It is true that all big cities have areas of poverty that is visible from…

Britain has not recovered the losses caused by the GFC

As a followup to Monday’s blog – UK growth not all that it seems – there was an additional issue that is worth exploring about the ONS data publication, given that the financial and economics commentators seem to mislead their readers, through ignorance or choice. Representative of the issue was the statement in last Friday’s UK Guardian article (July 25, 2014) –

Fresh boost for George Osborne as economy recovers banking crisis losses – which built on that title with the opening line “Britain’s economy has finally recovered the losses caused by the financial crisis, passing its pre-recession peak in the second quarter of the year …”. This conclusion was reiterated by many other commentators in different publications as a source of celebration. The only problem with it is that it plain wrong and to suggest that Britain has now made up the losses is deeply misleading.

While Britain’s real GDP is now just above the March 2008 level the question of losses is not simply about regaining the size of the economy.

For each day that real GDP was below the potential real GDP (that is, the productive capacity) there is a loss and those losses are never regained. They are lost forever.

The longer that real GDP remains below its potential, then the greater are those cumulative losses. So it is incorrect to conclude as the Guardian article did, for example, that Britain “has finally recovered the losses”. That is not even close to the truth.

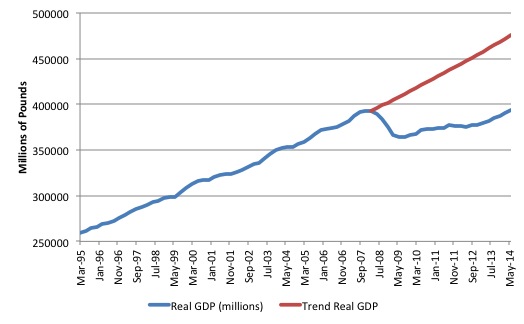

The following graph shows real GDP from the March-quarter 1995 until the June-quarter 2014. The red line is just an extrapolation based on the average quarterly growth rate between March 2003 and March 2008, which signifies the trend that the British economy had been on, give or take some blips here and there.

The difference between the two solid lines is called the output gap because it tells us how far below the potential the economy is operating. Clearly the output gaps have been very large in Britain since mid-2008.

The red line might be considered to be potential output had not the crisis occurred and that would be conservative. Why? Because it assumes that the peak real GDP quarter in March 2008 before the crisis was a full capacity quarter. That is, the following assumes there was zero spare capacity in the British economy in March 2008.

There was but it doesn’t really alter what we conclude here.

Using that assumption then the current deviation between potential GDP and actual real GDP is some 17.2 per cent, a huge output gap. The cumulative loss by the June-quarter 2014 would be 3.67 times larger than the current level of real output in Britain.

That gives you an idea of how deep this recession has been.

The problem is that the longer the recession the more damage is caused and at some point, the productive potential of the economy shrinks.

In other words, the output gaps will shrink even though the economy is still in a deep recession because of that shrinking potential. We always have to be on our guard when organisations such as the IMF and the OECD start talking about how the output gaps have declined, as if that is a good thing.

It is one of those concepts in macroeconomics where ambiguity reigns. It is not a simple measure because it can become smaller for good and bad reasons just as it can become larger for good and bad reasons.

A declining output gap that is associated with an acceleration in total spending, which, in turn, creates stronger employment growth is a good thing. The same narrowing associated with a decline in the productive potential of the economy as a result of declining investment is a bad thing.

This relates to the concept of hysteresis in economics, which means the present is a function of the path that the economy has taken to get here. Some people talk about path-dependence to describe this phenomenon. My PhD was partly about this concept and embedded the notion in some of my earliest MMT-style writings.

Hysteresis is a term drawn from physics and is defined by the Oxford Dictionary as :

… the phenomenon in which the value of a physical property lags behind changes in the effect causing it, as for instance when magnetic induction lags behind the magnetizing force.

My early work in the mid-1980s, which was a critique of the neo-liberal mainstream arguments about ‘natural rates of unemployment’ was based on the strong empirical observation that many perceived ‘structural imbalances’ are, in fact, of a cyclical nature. Accordingly, a prolonged recession may create conditions in the labour market which mimic structural imbalance but which can be redressed through aggregate policy without fuelling inflation.

Please read my blog – IMF attacks the Stability and Growth Pact – for more discussion on this point.

The importance of hysteresis as a concept in economics is that it challenges the mainstream notion that the long-run is independent of the short-run. For the layperson, this might be represented by the claim that pursuing some low inflation target no matter how much unemployment is created is not a problem because in the ‘long-run’ the unemployment will be at the ‘natural rate’ anyway. Of-course the notion is nonsense.

The long-run is thus never independent of the state of aggregate demand in the short-run. There is no invariant long-run state that is purely supply determined. History is a series of interlinked (co-dependent) short-runs.

By stimulating output growth now, governments also help relieve longer-term constraints on growth – investment is encouraged and workers become more mobile.

The problem compounds though, because the supply-side of the economy (potential) is influenced by the demand path taken and the longer is a recession (that is, the output gap), the broader the negative hysteretic forces become.

At some point, the productive capacity of the economy starts to fall towards the sluggish demand-side of the economy and the output gap closes at much lower levels of economic activity.

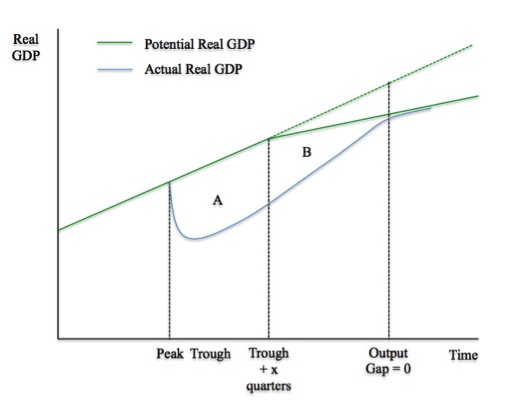

The following diagram shows how the demand-side and supply-sides interact following a recession to and helps us to understand the long-run losses. Unlike the mainstream macroeconomics approach, which assumes that the “long-run” is supply-determined and invariant to the demand conditions in the economy at any point in time, the diagram shows that the supply-side of the economy responds to particular demand conditions.

In terms of the following diagram, the potential output path is denoted by the green solid line noting the dotted green segment is tantamount to our red line in the above graph.

The potential output is the level of real output it would be forthcoming if all the available collective capacity (including Labour and equipment) was being fully utilised.

The diagram assumes, for simplicity, that potential real GDP assumes some constant growth in productive capacity driven by a smooth investment trajectory up until the point where it starts to flatten out.

If we assume that at the peak the economy was working at full capacity – that is, there was no output gap – then we can tell a story of what happens following an aggregate demand failure. The solid blue line is the actual path of real GDP.

You can see that the output gap opens up quickly as real GDP departs from the potential real GDP line. The area A measures the real output gap for the first x-quarters following the Trough.

As the economy starts growing again as aggregate demand starts to recover (perhaps on the back of a fiscal stimulus, perhaps as consumption or net exports improve) after the Trough, the real output gap start to close.

However, the persistence of the output gap over this period starts to undermine investment plans as firms become pessimistic about the future state of aggregate demand.

At some point, investment starts to decline and two things are observed: (a) the recovery in real output does not accelerate due to the constrained private demand; and (b) the supply-side of the economy (potential) starts to respond (that is, is influenced) by the path of aggregate demand takes over time.

Remember investment has dual characteristics. It adds to demand (spending) in the current period but adds to productive capacity in the future periods. It thus influences aggregate demand (now) and aggregate supply (later) – and that interdependency is crucial for understanding hysteresis.

As the recession endures, the capital stock of a nation either remains static or in extreme cases (such as Greece at present) it will contract.

The pessimism by firms begins to reduce the potential real output of the economy (denoted by the divergence between the solid green line and the dotted green line).

The area B denotes a declining output gap arising from both these demand-side and supply-side effects. At some point, actual real output reaches potential real output – meaning the output gap is closed – but the overall growth rate is much lower than would have been the case if the economy has continued on its previous real output potential trajectory.

The entrenched recession is thus not only caused major national income losses while the output gap was open but is also made that the growth in national income possible in this economy is much lower and the nation, in material terms, is poorer as a consequence.

Moreover, the inflation barrier (that is, the point at which nominal aggregate demand is greater than the real capacity of the economy to absorb it) occurs at lower actual real output levels.

The estimated costs of the recession and fiscal austerity are much larger than the mainstream will ever admit

The point of the diagram is thus that the supply-side of the economy (potential) is influenced by the demand path taken.

Those who advocate austerity and the massive short-term costs that accompany it fail to acknowledge these inter-temporal costs.

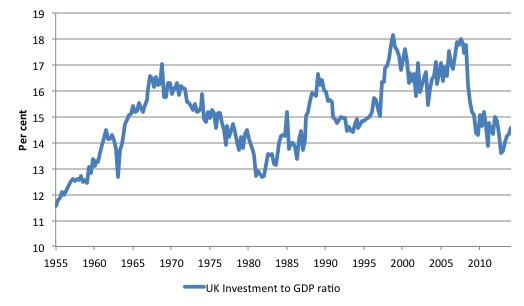

So clearly, the red line in the first graph is likely to be a fiction given the information that the next graph discloses. It is the investment ratio since the first-quarter 1955 to the first-quarter 2014.

There has been a massive drop in the ratio. Between March 2007 (peak) and December 2012 (trough) it fell by 4.3 percentage points. The only other time in this recorded history the ratio has fallen nearly as much was between December 1968 (peak) and September 1981 (trough) when it fell by 4.2 percentage points, but that was a much longer and slower decline.

Why does that matter? It matters because it is highly likely that the potential of the British economy has fallen, which magnify the losses that the lengthy recession has wrought.

It is still too early to say whether the current downward trend in the British investment ratio will alter course. Time will tell. But the plunge has been dramatic and will have definitely impacted on capacity building.

Chapter 3 Output and supply – in the Bank of England’s Inflation Report, February 2014 – bears on our discussion.

The discussion relates to how much “economic slack” there is in the British economy. The BoE’s conclusion is that:

Business surveys suggest that companies were operating at close to normal levels of capacity in Q4. But a margin of labour market slack remains.

Section 3.2 ‘Indicators of spare capacity’ analysed the “degree of inflationary pressure” in the UK economy in terms of the “balance between demand and supply”.

They analysed three different survey indicators of capacity utilisation:

- The Bank’s Agents measure – covering manufacturing and services.

- The British Chambers of Commerce (BCC) measure – covering non-services and services.

- Confederation of British Industry (CBI) measure – covering manufacturing, financial services, business/consumer services and distributive trades.

The – OECD Output Gap measures – are annual and measure Deviations of actual GDP from potential GDP as a per cent of potential GDP. They are computed analytically using models of potential output growth but still provide information of the degree of spare capacity.

Note that the OECD measures will always understate the output gap size because they assume full employment occurs at higher unemployment rates than would be reasonable.

The following graph shows the three survey based series used in the Bank of England’s inflation report and the OECD series. I just extrapolated the OECD annual series to fit the quarterly data by assuming the annual observation occurred in the last quarter of each year and then fitting the gap for the remaining 3 quarters in a linear fashion. Pretty standard.

Given the plunge in the investment ratio, it is almost beyond belief that some of the survey measures would suggest that firms have run out of capacity (above the zero line).

The Bank of England say that:

Surveys suggest that the margin of spare capacity within companies narrowed in 2013 such that companies were, on average, operating at close to normal levels of capacity utilisation … The interpretation of these survey measures is, however, not straightforward. Companies may have short-term notions of capacity in mind when responding to such surveys, ignoring, for example, mothballed capacity, which may require some spending to bring back into use. Moreover, while these surveys suggest that spare capacity within companies has, on average, fallen to more normal levels, most do not ask companies to quantify either current or ‘normal’ levels of capacity utilisation.

The CBI survey does ask firms to say how far below capacity they are operating but again the respondents claim to be operating around 82 per cent of full capacity which “broadly in line with the pre-crisis average”. Firms typically maintain some spare capacity so they can respond quickly to spikes in short-term spending and not lose market share.

The Bank of England also note that there is still considerable labour market slack in the British economy. They suggest that:

The fall in unemployment probably overstates the fall in labour market slack – the scope for total hours worked to increase without pressure on pay … Unemployment probably remains above its medium-term equilibrium rate suggesting scope for it to fall without significant pressure on pay.

And because their estimate of the “medium-term equilibrium rate” will be biased upwards, the slack is greater than they assume.

Overall, they conclude that there is “scope for companies to increase the hours their staff work without significant pressure on pay.”

The British Office of National Statistics also publish information on capacity utilisation. In its – Economic Review, March 2014 – published on March 5, 2014 they include a detailed analysis of different utilisation indicators.

The question that they consider (also covered in the Bank of England report) relates to the very poor productivity performance in the recovery period in the UK.

The ONS says that:

The recent fall in labour productivity is one of the defining characteristics of the UK’s economic performance in recent years. Output per hour often falls during economic downturns, but … the recovery of productivity since 2009 has been weaker than in any previous recovery of the last fifty years. The persistence of this productivity shock matters because of its implications for macroeconomic policy: if the fall in productivity is reversed as the economy gathers pace, then firms can both draw in new resources and use existing inputs more efficiently to meet growing demand. If the fall in productivity is permanent, then firms will only be able to call on finite new resources to meet the growth of demand. In this latter situation, economic growth is likely to raise inflation more quickly as firms use up spare capacity more rapidly. More precisely, the persistence of the productivity shock has implications for the potential for non-inflation accelerating economic growth.

So the output gap and capacity utilisation measures are clearly difficult to be definite about.

But the ONS concludes that:

… much of the spare capacity in the UK economy is in the labour market, as measures of unemployment and part-time employment are well above their long-run averages … suggesting that there are resources in the labour market which firms can mobilise to increase output. However, the extent of spare capacity within firms is much more limited: the extent of within-firm slack indicated by the Bank of England’s capacity constraint measure for manufacturing firms in particular is below its long-run average.

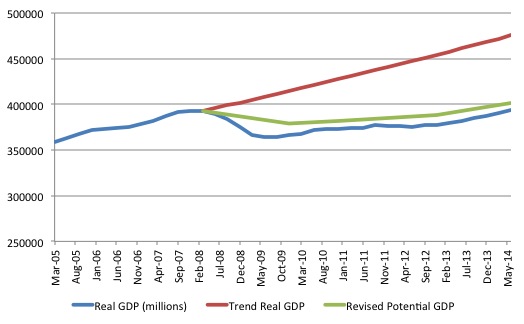

What does that mean for our first graph? It means that it is likely the true ‘red line’ is below the depicted red line. If, for example we assumed the output gap measure of the OECD was realistic, and we recomputed the potential output path from a zero gap in March-quarter 2008 to now (as the output gap has diminished) then the following graph would be produced.

The green line is the hysteretic decline in potential output implied by the OECD output gaps. It means that the short-run losses from the recession measured by the cumulative output gaps would be smaller but the growth and income-generating potential of the economy is massively smaller – meaning the cumulative losses are that much bigger.

The truth about potential output in Britain will lie somewhere between the read and the green lines, probably closer to the red line.

What does it mean for policy? If we were to believe that the within-firm capacity is nearly exhausted then the scope for stimulating private employment growth is limited until the investment ratio improves and labour productivity increases.

But given the slack that is identified in the labour market, the obvious solution is for large-scale public employment programs, which can be designed to use minimal capital requirements but perform productive functions and stimulate private sector investment.

Yes, the Job Guarantee is staring them in the face!

Conclusion

I am inclined to think that the real output gap in Britain is still substantial. The surveys are usually conservative (as noted by the Bank in the quote above) and the measures provided by the OECD and the IMF,for example, are always biased downwards.

There is definitely scope for expansion in the British economy and the first place to start would be to introduce a Job Guarantee. Then, apropos of the finding in Monday’s blog that the workers are not enjoying gains from the growth at present, the Government would ensure that income gains went directly to the unemployed and low wage workers that might prefer a Job Guarantee job over a nasty, low-paid private sector job.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2014 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Bill, there is hardly a commentator on economic issues working for the Observer/Guardian who seems to know what s/he is talking about. Even Larry Elliott, who is generally respectable on these matters often gets it wrong. The only two who come to mind off hand who are consistently ok in this respect are William Keegan and Aditya Chakrabortty, the former for the Observer, the latter for the Guardian. There are no doubt a couple of others but I just can’t think of them right now. Oftentimes, the letters page is more insightful economically. Rusbridger should start to think that this situation might just be scandalous for a national newspaper that projects an image that their content is of some intellectual quality and whose motto is “Fact are sacred”.

Part of the reason why their estimates of the ouput gap are understated might be because those estimates are pegged to the government’s inflation target. They forget that the inflation target is a rather arbitrary choice, that ignores the effect that high under-employment has on future potential GDP.

They would never say, for example, that compliance with the inflation target itself is destroying future GDP growth.

Bill, always a pleasure to read your analyses. I don’t know how you manage to write essay-length posts with substantial research, and publish them on a near-daily basis. But please keep it up.

What sort of tactics are available to refute the sloppy thinking often found in the news media and in classrooms? Sometimes it has the appearance of shouting at a wall.

Sincerely, Joel

Bill is operating under the delusion that the UK is some sort of closed production , distribution , consumption system which trades a bit of wool for wine.

I hate to break it to you but it gave up the wool trade for usury over 400 years ago.

Its a pure rentier economy of vast size and dastardly means.

It functions by extracting the income of its vassals by whatever means at its disposal.

See RBS type operations.

Exhibit A (Mini me British Euro vassal)

Irish Median Real Household Disposable Income (Euro) by Urban and Rural and Year

Urban areas

Y2004 : 40,056

Y2008 : 44,315 (peak)

Y2012 : 34,886

Rural areas

Y2004 : 30,717

Y2007 : 34,787

Y2012 : 30.337

They operate a zero sum game of extraction which has worked well until perhaps now.

Perhaps Irish incomes will increase again as for example tourists will move back into areas not already on Fire but the threat of another great war is a high price to pay don’t you think ?

In contrast to the Irish Spanish Greek etc etc et median income

ONS data.

“Since the start of the economic downturn, median household income and GDP per person have both fallen. However, the fall in UK median household income has been smaller than the fall in GDP per person over the same period. Between 2007/08 and 2011/12, median income fell from £24,100 to £23,200, a percentage drop of 3.8%, while GDP per person fell by 6.5%.”

“This may appear to be word

splitting, but when we realise that the whole of the industrial, legal, and social system of

the world rests for its sanctions on this theory of rewards and punishments, it is difficult

to deny the importance of an exact comprehension of it.

For instance, the industrial unrest which is disrupting the world at the present time, can

be traced without difficulty to an increasing dissatisfaction with the results of the

productive and distributing systems. Not only do people want more goods and more

leisure, and less regimentation, but they are increasingly convinced that it is not anything

inherent in the physical world which prevents them from attaining their desires; yet

captains of industry favourably situated for the purpose of estimating the facts, are almost

unanimous in demanding a moral basis for the claim put forward. That is to say, those

persons whose activities at the present time are chiefly concerned with restricting the

output of the economic machine to its lowest limit, while yet asking each individual to

produce more, are determined that not even the over-spill of production shall get into the

hands of a semi-indigent population, without some equivalent of what is called work,

even though the work may still further complicate (11) the problem with which these

industrial leaders are concerned. Nor is it fair to say that this attitude is confined to the

employing classes. Labour leaders are eloquent on the subject, and with reason. The

theory of rewards and punishments is the foundation stone of the Labour leaders’

platform, just as it is of the employer whom he claims to oppose. The only difference is

in respect of the magnitude and award of the prizes and as to the rules of the competition

for them. To any one who will examine the subject carefully and dispassionately it must

be evident that Marxian Socialism is an extension to its logical conclusion, of the theory

of modern business. ”

CH Douglas

A lack of jobs has nothing to do with the failure of the capitalist system.

We do not live in a agrarian economy Bill……….

The Uk is simply at the center (in particular the euro area) of the scarcity vortex.

“The second point is that, so far as we can

conceive, the co-operative industrial system cannot exist without a satisfactory form of

effective-demand system, and the result of an unsatisfactory money system (that is to say,

a money system which fails to function as effective demand to the general satisfaction) is

that mankind will be driven back to the distinguishing characteristic of barbarism, which

is individual production. And the third point, and the point which is perhaps of most

immediate importance at the present time, is that the control of the money system means

the control of civilised humanity. In other words, so far from money, or its equivalent,

being a minor feature of modern economics, it is the very keystone of the structure”

CH Douglas – speaking during the interwar years.

We are seeing a dramatic failure of the top down allocation of capital – chiefly via the bank credit vector.

A return of purchasing power at the base level will redirect physical capital inputs and thus the very structure of the production distribution and consumption system . i.e the Industrial system.

Bill,

I must admit that if there is one part of MMT theory I’m doubtful about, it is the JG. If the economies, of both the UK and Australia, were properly run we could could have virtually full employment. Just like we used to. There would then be no real need of a JG.

My concern is that any JG would be, in reality, just workfare but under another guise. The British Labour party are already planning for just that with their proposed “JG” scheme for 18-26 year olds.

Is this something you’ve already addressed in a previous posting?

A national Jobs program to defeat private sector low wages sounds good.What about a policy to tackle the extortionate high rents we have to pay.

Petermatin2001…..’properly run’ MMT policy solutions for an economy is to run a large fiscal deficit and have a jobs program to soak up excess labour that the private sector doesn’t use.