I grew up in a society where collective will was at the forefront and it…

Cutting US unemployment benefits is cruel and stupid

Once upon a time when I was a postgraduate student and there were around 10 unemployed for every registered vacancy in Australia a professor at my university was waxing lyrical about the lazy unemployed and what they should do to get off the welfare list. His said well “if they really wanted to work they could go down to the municipal tip and scratch together some scrap wood and some old pram wheels and build a cart, then follow the milkman around each morning and collect the horse dung and start a garden fertiliser business”. He wanted the unemployment benefit eliminated to get “these characters off their bums”. I remember the session vividly. That was his cure for the indolence of the unemployed. I put my hand up and said: “Two problems. First, the local council generally will not allow people to scour the tips for rubbish. Second, more importantly, the dairies now have trucks. The horse and cart milkmen were eliminated a few decades ago”. Much laughter followed. My relations with that professor soured a little more after that but the base (sourness) was already large so the percentage change was minimal. The same sort of idiocy is driving policy in the US at present with the US Congress enforcing more than a million unemployed Americans (that is, about 12 per cent of the total official unemployed) will lose their unemployment benefits this coming Saturday because the US politicians have decreed against all available evidence and research that this cohort is lazy and that the dole is standing between them and jobs.

There are two strands to this idiocy. First, there is an overbiding religious belief among mainstream economists that unemployment is largely a voluntary state and the choice to become unemployed is influenced (distorted) by the availability of income support payments. Take them away and job search activity will increase and the unemployed will be employed quickly.

Second, the mainstream economists claim that the income support payments add to an already unsustainable government spending crisis and are therefore better eliminated. I won’t discuss that nonsense today. It is obviously that the US Federal Government can always afford to pay the income support cheques.

The only thing it cannot guarantee is that the nominal monetary transfers will preserve a particular real standard of living, given that the government cannot be sure there will be enough real goods and services available at any point in time. But the nominal payment is not an issue.

The first of the unemployment benefit cuts will impact on those in receipt for five-years (that is, about 1.3 million long-term unemployed Americans).

Before long, hundreds of thousands more unemployed will enter the “banned” duration cohort and lose their benefits accordingly.

The amount being cut from Federal spending – you wouldn’t believe it – $US1,166 per month adding up to around $US26 billion per annum. Measly income support.

While the Obama camp might claim it is against the cuts, the fact remains that it agreed to them when it dealt with the devil – the manically stupid Republicans and the blue dogs from his own ranks.

The impacts will be fairly predictable:

1. Total spending in the US will fall (other things equal) and that will further undermine employment growth.

2. Some of the unemployment that have higher skills may compete for jobs at skill levels below them and deny the persons who would normally get these jobs access to them. This is called “bumping down” and happens when there is a tight ration on the total number of jobs in the economy. It is highly inefficient and means the really low skilled find it impossible to get work.

3. Given active search is a requirement for receiving the unemployment benefit at present, the elimination of the latter will terminate the former, meaning that tens of thousands will exit the labour force and enter inactivity. This will have the effect of reducing the official unemployment rate (other things equal) and if this impact is dominant, the conservatives will rejoice and tell us that they told us so.

We have already seen some trials of the impacts. The state of North Carolina eliminated benefits in July 2013 and the unemployment rate fell from 8.9 per cent to 7.4 per cent in November (see BLS series LASST37000003). Unemployment fell by 74,617 over the period.

Over the same period, the labour force shrank from 4,696,880 persons to 4,658,113 persons, a decline of 38,767 (see BLS series LASST37000006), employment rose from 4,278,652 to 4,314,502 (see BLS Series LASST37000005), and official unemployment fell from 418,228 in July 2013 to 343,611 in November (see BLS series LASST37000004).

So more than 50 per cent of the decline in unemployment arose because workers gave up looking for work in a very subdued labour market.

Is that good? Not at all!

Since January 2003 (including the recession), the labour force in North Carolina has grown at an average rate of 1.1 per cent per annum and employment growth averaged 0.80 per cent per annum.

If you consider the period January 2003 to December 2006, the respective annual growth rates were 1.7 per cent and 2.3 per cent.

Since the elimination in unemployment benefits (July 2013) the labour force has shrunk at an annual rate of 1.4 per cent and employment has grown at 0.09 per cent (that is, hardly at all).

As a rough (back-of-the-envelope) calculation, if the labour force had have been growing at its pre-crisis strength then the fall in the unemployment rate would have 8.65 per cent in November 2013 instead of 7.4 per cent. In other words, it would have fallen from 8.9 per cent to 8.7 per cent (around 9,266 persons).

So the fall in unemployment in North Carolina might have been engineered by the elimination of the unemployment benefits but the problem of inadequate jobs growth didn’t go away – it was just shifted to the discourage workforce that is counted outside of the official labour force.

It is highly likely that some of the unemployed who gained jobs bumped out lower skill workers from their normal job opportunities.

There are two good sources of US data which provide essential information about the state of the labour market in the US. First, the US Bureau of Labor Statistics – US JOLTS database, provides detailed information about job openings and quit rates, which allows an assessment of the strength of labour demand relative to supply to be made.

Second, the gross flows data which allows us to compute probabilities of labour market transitions – for example, from being unemployed to getting a job. I won’t consider this data source today but maybe later in the week as it has just been recently updated.

The JOLTS data allows us to explore the evidence-base for the view that “unemployment is a deeply entrenched supply-side problem” and that the provision of “unemployment benefits increases unemployment”.

The summary of the evidence I provide in this blog is simple. The view that there are plenty of jobs available in the US and the income support payments undermine people’s determination to take those jobs is entirely false and is illogical in theory and has no empirical support in practice.

That response doesn’t mean I ignore or exclude supply-side issues (lack of skills etc) as being part of the solution. But all the supply-side policies that work do so when they are applied in the context of paid employment.

Structural change (such as improving skills, encouraging mobility into bouyant regions etc) is largely ineffective when the labour market is weak. There have to be jobs for people to transition into.

The mainstream continually invokes the imagery that somehow the demand and supply-sides of the labour market are independent of each other. That allows them to define neat equilibrium solutions which lead them to telling economics students that wage cuts and pernicious welfare-to-work remedies are required to cure mass unemployment.

I love the JOLTS database because it in such a simple way provides incontrovertible evidence of how wrong the supply-side conception of mass unemployment is – all in a few time series.

There is no credible theory that relates starvation with an increased capacity to gain employment when the economy is some millions of jobs short of the level necessary to provide work for all those who desire it.

Forget the smallest margin of unemployed who do not want to work. They are of a second-order of smallness that doesn’t warrant attention. The overwhelming majority (comprising millions of citizens) want to work but cannot find work because it is not to be found.

Good policy does not punish the fortunes of the 99.5 per cent (or whatever) just to get at the recalcitrant 0.5 per cent. Conservative policy is typically built on such a blind hatred for the 0.5 per cent of people who skive the system (from the bottom income levels I should add) that the policy interventions hurt the vast majority.

Of course, the Conservatives never seek to sort out the 1 per cent at the top of the income distribution that are up to all sorts of tricks that undermine the integrity of the economic system.

But cutting income support when there is no other alternative is very stupid. The entrenched unemployment in the US is a sign there is a lack of overall spending in the economy.

Firms create employment in response to demand for their products. They might be confronted by millions of desperately hungry workers who have just had their benefits cut but they still won’t put them on because there is insufficient demand to justify expanding production.

A latent or notional demand for a crust of bread is not a demand backed by cash! Mainstream economists have never really understood that. Marx knew it. Keynes and Kalecki knew it. Clower and Leijonhufvud elaborated on it again in the 1960s but the conservative, free market types couldn’t see past Say’s Law!

Further, the fact that these cuts are now at the federal level means that if there is a widespread cut in benefits, then sales will drop and unemployment will rise not fall because aggregate spending declines.

Then it will depend on the relative magnitudes of the supply-contraction in the labour force (as workers give up looking) and the demand-contraction in employment as to whether the unemployment rises or fall. But whatever the relative impacts are, both are BAD!

My last blog on the US JOLTS database was – Cutting unemployment benefits in the US will not decrease unemployment.

Here is some evidence of what is going on.

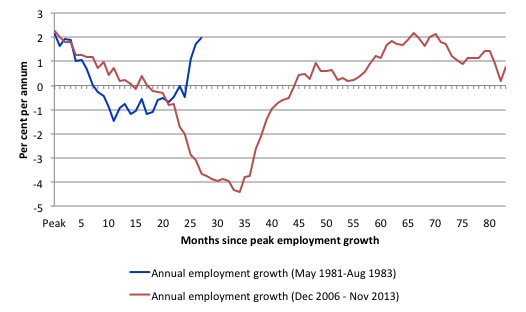

First, employment remains very weak. The following graph shows annual employment growth (per cent) in the months after the peak in the 1981 recession and the most recent recession.

The peaks before the respective crashes were similar (2.1 per cent in May 1981 and 2.3 per cent in December 2006).

The 1981 recession reestablished the peak employment growth after 27 months, and that was a fairly long recession when employment growth is considered.

You can see that the most recent crisis bottomed out much later and was much deeper and the recovery has been much slower.

Further, despite going close in month 66 and again in month 70 (in June and October 2012, respectively), the current cycle is yet to return to the modest peak reached in December 2006.

And now the economy is having to deal with a contraction which will get worse once the impacts of the withdrawn unemployment benefits manifests.

Second, unemployment cannot be explained by counter-cyclical quit behaviour.

The mainstream textbook models which underpin the claims that unemployment benefit provisions undermines search behaviour is based on the claim that federal income support for the unemployed destroys the, already weak, initiatives of the recipients and should be cut (or abandoned altogether).

The narrative promotes socio-pathological policies, which undermine the viability of the unemployed to live even the most modest material life, and dress these indecencies up as strategies to incentivise the jobless to do more to look for work.

The supply-side story starts with the textbook model of the labour market which claims that employment and the real wage are determined in the labour market at the intersection of the labour demand and the labour supply functions.

The equilibrium employment level is constructed as full employment because it suggests that every firm who wants to employ at that real wage can find workers who are willing to work and every worker who is willing to work at that real wage can find an employer willing to employ them.

Frictional unemployment is easily derived from this Classical labour market representation, as is voluntary unemployment.

Holding technology constant, all changes in employment (and hence unemployment) are driven by labour supply shifts. There have been many articles written by key mainstream economists (such as Milton Friedman) that argue that business cycles are driven by labour supply shifts.

The essence of all these supply shift stories is that quits are constructed as being countercyclical – that is, rise when the economy is in decline and vice-versa – despite all evidence to the contrary.

They have to argue this because the shifts in employment have to come from the supply-side.

One such story that is still told is that the business cycle swings are characterised by swings in voluntary unemployment. So a downturn in employment (and a rise in unemployment) arises – allegedly – because workers develop a renewed preference for more leisure and less work and the supply of labour at each real wage level thus moves inwards (that is, workers are now less willing to supply the same hours of labour as before at the going real wage).

So they quit their jobs and head to the beach and relax.

The provision of unemployment benefits – so the story goes – increases the attractiveness of leisure. Why they get to lie on the beach, sipping their champagne and get paid to do it (courtesy of the income support). Who wouldn’t take that option?

Well most nearly everybody wouldn’t take that option but that is an inconvenient reality. Even the sociology of all this is wrong – given the evidence from countless studies that tell us how the unemployed have to endure alienation, shrinking social networks and a collapse in self-esteem.

The upturn in economic activity – so the story goes – is characterised by workers developing a new thirst for work and so the supply curve shifts out again – that is, they are willing to supply more hours of work than before at the same real wage levels. Apparently, they get sick of leisure and gain a new appetite for BMW cars, big watches, and ski-holidays with all the apres activities that accompany them.

And at the empirical level this theory predicts that quits will fall as employment falls.

The simplest fact then, which would give support to this notion of supply-side shifts, is whether the quit rate is, indeed, counter-cyclical – as the theory predicts. That is, does the quit rate rise when the unemployment rate rises or not. Simple enough.

Lester Thurow in his marvellous book from 1983 – Dangerous Currents – knew different and challenged the mainstream view by asking:

… why do quits rise in booms and fall in recessions? If recessions are due to informational mistakes, quits should rise in recessions and fall in booms, just the reverse of what happens in the real world.

The reference to “informational mistakes” is another version of the mainstream supply-side story. The narrative goes that the central bank/treasury can temporarily buy a reduction in unemployment (below what the neo-liberals refer to as the natural rate – another myth) – by inflating the economy with spending.

As economic activity picks up both money wages and prices rise (typical story about too much money chasing too few goods). The trick is that they claim that the rate of increase in money wages is less than the rise in prices and so the real wage falls.

Firms react to the declining real wage by offering more employment – because they know that marginal labour productivity is lower (another myth).

But why do workers agree to supply more labour when the real wage is falling? After all the textbook labour market model tells us that the labour supply curve is upward sloping in terms of the real wage because workers will only supply more labour if the relative price of leisure (which is the real wage) rises.

Another trick to this story then is that the entire supply of labour shifts because workers think that the real wage has risen – they get beguiled by the rise in money wages into forming the view that they are better off per hour than before and so the quit rate falls and employment increases.

Hence, for a time (a short time), the economy can operate at unemployment levels lower than the natural rate.

How long can this go on for? Well, how long does it take for workers to go down to the shops and realise that everything is more expensive now and, in fact, they are worse off than before (because the real wage has fallen)?

Accordingly, once they learn the truth, the labour supply curve shifts back in and workers withdraw their labour en masse (the quit rate rises again) and employment and economic activity falls back to the “natural” level.

The lesson that is hammered hometo students that this all demonstrates how futile policy interventions that aim to lower the unemployment rate are. The only way the “natural” rate can be lowered (if at all) is for policies to be designed with reduce structural impediments in the labour market. What are they? For example, cut the subsidy to leisure (the unemployment benefit). etc.

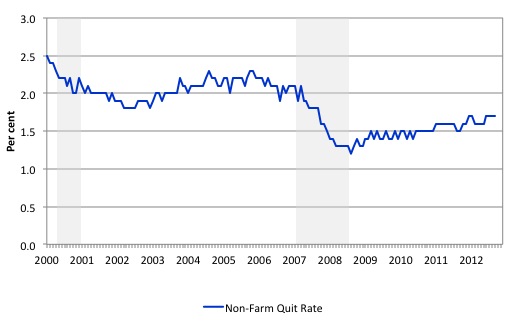

The US Bureau of Labour Market JOLTS database includes estimates of the quit rate. The following graph (for the period January 2000 to November 2013) shows in a compelling way that the quit rate (non-farm quits as a percent of total non-farm employment) behaves in a cyclical fashion as we would expect – that is, it rises when times are good and falls when times are bad.

The grey bars are the NBER recession (peak-to-trough) periods in this sample.

It is clear that when the unemployment rate rises, the quit rate falls. Exactly the opposite to that predicted by the supply-side story which means that their claim that causality runs from unemployment benefits to higher quits to higher unemployment is pure and unadulterated nonsense.

Many studies have demonstrated the phenomenon depicted in the graph.

Workers become very cautious when unemployment starts to rise and postpone any desired or planned job changes and opt for the security of their present job.

When there are more jobs being created and the hiring rate rises, workers then take more risks and the quit rate tends to rise.

Third, there are heaps more people wanting work than there are jobs available.

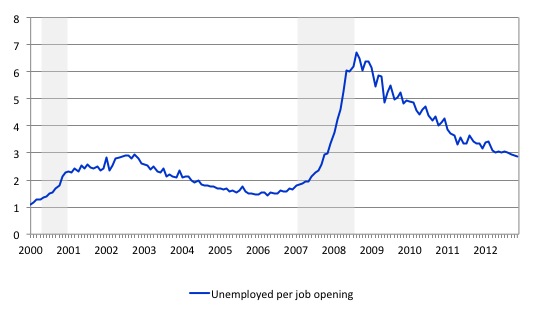

The following graph shows the total number of unemployed per job opening (non-farm and seasonally adjusted) and thus gives a measure of how strong the demand-side of the labour market (job openings) is relative to the number of people seeking work (the unemployed). It is an alternative way of presenting the relationships between unemployment and vacancies.

The shaded-areas denote the NBER recession dates (peak to trough).

In July 2010, the US Bureau of Labor Statistics described the data at that point in this way:

When the recession began in December 2007, there were 1.8 unemployed persons per job opening. The ratio rose to a high of 6.2 unemployed persons per open job, more than twice the highest ratio seen since the JOLTS series began … From the high of 6.2 unemployed persons per job opening in November 2009, the ratio fell to 5.0 in June 2010.

Since 2010, the ratio has been improving steadily as employment growth continues but it still has a long way to go before it reaches the pre-crisis levels where, at its lowest point (March 2007) there were 1.4 unemployed person per job opening.

The ratio has been hovering around 2.9 for some months after persisting in the low 3s for some months before that. It means that the labour market is only very slowly improving with no discernable trend evident for some months. The recovery is definitely not robust.

Labour markets typically behave over the business cycle in an asymmetric manner as can be seen from the graph. The deterioration was sharp and rapid. The recovery is much slower and is all the more slow as the employment growth not only has to absorb new labour force entrants (arising from population growth) but also has to face the huge pool of unemployed that is caused by the recession.

One of the facts I repeat often is that the unemployed cannot search for jobs that are not there! This is exactly what happens when aggregate demand falls and job openings dry up.

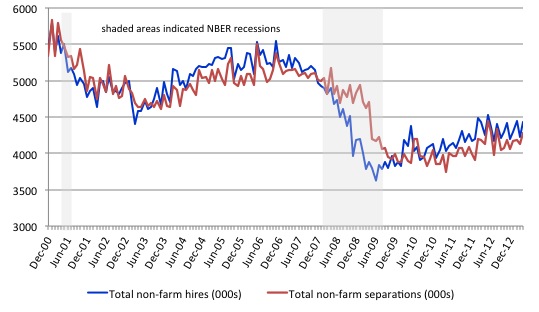

Another way of seeing how the job flows tell us about the direction of change is to compare layoffs with quits. The following graph shows the movements in hires and separations for the US economy as published by the BLS for the period from December 2000 to October 2013.

While labour markets are clearly dynamic in the sense that even in a downturn new jobs are being continually created and destroyed the rates of each dynamic change in a cyclical way. So while there were new jobs being created at the height of the downturn there was a severe shortfall of new jobs emerging as is shown in the graph.

Separations also fall for reasons noted above.

When the labour market is highly constrained by deficient aggregate demand the unemployment queue expands and the ordering of different demographic cohorts within the queue becomes significant. The workers who are more advantaged are able to transit in and out of jobs during a recession more easily than a low-skilled worker who may face prejudice and discrimination from employers.

The most recent data shows that while hiring and separations are showing that the recovery continues the improvement is modest. This is a scale effect. The rates are static.

The US labour market now locked into a situation where the tepid employment growth barely absorbs new entrants and the most disadvantaged workers are being trapped in long-term unemployment.

Accordingly, when there is an overall shortage of jobs, higher-skilled (more educated) workers tend to take jobs that were previously occupied by lower skilled workers. The low-skilled are then forced out into the unemployment queue. So there are two inefficiencies: (a) the skills-based underemployment; and (b) the unemployment.

Bumping down is one of the costs (inefficiencies) of recession – the part of the iceberg that lies below the water!

Please read my blogs – Full employment apparently equals 12.2 per cent labour wastage and More fiscal stimulus needed in the US – for more discussion on this point.

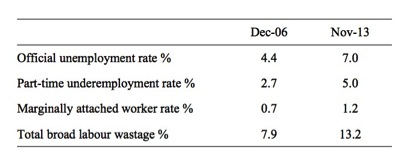

Finally, the next graph shows the BLS series which adds the unemployed, plus all marginally attached workers plus total employed part-time for economic reasons and expresses the numerator as a percent of all civilian labor force plus all marginally attached workers.

The current rate is 13.2 per cent and prior to the crisis it was 8.1 per cent.

The total number of workers employed part-time for economic reasons is a rough indicator (conservative estimate) of underempoyment in the US.

The marginal workers tell us the number of workers who want to and are available to work but who are not actively seeking work in the census period for the relevant month’ survey.

Taken together they represent broad labour wastage in the US and includes all workers who would work if offered a job or more hours of work.

The following Table decomposes the elements of this time series (in rates). You can easily see how far the US is from its pre-crisis state, which in itself was still not very good.

Conclusion

The JOLTS data is very useful because it addresses some of the most simple claims made by the mainstream approach to unemployment. And the evidence is clear. There is no validity in the supply-side case that mass unemployment is somehow something to do with the unemployed being lured into leisure by excessive unemployment benefits or some other reason.

The evidence is consistent and strong – the mass unemployment in the US is the result of a systemic failure in that economy to produce enough jobs, which emerged as aggregate demand collapsed in early 2008.

Since then the economy has been starved of spending because the private sector is unwilling to take risks (and is deleveraging) and the government sector is caught in a conservative web of mindlessness after initially, in the face of a total meltdown in 2008, providing enough fiscal stimulus to kick start the economy.

It was a weak kick and the impacts are fading as the spending cuts widen. The elimination of unemployment benefits will not help this slowdown.

What might be a reasonable policy is this – the presumption of those who negotiated the cutting of benefits is that the unemployed will gain jobs (lets ignore the quality issue for the moment). So the policy might include an elimination of the monthly pay for all those politicians who vote for the cuts if:

1. The labour force shrinks or slows relative to its previous growth rate before the crisis.

2. Employment growth fails to match the pace necessary to absorb all new entrants to the labour force (discouraged or otherwise) and the people who are cut from benefits.

For every month that these conditions occur, the politicians also lose their pay.

Then I suspect not too many would vote for the bill!

That is enough for today!

I live in North Carolina and let me say that most people I meet don’t need empirical evidence to determine whether the unemployed are lazy. It seems that the only evidence they need is whether they have a job. If they have a job, then the unemployed are sucking off of the government teat. If they don’t have a job then, I suppose, they see the other side of the argument. I have used unemployment insurance several times when I worked and I was always thankful for it.

In my opinion you do an admirable job. I really don’t know how you can sift through all of the material that you do and present such a good case for the people. I know it takes a lot of effort and I appreciate not only you but Randell Wray, Warren Mosler, Tom Hickey and all of the others who teach MMT.

Dear Bill

Experience indicates that many people do indeed prefer leisure to employment, but only if they can enjoy leisure with a sufficiently high income. To mention just 2 examples. I know a French teacher who was about 40 when she received a substantial inheritance. She immediately quit her job and never worked again. I also know a guy who owns a big building which he rents to a manufacturer for 15,000 per month. He never works, but plays golf in Canada in the summer and in Florida in the winter.

If you have an awful job, that is, a job which combines low pay with unpleasant work, then you may prefer to have no job if you can get an income without working that is not much lower than what you can get from your awful job. What conservatives want is to force people to take awful jobs. If you eliminate welfare, abolish the minimum wage and limit unemployment benefits to a short time, then a lot of people will have to take awful jobs, as they do in poorer countries.

Maximizing employment can’t be a progressive policy goal. Progressives should also aim to eliminate awful jobs. Let’s compare 2 situations. In situation A, 100 people have jobs, but 20 of them have awful jobs. In situation B, only 90 of the 100 have jobs, but nobody has an awful job. I would say that situation B is preferable. If the choice is between no job and an awful job, then no job may be better. If you have to choose between working 60 hours a week cutting sugar cane in tropical heat and making 10,000 a year by doing that and making 9,000 a year without working at all, then you may very well prefer the second alternative. To say that any job is better than none is conservative nonsense in my opinion.

Regards. James

Hi James, I think you have explored the “quality issue” Bill decided to ignore here.

In any event that is also a serious issue albeit a separate one. A job which provides a minimum of respectability is part of what the Job Guarantee solution (addressed in bills other blogs) provides – setting the minimum standards not only for wages but also for health, safety and respectability of workers. These minimum standard jobs should be better than “awful”, forcing employers to lift their game to attract labour.

Cheers

Tony

Bill is not saying that a horrible job is better than no job. We need to look at the wider content and context of Bill’s work. Bill is saying that a decent job opportunity will be chosen by most people over the alternative of poverty, alienation, isolation, inactivity and lack of meaning and direction. Implicit in the provision of a decent job are;

(a) a living wage

(b) health & safety standards

(c) implicit recognition of worker and human rights (e.g. no sexual harassment)

(d) ability to balance working life with family and private life.

These implicit requirements must be made explicit and mandatory by labour law delivered by good social democratic government. Capitalists and corporations will never deliver these things freely out of the goodness of their hearts. The phenomenon of philanthropy by the rich is usually grotesque when seen in its full context. Indeed, it is how false consciousness flourishes among the rich. They ignore how their exploitation affects workers and the construction of work (a large proportion of people’s lives). Then they turn around and feel good and noble by dishing out some philanthropy to their favourite cause. Often this is a cause that matches their ideological, social and religious biases and serves to entrench and perpetuatue the inequalities of the status quo.

There is another aspect to this foolishness, which is frequently ignored by those advocating the removal of unemployment benefits. A significant number of those who cannot find suitable employment, and need to survive, will turn to criminal activities. The increase in crime in turn will place pressure on governments (because the wealthy will insist on protecting their property) to invest more public funds on security and policing.

‘Yes,’ said Crass, agreeing with Slyme, ‘an’ thers plenty of ’em wot’s too lazy to work when they can get it. Some of the b–s who go about pleading poverty ‘ave never done a fair day’s work in all their bloody lives. Then thers all this new-fangled machinery,’ continued Crass. ‘That’s wot’s ruinin’ everything. Even in our trade ther’s them machines for trimmin’ wallpaper, an’ now they’ve brought out a paintin’ machine. Ther’s a pump an’ a ‘ose pipe, an’ they reckon two men can do as much with this ‘ere machine as twenty could without it.’

‘Another thing is women,’ said Harlow, ‘there’s thousands of ’em nowadays doin’ work wot oughter be done by men.’

‘In my opinion ther’s too much of this ‘ere eddication, nowadays,’ remarked old Linden. ‘Wot the ‘ell’s the good of eddication to the likes of us?’

‘None whatever,’ said Crass, ‘it just puts foolish idears into people’s ‘eds and makes ’em too lazy to work.’

Robert Tressell. The Ragged Trousered Philanthropists 1910

Tressel’s book should be on every school’s reading list.

Unemployment benefits should be replaced with publicly-funded construction and maintenance projects. This would bring a country closer to JG.

Meanwhile, real wages are flat and life expectancy is falling. Everything is going according to plan!

“Unemployment benefits should be replaced with publicly-funded construction and maintenance projects. This would bring a country closer to JG.”

Are you saying it should be compulsory?

I would argue for a voluntary scheme which could be trialled in some of the areas of very high employment. It wouldn’t cost much to set that up , and I’d be surprised if, and even using the accountancy methods of neo-classicial economics, the benefits weren’t shown to be greater than the costs.

@petermartin2001:

Yes, the jobs should be compulsory. The strong guys can do the heavy tasks while everyone can do light tasks like gardening, cleaning, painting, babysitting, catering, etc. The funds would be raised by increasing the deficit and competent contractors would be invited to give the government proposals.

Before enclosure people could simply live off the commons. That is, before 19th century basically.

But times have changed that is not possible anymore.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Enclosure