I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Recessions can always be avoided and should be

Recessions are very costly events. The income losses come quickly and sustain for several periods after the worst has occurred. Unemployment rises sharply and if government doesn’t take appropriate action (job creation), it takes a very long time to return to previous levels. The losses of income are huge and are lost forever. The related pathologies such as increased rates of family breakdown, increased crime rates, increased alcohol and substance abuse, increased suicide rates, increased incidence of mental and physical problems, the lost opportunities for skill development and work experience among the young, make the costs of enduring recession very high. These costs dwarf any of the estimated costs of so-called structural rigidities (micro imbalances) that have been produced by researchers over the years. Mass unemployment is the single greatest source of income loss. It is amazing therefore that policy makers do not prioritise the avoidance of recession yet expend vast energy talking about structural reforms etc. The fact is that recessions can always be avoided and should be. Governments can always adjust fiscal policy settings to ensure there is sufficient total spending in the economy to avoid recession, irrespective of what the private sector spending patterns are.

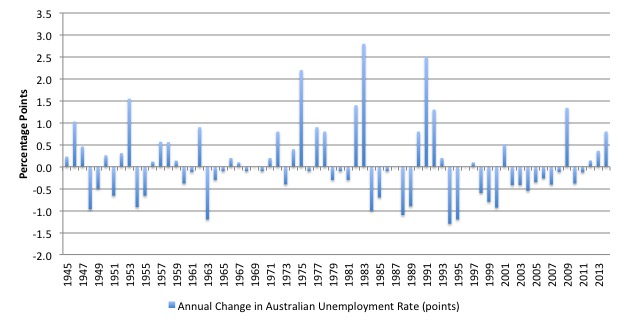

The following graph shows the annual change in the Australian unemployment rate from 1945 to 2014. A positive bar indicates a rise in unemployment rates and a negative bar a drop.

You can see how the pattern has changed over the period, which can be marked by two quite distinct policy regimes.

This year marks the 70th anniversary of the presentation of the – White Paper on Full Employment – to the Australian Parliament, which marked a defining event in policy history.

As an aside, my research centre – Centre of Full Employment and Equity (known as CofFEE) – will be holding a one-day workshop in either Sydney or Melbourne to mark the anniversay (Saturday, May 30, 2015). More details as we plan the event).

Prior to 1975, the Federal government was committed to maintaining true full employment and ran deficits most of the time to ensure there was sufficient aggregate spending to absorb the growing workforce.

After 1975, the Federal government progressively abandoned that commitment as the neo-liberal policy dominance took hold. The 1975-76 Fiscal Statement was the first of the era to demonise deficits and to enunciate an ‘inflation-first’ strategy. The Government knowingly allowed unemployment to rise as part of the swing to the right.

Please read my blog – Tracing the origins of the fetish against deficits in Australia – for more discussion on this point.

The pattern changed after 1975. The rises in unemployment associated with downturns were larger and the recovery periods much longer. By the 1990s, the Government was allowing unemployment to rise for four successive years and for the next 15 years, only 2 of them saw modest declines in the high unemployment rate.

This was the neo-liberal period’s legacy as unemployment became a policy tool (to suppress wage demands and redistribute national income to profits) rather than a major policy target, which it had been in the prior period after World War II.

The News Limited (Murdoch) press published an article on November 14, 2014 – Economist expects recession in 2015 – which reported on a bank economist’s prediction that a recession for Australia this year.

The prediction, in itself, is not startling. If policy settings do not change (that is, unless they become more expansionary) and the Federal government goes through with its ill considered plan to impose even more fiscal austerity, then Australia will certainly go close to negative real GDP growth in the middle two quarters of the year.

Growth slowed considerably in the September-quarter 2014 and last month the unemployment rate rose sharply (0.3 points) to 6.4 per cent, confirming the trend to negative employment growth.

So the economy is clearly heading down.

The startling aspect of the journalism was that it didn’t question the economist’s claim that:

AUSTRALIA is headed for recession and nothing can be done to stop it … “It’s too late, the wheels are in motion” …

He also claimed that the recession will “create a sense of urgency that could lead to simplification of taxes and regulation”.

First, no recession is inevitable. A responsible, currency-issuing government always has the financial capacity to bridge any spending gap brought about by a reduction in private investment.

In Australia’s case, the massive investment boom that was associated with the mining sector has now ended and with austerity the principle policy mindset driving unemployment up, the non-mining firms are reluctant to invest much.

Also compounding the malaise, is the fact that households are acting in a wary manner with respect to consumption spending, in part, because they are so indebted from the pre-GFC credit binge, and also because the fear of unemployment is present.

But the Federal government could clearly expand its fiscal deficit with appropriate targetted spending measures and job creation programs, which would quickly reverse the private sector stagnation.

That is what the Government always did in the pre- neo-liberal period. It made sure it smoothed out non-government spending cycles to minimise the impact on unemployment and income generation.

Needless to say, real GDP growth rates were higher on average in this period, recessions fewer and shorter, and unemployment averaged 2.1 per cent. Since 1975, unemployment has averaged 6.9 per cent. The differences are not related to regulations or tax structures but to the willingness of the Government to take responsibility for job creation when private sector jobs growth lagged.

Second, the solution is not to give tax breaks to corporations etc or to further deregulate. More tighter regulation is required in the financial sector (certainly in banking and financial planning).

The corporate sector wants massive labour market deregulation – wage cuts, overtime rates cut, job protections abandoned, occupational and health standards reduced, and the rest of it. That will only cut into consumer confidence further.

Investment is driven by firms hoping to sell the expanded output that the extra productive infrastructure makes possible. Consumption spending and government spending drives those sales. Firms will not take on extra staff if they cannot sell the output no matter how cheap it becomes.

For a wealthy nation such as Australia, the wage cutting route and the make-jobs-more-precarious route are not the way to general prosperity. It is not even likely to make many firms more profitable.

The article thus reflected the latest narrative that the ‘market’ determines outcomes and governments can do nothing to stop the trends, other than to deregulate and introduce other pro-business policy changes.

The exact opposite is the truth. The government can always dominate the market outcomes and shape the destiny of the economy to advance socially-desirable outcomes if it has the will.

The big difference between the two periods shown in the introductory graph is that the will of the government changed as the neo-liberal ideology began to dominate.

All the talk about structural rigidities, globalisation, excessive trade union influence, poorly designed income support systems, etc etc are just smokescreens to divert attention from the ideological distaste among neo-liberals for active government involvement which treats business as just one part of the economy rather than the economy.

And, further, these smokescreens are designed to disabuse us of the notion that the economy is just one part of and a servant of society and to promote the alternative neo-liberal notion that we are all just a bunch of competing, maximising individual and if left alone to pursue our own self-interests will deliver the best for everyone and everything. If anyone is left behind then they haven’t tried hard enough and if we stop to help them we will only entrench their inertness.

On Tuesday, the Fairfax press published an article that topped the one discussed above (February 17, 2015) – Australia needs a recession to ‘concentrate’ political minds.

Once again the national media journalist in Australia (and it is the same all over) thought that his role was to be a mouthpiece or spokesperson for some investment banker who wanted his twisted version of economics to be disseminated in the national press.

Presumably, there was a commercial motive for the visit to Australia by the banker from Edinburgh who gave us a lecture about how:

Australia might need a recession to focus political minds on the growing imbalances in the economy

The journalist might have asked at the outset what the commercial interests the Edinburgh-based global asset manager Standard Life Investments, which the chief economist was representing, were in Australia.

He might have enquired in some depth what exposure the investment bank had to Australian economic outcomes and, in particular, certain sectors that might benefit from the policy changes he was claiming to be necessary.

Silence. Not a single hint from the journalist.

The article was presented as if this economist had insights which were important for us to learn about.

The article said that:

… it could take a 1980s-style crisis to force politicians to tackle the country’s shrinking income base while restructuring expenditure. A global downturn, coupled with policy missteps and a febrile industrial relations environment, drove inflation well into double digits, and unemployment above 10 per cent, in the early 1980s. The deep, enduring recession led to many of the reforms that made Australia a free-trading, low-tariff, globalised economy.

What followed those recessions was an increasingly neo-liberal focus which abandoned full employment as an objective, created the conditions for increased casualisation of the workforce, more precarious jobs, sluggish real wages growth, a massive redistribution of national income to profits, increased income inequality, sluggish growth, entrenched high unemployment, and a massive buildup of household debt.

Further, our cities have become difficult due to the failure to invest sufficiently in public transport infrastructure, public hospitals and schools are strained and breaking down, and there is no coherent strategy for addressing climate change and environmental degradation.

Some progress! Australia has gone backwards in many important ways in the last three decades.

According to the article, the investment banker also subscribes “to the principle of a balanced federal budget”. Did the journalist ask him to explain the basis for that subscription?

Silence.

At present, with growth slowing and unemployment rising the fiscal deficit needs to be significantly larger than it is. It is highly unlikely given the long-period of external sector deficits and the current cautious return to saving by households that a fiscal surplus will ever be appropriate in the foreseeable future.

That is the conversation the nation has to have but no journalist will take it up. They all mindlessly buy into the we need to get back into fiscal surplus. Some become manic on that question (News Limited!), while others are prepared to run with the claim that there is no current urgency but it has to occur in the near future.

The investment banker was in the latter camp and said that “The whole obsession with quickly getting back to a surplus is really counter-productive.” We can agree on that.

But then, so as not to linger on the reasonable, he was quoted as saying that:

But structural impediments to growth have to be addressed by government policy – and it’s just not occurring.”

Growth slowed relatively quickly in Australia in the quarters after the fiscal stimulus was retrenched in 2012. It slowed further as private investment growth fell as the mining boom ended with the decline in the terms of trade (commodity prices – iron ore, coal etc).

Conversely, in 2009, real economic growth picked up very quickly when the Australian government introduced is rather large and quick fiscal stimulus. Australia avoided an official recession while most other nations entered the great recession.

No major structural changes, regulations, labour market rules, income support measures, tax structures, have changed over both periods.

The changes in growth rates are all down to aggregate spending and they have been dominated in the last six years by the fiscal swings and private investment (in response to terms of trade which are externally set).

Tax changes that have occurred have been favourable to business (mining and carbon tax abandoned). Growth has slowed further since those taxes were withdrawn by the Federal government.

If the government placed a few billion dollars of orders for public infrastructure and introduced a Job Guarantee (or any large-scale job creation initiative) then growth would rebound within a quarter – with zero structural change occurring.

That doesn’t mean that there needs to be structural changes to policies.

1. Banks need to be more tightly regulated.

2. Coal companies need to be put on notice that they will be closed down by law within 20 years.

3. Financial market regulations have to be introduced banning any speculative transaction that cannot be shown to advance the real interests of the economy.

4. Companies that pollute or otherwise degrade the environment have to pay fines and/or be closed down.

5. Wage setting institutions need to be empowered to ensure that real wages grow in line with national productivity growth to stop national income being redistributed to profits.

6. Lots more things here relating to inequality etc.

But none of these changes preclude the immediate growth stimulus that a fiscal policy intervention can achieve – any time the government has the will.

Finally, if a major recession was the stimulus for policy makers to act constructively and enhance the well-being of the people to whom they are accountable and responsible, how does the investment banker explain the Eurozone?

Conclusion

A passive press is a danger to democracy. Allowing these investment bankers to advance their commercial interests with little scrutiny and perpetuate myths about the effectiveness of fiscal policy interventions is a common practice among the fourth estate now.

There is never a need for a recession. They damage peoples’ lives – in some cases irretrievably. Suicide rates go up. Families break down. Mental and physical health falters. Crime rates rise. Poverty rises. Generations are denied work experience and on-the-job training and more.

As Arthur Okun wrote – the unemployment associated with recessions is “just the tip of the iceberg”.

Government fiscal intervention can always prevent a recession from occurring. It may not stop the fluctuations in private spending which would lead to a recession unchecked. But it can smooth out the aggregate spending variations that the private spending changes promote.

It is irresponsible to report that there is “nothing that can be done” to stop a recession.

Australian government considering dropping the 5-yearly population census

There was a Fairfax report from Peter Martin today (February 19, 2015) – Abbott government considers axing the Australian census to save money – that indicated the Australian government wants to drop the 5-yearly population census as a fiscal austerity measure.

You might also read this Fairfax article (February 19, 2015) – Census is good value and fundamental to our democracy.

I will write more about this issue once the facts become clearer.

But it is lunacy to abandon this data gathering exercise. The $440 million that will allegedly be saved is nothing. There is no financial crisis facing the Australian government. It has all the cash it needs and spending this amount will certainly not endanger any inflation barrier.

The Census is a magnificient dataset that researchers, policy makers, urban and social planners, etc use as an evidence base.

Personally, many of my published works in regional science have relied on the high quality data that the 5-yearly Census provides.

As Peter Martin writes:

The census offers a snapshot of where Australians come from, where they live, what type of families they have and how they work.

The small area and finely spatial-grained data that the Census provides, especially in regional areas, is irreplacable.

One of our leading demographers was quoted as saying:

It does what sample surveys cannot … It can track what is happening to comparatively small groups of people, such those born in particular countries. That can’t be picked up by smaller surveys … There is simply no other way of knowing how many people are in each town or suburb. Planners would be working without guidance. Over time it would be harder to know the size of the Australian population.

By way of juxtaposition, Matt Wade reported (second linked article) that the embarassing G20 meetings last year, which Australia hosted required Federal government outlays of $500 million.

Further, another Fairfax report today (February 19, 2015) – Abbott government’s metadata plan tipped to cost $300m – reports that the conservative government’s paranoid plan to force all telecommunication and Internet companies to keep massive databases of their customers’ metadata would cost $300 million.

This plan has massive flaws and will do nothing to reduce the risk of terrorist attacks.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2015 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Dear Bill

A dentist can only do something about your toothache after you already got one. Similarly, a government can only cure a recession after it already has started. No government has the prescience to know in advance when there will be a decline in private aggregate demand. It is therefore not quite accurate to say that governments can avoid recessions. It would be more accurate to say that they can make sure that we don’t have to stay in a recession very long once we have slid into one, just as a dentist can help us to get rid of a toothache quickly.

Regards. James

James,

I’ve never had a toothache. That’s because my dentist can spot signs of trouble in advance and fix any problem before it gets too serious.

Economists, at least the ones who study real economies rather that the pretend economies of mathematical models, can spot signs of trouble well in advance too. There’s no need for anything for anyone to suffer real economic pain in the developed economies. What’s happened in the EZ in the last few years is just crazy beyond belief.

“Mass unemployment is the single greatest source of income loss.”

Nope – mass unemployment is a consequence of income loss.

The last time I checked we lived in a age of capital.

“The related pathologies such as increased rates of family breakdown, increased crime rates, increased alcohol and substance abuse, increased suicide rates, increased incidence of mental and physical problems, the lost opportunities for skill development and work experience among the young, make the costs of enduring recession very high.”

I picked up this meme on another MMt site where they stated that euro growth was a fantastic thing in Ireland.

I am afraid to disappoint yee guys but I lived through it.

It was one of the greatest sociological disasters ever to hit the island.

The two spurts of growth in the 60s and 70s and again in the 90s and 00s turned the place into a nightmare.

Essentially these growth phases replaced a albeit extremely flawed victorian Christianity with the crass dogma of liberal materialism with predictable catastrophic consequences.

James, Australia’s actions in 2008 disprove your claim that a government can only cure a recession after it already has started.

The Dork of Cork –

Mass unemployment can be both the single greatest cause AND a consequence of income loss. Why do you try to deny the existence of feedback?

Alcohol consumption peaked in Ireland in 2001, the year before physical euro introduction.

It is down massively since then (25 % per capita I think) and also drinking is no longer a social thingy – its done at home to blot out the light.

Violent urban street crime is certainly down although robberies are up.

Raids on isolated farmsteads and older people is up as a result of police activity being concentrated on tax collection and corporate enforcement.

Serious drugs was introduced in the 1970s boom time as the orange banks scaled up their drug operations in Dublin and elsewhere.

The evidence is pretty conclusive , capitalistic type growth is bad news.

@Aidan

Banks produce credit and unemployment goes down

Banks call in their loans ( subtract money) and unemployment goes up.

What more evidence do you need ?

I am a recent convert to social credit.

I look on employment as a means to access purchasing power rather then do something useful for the most part.

Bill is mixing up cause and effect.

I guess it takes some time to recognise the nature of current religious doctrine but it seems pretty clear to me.

In Ireland one church was simply replaced by another.

@ The Dork of Cork

Credit is not the same as income.

Where mass unemployment is a consequence of credit loss, unemployment is the source of income loss, but the mass unemployment isn’t a consequence of income loss (unless the credit loss is itself the consequence of income loss, which is certainly a possibility but can not reasonably be assumed).

Maybe our oligarchy would like to see a recession. After all,it has been a neocon modus operandi for some time to never waste a crisis in order to further their own agenda.

Somewhat on topic I hope, here is Glen Stevens:

Mr Stevens : “With the scenario I have given I will be accused perhaps of being too gloomy, and I do not want to do that. But why do you want a surplus? Why do you want low debt? Well, one of the big reasons you want it is that on a rainy day, when something big goes wrong and the government wants to expand fiscal policy to help the economy, like we did in 2009, you want the scope to do that. We had scope then, and we probably would have scope now if something really bad happened. But you do not want to be in a position where that scope has become limited because the financial markets accord you less discretion than they would today.”

Correct me if I am wrong, but this man is implying that govt. spending is entirely dependent on market borrowing. Isn’t that just rubbish from an MMT viewpoint?

Today I was discussing fiscal stimulus projects that might address unemployment. One suggestion was a big stimulus into residential housing ie public housing, but a colleague pointed out a likely skills shortage. After Bailleau was elected 5 years ago, our TAFE sector (in Victoria) was absolutely gutted, so now there is quite a shortage in many trades. (I think similar happened in NSW TAFEs). If this is right, then part of any such stimulus should go into trying to get young people skilled up more in the trades. I am a newcomer to this site and MMT generally and have not seen anything yet about this point so if anyone can suggest reading on it I would be grateful. I am certainly not suggesting that projects that did not require special skills or qualifications would not be worthwhile, but just that in the medium to long term most people prefer work that is a bit more demanding and interesting.

“In any manufacturing undertaking the payments made may be divided into two groups: Group A: Payments made to individuals as wages, salaries, and dividends; Group B: Payments made to other organizations for raw materials, bank charges and other external costs. The rate of distribution of purchasing power to individuals is represented by A, but since all payments go into prices, the rate of generation of prices cannot be less than A plus B. Since A will not purchase A plus B, a proportion of the product at least equivalent to B must be distributed by a form of purchasing power (national dividend ) which is not comprised in the description grouped under A.” (C.H. Douglas, “The Monopoly of Credit”)

The first criticism, which states that B payments are income, implicitly assumes the quantity theory of money. According to this theory, all money received by firms is income and can be used to purchase other goods and services. The theorem states that the quantity of transactions, multiplied by the quantity of money, equals total purchasing power. On the surface, this theory seems to make sense, but upon further investigation, it is not a reflection of reality. In reality, firms have costs that must be repaid. These costs can ultimately be traced back to bank debt because all money originates as debt. If a company receives $10 for its product, and assuming accumulated costs of $8.50 to acquire and sell this product, then only $1.50 is actually profit to the company, and potential income. The $8.50 must be used to cancel debts, or replace working capital. All of the $10 received by the company is not income. The fallacy was pointed out in “The Alberta Post-War Reconstruction Committee Report”.

“The fallacy in the theory lies in the incorrect assumption that money “circulates”, whereas it is issued against production, and withdrawn as purchasing power as the goods are bought for consumption. ” ( “The Alberta Post-War Reconstruction Committee Report of the Subcommittee on Finance”)

Dork – money circulates in a medieval market town economy but not in a industrial economy

“Categorically, there are at least the following five causes of a deficiency of purchasing power as compared with collective prices of goods for sale: –

1. Money profits collected from the public (interest is profit on an intangible)

2. Savings, i.e., mere abstentation from buying

3. Investment of savings in new works, which create a new cost without fresh purchasing power

4. Difference in circuit velocity between cost liquidation and price creation which results in charges being carried over into prices from a previous cost accountancy cycle. Practically all plant charges are of this nature, and all payments for material brought in frm a previous wage cycle are of the same nature.

5. Deflation, i.e. sale of securities by banks and recall of loans” (C.H. Douglas, “The New and The Old Economics”)

The Social credit maxim

The true costs of production is (human level) consumption.

Not the sort of capital goods consumption you typically see in the post war / post agrarian Irish economy of traffic jams and human misery.

Dear Bill/Anyone who might know:

When was the last time the Australian government lifted its voluntary constraint whereby it issued bonds at a 1:1 ratio with spending? (i vaguely recall this might have been the sydney olympics in 2000?)

@James Schipper

Recession prevention is the weather forecasting of macro-economics. As far as i know the only groups that can give a decent long term forecast are (minsky aware groups) whom model the realistic stock flows of money, look at aggregate levels of private debt (sectorial balances), disposable income, employment numbers, financial speculation and real physical resources.

The list of factors i have just stated is almost mutially exclusive from the toolbox used by most of the people advising the government and writing articles in the mainstream media. I see a lot of rubbish about ‘currency ratings’ how to best reinforce what are essentially speculative market forces and panic about currency depreciation (imports/ecports).

Its pretty simple in Australia’s case for any sane political party. Start by augmenting the minimum wage, increase the public service, have a hand in some large scale employment projects to create infrastructure.

Looking at Australia by sectorial balances: In a normal cycle the ‘happy medium’ of government spending to taxation is probably avbout 3% defecit and in a downturn based on what needs to be done government may have to spend 10-15%. Basically whatever is needed to achieve policy goals but if your policy goal is to limit government spending (Hockey’s one goal) than watch everything stagnate then melt down. Not hard to forecast that 😉

Also, profits only represent a portion of the gap between income and prices. Douglas did not seek to eliminate profits, instead he wanted to compensate for the gap between income and prices which profits helped create. (Social credit blogspot)

“The essential point to notice, however, is not the profit, but that he cannot and will not produce unless his expenses on the average are not more than covered. These expenses may be of various descriptions, but they can all be resolved ultimately into labour charges of some sort (a fact which incidentally is responsible for the fallacy that labour, by which is meant the labour of the present population of the world, produces all wealth). Consider what this means. All past labour, represented by money charges, goes into cost and so into price. But a great part of the product of his labour -that part which represents consumption and depreciation – has become useless, and disappeared.” (C.H. Douglas, “The Control and Distribution of Production”)

If memory serves me right current depreciation in the Irish economy as presented on the national accounts is 25 to30 billion a year – this in a economy with. National income of 100 ~ billion a year.

This is obviously catastrophic as it is the true costs of the depreciation of capital goods previously used as a mechanism to access purchasing power.

We can again see the Irish economy gaining purchasing power by using this perverse means ( Car sales are up massively ) but at a enormous future cost of further depreciation costs down the line.

@Chris Coney

“””If this is right, then part of any such stimulus should go into trying to get young people skilled up more in the trades. I am a newcomer to this site and MMT generally and have not seen anything yet about this point so if anyone can suggest reading on it I would be grateful.”””

One would think any competent employment ‘minister’ should be able to ratle off a few figures about number of students expected to finish secondary education and likely number that will go into trades or university education system year-to-year. (and have a sensible policy for this) A qualification is a 3-4 year delay as a ‘human capacity constraints’ and a competent government should be able to plan for such physical limitations. (limitation is certainly not the governments fiscal position) Furthermore if said government was sane they’d be planning to expand the capacity of the workforce to fulfill such constraints.

Instead of this there is a shift to reduce the capacity to train trades people. (Yes TAFE is repeatedly gutted its a joke now as federal fiscal stance will affect state government spending on such things), import cheap labour from overseas all while simultaneously claiming there is a skills shortage whil’st watching youth unemployment continually rise.

Raising aggregate demand will drive the employment of a trades person once they have mastered their trade. At the moment it seems that there is neither willingness to acknowledge the issue is demand driven (myth of ‘supply side’ economics) hence there is no attempt to increase demand.

Skills shortage:

https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=22082

https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=16629

https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=42

Basic fall back position of a job guarantee ’employer of last resort’:

http://neweconomicperspectives.org/2012/03/mmp-blog-43-job-guarantee-basics-design-and-advantages.html

https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=1868

A example of how wildly variable Irish national accounts can be from year to year.

Table 7 Y2012 accounts published 2013

Y2008

Total personnel and gov expenditure : 124,532 million

Gross national saving : 19,898

Provision for depreciation : 16,179

Net national saving : 11,068

Jump forward to 2013 Accounts published in 2014

Y2008

Total personnel and gov expenditure : 125,486 million

Gross national saving : 34 ,39 3

Provision for depreciation : 23, 894

Net national savings : 10,499

In the 2009 period we can see the troika was brought in for a so called savings crisis rather the a balance of payments crisis.

Both 2012 and 2013 accounts state that net national savings was a mere 2,954m and 2,712 respectively.

Prevention is cheaper than repair. That’s been obvious to peasants since the beginning of human history.

It’s entirely academic until we zero in on practical steps that will prevent our aggregates from repeating this same mistake every 3 generations. Then we can go on to making & correcting more interesting mistakes.

Any suggestions about K-12 curriculum? Now THAT would start to make a difference.

Totaram: no you’re not wrong and yes it’s rubbish.

Sam: well, read more Bill Mitchell.

Pertaining to your opening question, training people to skills or trades does not create jobs. So training youth only gives you trained, unemployed youth.

Dork,

Can you settle it down a bit please? SEVENTEEN of these comments are yours, and that’s probably ten too many. Lots of people have questions, answers, and input, we don’t all want to read pages and pages of your rants. You can make your own blog for thinking out loud.

nicky9finger: Thank you. The question then arises: is the RBA Governor lying/dissembling or does he really not understand how things work? And if the answer to the second part is yes, then I am astounded.

Sam: why would a govt. issue bonds equal to expenditure, when the amount equal to deficit or even less is possible? This means the govt. is running up an unnecessary interest bill. In any case, if this is voluntary as you say, who decided that this should be done?

Here is more from the RBA Governor:

Mr Stevens : If you want to compare debt-servicing costs, you can multiply the debt by the interest rate across countries and get the number. Japan are borrowing at a third of our rate, but they have a lot more than three times the amount of debt we have. So I think they still have a much more difficult position than us, and it is amazing that the capital market will lend to them at that rate. Actually, the reason that is happening, in part at least, is that their central bank is the one buying the debt-not something we are proposing to do here. So I think it is correct to say that you have to think about the cost of debt service. This is not an unmanageable problem for our country at this point in time.

So, putting together Sam’s statement of 1:1 issuance of bonds for expenditure and the above statement, I hypothesize that Glen Stevens thinks that all expenditure is funded by the financial markets because they are the ones that buy the bonds. The RBA buys and sells bonds only to keep the interest rate pegged. He is aware that the RBA can buy those bonds directly from the treasury, but only when the fin. institutions don’t buy them any more, and he feels that would be terrible (for some odd reason). He doesn’t see that the RBA buying most of the treasury bonds is equivalent to the govt. running fiscal deficits without issuing bonds.

Does that make sense?

I am unable to find out exactly who, what or why triggers the issuing of treasury bonds. I have seen a statement from the head of the AOFM stating categorically that bonds are not issued to cover the fiscal deficit, although I cannot find it now. So what is the real situation?

Yet the mainstream always fret about inflation despite Zimbabwe and Germany in the 30s, their two examples, shown to be BS. Never mention debts in a foreign currency or the collapse in farm productivity in Zimbabwe.

South American countries with steady inflation show them to be wrong.