I have closely followed the progress of India's - Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee…

More fiscal stimulus needed in the US

Yesterday (July 21, 2010), US Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke presented the – Semiannual Monetary Policy Report to the US Congress – before the Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs, in the US Senate. His assessment was rather negative and the most stark thing he said was that the rate of growth is not sufficient and will not be sufficient in the coming year to start reducing the swollen ranks of the unemployed. So the costs of policy inaction at this stage are already huge but growing by the day. These are deadweight losses that will never be made up again. While the US political system is now so moribund that it appears incapable of producing policy outcomes that will advance public purpose and restore stronger economic growth, the data that is freely available points to the need for a further fiscal stimulus. It is such an obvious strategy that the US government should employ.

The Chairman delivered a gloomy assessment of the state of the US economy. He said:

The economic expansion that began in the middle of last year is proceeding at a moderate pace, supported by stimulative monetary and fiscal policies … the housing market remains weak, with the overhang of vacant or foreclosed houses weighing on home prices and construction. An important drag on household spending is the slow recovery in the labor market and the attendant uncertainty about job prospects. After two years of job losses, private payrolls expanded at … a pace insufficient to reduce the unemployment rate materially. In all likelihood, a significant amount of time will be required to restore the nearly 8-1/2 million jobs that were lost over 2008 and 2009. Moreover, nearly half of the unemployed have been out of work for longer than six months. Long-term unemployment not only imposes exceptional near-term hardships on workers and their families, it also erodes skills and may have long-lasting effects on workers’ employment and earnings prospects.

So the US labour market is now locked into a situation where the tepid employment growth barely absorbs new entrants and the most disadvantaged workers are being trapped in long-term unemployment. In this state, we get what the institutional labour economists (like me) call “bumping down”.

Accordingly, when there is an overall shortage of jobs, higher-skilled (more educated) workers tend to take jobs that were previously occupied by lower skilled workers. The low-skilled are then forced out into the unemployment queue. So there are two inefficiencies: (a) the skills-based underemployment; and (b) the unemployment.

Bumping down is one of the costs of recession – the part of the iceberg that lies below the water! Please read my blog – Full employment apparently equals 12.2 per cent labour wastage – for more discussion on this point.

Bernanke noted that “inflation has remained low” and the major fluctuations in the price level has come from “changes in energy prices” and “underlying inflation has trended down over the past two years”. He said:

The slack in labor and product markets has damped wage and price pressures, and rapid increases in productivity have further reduced producers’ unit labor costs.

So despite all the gold bugs (Austrians) and RATEX-Ricardian Equivalence (Chicago-Harvard types) who this time last year predicted that inflation would go through the ceiling the evidence is to the contrary.

The insights derived from Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) always led us to conclude that there would be deflationary pressure in the US economy given the state of aggregate demand.

Bernanke thinks that the US will experience “subdued inflation over the next several years”. So all the money multiplier/quantity theory arguments look very wan when confronted with the empirical reality. But from an MMT perspective a benign inflation outlook is totally consistent.

It is clear that a supply-side shock (for example, energy prices) could spark price pressures. But there will no demand-side pressures pulling up the price level in the US over the next few years. The build up in bank reserves was never going to be inflationary despite the hysteria we have witnessed over the last year.

I wonder if the gold bugs and others ever really reflect on the strident positions they took early in 2009 and wonder why the world didn’t obey their flawed conceptions. I think I have noted before that I recall a mainstream professor who taught me saying that if the theory doesn’t match the data then the data was obviously wrong. Fair enough, the delusion probably sheltered him from the vicissitudes of life!

Bernanke turned to the outlook to 2012 and indicated that the original projections from the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) have been revised in June. They predicted “continued moderate growth, a gradual decline in the unemployment rate, and subdued inflation over the next several years”. But in the light of current developments, the FOMC is now expecting:

… progress in reducing unemployment … to be somewhat slower than we previously projected, and near-term inflation now looks likely to be a little lower … the risks to growth as weighted to the downside.

This more gloomy assessment reflects their concern for “financial conditions” which are now “less supportive of economic growth”. This recognises that the EMU is now in contraction mode as a result of their ill-conceived fiscal austerity programs.

Bernanke also noted that in the US:

…. many banks continue to have a large volume of troubled loans on their books, and bank lending standards remain tight. With credit demand weak and with banks writing down problem credits, bank loans outstanding have continued to contract. Small businesses, which depend importantly on bank credit, have been particularly hard hit.

So all you gold bugs – the massive build up in bank reserves has nothing to do with increasing the capacity of the commercial banks to lend. Please read the following blogs – Building bank reserves will not expand credit and Building bank reserves is not inflationary – for further discussion.

Bernanke then reiterated how the US Federal Reserve had responded to the financial crisis and resulting recession. But in recognising that the situation

… we also recognize that the economic outlook remains unusually uncertain. We will continue to carefully assess ongoing financial and economic developments, and we remain prepared to take further policy actions as needed to foster a return to full utilization of our nation’s productive potential in a context of price stability.

Which leads me to note that the problem with the policy debate in the US is that policy makers are still looking to monetary policy to save the day.

It is clear that the measures the Federal Reserve took in 2008 and which have been largely maintained restored some stability to the financial system. The emergency liquidity measures to keep the interbank market operating and the swap lines were successful in maintain financial stability. But it is clear they have not stimulated aggregate demand in any coherent way.

The low interest rates might lower the cost of borrowing but investors have to have positive expectations that they will be able to sell the output they produce. Those expectations remain subdued which is why the commercial banks in the US are still not lending very much to businesses.

Consumers are also trying to reduce their debt exposure and the saving ratio has been rising. So there is very little thirst for credit coming from that sector.

What is needed in the US is more direct fiscal intervention. For evidence that the first fiscal stimulus package worked see the blogs – How fiscal policy saved the world and Fiscal policy worked – evidence.

However, those fiscal interventions were too small given the size of the problem. What is now desperately needed is another jobs-rich fiscal stimulus.

Here is some evidence to support that policy suggestion.

The hard evidence

The US Congressional Budget Office (CBO) regularly puts out estimates of the GDP and unemployment gaps as part of their exercise in decomposing the federal budget outcome into cyclical (automatic stabilisers) and structural components. As I note in this blog – Structural deficits and automatic stabilisers – their estimates of the automatic stabilisers are likely to be understated as a result of the estimation technique used by the CBO.

On Page 3 of the CBO document – Measuring the Effects of the Business Cycle on the Federal Budget – we read:

CBO’s estimates of the cyclical component of revenues and outlays depend on the gap between actual and potential GDP. Thus, different estimates of potential GDP will produce different estimates of the size of the cyclically adjusted deficit or surplus. More specifically, the calculations remove the budgetary effects of the economy’s falling below or rising above its potential level of output and the corresponding rate of unemployment.

CBO define Potential GDP as “the level of output that corresponds to a high level of resource … labor and capital … use.

So how do they estimate potential GDP? They explain their methodology in this document.

While the technicalities are not something I will go into in this blog – see my recent book with Joan Muysken – Full Employment abandoned for the mathematical and econometric chapter and verse, suffice to say that they CBO uses the standard mainstream method.

CBO say that they:

They start with “a Solow growth model, with a neoclassical production function at its core, and estimates trends in the components of GDP using a variant of a tried-and-tested relationship known as Okun’s law. According to that relationship, actual output exceeds its potential level when the rate of unemployment is below the “natural” rate of unemployment) Conversely, when the unemployment rate exceeds its natural rate, output falls short of potential. In models based on Okun’s law, the difference between the natural and actual rates of unemployment is the pivotal indicator of what phase of a business cycle the economy is in.

The resulting estimate of Potential GDP is “an estimate of the level of GDP attainable when the economy is operating at a high rate of resource use” and that if “actual output rises above its potential level, then constraints on capacity begin to bind and inflationary pressures build” (and vice versa).

So despite saying that their estimate of Potential GDP is “the level of output that corresponds to a high level of resource … labor and capital … use” what you really need to understand is that it is the level of GDP where the unemployment rate equals some estimated NAIRU.

Intrinsic to the computation is an estimate of the so-called “natural rate of unemployment” or the Non Accelerating Inflation Rate of Unemployment (the dreaded NAIRU). This is the mainstream version of “full employment” but is, in fact, an unemployment rate which is consistent with a stable rate of inflation. Please read my blog – The dreaded NAIRU is still about! – for more discussion on why the NAIRU is a flawed concept that should not be used for policy.

Given the history of estimates of the NAIRU, the “steady-state” unemployment could be as high as 8 per cent or as low as 3 per cent. The former estimate would hardly be considered “”high rate of resource use”. Similarly, underemployment is not factored into these estimates.

The concept of a potential GDP in the CBO parlance is thus not to be taken as a fully employed economy. Rather they use the devious shift in definition in mainstream economics where the the concept of full employment is not constructed as the number of jobs (and working hours) that which satisfy the preferences of the available labour force but rather in terms of the unobservable NAIRU.

Policy makers constrain their economies to achieve this (assumed) cyclically invariant benchmark. The NAIRU is not observed and a range of techniques are used to estimate it. Yet, despite its centrality to policy, the NAIRU evades accurate estimation and the case for its uniqueness and cyclical invariance is weak. Given these vagaries, its use as a policy tool is highly contentious.

CBO say that their estimates of the NAIRU are derived from “historical relationship between the unemployment rate and changes in the rate of inflation”, in other words, a Phillips Curve. Please read my blog – The dreaded NAIRU is still about! – for more discussion on this point.

In my recent book with Joan Muysken – Full Employment abandoned we provide an extensive critique of the NAIRU concept. You can also read an earlier working paper I wrote – The unemployed cannot find jobs that are not there! which documents the problems that are encountered when relying on the rubbery NAIRU concept for policy advice.

The point is that the estimates the CBO derive are flawed and will typically understate the degree of slack in the economy. With those caveats in mind I had a look at the relationship between the output gap, the unemployment gap and the annual inflation rate in the US to see what room there was for fiscal expansion.

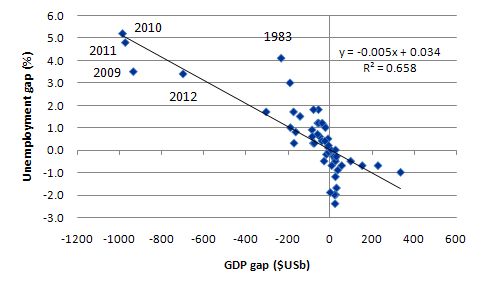

The following graph is taken from the CBO data which they publish regularly. It shows their estimate of the GDP (output) gap ($US billions) on the horizontal axis and the unemployment gap (%) on the vertical axis. The regression (black line) is a simple linear model with a fairly high R-squared (which measures goodness of fit of the relationship). The 2010-2012 observations are CBO estimates.

What we conclude fairly clearly from this graph is that there is a close correspondence between departures from full capacity and rising unemployment. So if you want to reduce unemployment a reliable policy target would be closing the GDP gap.

What the CBO estimates are showing is that the US economy will be largely stagnant over the next few years. Austerity programs – fiscal consolidation – whatever neo-liberal buzz word/expression you like – will only increase the GDP gap and make matters worse. It is simply the wrong policy to be pursuing if you want to reduce unemployment, which is the largest on-going cost of any recession.

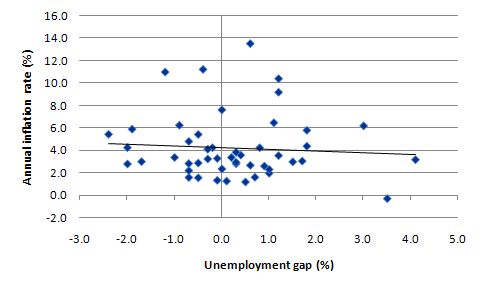

The next graphs are my anti-NAIRU charts. The first is a conventional Phillips curve which plots the unemployment gap (%) on the horizontal axis and the annual US inflation rate (%) on the vertical axis. You can see that there is virtually no coherent relationship revealed. So it doesn’t look like there is a very strong trade-off between unemployment and inflation in the US economy.

I conclude from this (and other more formal statistical and econometric work that I have done recently) that pushing unemployment rate down via a closing of the GDP gap will not be lead to higher inflation.

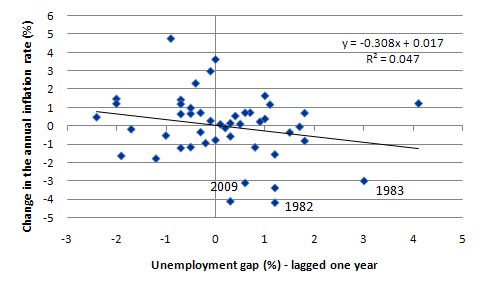

But what about the impact of the unemployment gap on the change in inflation? The NAIRU is the “Non-Accelerating Inflation Rate of Unemployment” so we need to consider the impact of closing the unemployment gap on the percentage point change in the inflation rate. Further, it is unlikely this relationship will be contemporaneous (see CBO methodology paper for more on this). So it is more likely that if there is any impact on the acceleration of inflation it will come from the lagged unemployment gap (by one year).

The next graph shows this relationship and as you can see there is very little evidence at all to support the notion that a negative unemployment gap (that is, the economy operating above what the CBO call full employment) would lead to a rapid increase in the inflation rate. A NAIRU-world would deliver a well-defined negative relationship (sloping downwards from left to right).

Further, the evidence supports our contention that a deflationary strategy of the sort the RATEX/Monetarists would support (now including the Austerians) would be very costly in terms of the real economy given how flat the trade-off is. I qualify that by saying that the relationship is not well specified statistically and more econometric work would be needed to really nail it down.

US economy is now in danger of entering a deflationary phase and if fiscal policy is targetted at closing the unemployment gap (which in the CBO terminology would mean the unemployment rate = their estimate of the NAIRU) then there is very little to fear in terms of introducing significant upward pressure on the inflation rate as a result of the excess demand in the US labour market.

So what should the US government do?

First best US policy option – introduce a Job Guarantee!

In my view, the first thing the US government should do now is to introduce a Job Guarantee. Please read my earlier blog When is a job guarantee a Job Guarantee – where I outline the concept of employment buffers in some detail. That blog addresses many of the concerns that people have about relying on fiscal policy as a counter-stabilisation policy tool.

The Job Guarantee requires that the government provide an unconditional and universal job offer (at the minimum wage) to anyone who wants to work. The job offer never runs out and all the person needs to do is turn up at some allotted location on any particular day to start work. These features make the policy an ideal way to ensure maximum employment benefit is achieved per dollar of stimulus.

First, the the Job Guarantee functions as an automatic stabiliser rather than as a discretionary program. It builds further endogeneity into the budget balance. When the economy turns down, the Job Guarantee pool of workers will rise as displaced workers elect to take the guarantee. When the economy starts to improve again, the private sector merely has to offer a wage (or conditions) better than the JG wage and the JG pool will decline again.

Second, if the planning process is deficient (and it should improve under a Job Guarantee) then the stimulus is spent from day one because the act of turning up at some “JG depot” puts the worker on the payroll and their pay starts from then, irrespective of whether the government has a job ready. This puts political pressure on the government to plan ahead and have an inventory of jobs available that can be offered immediately to workers as they sign on.

For more analysis of this issue you might like to read our report (from a 3-year study) – Creating effective local labour markets: a new framework for regional employment policy. It outlines in considerable detail how job design and project planning can avoid workers sitting idle and also the problem of jobs not being completed if the private sector improves and the Job Guarantee workers are bid away from the pool. Before you make any negative comments please read that Report – we have spent years thinking through all the obvious issues.

Third, the Job Guarantee maintains what I call “loose” full employment. The jobs would be designed to be inclusive for the most disadvantaged workers (who typically bear the brunt of economic downturns). So some displaced workers with higher levels of skills may seek some income security in Job Guarantee employment for the some time. Their skill levels will be above that consistent with the minimum wage (according to the way we consider the productivity-wage nexus – although I note that this is largely inconsistent when applied to executives, IMF officials and their ilk).

The point is that the Job Guarantee is not a universal panacea. It is a safety net employment capacity that provides a nominal anchor for the macroeconomy via the fact that the government would never be competing for resources with the private sector. The private sector can bid the workers away any time they want to pay above the minimum wage (and provide reasonable working conditions). If there are inflation pressures, tighter policy settings would redistribute workers from the inflating private sector into the fixed price Job Guarantee pool and stabilise prices. That is how buffer stocks work.

The value of this approach is that the government knows exactly how much stimulus is required to achieve this “loose” full employment on a daily basis. The tap turns off when the last worker walks in the door on any day looking for a job. This provides daily feedback to the fiscal system and overcomes the uncertainty of timing and guessing the size of the stimulus.

Once the economy is at full employment – in this sense – the government can then design other stimulus measures that it deems to be politically sustainable (and which hopefully add social value) to create employment and activity elsewhere. But it always knows that if the nominal demand levels come up against the real capacity of the economy then employment will just be redistributed if policy tightening is required rather than unemployment being created.

So the concept of employment guarantees reveals that economists who think that stimulus packages cannot have an immediate employment effect are not thinking clearly enough. The government can always buy labour that no-one else wants. Should that labour not choose the job offer – fine. But the fact remains that a sovereign government faces no financial constraints in achieving continuous full employment without endangering price stability. There can be no inflationary impulses coming from buying labour at a fixed price that no-one else wants.

The problem with the current approach to fiscal policy is political. The governments think that large deficits are bad so they spend on a quantity rule – that is, allocate $x billiion – which they think is politically acceptable. It may not bear any relation to what is required to address the existing spending gap.

The better basis for the conduct of fiscal policy which is exemplified in the provision of employment guarantees is to spend on a price rule. That is, fix the price and buy whatever is available at that price. After all, the budget deficit is endogenous and has to be whatever it takes to get full employment.

If the business community or anyone else thinks the deficit is “too high” or that there are “too many” workers in the Job Guarantee pool – then there is a simple remedy that is available to them – they can just lift their private spending (for example, invest more in productive capacity). Then the budget deficit will shrink and the Job Guarantee pool will decline. If they hated the Job Guarantee so much they could simply employ all the workers in the pool!

But the Job Guarantee creates a safety net that is always there to cope with private sector spending fluctuations (driven in part by varying saving desires). In that sense, it is infinitely superior to using unemployment as the buffer stock to cope with the flux and uncertainty of private spending. It is almost unbelievable to me that we tolerate governments sitting idly by watching millions of people around the world being forced into unemployment for want of some funding that the government can always provide.

The Job Guarantee would also overcomes many of the problems that bedevil the “politicised” conduct of fiscal policy. Enough for today.

Conclusion

The data provides the strongest case there is for a further fiscal expansion in the US. The output gaps are still huge and they directly cause the unemployment gaps. Closing the output and unemployment gaps will not be inflationary.

The best thing the US government can do now is to directly intervene into the jobs market and provide a job for anyone who wants one. This “loose” full employment model is within the financial capacity of the US government and would provide a significant lift to economic growth.

That is enough for today!

Bill, I have to say you are very persistent! But is anyone that counts listening? Hearing Obama talk with Cameron about “debt-to-GDP ratios” I think sadly not 🙁

It sounds like you are 100% certain a job guarantee would work. If only a major politician in a major currency-issuing nation was too!

Bill, given the US Governments and Congresses past and present abilities to undertake meaningful programmes that haven’t been hijacked and influenced by lobbyists and vested interest groups let alone sheer incompetence, your great idea will be lost on the monumental stupidity that dominates the US.

Job Guarantee: won’t happen. Why? Here’s Michael Kalecki’s explanation (I’ve added the two words in the bracket):

More fiscal stimulus is needed. Agreed! Insofar I’m a little bit astonished that some proponents of MMT Paul Davidson, James Galbraith and and Lord Skidelsky (not sure about his stance) declined to sign a letter initiated by Sir Harold Evans, supported by Joseph Stiglitz, … asking for such stimulus to “Get America Back To Work”.

They declined to sign the manifesto because of one sentence “We recognize the necessity of a program to cut the mid-and long-term federal deficit.. ” Certainly this sentence is rubbish. So what? The main goal is to get a stimulus NOW. I think it’s not very helpful to undermine this effort and withhold intellectual support just for the purpose of the purity of the message.

This won’t make the deficit hawks go away. And this sentence is so vague, that it carries no intellectual weight. If someone in 2 years wants to nail down JG on this sentence he can say: “Sure, I’m thinking about shrinking the defense budget.” or “Sure, let’s introduce a mild VAT in the US.” Anyway this is a fight they can have later. In the meantime common folks will learn that the sky is not falling because of deficits.

Stephan: where did Kalecki say that?

I’m inclined to agree with Davidson, Galbraith and Skidelsky on this one. They could remove the offending sentence, since retaining it won’t make the deficit terrorists go away, and doesn’t affect the main goal of getting the stimulus now. Leaving the sentence in leaves you wide open to being mopped up by the deficit terrorists. It’s not a question of ‘purity’; it’s more a question of thinking ‘strategically’. Why can’t Sir Harold Evans and Co. oblige?

Stephen:

Signing a manifesto containing statements antithetical to your principles isn’t much of a statement. You don’t get your main goals by showing you are willing to throw away your core beliefs so easily.

The primary purpose of a manifesto is to gain popular support by having respected individuals put their name behind a shared statement. The last thing we need is the public to hear some qualifications about “well, deficits need to be cut, but …”.

What we need in the US is a statement along the lines of:

“Without federal aid to the States to assist in closing the budget gap caused by the financial crisis, our economic condition will worsen, unemployment will rise, aggregate demand will fall and we will stay in this deep recession for a very long time. Government needs to start aggressively investing to make up for the deep decline in private spending. The focus on deficits is misplaced – the US has had much larger debt to GDP ratios in the past and each time they declined once private economic activity was reactivated by government spending. It is political cowardice and sheer stupidity to avoid the facts and score short-term points at the expense of the unemployed.”

@Brianovitch

Michael Kalecki “Political Aspects of Full Employment” (remove_this_http://gesd.free.fr/kalecki43.pdf)

OK in regard to the letter I respect your objections. I’m somehow more pragmatic on the issue. Most people won’t even remember about this sentence in some months. Second if a stimulus is enacted and does what it is designed for to “Get America Back To Work” the deficit will shrink anyway. Thus the program to cut the mid-and long-term federal deficit is the stimulus. So where’s the problem?

Bill ~ Unrelated, but this from Mankiw (2010-7-10):

“Some research suggests that the long-term unemployed put less downward pressure on inflation. If that is indeed the case, then the increase in long-term unemployment may mean that we will see less deflationary pressure than we might have expected from the high rate of unemployment.” ( http://gregmankiw.blogspot.com/2010/07/median-duration-of-unemployment.html )

Mankiw seems (to me) to be suggesting that a generic decrease in an individual’s demand by a fixed amount has a different effect on aggregate demand depending upon how long that person has been unemployed. Am I misreading this? Is Mankiw actually suggesting that the unemployed just sort disappear (economically) if you just hang them out to dry for long enough?

And if this were true for unemployment, wouldn’t this imply that a similar variability might also be applicable to ANY source of demand? Wouldn’t this then imply that:

Ʃ Individual Demands ≠ Aggregate Demand,

and wouldn’t that make ALL calculations of aggregate demand purely whimsical and therefor useless?

What am I getting wrong here?

Bill,

You often reference the origin of the current crisis is productivity gains did not go into the pockets of consumers. So to sell the ouput consumers went into debt. How does a JG solve this problem? I see numerous benefits of a JG but the original problem is not solved. I still see productivity gains flowing to the top resulting in more workers joining the JG.

A JG and govt spending may have been the answer to the great depression, but times are different now. Middle class tax rates were much lower back then. Today we have a 15% tax for SS and Medicare and marginal tax rates for the middle class are above 20%. That’s taking a ton of demand off the table.

The middle class here in the U.S. has had enough. While I am a firm believer in MMT, you will never win over the majority here preaching a JG. Most will just say “more govt jobs will increase my taxes” and turn you off. But if you start with “MMT says your payroll tax can be eliminated while maintaining all SS benefits because…” you will turn more ears your way.

Stephan: Many thanks for the Kalecki reference.

As for Sir Harold Evan’s letter, you may well be right. But it’s up to everyone to exercise their own sense of prudence in such a matter.

From the Semiannual link:

“Most FOMC participants expect real GDP growth of 3 to 3-1/2 percent in 2010, and roughly 3-1/2 to 4-1/2 percent in 2011 and 2012.”

It seems to me some people are living in fantasyland.

I thought I saw the latest projections were 2.7% actual Q1.

Estimated:

Q2 – 2.0% to 2.5%

Q3 – under 2%

Q4 – under 2%

Maybe from Roubini?

Dear MarkG (at 2010/07/23 at 2:30)

Note I said:

There are lots of other things that the US government should also do including major changes to the financial sector; major changes to the way the national product is distributed; major reform of the health system; etc. But in a fiat currency system you need a nominal anchor. You can either choose buffer stocks based on unemployment or employment. I choose the latter.

As part of my desire for people to understand the options within the monetary system we live with I will always advocate a JG because it is part of the overall macro stability framework that MMT provides insights into. I don’t care if an uneducated public is not yet ready to accept that. If I don’t say it regularly who will and how will we ever change our views? I write to influence long-term changes in thinking not today’s policy mash-up, although it would be lovely to influence that too.

best wishes

bill

markg: “While I am a firm believer in MMT, you will never win over the majority here preaching a JG. Most will just say “more govt jobs will increase my taxes” and turn you off.”

In the US I think that one way to sell JG is as workfare. If you are unemployed for longer than a few months, then you have to work for your gov’t check. Or if you prefer, or are not eligible for unemployment, you have a guaranteed job. There is no shortage of public works.

bill said: “There are lots of other things that the US government should also do including major changes to the financial sector; major changes to the way the national product is distributed; major reform of the health system; etc. But in a fiat currency system you need a nominal anchor. You can either choose buffer stocks based on unemployment or employment. I choose the latter.”

What about “buffering” retirement?

If the lower and middle class (the entity experiencing negative real earnings growth) refused to go into debt to the rich, what would happen if the national product was not distributed evenly?

If productivity gains were distributed evenly, could the retirement age go down?

Prof. Bill,

I used to be where markg is but am now seeing (to me) that the JG is the most important part of MMT, must have it. Great post wrt the JG.

Resp,

PS wrt the Emoticon: You’re always ‘loved’ !

bill said: “I don’t care if an uneducated public is not yet ready to accept that. If I don’t say it regularly who will and how will we ever change our views? I write to influence long-term changes in thinking not today’s policy mash-up, although it would be lovely to influence that too.”

I would suggest explaining all the possibilities.

If productivity and/or cheap labor produce price deflation, should it:

1) be allowed to happen

2) be price inflated with private debt

3) be price inflated with gov’t debt

4) be price inflated with currency

Have I missed any?

Benedict re Mankiw and the inflation bogeyman,

If that’s Mankiw underlying assumption, it’s chilling. In the long term the unemployed don’t just ‘disappear economically’; unfortunately they tend to end up in an early grave http://mja.com.au/public/issues/feb16/mathers/mathers.html. Not sure how dying is inflationary, though. A funeral home led recovery?

Bill,

In terms of a JG scheme, I’ve yet to hear you comment on the NREGA scheme in India, devised by the current UAP government after recomendations from Jean Dreze of Uni of Delhi.

The main criticisms about if tend to be cost blow outs related to corruption, but i can see ample transpacrency measures pure in place in a country such as Australia to virtually eliminate this.

Have you examined this scheme as it does appear to be a Jobs Guarantee scheme, albeit with some limitations put in place (100 days per year for those who aren’t aware of it).

OK, I do see a post from last year, https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=6143

I’ll read it before I’ll ask any more questions.