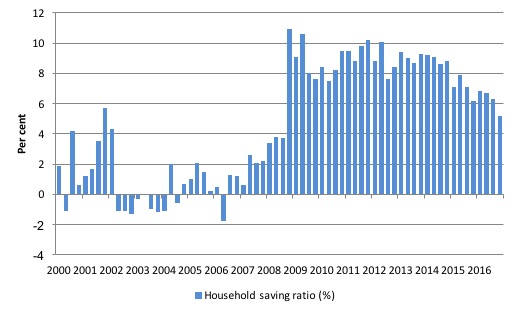

The following graph shows what was going on with household saving.

Prior to the crisis, household debt has sky-rocketed due to:

(a) the suppression of real wages growth due to labour market deregulation and the deliberate attack on trade unions;

(b) the financial market deregulation and the resulting credit push from the banks etc (a lot of which is now coming into the legal domain because of its corrupt tendencies); and

(c) the persistent fiscal surpluses squeezing household purchasing power. The surpluses were only possible because households propped up their consumption with debt.

After the GFC hit, the household sector sought to reduce the precariousness in its balance sheet exposed by the GFC.

Prior to the crisis, households maintained very robust spending (including housing) by accumulating record levels of debt. As the crisis hit, it was only because the central bank reduced interest rates quickly, that there were not mass bankruptcies and widespread housing foreclosures.

These bankruptcies are the type of “reset” the Bloomberg article thinks would have been desirable.

You can see from the graph, that the household saving ratio rose again aided by the fiscal stimulus, which was supporting national income growth.

Further, household debt fell from 180 odd per cent to 160 per cent and balance sheet restructuring was well underway. A ‘balance sheet’ downturn requires long-lived fiscal support for income to give the private domestic sector sufficient time to generate the savings necessary to pay down the debt.

In June 2012, the ratio was 11.6 per cent. Since the December-quarter 2013, it has been steadily falling as the squeze on wages has intensified and fiscal austerity has undermined growth.

The point is that if the fiscal stimulus had have been maintained for long enough to allow the private balance sheet restructuring to bring debt down significantly and for wages growth to match productivity growth, the labour market would not be in its current parlous state and real GDP growth would be up around trend.

Conclusion

It is never a good idea to allow a recession to occur in the hope that the “medicine” will deliver good outcomes. Recessions are always very bad events – some worse than others.

The Australian government did a great job avoiding the worst of the GFC but then undid its good work by falling for the austerity mantra.

Had the government allowed the GFC to take its course (that is, avoided a fiscal stimulus) then things would be much worse now than what they are.

The youth labour market, which is in an appalling state, would have been decimated.

Millions of Australians would have lost their houses and ended up with negative equity and owing the rapacious banks for an asset they no longer had the benefits of.

Business investment would have collapsed.

And while the property market is booming now, that is more to do with a defective tax system (that rewards speculation over occuption) and a failure to invest in social housing than it is in what happened to fiscal policy in late 2008 and early 2009.

The current malaise in the Australian economy is because private domestic spending is still not strong enough and the external sector continues to drain demand. In that situation, the fiscal stance is too restrictive (and has been since 2012).

These dynamics are exactly the opposite to what this stupid Bloomberg article purports to be the facts. It is a fake!

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2017 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

ITYM 2017.

And if the URL is anything to go by, it was published on the 6th.

Aidan; you are really nitpicking by pointing that small error out.

The real Australian problem is , legitimate tax havens in the form of negative gearing, tax-free super for the over-sixties and the other huge tax concessions for super for the elite 20% as far as assets and income are concerned.

The best way to drive cleansing is intense competition and a Job Guarantee to pick up workers from businesses that fail under competitive pressure.

You want ancient equipment, methods and skills to the retired as soon as possible, but at a rate of change people can cope with. Rate of change is like G force. A bit is exhilarating, too much is painful and then dangerous.

“It is never a good idea to allow a recession to occur in the hope that the “medicine” will deliver good outcomes.”

“90:18

is yet another example of central bank deception.

90:24

To create a public consensus

90:26

for the need for structural reform

90:28

by purposefully creating a recession

90:31

and then needlessly prolonging it,

90:33

must constitute an abuse of power.”

Princes of the Yen: Central Bank Truth Documentary

“In 1985, the Plaza Accord was signed, and a report named after former Bank of Japan Governor Haruo Maekawa was published. This report includes in it proposals for structural reforms that the current Koizumi Administration is intent on carrying out today.

But in order to realise these proposals, it was understood there would be much opposition from current power groups with vested interests. The author believes that the Bank of Japan elite chose the creation of the bubble and the consequent deep recession as the means to overcome this opposition.”

Fully agree with the basic thrust of the above article. I may be doing Bill an injustice here, but I think he has missed the basic flaw in the nonsensical “cleaning up” theory.

Strikes me the basic flaw is that it is totally unnecessary to have a recession in order to “clean out” unproductive jobs – or should I say “jobs which are becoming increasingly unproductive and which are almost certain to disappear at some point”.

Even if there are no recessions at all, there is a constant process of new and productive jobs appearing while unproductive ones are gradually discarded. All recessions do is to destroy the unproductive jobs earlier than would be the case given no recessions, and before those jobs become seriously uneconomic.

Austrians are particularly keen on the “recessions are good because they result in “clean up”” theory. What more evidence do we need that the clean up theory is nonsense?

[Off topic, but readers here may be interested.]

How Harvard flunked economics, Duff McDonald, Newsweek, April 8, 2017

The concluding “Reporter’s note” is of particular interest. The article is quite substantial with regard to negative historical claims involving Harvard, and the author is hardly an unknown, and yet repeated offers for comment by Harvard went rebuffed.

Which Austrians do you mean at the end of your comment, Hayek or Schumpeter? They can hardly be considered Austrians as they lived most of their lives in the USA.

” the clean up” is just another means of concentrating wealth in fewer and fewer hands.

As far as productive jobs are concerned, why are people still working 40 or more hours a week, when some 40 years ago, the media was talking about a 20 hours a week; what a lot of hogwash and hypocrisy.

Dear Bill

Kodak went bankrupt recently. Was it badly managed? Probably not. It just faced declining demand due to technological change. Likewise, in a recession, many firms are confronted with a fall in demand for their services or products. If they go out of business, it has nothing to do with inefficiency but is simply the result of a recession-induced decline in sales. Technological change and fluctuations in demand are the main reason why firms go out of business, not inefficiency.

Firms always have an incentive to improve efficiency. If a firm has a staff of 12 people who do the work that 10 people could perform adequately, then it could increase profits by letting go 2 of its employees. It doesn’t have to wait for a recession to do that. If the owner of the firm prefers a larger staff and lower profits, well that is his right. Profit-maximization is not a divine ordinance.

Regards. James

“You want ancient equipment, methods and skills to the retired as soon as possible, but at a rate of change people can cope with. Rate of change is like G force. A bit is exhilarating, too much is painful and then dangerous.”

The problem Neal, is determining what is the acceptable pace of change and how it is implemented. It is easy to assume that these changes can be carried out effectively to general (grudging) acceptance but we have seen alarming outcomes so many times; in Britain, any post-war consensus was jeopardized when the government of the day felt obliged to tackle inefficiency across the rail industry. It was repeated on numerous occasions over the next half century.

I leave it to others to decide what where the ideological and/or economic motivations of each confrontation.

But they are very real nevertheless, and will continue to put a considerable burden on any government facing the challenge, irrespective of a JG.

In the UK, the housing bubble(s) have been going on Since the 70’s with one of the first around 1971 – Jame’s Galbraith pointed out in his book ‘The End of Normal’ that rates of return on other types of investment were falling and housing presented to the banks the last area of lending that could be milked to produce big returns.

In the UK it is housing that is the great ball and chain on economic life and is ruining peoples’ lives and causing immense stress as well as wealth transfer to a property owning class. The were ample opportunities for Government to control mortgage lending and buy-to-let manias, but successive Governments were supine in the face of market fundamentalism.

Given that 39% of the Tory Party have significant interests in property (even 22% of Labour!) they don’t want their rentier income streams interrupted.

@ James – firms might have an incentive, but they don’t always have the foresight or patience. They might have to invest to get to the stage where reducing headcount by two is feasible. The payoff might take 5 years before it bears fruit.

Therefore, they might in turn prefer to do nothing but amble along with cheap labour and inefficiency simply because they can.

I have no doubt the evidence supports the case made by Bill Mitchell. As also mentioned by Simon, the neoliberals are scamming the system to increase the share of the economic pie and most of the political class has been bought by them. The neoliberals use facts and argument not to clarify the truth but to pursue their selfish agenda much like a partisan politician or barrister.

My background is in manufacturing and my experience is that during recessions all non vital expenses are cut to the bone and this effectively means cutting R&D, training, hiring of needed personnel, abandoning new projects that would have improved productivity and product innovation, cutting maintenance, planning and keeping old less productive equipment and processes running on a shoestring. Productivity in the short term may improve but it is at the expense of future improvements which are postponed or abandoned. The nations that have avoided the recessions and have instead used this time to build new facilities and innovative products or services thus improve their relative competitiveness.

Bill Hawil, Austrians are called ‘Austrians’ because of the framework they espouse, not because of where they live.