Here are the answers with discussion for this Weekend’s Quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of Modern…

Saturday Quiz – July 18, 2015 – answers and discussion

Here are the answers with discussion for yesterday’s quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of modern monetary theory (MMT) and its application to macroeconomic thinking. Comments as usual welcome, especially if I have made an error.

Question 1:

If a national government constructs a road in Year 1 but then in Year 2 tears it up and relays it with the recycled road materials, the national income stimulus from the policy is only enjoyed in the first year.

The answer is False.

This question allows us to go back into J.M. Keynes’ The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money. Many Flat Earth Theorists characterise the Keynesian position as advocating useless work – digging holes and filling them up again. The critics focus on the seeming futility of that work to denigrate it and rarely examine the flow of funds and impacts on aggregate demand. They know that people will instinctively recoil from the idea if the nonsensical nature of the work is emphasised.

Living in Australia (one of the World’s largest primary commodity exporters) I am always bemused by the notion that digging holes and filling them up again is futile work. It seems to characterise our mining sector very well.

But that aside, the critics actually fail in their stylisations of what Keynes actually said. They also fail to understand the nature of the policy recommendations that Keynes was advocating.

What Keynes demonstrated was that when private demand fails during a recession and the private sector will not buy any more goods and services, then government spending interventions were necessary. He said that while hiring people to dig holes only to fill them up again would work to stimulate demand, there were much more creative and useful things that the government could do.

Keynes maintained that in a crisis caused by inadequate private willingness or ability to buy goods and services, it was the role of government to generate demand. But, he argued, merely hiring people to dig holes, while better than nothing, is not a reasonable way to do it.

In Chapter 16 of The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money, Keynes wrote, in the book’s typically impenetrable style:

If – for whatever reason – the rate of interest cannot fall as fast as the marginal efficiency of capital would fall with a rate of accumulation corresponding to what the community would choose to save at a rate of interest equal to the marginal efficiency of capital in conditions of full employment, then even a diversion of the desire to hold wealth towards assets, which will in fact yield no economic fruits whatever, will increase economic well-being. In so far as millionaires find their satisfaction in building mighty mansions to contain their bodies when alive and pyramids to shelter them after death, or, repenting of their sins, erect cathedrals and endow monasteries or foreign missions, the day when abundance of capital will interfere with abundance of output may be postponed. “To dig holes in the ground,” paid for out of savings, will increase, not only employment, but the real national dividend of useful goods and services. It is not reasonable, however, that a sensible community should be content to remain dependent on such fortuitous and often wasteful mitigations when once we understand the influences upon which effective demand depends.

So while the narrative style is typical Keynes (I actually think the General Theory is a poorly written book) the message is clear. Keynes clearly understands that digging holes will stimulate aggregate demand when private investment has fallen but not increase “the real national dividend of useful goods and services”.

He also notes that once the public realise how employment is determined and the role that government can play in times of crisis they would expect government to use their net spending wisely to create useful outcomes.

Earlier, in Chapter 10 of the General Theory you read the following:

If the Treasury were to fill old bottles with banknotes, bury them at suitable depths in disused coalmines which are then filled up to the surface with town rubbish, and leave it to private enterprise on well-tried principles of laissez-faire to dig the notes up again (the right to do so being obtained, of course, by tendering for leases of the note-bearing territory), there need be no more unemployment and, with the help of the repercussions, the real income of the community, and its capital wealth also, would probably become a good deal greater than it actually is. It would, indeed, be more sensible to build houses and the like; but if there are political and practical difficulties in the way of this, the above would be better than nothing.

Again a similar theme. The government can stimulate demand in a number of ways when private spending collapses. But they should choose ways that will yield more “sensible” products such as housing. He notes too that politics might intervene in doing what is best. When that happens the sub-optimal but effective outcome would be suitable.

So the answer is false. As long as the road builder is paying on-going wages to construct, tear up and construct the road again then this will be beneficial for aggregate demand (spending) which will ensure the national income flows associated with the project flow each year.

The workers employed will spend a proportion of their weekly incomes on other goods and services which, in turn, provides wages to workers providing those outputs. They spend a proportion of this income and the “induced consumption” (induced from the initial spending on the road) multiplies throughout the economy.

This is the idea behind the expenditure multiplier.

The economy may not get much useful output from such a policy but aggregate demand would be stronger and employment higher as a consequence.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you:

Question 2:

A ‘balanced budget’ rule adopted by a national government eliminates the swings in the fiscal balance that arise from the automatic stabilisers.

The answer is False.

The final fiscal outcome is the difference between total federal revenue and total federal outlays. So if total revenue is greater than outlays, the fiscal balance is in surplus and vice versa. It is a simple matter of accounting with no theory involved. However, the fiscal balance is used by all and sundry to indicate the fiscal stance of the government.

So if the fiscal balance is in surplus it is often concluded that the fiscal impact of government is contractionary (withdrawing net spending) and if the fiscal balance is in deficit we say the fiscal impact expansionary (adding net spending).

Further, a rising deficit (falling surplus) is often considered to be reflecting an expansionary policy stance and vice versa. What we know is that a rising deficit may, in fact, indicate a contractionary fiscal stance – which, in turn, creates such income losses that the automatic stabilisers start driving the fiscal balance back towards (or into) deficit.

So the complication is that we cannot conclude that changes in the fiscal impact reflect discretionary policy changes. The reason for this uncertainty clearly relates to the operation of the automatic stabilisers.

To see this, the most simple model of the fiscal balance we might think of can be written as:

Budget Balance = Revenue – Spending = (Tax Revenue + Other Revenue) – (Welfare Payments + Other Spending)

We know that Tax Revenue and Welfare Payments move inversely with respect to each other, with the latter rising when GDP growth falls and the former rises with GDP growth. These components of the fiscal balance are the so-called automatic stabilisers.

In other words, without any discretionary policy changes, the fiscal balance will vary over the course of the business cycle. When the economy is weak – tax revenue falls and welfare payments rise and so the fiscal balance moves towards deficit (or an increasing deficit). When the economy is stronger – tax revenue rises and welfare payments fall and the fiscal balance becomes increasingly positive. Automatic stabilisers attenuate the amplitude in the business cycle by expanding the fiscal balance in a recession and contracting it in a boom.

So just because the fiscal balance goes into deficit doesn’t allow us to conclude that the Government has suddenly become of an expansionary mind. In other words, the presence of automatic stabilisers make it hard to discern whether the fiscal policy stance (chosen by the government) is contractionary or expansionary at any particular point in time.

The first point to always be clear about then is that the fiscal balance is not determined by the government. Its discretionary policy stance certainly is an influence but the final outcome will reflect non-government spending decisions. In other words, the concept of a fiscal rule – where the government can set a desired balance (in the case of the question – zero) and achieve that at all times is fraught.

It is likely that in attempting to achieve a ‘balanced budget’, the government will set its discretionary policy settings counter to the best interests of the economy – either too contractionary or too expansionary.

If there was a ‘balanced budget’ fiscal rule and private spending fell dramatically then the automatic stabilisers would push the fiscal balance into the direction of deficit. The final outcome would depend on net exports and whether the private sector was saving overall or not. Assume, that net exports were in deficit (typical case) and private saving overall was positive. Then private spending declines.

In this case, the actual fiscal outcome would be a deficit equal to the sum of the other two balances.

Then in attempting to apply the fiscal rule, the discretionary component of the fiscal balance would have to contract. This contraction would further reduce aggregate demand and the automatic stabilisers (loss of tax revenue and increased welfare payments) would be working against the discretionary policy choice.

In that case, the application of the fiscal rule would be undermining production and employment and probably not succeeding in getting the fiscal balance into balance.

But every time a discretionary policy change was made the impact on aggregate demand and hence production would then trigger the automatic stabilisers via the income changes to work in the opposite direction to the discretionary policy shift.

You might like to read these blogs for further information:

Further, a rising deficit (falling surplus) is often considered to be reflecting an expansionary policy stance and vice versa. What we know is that a rising deficit may, in fact, indicate a contractionary fiscal stance – which, in turn, creates such income losses that the automatic stabilisers start driving the fiscal balance back towards (or into) deficit.

So the complication is that we cannot conclude that changes in the fiscal impact reflect discretionary policy changes. The reason for this uncertainty clearly relates to the operation of the automatic stabilisers.

To see this, the most simple model of the fiscal balance we might think of can be written as:

Budget Balance = Revenue – Spending = (Tax Revenue + Other Revenue) – (Welfare Payments + Other Spending)

We know that Tax Revenue and Welfare Payments move inversely with respect to each other, with the latter rising when GDP growth falls and the former rises with GDP growth. These components of the fiscal balance are the so-called automatic stabilisers.

In other words, without any discretionary policy changes, the fiscal balance will vary over the course of the business cycle. When the economy is weak – tax revenue falls and welfare payments rise and so the fiscal balance moves towards deficit (or an increasing deficit). When the economy is stronger – tax revenue rises and welfare payments fall and the fiscal balance becomes increasingly positive. Automatic stabilisers attenuate the amplitude in the business cycle by expanding the fiscal balance in a recession and contracting it in a boom.

So just because the fiscal balance goes into deficit doesn’t allow us to conclude that the Government has suddenly become of an expansionary mind. In other words, the presence of automatic stabilisers make it hard to discern whether the fiscal policy stance (chosen by the government) is contractionary or expansionary at any particular point in time.

The first point to always be clear about then is that the fiscal balance is not determined by the government. Its discretionary policy stance certainly is an influence but the final outcome will reflect non-government spending decisions. In other words, the concept of a fiscal rule – where the government can set a desired balance (in the case of the question – zero) and achieve that at all times is fraught.

It is likely that in attempting to achieve a ‘balanced budget’, the government will set its discretionary policy settings counter to the best interests of the economy – either too contractionary or too expansionary.

If there was a ‘balanced budget’ fiscal rule and private spending fell dramatically then the automatic stabilisers would push the fiscal balance into the direction of deficit. The final outcome would depend on net exports and whether the private sector was saving overall or not. Assume, that net exports were in deficit (typical case) and private saving overall was positive. Then private spending declines.

In this case, the actual fiscal outcome would be a deficit equal to the sum of the other two balances.

Then in attempting to apply the fiscal rule, the discretionary component of the fiscal balance would have to contract. This contraction would further reduce aggregate demand and the automatic stabilisers (loss of tax revenue and increased welfare payments) would be working against the discretionary policy choice.

In that case, the application of the fiscal rule would be undermining production and employment and probably not succeeding in getting the fiscal balance into balance.

But every time a discretionary policy change was made the impact on aggregate demand and hence production would then trigger the automatic stabilisers via the income changes to work in the opposite direction to the discretionary policy shift.

You might like to read these blogs for further information:

Question 3:

The private domestic sector will save overall even if the government’s fiscal balance is in surplus as long as net exports are positive.

The answer is False.

Focus on the “will” part of the question.

This is a question about the sectoral balances – the government fiscal balance, the external balance and the private domestic balance – that have to always add to zero because they are derived as an accounting identity from the national accounts. The balances reflect the underlying economic behaviour in each sector which is interdependent – given this is a macroeconomic system we are considering.

To refresh your memory the balances are derived as follows. The basic income-expenditure model in macroeconomics can be viewed in (at least) two ways: (a) from the perspective of the sources of spending; and (b) from the perspective of the uses of the income produced. Bringing these two perspectives (of the same thing) together generates the sectoral balances.

From the sources perspective we write:

GDP = C + I + G + (X – M)

which says that total national income (GDP) is the sum of total final consumption spending (C), total private investment (I), total government spending (G) and net exports (X – M).

From the uses perspective, national income (GDP) can be used for:

GDP = C + S + T

which says that GDP (income) ultimately comes back to households who consume (C), save (S) or pay taxes (T) with it once all the distributions are made.

Equating these two perspectives we get:

C + S + T = GDP = C + I + G + (X – M)

So after simplification (but obeying the equation) we get the sectoral balances view of the national accounts.

(I – S) + (G – T) + (X – M) = 0

That is the three balances have to sum to zero. The sectoral balances derived are:

- The private domestic balance (I – S) – positive if in deficit, negative if in surplus.

- The Fiscal Deficit (G – T) – negative if in surplus, positive if in deficit.

- The Current Account balance (X – M) – positive if in surplus, negative if in deficit.

These balances are usually expressed as a per cent of GDP but that doesn’t alter the accounting rules that they sum to zero, it just means the balance to GDP ratios sum to zero.

So what economic behaviour might lead to the outcome specified in the question?

If the nation is running an external surplus it means that the contribution to aggregate demand from the external sector is positive – that is adding to spending on domestically produced goods and services.

So if the fiscal outcome was in balance – neither adding or subtracting from aggregate demand, the external surplus would provide sufficient demand for the private domestic sector to save overall equivalent to 1 per cent of GDP.

Assume, now that the private domestic sector (households and firms) desires to save overall more than 1 per cent of GDP. Consistent with this aspiration, households may cut back on consumption spending and save more out of disposable income. The immediate impact is that aggregate demand will fall and inventories will start to increase beyond the desired level of the firms.

The firms will soon react to the increased inventory holding costs and will start to cut back production. How quickly this happens depends on a number of factors including the pace and magnitude of the initial demand contraction. But if the households persist in trying to save more and consumption continues to lag, then soon enough the economy starts to contract – output, employment and income all fall.

The initial contraction in consumption multiplies through the expenditure system as workers who are laid off also lose income and their spending declines. This leads to further contractions.

The declining income leads to a number of consequences. Net exports improve as imports fall (less income) but the question clearly assumes that the external sector remains in deficit. Total saving actually starts to decline as income falls as does induced consumption.

So the initial discretionary decline in consumption is supplemented by the induced consumption falls driven by the multiplier process.

The decline in income then stifles firms’ investment plans – they become pessimistic of the chances of realising the output derived from augmented capacity and so aggregate demand plunges further. Both these effects push the private domestic balance further towards and eventually into surplus.

With the economy in decline, tax revenue falls and welfare payments rise which would in this instance push the public fiscal balance into deficit via the automatic stabilisers if there were no discretionary policy changes made by government.

If the private sector persists in trying to increase its overall saving then the contracting income will clearly push the fiscal balance into a larger deficit.

So if there is an external surplus and the private domestic sector saves overall (a surplus) then the fiscal surplus has to be lower than the external surplus.

If the government tried to run a surplus greater than the external surplus then then the net drain on aggregate demand would reduce national income and saving for given investment levels and drive the private domestic sector into deficit.

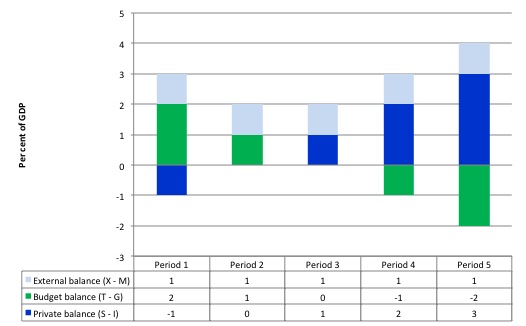

The following graph and related data table shows you how a fiscal surplus equivalent to the external surplus will not permit the private domestic sector to save overall.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you:

This Post Has 0 Comments