I grew up in a society where collective will was at the forefront and it…

The loaded language of austerity – but all the sinners are saints!

The US National Institute of Justice tells us that – Recidivism is “is one of the most fundamental concepts in criminal justice. It refers to a person’s relapse into criminal behavior, often after the person receives sanctions or undergoes intervention for a previous crime”. You know murder, rape, theft, and the rest. According to the European Commissioner for digital economy and society and Vice-President German Günther Oettinger running a fiscal deficit above 3 per cent when you economy is mired in stagnation is a criminal act! This religious/criminal terminology is often invoked. German Finance minister Wolfgang Schäuble told the press before a two-day summit in Brussels in March 2010 on whether there should be Community support for Greece, that “an automatic system that hurts those who persistently break the rules” was needed to punish the “fiscal sinners”. This sort of language, which invokes metaphors from religion, morality and criminology is not accidental. Especially in Europe, where Roman Catholocism still for some unknown reason reigns supreme in society, tying fiscal deficits to criminal behaviour or sinning is a sure fire way of reinforcing the notion that they are bad and should be expunged through contrition and sacrifice. The benefits of fiscal deficits in circumstances where the non-government sector is saving overall are lost and the creation of the metaphorical smokescreen allows the elites to hack into the public sector and claim more real resources for themselves at the expense of the rest of us.

In 2012, Oettinger had toyed with the German press about the possibility that Eurozone nations which had been bailed out by the Troika should be forced to fly their national flags at half-mast right across the EU (Source).

At the time, an Irish Labour party representative called Oettinger a “myopic bully”.

In his latest outburst, Oettinger wrote an Op Ed for the French newspaper, Les Echos (November 20, 2014) – Déficit de la France : le coup de semonce d’un commissaire européen (French deficit: Warning shot from European Commissioner).

In that article, he claimed that France was a “deficit recidivist” (“déficitaire récidiviste”). He also spun the line that austerity has solved the crisis in Europe.

He wrote:

Reconnaissons-le: la profonde crise de confiance dans l’euro, qui a semé la crainte pour leur épargne chez des millions de citoyens et a ébranlé la quasi-totalité de notre système économique, a été surmontée grâce aux énormes efforts des États membres, pays débiteurs aussi bien que créanciers, et à la coopération fructueuse mise en place avec les institutions de l’UE. Le fait d’avoir jugulé cette crise ensemble est indéniablement une réussite.

Which amounts to him saying that the crisis has been overcome thanks to the enormous efforts of the Member States … and the cooperation with the EU institutions. He said that they have been successful in curbing this crisis together.

This is at a time – nearly 7 years later – that the talk is of a triple-dip recession and unemployment remains above 20 per cent in some nations.

But it hasn’t all been success according to the German. The intent of his article is that France is dragging the Eurozone down because it refuses to hack into income support systems, public sector employment, regulations that protect the environment, workplace safety, job security, and wages overall.

Interestingly, the article was recycled in the Financial Times on the same day (November 20, 2014) under the title – Europe’s economic future depends on French reforms.

The language was less strident. Gone was reference to recidivism and instead the issue was euphemistically expressed in this way:

But so too will be the more immediate question of how strict the European Commission is in addressing the issue of France and its high budget deficit.

The demands by the Commission that France impose even harsher cuts because it has been acting like a criminal were dressed up as:

France must commit to policy goals that can solve its economic and fiscal problems in the long term.

This should not be seen as a decision taken against France but rather as a measure for, and with, France. It is not just about one country. Without an economically strong France, the eurozone as a whole will not recover.

He claimed that France had to cut labour costs (aka hack into wages), slash red tape (aka letting business get away with blue murder) and cut company tax rates (aka letting business take even more real income from the workers).

Oettinger thinks growth will come from “deep structural reforms” in France, the familiar mantra.

I covered the struggles that France is having with the European Commission in this blog – Eurozone battle lines being drawn again with Germany on the other side.

Since I wrote that blog, Italy has surrendered but listening to a senior politician in Florence last Saturday you wouldn’t believe that. According to him, Italy is leading Europe to a more prosperous future. Tell that to the beggars that swarm around the railway stations and streets in Italian cities. And see below for how well Italy is doing.

The EUObserver article (November 21, 2014) – German commissioner provokes French wrath – suggested that Oettinger was doing the dirty work for the new Juncker cabinet. The hard cop routine.

As an aside, Jean-Claude Juncker, the new EC boss is being investigated for overseeing the tax avoidance schemes that emerged in Luxembourg during his period as Finance Minister and Prime Minister. He denies everything, of course. But it is clear the schemes started about the same time as he became the Finance Ministers and insiders have given statements that he knew what the Tax Office was doing and never intervened.

Not yet in the job for a month, there are calls for his resignation over the tax scandal.

But the language used by these conservatives is important in pushing there ideological agenda and diverting the public debate, media coverage and public understanding away from what is actually going on and what the solution to the stagnation would actually require (much higher fiscal deficits in all Eurozone nations).

I gave a talk at the Rome Tre University on Monday about the way framing and language is used by neo-liberals to reinforce economic concepts that have no foundation in reality. This blog from December 2013 discussed the preliminary work we have done in this area – Framing Modern Monetary Theory – which was based on this – Paper.

As part of that presentation I contrasted two visions of the economy, which was inspired by the work done by Shenker-Osorio in her 2012 book – Don’t Buy It: The Trouble with Talking Nonsense about the Economy.

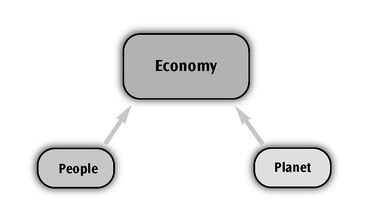

The first figure represents the conservative, neo-liberal view, where the basic assumption is that “people and nature exist primarily to serve the economy” (Shenker-Osorio, 2012: Location 439).

This narrative tells us that a competitive, self-regulating economy will deliver maximum wealth and income if ‘allowed’ to operate with minimum intervention.

The economy is figured as a deity that is removed from us though it recognises our endeavours and rewards us accordingly. We are required to have faith (confidence), work hard and make the necessary sacrifices for the good of the ‘economy’: those who do not are rightfully deprived of such rewards. They are miscreants – recidivists – sinners!

The economy is also figured as a living entity. If the government intervenes in the competitive process and provides an avenue where the undeserving (lazy, etc.) can receive rewards then the system becomes ‘sick’.

The solution is to restore the economy’s natural processes (its health), which entails the elimination of government intervention such as minimum wages, job protection, and income support.

The key messages are ‘self-governing and natural’, which force the obvious conclusion that “government ‘intrusion’ does more harm than good, and we just have to accept current economic hardship” (Shenker-Osorio, 2012: Location 386).

Although subscribers to this view would have us believe this is a rational narrative, in fact it represents a type of ‘magical thinking’ more appropriately associated with medieval views on the relationship between individuals and the world.

In the orthodox view, the hallmarks of a successful country are whether real GDP growth is strong irrespective of the costs.

In the EMU context, price stability has been elevated to the top of priorities and the politicians judge success according to adherence to arbitrary financial ratios. They tolerate mass unemployment as if there is no choice.

And the ECB has even failed to meet its own inflation target – from below!

But in this vision, discipline and sacrifice are eulogised even as poverty rates rise and a generation of youth is rapidly becoming dislocated from the normal pathways that provide for individual prosperity and maintain social stability.

Of course, discipline is a moving feast. The banksters and financial elites have different rules for themselves about what sacrifice and thrift is required.

The narrative also teaches us that our own outcomes are dislocated from the success of the system and so success and failure are both represented as due primarily to our own efforts. Similarly, the unemployed are seen as being responsible for their jobless status, when in reality a systemic shortage of jobs explains their plight.

This narrative is so powerful that progressive politicians and commentators have become seduced into offering ‘fairer’ alternatives to the mainstream solutions rather than challenging mainstream assumptions root-and-branch.

For example, progressives timidly advocate more gradual fiscal austerity when they should be comprehensively rejecting it on the basis of evidence that it fails, and advocating larger deficits to solve the massive rates of labour underutilisation that burden most economies.

The euro Groupthink is so strong that progressives design all sorts of solutions to the crisis that will preserve the euro, when in fact it is the euro that is the problem.

Progressives and conservatives are hostage to the same erroneous beliefs about the way the economy operates; yet the public is compelled to believe there is no alternative to the damaging economic policies being introduced.

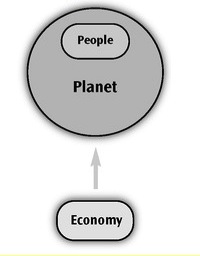

The second figure represents an alternative view of the economy, where the economy works for us as our construction and people are organically embedded and nurtured by the natural environment.

Shenkar-Osorio (2012: Location 1037) says:

This image depicts the notion that we, in close connection with and reliance upon our natural environment, are what really matters. The economy should be working on our behalf. Judgments about whether a suggested policy is positive or not should be considered in light of how that policy will promote our well-being, not how much it will increase the size of the economy.

In this view, the economy is seen as a ‘constructed object’ and policy interventions should be appraised in terms of how functional they are in relation to our broad goals, which a progressive vision would articulate in terms of advancing public wellbeing and maximising the potential for all citizens within the limits of environmental sustainability.

The focus shifts to one of placing our human goals at the centre of our thinking about the economy.

This perspective echoes the principles of functional finance developed by Abba Lerner. Please read my blog – Functional finance and modern monetary theory – for more discussion on this point.

Consistent with this, Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) highlights the irrelevance of a narrow focus on the fiscal balance without reference to a broader human context.

In this narrative, people create the economy. There is nothing natural about it. Concepts such as the ‘natural rate of unemployment’, which imply that it should be left to its own equilibrating forces to reach its natural state are erroneous.

Governments can always choose and sustain a particular unemployment rate. We create government as our agent to do things that we cannot easily do ourselves and we understand that the economy will only serve our common purposes if it is subjected to active oversight and control.

The Government (or the European Commission) is not a moral arbiter – sentencing criminals or admonishing sinners.

The EMU was created by human effort and can be dismantled accordingly. The union is not irrevocable and the euro is not irreplaceable.

The claim that Europe would plunge back into a new ‘dark age’ if a single nation abandons the euro and restores its own currency sovereignty is simply Groupthink polemic.

The two visions of the economy can be summarised in value terms as individualistic (neo-liberal) and collectivist (progressive).

For a progressive, collective will is important because it provides the political justification for more equally sharing the costs and benefits of economic activity. Progressives have historically argued that government has an obligation to create work if the private market fails to create enough employment.

Accordingly, collective will means that our government is empowered to use net spending (deficits) to ensure there are enough jobs available for all those who want to work.

The contest between the two visions has spawned a long-running debate in the academy.

It played out during the Great Depression, which taught us that policy intervention was elemental in order to reign in the chaotic and damaging forces of greed and power that underpin the capitalist monetary system.

We learned that so-called ‘market’ signals would not deliver satisfactory levels of employment and that the system could easily come to rest and cause mass unemployment.

We learned that this malaise was brought about by a lack of spending and that the government had the spending capacity to redress these shortfalls and ensure all those who wanted to work could do so.

From the Great Depression and responses to it we learned that the economy was a construct – not a deity – and that we could control it through fiscal and monetary policy in order to create desirable collective outcomes.

The Great Depression taught us that the economy should be understood as our creation, designed to deliver benefits to us, not an abstract entity that distributes rewards or punishments according to a moral framework. The government is therefore not a moral arbiter but a functional entity serving our needs. Our experiences during the period of the Great Depression led to a complete rejection of neo-classical macroeconomics (the forerunner of the modern neo-liberal variant).

The solution to the Eurozone crisis is not for France to undermine the social progress in wage levels, public services etc that have been achieved over the years. Rather it is simply that the French government spend more in net terms – that is, increase its deficit.

We switched from that understanding after the OPEC oil price hikes in the 1970s which provided the switch point that saw the conservative ideas represented regain ascendancy, despite them being cast into disrepute during the 1930s by the work of Keynes and others.

We cover that transition in detail in our 2008 book – Full Employment abandoned.

The ways in which governments around the world have responded to the GFC, in contrast to responses to the Great Depression, offer insights into the extent to which orthodox economic rhetoric has come to define economics as a profession and the public’s understanding of the policy options that flow from this, guiding societies away from a model of the economy that serves to maximise collective well-being.

The resurgence of the free-market paradigm has been accompanied by a well-crafted public campaign where framing and metaphor triumph over operational reality or theoretical superiority.

This process has been assisted by business and other anti-government interests, which have provided significant funds to emergent conservative, free-market ‘think tanks’.

Politicians parade these so-called ‘independent’ research findings as the authority needed to justify their deregulation agendas. Multilateral organisations such as the IMF also continue to distort policy debates with their erroneous claims and, in the case of the IMF, incompetent and error-prone modelling.

And then senior EU officials invoke this loaded language to perpetuate the malaise.

Meanwhile, the US has updated its GDP growth figures for the third-quarter which shows real GDP grew in seasonally adjusted terms by 3.9 per cent in the previous year. The preliminary estimate had been 3.5 per cent. If we annualise the last two quarters’ growth then the rate would be 4.25 per cent, which is sufficient to eat into official estimates of unemployment.

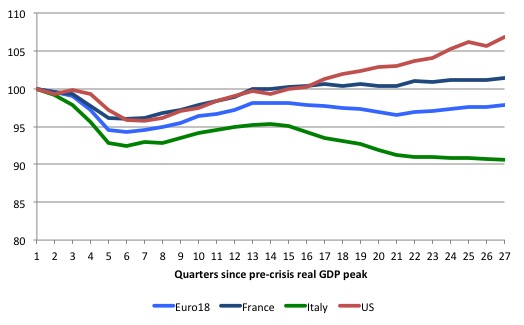

Compare the following graph. It shows real GDP indexed to 100 at the first-quarter 2008 for the Eurozone, France, and the US.

The base quarter 100 is the peak for each series that was achieved before the crisis. So for Europe it was the March-quarter 2008, whereas for the US it was a quarter earlier (December 2007). The numbers on the horizontal axis are quarter after the peak.

The cycles were closely linked in the downturn and early stages of the recovery. Fiscal deficits in all countries (regions in the case of the Eurozone) were expanding through a combination of automatic stabilisers (cyclical response arising from lost tax revenue and increased welfare payments) and varying degrees of discretionary fiscal stimulus.

The recessions were deep in all cases (deeper in Italy) and the recoveries slow, which indicates that the expansion in the government deficits were insufficient to offset the decline in non-government spending.

But after some period the growth experience diverged with the US leaving the European economies behind. While the former has largely moved ahead in a consistent (albeit modest) fashion, the European economies have faltered. In Italy’s case, the recession is intensifying.

Growth has stalled for France and the Eurozone, generally, is in stagnation, still well below the peak of the March-quarter 2008 – more than 6 years later.

The difference is that dysfunctional political system in the US throughout this period has meant that the fiscal deficit remained relatively large for much longer and supported growth while the private sector regained confidence.

There is now evidence that US private sector credit growth is starting to accelerate – see the most recent – Household Debt and Credit Report – published by the US Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

It shows that:

As of September 30, 2014, total household indebtedness was $11.71 trillion, up by 0.7 percent from its level in the second quarter of 2014, an increase of $78 billion.

In stark contrast has been the behaviour of European governments driven by the mindless Stability and Growth Pact rules and its related ad hoc modifications.

Once Europe’s austerity mindset was imposed there was no hope for growth given the state of non-government spending. All the claims by the European Commission and the IMF etc that there would be a fiscal contraction expansion were lies.

That is now clear, even though it was obvious to anyone who understand even the smallest amount about the way economies work.

It was just a smokescreen to drive the workers into submission and finally create the conditions where government services and income support schemes (including pensions) could be hacked into as the next big push to cement the hegemony of financial capital.

Conclusion

The European Commission is to meet this week to discuss the French case. If they impose even harsher conditions on the nation and it obeys then recession in France is inevitable (replacing near zero growth).

If France doesn’t obey then we are back to 2003, which should be interesting.

One hopes that the French don’t replicate Italy and talk big but when the pressure is put on them, surrender to the neo-liberal austerity.

The fact that France has refused to date to cut its deficit in the time period specified by the Commission makes them saints or to invoke the great Rolling Stones line “all the sinners saints”!

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2014 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

I think it is more suitable to summarize both strategies as competitive versus cooperative.

(long-term) Individualistic and collective goals do not necessarily conflict with each other. The individualism in neo-liberal economics is deceptive as it only takes into account relative prosperity of the individual rather than the absolute one.

Dear Mr. Mitchell,

Thank you for your post. I think you do a very valuable public service but I have one minor issue: I think the obsession with debt is a very Protestant thing as opposed to Catholic. The work-hard-and-be-rewarded is almost literally enhrined in that religion, which also Weber noticed in “The Protestant ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism” (although I don’t think capitalism doesn’t quite come from there..). I might have to do some research but I think this obsession with debt-as-morality is a reaction to the Catholicism of its day, with all its gold and glitter and corruption.

It boils down to money and power.

So the question we need to ask ourselves is who would benefit from a change in the way things are organised. Who would be prepared to fund the marketing and PR campaign necessary to get the correct view out there on the understand they would benefit afterwards once you have removed the banks and the large corporations from their current position of power.

I was hoping we’d get some sense out of geek culture, but it seems that they are off indulging in anarchy at the moment – hence the Russell Brand position.

In fact it would be useful to address why ‘social anarchy’ couldn’t really work in a modern world given nature of power and the requirement of the monetary system. I struggle to see how it could avoid severe deflation due to the paradox of thrift.

I like this South Park scene from the Shenker-Osorio book. Sounds like Jens Weidmann lecturing the citizens of the Eurozone.

Neil,

I suggest you would have less problems with Anarchy as Noam Chomsky frames it. Democracy seems to run counter to anarchy but it is a perfectly acceptable position to accept forms of authority that can justify themselves to the public or be content to dismantle themselves when they cannot.

I do see some potential problems with tax offices and central banks in such a system, but have no doubt that there are enough intelligent people in the world to propose a working form of anarchist democracy/socialism that addresses these institutions and the role they would need to play.

“there are enough intelligent people in the world to propose a working form of anarchist democracy/socialism ”

That’s a delusion I’m afraid. One that is currently shared by many systems people it would seem.

The reality of all ape tribes is that there is always a big ape – a big man, and it is nearly always a a man – who becomes dominant. That is the nature of the species.

The state is there to be the big man and stop any others rising up to replace it.

We can already see how anarchy pans out. You just have to go to Africa and see how all the little tribes never get together and achieve any progress. The result is an Ebola epidemic in the more chaotic Western African nations, and proper health controls and no Ebola in the nations that can garner a social response because they have an effective state.

Anarchy is another pipe dream – based on the myth that all people are all built like you. They are not. Systemically it doesn’t work because humans are not robots – just like for citizens income, free markets and all the other liberal thought experiments about how wonderful it would be if humans were not apes.

Rule #1 – it has to work with a bunch of bipedal apes, half of which aren’t intelligent by definition.

Neil,

Not so much deluded as optimistic. Anarchism will never exist in steady state – there will always be megalomaniacs but it is all about the electorate’s ability to spot them and knock them off their podium before they cause too much damage. Power structures and leaders may not be preferred but would certainly be tolerated as long as they appear to have the population’s best interests at heart.

The idea of anarchism as a permanent stateless society on a large scale IS deluded, but there could certainly be periods of time, nationally or locally, where the population is capable of self-direction, and more capable than any available leadership of the time.

Political powers must not be allowed to grow too large, and the same goes for economic power. A public banking option would go a long way to aiding this cause, as would frequent referendums, and the fostering of workers’ co-operatives.

It is funny how language shapes thought. The word for “debt” and “guilt” in German is the same – “schuld”. Hence Herr Oettinger naturally believes in severe punishment of “recidivist” debtors.