I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Fiscal austerity drives continuing pessimism as oil prices fall

The UK Guardian article (January 20, 2015) – Davos 2015: sliding oil price makes chief executives less upbeat than last year – reported that the top-end-of-town are in “a less bullish mood than a year ago” and that “the boost from lower oil prices is being outweighed by a host of negative factors”. The increasing pessimism is being reflected in the growth downgrades by the IMF in its most recent forecasts. A significant proportion of the financial commentators and business interests are now putting their hopes on the ECB to save the world with quantitative easing (QE). That, in itself, is a testament to how lacking in comprehension the majority of people are about monetary economics. QE will not save the Eurozone. But I was interested in this pessimism in the context of falling oil prices given that with costs falling significantly for oil-using sectors (transport, plastics etc) and disposable income rising for consumers (less petrol costs), the falling oil prices should be a stimulating factor. I recall in the 1970s when the two OPEC oil price hikes were the cause of stagflation. So why should the opposite dynamic cause ‘stag-deflation’ (a word I just invented)? There is a common element – fiscal austerity – which explains both situations.

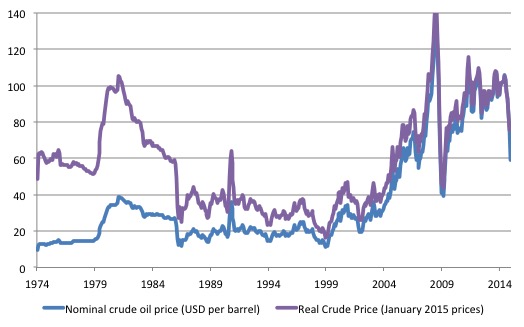

The following graph shows the history of monthly crude oil prices in US dollars per barrel from January 1974 to December 2014. The blue line is the actual (nominal) price and the purple line is the real equivalent where the nominal price has been adjusted by the US Consumer Price Index and expressed in terms of January 2015 prices.

Notable is the size of the real shock in the 1970s. Mostly nominal prices have moved in line with the general movement in prices.

The data is available from the – US Energy Information Administration.

As an explanation of what is going on at present, I think this article by Fairfax economics editor, Peter Martin (January 13, 2015) – Falling petrol price good news for consumers but why didn’t experts see it coming? – was interesting and informative.

Oil price shifts in the 1970s ended the Keynesian era

The OPEC oil price hikes in the 1970s provided the switch point that saw the conservative ideas regain ascendancy despite them being cast into disrepute during the 1930s by the work of Keynes and others.

The world economy and the currency markets were severely disrupted by the outbreak of hostilities in the Middle East in October 1973 (the 1973 Arab-Israeli War).

This was accompanied by the oil embargo imposed by the Organization of the Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries (OAPEC).

A few days later, on October 16, the Arab nations increased the price of oil by 17 per cent and indicated they would cut production by 25 per cent as part of a leveraged retaliation against the US President’s decision to provide arms to Israel.

The price of oil rose by around 3 times within eight months.

The economies of Europe and Japan, which were heavily dependent on oil as the primary energy source were severely impacted by the rising prices. The US economy was less affected owing to its lesser dependence on imported oil.

The result, the US dollar appreciated by 17 per cent in the six months to February 1974, basically taking it back to the December 1971 value at the time of the signing of the Smithsonian Agreement. Further, the European currencies suffered major depreciation, as did the yen.

On January 19, 1974, the French government decided to float and exit the ‘snake’ because it was facing a major strain on its foreign exchange reserves as a result of its dependence on imported oil.

The oil price rises soon fed into the general price level and accelerating inflation became widespread.

The inflation of the 1970s was not the same beast that the deficit terrorists were predicting over the last 6 or 7 years would strike as a result of the rising fiscal deficits.

Economists distinguish between cost-push and demand-pull inflation although the demarcation between the two “states” is not as clear as one might think.

In this blog – Modern monetary theory and inflation – Part 1 – I outlined the demand-side theory of inflation. Essentially, if nominal spending outstrips the capacity of the economy to meet that demand with higher real output, the economy will enter a demand-pull inflationary phase.

The excess demand ‘pulls’ prices up.

The reason the deficit terrorists were wrong is because they didn’t understand the difference between a price-adjusting and quantity-adjusting states.

When there is excess capacity (supply potential) rising nominal aggregate demand growth will typically impact on real output growth first as firms fight for market share and access idle labour resources and unused capacity without facing rising input costs.

Under these conditions, firms will be quantity-adjusters with respect to spending increases.

As the economy nears full capacity the mix between real output growth and price rises becomes more likely to be biased toward price rises (depending on bottlenecks in specific areas of productive activity). At full capacity, GDP can only grow via inflation (that is, nominal values increase only).

Under these conditions, firms will more likely be price-adjusters with respect to spending increases.

The rising costs ‘push’ prices up.

Cost-push inflation is an easy concept to understand and is generally explained in the context of ‘product markets’ (where goods a sold) where firms have price setting power. That is, the perfectly competitive model that pervades the mainstream economics textbooks where firms have no market power and take the price set in the market, is abandoned and instead firms set prices by applying some form of profit mark-up to costs.

Please read my blogs – Modern monetary theory and inflation – Part 2 – for more discussion on this point.

The OPEC cartel knew that the oil-dependent economies had little choice, at least in the short-run, but to pay the higher oil prices.

This represented a real cost shock to all the economies – that is, a new claim on real output. The reality is that some group or groups (workers, capital) had to take a real cut in living standards in the short-run to accommodate this new claim on real output.

At that time, neither labour or capital chose to concede and there were limited institutional mechanisms available to distribute the real losses fairly between all distributional claimants.

The resulting wage-price spiral came directly out of the distributional conflict that occurred. Another way of saying this is that there were too many nominal claims (specified in monetary terms) on the existing real output.

This explanation of inflation is variously referred to as the battle of the mark-ups’, the ‘conflict theory of inflation’ or the ‘incompatible claims’ theory of inflation.

The inflation dynamic is a ‘cost push’ because its initial source is a rise in costs that are then transmitted via mark-ups into price level acceleration especially if workers resist the real wage cuts that capital tries to impose on them – to force the real costs of the resource price rise onto labour.

Ultimately, the government can choose to ratify the inflation by not reducing the nominal pressure or it can break into the wage-price spiral by raising taxes and/or cutting its own spending to force a product and labour market discipline onto the ‘margin setters’.

The weaker demand forces firms to abandon their margin push and the weakening labour markets cause workers to re-assess their real wage resistance. That is ultimately what happened in the 1970s.

In the 1970s, the high inflation that followed the OPEC oil price hikes was accompanied by high unemployment as governments tried to suppress economic activity to control the inflation.

This era of stagflation (‘stag’ referring to the recession and rising unemployment and ‘flation’ to the price level acceleration) provoked a major shift in economic thinking.

The Keynesian macroeconomic orthodoxy, that dominated the post World War II period, was predicated on the view that the total spending in the economy determined the level of unemployment. Firms employed people if they had sales orders.

After the cessation of WW2 and with the mass unemployment of the Great Depression of the 1930s still firmly etched in the minds of policy makers and the population, governments generally committed to using fiscal and monetary policy to maintain states of full employment where everybody who wanted a job could find one. This led to an acceleration of prosperity across the advanced world.

Accompanying this approach was a view that inflation would only result if the spending outstripped the capacity of the firms to produce goods and services, leaving them no option but to increase prices.

Accordingly, high unemployment should be associated with low inflation and vice-versa. Stagflation thus presented a new situation.

Most economists understood that inflation could also emerge as a result of sudden cost pressures (for example, imported oil price rises) which then squeezed existing profit margins and the real value of the workers wages, and under certain circumstances, could trigger a struggle between labour and capital over who would bear this loss

Inflation would result if workers gained wage rises and firms responded by pushing up prices or vice versa. The correct policy response was to address the incompatible demands for more national income from labour and capital by seeking some sort of consensual approach to sharing the costs of the imported raw material price rise.

However, this understanding was lost on policy makers when responding to the OPEC oil price hikes and they sought to stifle the accelerating inflation by suppressing spending using policy measures we now refer to as fiscal austerity (public spending cuts and/or tax increases) and tight monetary policy (increasing interest rates).

The resulting stagflation created a perception that Keynesian policies had failed and bestowed a sense of legitimacy on the free market approach, which had claimed that inflation was the result of lax government policy. This view had been wholly discredited during the Great Depression by the work of John Maynard Keynes and others, but remained alive and well in the more conservative academic departments.

The long-standing dominance of Keynesian policy was thus abandoned by a large number of economists in the 1970s. The US economist Alan Blinder noted in 1987 that by:

… about 1980, it was hard to find an American macroeconomist under the age of 40 who professed to be a Keynesian. That was an astonishing turnabout in less than a decade, an intellectual revolution for sure.

The resurgence of the free market approach, which we now rather roughly refer to as neo-liberalism manifested initially as Monetarism, and Milton Friedman and his University of Chicago colleagues championed the entry of these ideas back into the mainstream policy debate.

The rise of Monetarism was not based on an empirical rejection of the Keynesian orthodoxy, but was according to Alan Blinder:

… instead a triumph of a priori theorising over empiricism, of intellectual aesthetics over observation and, in some measure, of conservative ideology over liberalism.

It represented a shift from those who consider that state intervention, regulation and spending is crucial for the achievement of a balanced and equitable economy, to those who eschew state involvement and believe, with religious passion, that a self-regulating free market can provide increasing wealth and opportunity for all.

The core Monetarist idea was that excessive growth in the money supply associated with excessive government spending and lax monetary discipline by the central banks (interest rates too low) caused inflation.

Further, price stability required the imposition of deflationary policies, which involved tighter credit policies and cutbacks in fiscal deficits.

The Monetarists introduced the concept of the natural rate of unemployment, to combat the view that the austerity would generate higher unemployment.

Put simply, they argued that a free market would deliver a unique unemployment rate that was associated with price stability and that government attempts to manipulate that rate using fiscal and/or monetary policy would only lead to accelerating inflation.

The prescription was for policy makers to concentrate on price stability and let unemployment settle at this ‘natural’ rate, ignoring popular concerns that it might be too high.

By this time, any Keynesian remedies proposed to reduce unemployment (such as, increasing the fiscal deficit) were met with derision from the bulk of the economics profession who had wholeheartedly embraced Monetarism.

Despite the predominance of Monetarist thought at the time, there was very little factual evidence presented to substantiate their policy approach.

In fact, it flew in the face of all reasonable logic. It was a triumph of free market ideology over the facts.

But with policy makers increasingly loathe to use discretionary fiscal and monetary policy to stimulate the economy, unemployment rose and persisted at high levels.

The battle against high unemployment was abandoned in order to keep inflation at low levels.

So it was clear why recession ensued and unemployment rose quickly – fiscal austerity was imposed which killed off spending growth and damaged sales. Firms responded by laying off workers.

Why should firms be pessimistic when oil prices are falling so sharply?

During the GFC, oil prices fell sharply as you can see from the graph at the outset of this blog. But the relief was short-lived and as fiscal stimulus led to the early stages of recovery, the prices rose again.

The more recent price cuts are not of the same ilk. The Saudis are clearly engaged in a strategic exercise to drive the higher cost oil explorers in North America and Russia broke and are prepared to accept lower margins in order to achieve that objective.

The falling prices are what economists would call a reverse supply-side (cost) shock – a favourable one. Consumers will have more disposable income and firms will have lower unit costs.

So why wouldn’t that invoke optimism?

The answer is obvious. Any beneficial impacts from the supply-side of the world economy are being offset by the demand-side contractions brought about by on-going fiscal austerity.

Even with deflation, firms will not hire and expand production if they do not expect the sales environment to be favourable in the immediate future.

Firms hire workers to produce goods and services for sale. They will not employ to produce unsold inventories no matter how cheap labour or other essential raw material inputs becomes.

The on-going mainstream obsession about fiscal surpluses and the operation of the fiscal rules in the Eurozone are clearly creating a negative future outlook about the state of expected demand.

So in the 1970s, we had stagnation with accelerating prices because of fiscal austerity (demand-side response) responding to a major supply-shock (oil price rise).

Now we are facing on-going stagnation with decelerating prices and even deflation (falling price levels) because of because of fiscal austerity (demand-side response) even though the global economy has enjoyed a major beneficial supply-shock (oil price fall).

Conclusion

There is no mystery as to what is going on at present. One might expect that a fiscal stimulus now would be more effective than before the oil price fall because firms might are facing cost reductions and consumers have more disposable income available as a result of the energy price falls.

But the dominant dynamic is not coming from the supply-side (the oil price cuts) but from the on-going suppression of spending as a result of the ill-considered imposition of fiscal austerity.

The deficit terrorists really have a lot to answer for.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2015 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Bill,

I’m not sure about your claim that in the 1970s, politicians didn’t understand that “The correct policy response was to address the incompatible demands for more national income from labor and capital by seeking some sort of consensual approach to sharing the costs of the imported raw material price rise.”

In the UK at least, HUGE EFFORTS were made to cobble together some sort of nationally agreed wages, prices and profits controls. E.g. there was Barbara Castle’s “In place of strife” legislation. (Castle was a senior Labour politician).

The real reason politicians “sought to stifle the accelerating inflation by suppressing spending using policy measures we now refer to as fiscal austerity” wasn’t because they didn’t see the merits of the above “controls”: it was because they couldn’t get trade unions and/or employers to agree to those controls.

However, I agree with your point that the real dummies in that period were the economists who jumped to the conclusion that the whole Keynsian stimulus idea was floored just because we had a temporary period of cost push inflation sparked off by oil price increases.

“it was because they couldn’t get trade unions and/or employers to agree to those controls.”

If you can’t get people to agree, then you have to enforce something. The problem with the Labour government is that they didn’t park a big enough stick in the corner of the room before dealing with people. Too much appeasement.

So the people elected somebody who was all big stick.

That remark Neil is very easy to make but covers a multitude of sins. If it was as straightforward as you suggest there really might not need to be something like “the market” to act as a final arbiter in an economy that has to compete on an internationally competitive basis.

I have heard from some commentators that oil price declines hurt collateral loan values and limit credit availability from banks.

Many banks have lent out heavily to capital intensive energy projects.Lower prices could lead to poorer performing bank balance sheets and consequently have an adverse affect on their capital ratios.

This in turn could lead to bank insolvency or at least limit lending into other sectors.In short, reducing bank led private sector investment.

This could be why their is such limited optimism about the oil price decline.Further shocks to the financial sector,having real affects on the rest of the private sector.

Gogs, the market is not a final arbiter. It rather functions analogously to crowdfunding for companies, or at least it did when its primary function was for companies to obtain funding. With the advent of complex derivatives and its ilk, which should be banned, its functionality now appears to be primarily that of a parasite that eats its host if left uncontrolled.

Dear Bill

The falling oil prices don’t increase global demand. Oil consumers have more money to spend, but oil producers have less. It is a change in the terms of trade. Oil importers are the winners and oil exporters are the losers. I don’t see how it can be a stimulus to the world economy. Firms that sell to oil consumers will have more demand, but firms that sell to oil producers will have less.

Regards. James

James, which oil consumers do you have in mind that have more money to spend? It isn’t in general the 99%. nOt according to Piketty’s data.

Dear Larry

In the summer, I was paying 130 Canadian cents for a liter of gasoline. Today, I’m paying 90. Suppose that I consume 1500 liters per year, then I now have 600 more dollars that I can spend on other things in a year. That’s what I meant.

Regards. James

This absolutely the best site on the internet.

Working in a area within a marginal distance of me home port this week.

In the past ( 6 months ago) the 3 guys in a ford transit may have decided to get a B & B rather then travel back and forth everyday….now its cheaper to waste fuel..

The area once had a rail route until 1960 ~

The lack of rail causes congestion and therefore fuel waste as people commuting to access purchasing power ( not working in the main) enter the city every week day morning.

Bill fails to see what really happened to the world economy in the 50s & 60s.

So as to access purchasing power ( get and maintain a job whether productive or not) one must burn through a epic amount of capital goods.

These machines ( typically cars ) require a epic amount of energy inputs.

Economies become vulnerable to oil rentiers or in the case of mature industrial economies exposed to 100s of industrial activity – depletion – see UK fossil fuels.

The first post war oil crisis – Suez , caused a crisis in the British banking conduit economy of Ireland .

car purchases were cut in half during that time.

Of course no such crisis would have happened if people had enough purchasing power so as to use the then closing rail system of Ireland.

Usury always expresses itself through waste eventually.

The best conservation measure is to slow down.

For example for the above workmen to remain near their workplace overnight.

This requires bottom up interest free debt.

Where people have enough tokens to buy local accomadation and food while real external inputs express their true costs.

There is no such thing as a free market at least in the case of crucial commodities. Any theory predicated on an a priori assumption of free markets in this sphere falls at the first hurdle. Saudi Arabia (probably at the orders of the US) has flooded the market with cheap oil. The drop in oil price, by design, achieves a number of goals for USA and Western capitalism. It damages Russia and Venezuela, two of the USA’s ideological, economic and geostrategic enemies. It undercuts renewable energy with cheap oil. It undercuts the development of electric cars. It even undercuts efforts to reduce fossil fuel use in the short to mid-term as oil consumption will likely rise again under a low price regime.

To sum up, the drop in the oil price comes at or about the same time as the struggle to control Ukraine, to sanction Russia and to prevent efforts to address CO2 emissions. All of this is very deliberately planned at the highest levels in the US oligarchy.

All really existing markets have arbitrarily set characteristics, rigged characteristics and any “freedom” (so-called) is limited freedom or “freedom within bounds”. The bounds are arbitrarily set (i.e. politically and legally set) and naturally set (by what is possible in the natural world).

In the modern political economy of RECD, or Really Existing Capitalism & Democracy, as opposed to some idealisation of the free market which does not and cannot ever exist in reality, the choice is not whether to have a rigged market or not. The choice is which kind of rigging to put in place and who you will allow to do that rigging. The choices in our system of RECD are very clear but the propagandised ill-educated population can’t see them. Either you let corporations and oligarchs (capitalism) rig the market or you let the people (democracy) rig the market. Here “rigging” means control. Divested of its moral assumptions (which lead to markets being called “rigged” or “free” depending on your point of view) rigging is really about control.

The question of “fundamental value” seems to me to arise in connection to markets however they are rigged (controlled). Markets appear to be poorly adapted to appraise the fundamental value of many things and many factors to humans. This is a difficult question to deal with because of the difficulty in (i) defining fundamental value at all and (ii) in quantifying fundamental value in a money system. The money system seems to exist to allow equations of unlike products as in 1 type y car = x metric tons of type z bananas (depending on point in time and place prices).

What is the fundamental value of oil? Given our current economy, the fundamental value of oil is illustrated by the fact that our economy would totally collapse without it. (This is assuming we have not yet made enough transition to other energy sources and industrial feedstock sources which assumption is currently valid.) In this sense the value of oil is infinite. An example with a person and food will help. What is the fundamental value of food to a person? Without food the person will die. Therefore if the person was starving, possessed infinite money and was offered food only at an infinite price, that person would pay an infinite amount. The fundamental theoretical value of food in this case is infinite. In like manner the fundamental value of oil to our current oil-dependent economy is effectively infinite (absolutely necessary).

At the same time oil and other fossil fuels demonstrate another characteristic. If we keep on with business as usual and burn them all we will seriously damage our climate and our economy to the point that civilization and even our species existence will likely collapse. In this sense, oil has another infinite value but it is actually a value of negative infinity. Oils (plus other fossil fuels) are so dangerous that using them all up will destroy civilization and all human life. What value do we put on that? Theoretically we would pay any money price to avoid that so the fundamental theoretical value of oil in this case is negative infinity.

How can a market system value-appraise a product which shows the short to mid-term characteristic of being theoretically infinitely valueable and the long term close-to-certain prospect (well above 95%) of being theoretically of infinite negative value? I suspect there probably is a way of solving this mathematically but it certainly cannot be solved by markets. The mathematical equations would be of a form, the graphed results of which, would approach the negative infinite limit in one direction and the positive infinite limit in the other. (The formula y=x^3 gives an idea of the general shape but is not the specific formula(s) required. I leave that to the mathematicians.)

By feeding in probabilities, paramaters and limits, the pricing profile could be calculated which allowed use of fossil fuels now, forced the transition rates to renewables at or close to the technical-scalability limits of transition, and avoided dangerous global warming. (Probably more than about 1.5 C warming is dangerous.) This equation would give the best estimate possible of the fundamental value of oil to us as a global civilization at each successive point in time. This illustrates that the value of oil should now be totally controlled, set and progressively raised by pure scientific-mathematic methods. That is, we should now totally rig the oil market in this manner. It would be the logical, scientific, moral and existentially survivable thing to do.

As the Stern Report indicated “Climate change is the greatest and widest-ranging market failure ever seen.” Markets cannot solve such problems. Markets are existentially obsolete in relation to the new survivability problems we now face globally. The only hope is to reduce scientific and political-economic illiteracy among the population and then implement via educated democratic demand, the scientific pricing of key commodities to ensure equity and indeed human survival.

I find some of Bill’s stuff very commendable – particularly his ideas regarding the importance of countries having their own freely floating currencies, and, in this scenario, the impossibility of their becoming insolvent. Many good policy options flow from this.

However, I am not sure Bill’s analysis (above) of the inflation resulting from the first oil price spike is that convincing.

Bill’s explanation of what causes inflation is similar to Friedman’s. When aggregate demand exceeds some ‘NAIRU’ level, both argue inflation takes off. Friedman also recognised that the effect of the oil price rise was a structural change in the world economy, shifting spending power to oil producers. However, Friedman argued ( I think convincingly) that this changed, temporarily, the NAIRU unemployment levels in countries. Labour and capital had to be redeployed to new activities as a result of this shift in spending power. Unemployment rose as a result of this transition and redeployment. However, policy makers had become used to very low levels of unemployment in the previous stable decades; they responded to the increased unemployment by cutting interest rates and over stimulating demand- hence the inflation of the 1970’s.

I think this orthodoxy is reasonably convincing.

Today’s problems are different to the 1970’s and more intractable with current policy tools and the disaster that is the Euro. The first thing on policy makers agenda should be getting ‘weak’ countries to leave the Euro. Second, more repairs to banking systems (ie further recapitalisation) Third- I think the Swiss central bank has also pointed out the possible way ahead. It is not quantitative easing, it is negative interest rates with monetary systems that facilitate this. In the 1970’s high inflation permitted very negative real interest rates, which probably saved the world from a more difficult time.

That is surely a better option in terms of avoiding misallocation of real resources than more deficit spending like Bill suggests.

Apparently ‘stag-deflation’ was already coined by

Nouriel Roubini in 2008 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Deflation#cite_note-44

So no need to invent it 😉

Guardian blaming Britons for insane EU austerity policies as an excuse for unlimited immigration and claiming welfare is OK when we need a job guarantee:http://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2015/jan/19/-sp-thousands-britons-claim-benefits-eu

Mr. Mitchell,

Thank you for the post, but what other policy recourse to reduce demand and reduce unemployment, other than to increase taxes, reduce spending, or increase interest rates? Are you referring to a job guarantee, which would employ those who were sacked after the government-imposed reduction of aggregate demand? I fail to understand what other policy tools the government had available to achieve “some sort of consensual approach to sharing the costs of the imported raw material price rise.”

Sincerely, Joel

Whilst government sector deficit’s role in determining the level of private sector surplus

and effecting aggregate demand no doubt plays it part in the phenomena of

“stag deflation” it cannot be the main driver.The country that has experienced the most

prolonged period of “stag deflation” is the country that has been running the largest

government sector deficits-Japan.Crucially it is the country which has also experienced the

most protracted period of wage stagnation.

Markets are never free ,freedom to’s are at heart power to’s.Whether it is cost push or demand

pull inflation or deflation we are talking about power conflicts.Conflicts for resources via conflicts

for money tokens

Yes Marx accurately described a central conflict between capital and labour the struggle for

surplus value but that is one of many.For the purposes of inflation and deflation we have conflict

between capital and between labour between different sections of the economy and within

different sections of the economy.Of course the economy and life in general is not primarily driven

by conflict cooperation is the heart of civilisation and economic progress division of labour etc

Inflation and deflation reveals the conflict side.

So what developments have we seen between the era of the 70’s stagflation and today’s

stagdeflation yes Bill is absolutely right the central role was the paradigm shift in political economy

the rise of the “neo liberals” but just as” keyseniasm” was unable to prevent the cost push inflation

of the 70’s driven by the resource grab via money tokens of the OPEC oil cartel Japan’s historically

large peace time government sector deficits have not prevented a long period of stagdeflation.

What else has been going on. Massive resource grabs via money tokens by the very

rich via financial markets ,grabs by landlords and property speculators but most tellingly for deflation in

the developed world a collapse in the bargaining power of labour.

Globalisation has weakened the power of the majority in the developed world. It has not only been felt in

traditional industries .We have lost many of the relatively well paid blue collar jobs but these were in

a sense the vanguard of the working class powerfully unionised their loss becomes the majority’s loss.

We end up with entrenched external deficits combined with the politics of austerity and the inevitable

growth of credit consumption.

Yes the big winners of globalisation have been the very rich but workers in the developed world have

benefitted too from escape from the poverty of agricultural labour.How to insure the majority in the

developed world can resume their progress which seemed natural during the post war settlement

the “never had it so good days” yes government sector deficits are crucial but as Japan shows not enough

I do not think even job guarentees are enough in the struggle for resources via money tokens.

«address the incompatible demands for more national income from labour and capital by seeking some sort of consensual approach to sharing the costs of the imported raw material price rise.»

That is a fine moral sentiment, but there is abundant proof that in many cultures it does not work: it was tried in the USA, the UK and many european countries and failed.

In the UK it was tried by a Labour government that had the full support of the trade unions.

Unfortunately those trade unions could not even arrange a consensus among themselves; the trade unions that thought they controlled the most critical industries with the strongest monopoly and rent positions pushed hard to use that power to protect their members, throwing all other workers under the bus.

This fatally damaged the trade union movement and made trade unions and strikes very unpopular: workers in critical industries like energy, air traffic control, ports, rubbish collection, etc. were pushing down in effect workers in other industries. Plus they also made their lives miserable.

Many workers understand that strikes are the only effective way to protect and enhance their working conditions; but they also realized that other workers in critical industries can use them savagely, and thus decided that it was better to outlaw strikes in general and suffer the consequences as the lesser of two evils.

«lost many of the relatively well paid blue collar jobs but these were in

a sense the vanguard of the working class powerfully unionised their loss becomes the majority’s loss.»

It turned out that many of «the well paid bluer collar» workers were not the vanguard of the working class but really the rearguard of the rentier class when they started striking to protect from the worsened terms of trade after the oil price boom. They were the “Blow you! I am allright Jack” categories that thought nothing of other workers.

«the importance of countries having their own freely floating currencies, and, in this scenario, the impossibility of their becoming insolvent»

I hope that our blogger never said that and I am pretty sure that he never said that because that’s really wrong.

Countries that print their own currency can become insolvent:

* If they have issued debt in other currencies because nobody will *freely* lend to them in their own currency.

* When they decide to voluntarily stop paying debts in their own currency, for example to prevent inflation or a fall in the exchange rate.

Countries that issue debt in their own currency don’t get magical powers: because they have first to get their currency *accepted* by their creditors.

There are plenty of examples of countries that cannot issue debt in their own currency because it is not accepted by creditors, or that issued debt in their own currency and then made it unacceptable by inflating it way, and even examples of countries that did not pay debt issued in their own currency.

Put another way the only magical power that countries get from issuing debt in their own currency is to become able to renege on their debt “de facto” rather than formally by making their own currency unacceptable, but that is a magical power that they can exercise only rarely or rather gradually, as their creditors are not always stupid.

«The falling prices are what economists would call a reverse supply-side (cost) shock – a favourable one. Consumers will have more disposable income and firms will have lower unit costs. So why wouldn’t that invoke optimism? The answer is obvious. Any beneficial impacts from the supply-side of the world economy are being offset by the demand-side contractions brought about by on-going fiscal austerity. Even with deflation, firms will not hire and expand production if they do not expect the sales environment to be favourable in the immediate future. Firms hire workers to produce goods and services for sale. They will not employ to produce unsold inventories no matter how cheap labour or other essential raw material inputs becomes.»

That seems to be moderately absurd as other people have pointed out, and an application of “tricke-down” logic applies to macro demand.

On a global level a reduction in the price of oil transfer real income from oil producers to to oil consumers, so it has no direct effect on global demand unless the demand profiles of oil consumers and producers are very different. If the oil consumers tend to have lower saving ratios than the direct effect is actually to boost the demand for oil and services and reduce the demand for securities.

The case where “austerity” in oil consuming countries has an effect is when oil consumers use the income transferred to them by oil producers not to spend more but to pay down debt, and the beneficiaries of the debt repayments have a lower demand profile than the oil consumers, which is likely.

But the alternative is for oil consumers to spend their higher real incomes on more consumption leaving their debt levels unchanged. But this depends on whether debt is a problem for them or not.

So in the case where “austerity” means “pressure to repay debt instead of defaulting on it” and oil producers have a higher demand profile then a redistribution of income from oil producers to oil consumers drags down global demand.

But this assumes that private debt in oil consuming countries is not a problem and can remain as large as it or increase without effect.