It is true that all big cities have areas of poverty that is visible from…

Poverty rates rise in the UK as low income households bear austerity burden

Over the weekend, I was reading the new report from the British Social Mobility and Child Poverty Commission – State of the Nation 2013: social mobility and child poverty in Great Britain – which has just been presented to the British Parliament (October, 2013). The conclusions from the Report are not good. They find that the “falls in poverty seen over the last 15 years may be be reversing” and that “(a)bsolute poverty is rising”. The UK will likely miss its “2020 target to end child poverty”. The other shocking statistic is that poverty rates among those who work are rising and “(t)wo in three poor children are now in families where someone works”. There are now “5 million adults and children in working poor households” in Britain. This puts the skiver/bludger/welfare criminal narrative that the neo-liberals in Britain have been running into a different light. It cannot be said that workers are skivers – they get up in the morning (or sometime) and sacrifice the best part of their lives working for some capitalist or another. They are increasingly getting paid such that they cannot live above the poverty line. That is a failed state if ever there was one.

We learn that the:

The Social Mobility and Child Poverty Commission is an advisory non- departmental public body established under the Child Poverty Act 2010 (as amended by the Welfare Reform Act 2012) with a remit to monitor the progress of the Government and others on child poverty and social mobility.

The Commission is chaired by a Labour MP (Milburn) and co-chaired by a Conservative MP (Shephard).

It seems from reading their Report that they have taken it on themselves to also make macroeconomic assessments of the financial constraints facing the UK government such that it claims that any future government in the UK will face:

… a major fiscal challenge in the medium term … we risk spending more as a country than we are earning. Austerity is likely to be with us beyond the short term. Something will have to give. In future, governments will have to accept that hard choices will need to be made about where they place their bets.

All of which is claptrap when applied to the UK and reinforces the notion that there will be nothing serious done about the increasing poverty in the UK while this ideological straitjacket chokes all understanding of what are the real choices and opportunities.

However, I was interested in their analysis of the distributional impacts of the fiscal consolidation over the last few years.

Overall income distribution in the UK

Overall income inequality has risen in the UK quite dramatically since the surge in Thatcher’s regime.

I usually talk about movements in the wage share which refers to the so-called functional distribution of income, which divides national income up by what economists call the broad claimants on production – the so-called “factors of production” – labour, capital, and rent. Other classifications also include government given it stakes a claim on production when it taxes and provides subsidies (a negative claim).

The other main classification system used to analyse the distribution of income is what is called the size distribution of income or personal income distribution, which focuses on distribution of income across households or individuals. Often the data is expressed in percentiles (each 1 per cent from bottom to top), deciles (ten groups each representing 10 per cent of the total income), quintiles (five groups each representing 20 per cent of the total income) or quartiles (self-explanatory).

Various summary measures are used to demonstrate the income inequality. For example, the share of the top 10 per cent to the bottom 10 per cent.

The Gini coefficient is another summary measure used in this type of analysis. The ABS publication – Household Income and Income Distribution, Australia, 2009-10 – defines the Gini coefficient as:

… a single statistic that lies between 0 and 1 and is a summary indicator of the degree of inequality, with values closer to 0 representing a lesser degree of inequality, and values closer to 1 representing greater inequality.

If you want to extend your knowledge further then this academic article (from 1954) – Functional and Size Distributions of Income and Their Meaning – is a good starting point for understanding the two concepts in more detail, although you need a JSTOR library subscription to access it.

[Full Reference: G. Garvy (1954) ‘Functional and Size Distributions of Income and Their Meaning’, The American Economic Review, 44(2), Papers and Proceedings of the Sixty-sixth Annual Meeting of the American Economic Association (May, 1954), 236-253]

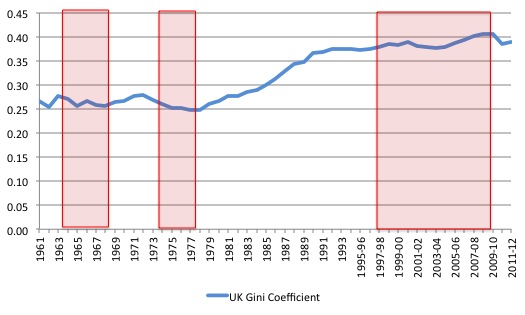

The following graph plots the Gini Coefficient for the UK from 1961 to the 2011-12 fiscal year. The red shaded areas indicate periods when British Labour was in power. The plot closely mimics what you would see if we plotted the so-called 90/10 ratio – which considers the income received by the 90th percentile of the income distribution as a ratio of the income received by the 10th percentile. It has risen from around 3.2 in 1961 to 5.2 in 2011-12 (and is rising).

Observations from the graph include:

1. When British Labour is in power income inequality does not rise except when it became “New Labour”, which was code for neo-liberal in the period from 2003-04 until their demise in 2010.

2. Income inequality almost always rises under the Conservatives.

3. Income inequality shifted dramatically upwards under the Thatcher government and the rate of increase moderated under Major.

4. Income inequality is on the rise again under Cameron.

5. By comparison, Australia’s value is around 0.34 and this has risen from 0.30 over the last 20 years – but still much more egalitarian than the UK. The Gini for the US is up around 0.48, which means the UK is doing its best to mimic the inequality in that nation.

Child Poverty rates on the rise again

Overall poverty rates in Britain are now rising. Between 2010-11 and 2011-12 and extra million British people entered poverty (BHC) and 900,000 (AHC).

While the traditional sources of poverty have fallen (old-age and retirement) the IFS study (published June 2013) –

Living Standards, Poverty and Inequality in the UK: 2013 – documents are marked rise in the working poor:

Rising poverty among working-age adults without children partly reflects substantial increases in the number living in workless families and a decline in the relative value of out-of-work benefits. More importantly, poverty among those living in families containing at least one worker has increased. During the period 1978-1980 to 1996-97, this reflected an increase in hourly and weekly earnings inequality. Post 1996-97, it reflects the fact that any earnings growth was generally weak for this group right across the income distribution.

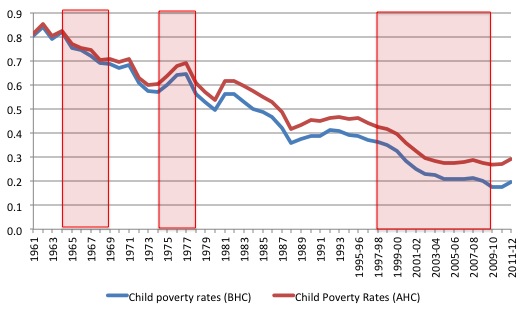

The following graph shows child poverty rates in the UK from 1961 to 2011-12 using the benchmark of 60 per cent of net equivalised household income as at 2010/11.

The red shading is as before. BHC refers to before housing costs are taken into account, AHC after housing costs are deducted from income.

The Cameron government is overseeing a rise in child poverty rates.

Fiscal consolidation and Poverty

For me the most interesting aspect of the report was its analysis of the distributional impacts of the fiscal austerity being imposed by the current national government in the UK.

The Report notes that nations with rising poverty rates incur all sorts of negative consequences. Nations with rising poverty rates endure declining educational attainment and personal development.

The single most evocative (and dammning) sentence in the Report is:

Poorer children fall behind in development before the age of 3, and never catch up again.

That is, a life sentence of harship is imposed on babies who didn’t ask to be born.

The Report also nots that:

Britain cannot afford to waste talent and potential that could make a major contribution to growing a sustainable economy.

What is often lost on the neo-liberals is that the single most significant source of waste and inefficiency is mass unemployment and the poverty that it produces.

In an era where, every day, some policymaker or another warns us about the dangers of the ageing society it is amazing how disconnected their narrative is when their next statement urges us to get tough on the unemployed (which only makes them poorer and less likely to acquire the skills necessary to ensure a high productivity future for all of us).

It is even more stunning when all of the research data tells us about the massive future costs that society will bear from forcing higher numbers of children to grow up in poverty-stricken households.

Any forward-looking government with an eye to the evidence would do everything they could to ensure that no child was born into or grew up in an impoverished household.

But that is not what government obsessed with fiscal austerity do – they make poverty and child poverty worse and we will all pay for it in the years to come – the costs being borne disproportionately, though, by those who have to endure the poverty.

The Report outlines “five main reasons for making child poverty and social mobility national priorities for action”.

1. “Fairness case” – moral argument.

2. “efficiency case” – waste and cost-savings relating to avoiding problems that poverty brings.

3. “economic case” – increased demand on welfare system etc.

4. “growth case” – economies with rising inequality do not grow as consistently as those with reduced inequality. Even the IMF believes that now.

5. “business case” – reduced poverty lowers the cost of recruitment etc because social mobility is higher.

However, the Report claims that these are “tough times for making progress on improving social mobility and reducing child poverty”.

To which I ask why?

And the Report says there are four main challenges:

1. The “economic challenge” – as a result of the deep recession and slow recovery. Clearly, this is not a challenge but a failure. The deep recession and slow recovery Could have been avoided, without doubt, if the government had not become obsessed with austerity.

The British government has all the capacity needs to ensure that aggregate demand remains strong enough to keep all those who wish to work in employment at a wage that is above the poverty line. That is unquestionable and any deviation from that position in the real world is a policy choice.

It could have substantially reduced poverty rates over the last three years if it so desired. There is no question about that.

The British government chose to allow its economy to suffer a debilitating recession with a very weak recovery. It is therefore responsible for the negative consequences, which include the rising poverty and child poverty rates.

2. The “fiscal challenge”:

.. is that there is less money to support the incomes of low-wage families and fund services that level the playing field on life chances. All the main parties are committed to fiscal consolidation (the debate has been about timing and structure), so this is about how, and not whether, difficult choices are made. Austerity is not ending any time soon, regardless of the result of the next Election … Crucially this is not just a short-term constraint. An ageing society means we face a long-term dilemma of funding working-age social objectives when there are fewer workers per retiree.

The claim that there is “less money to support the incomes of low-wage families and fun services that level the playing field” is an unmitigated lie.

The honest statement is that the government is choosing to make less money available. The British government, as the currency-issuer of the pound, has infinite minus a penny pounds available to spend at any time.

Further, as regular readers will appreciate the ageing society claim is without application to a sovereign nation. The real challenge facing societies with increasing dependency ratios is whether there will be enough real goods and services available in the future to ensure real material living standards are maintained and increased.

Above all, that is a productivity challenge and nations that undermine their education systems and hold increasing proportions of the population in poverty and joblessness are doing exactly the opposite to meet that challenge and will pay the price as the dependency ratios continue to rise.

Please read my blog – Ageing, Social Security, and the Intergenerational Debate – Part 3 – and the earlier parts (linked in Part 3) – for more discussion on this point.

It is sad that this group, which recognises that the “fiscal consolidation to be regressive, with the lowest-earning fifth of households making a larger contribution than any other group except those in the top 20 per cent, both as a proportion of their incomes and in absolute terms” is prepared to roll over and play doggo on the fiscal lie.

3. The “earnings challenge” – recognises that “employment and earnings are the key drivers of child poverty” and that real wages are in decline – “real median weekly earnings have fallen by 10.2 per cent since 2009 and are now lower than in 1997, putting a tight squeeze on standards of living”.

4. The “cost of living challenge” – real wage cuts due to rising costs. Remarkably, “(h)ousing costs, water, electricity and gas take up nearly 60 per cent of total income for the poorest tenth compared with less than 30 per cent of that of the richest 10 per cent.”

What has been the impact of the fiscal consolidation on lower income groups?

The Report notes that the British government has choices have included:

– Accelerating the speed of fiscal consolidation relative to the plans of the previous administration, based on its judgement that this was essential to secure market confidence and avoid fiscal crisis.

– Shifting the balance of fiscal consolidation away from tax rises and towards spending cuts, in line with its assessment of the international evidence.

– Making significant discretionary cuts to social security expenditure to reduce the pressure on public services, focusing on reducing benefit and tax credit entitlements for children and working-age adults while increasing the generosity of the state pension and protecting most other benefits for pensioners.

– Shifting the pattern of taxation, for example by increasing the income tax personal allowance by one-third in real terms and raising the rate of VAT from 17.5 per cent to 20 per cent.

They then consider the “short-term” consequences of these decisions.

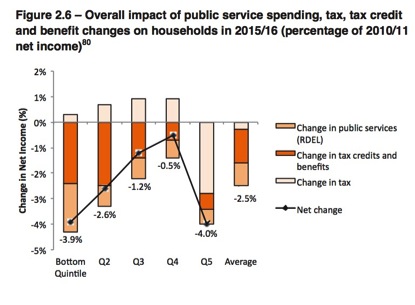

Their Figure 2.6 (reproduced next) summarises the “overall impact” in terms of percentage changes in net income (against the 2010-11 benchmark).

The results show that the “the highest earning 20 per cent of households making the greatest contribution to reducing the deficit, both in absolute terms and also as a proportion of their incomes”.

However, once you take the highest earners out of the picture, the impacts of the fiscal consolidation are disproportionately being borne by families in the lowest quintile of the income distribution.

They say that:

… those at the bottom making a larger contribution than any other group except those in the top 20 per cent, both as a proportion of their incomes and in absolute terms.

The results also show that the fiscal consolidation damages the “the young more than the old, and those with children more than those without”.

Which is exactly the opposite to what you might want if you are worried about the ageing society.

The overall conclusion is that:

… the Commission concludes that the process by which fiscal consolidation has been implemented is placing an unfair burden on the poorest households – including those in low-paid work …

The Report considers this situation is not “sustainable for the future” and urges the government to:

1. Increase the mininimum wage.

2. Eliminate youth unemployment.

3. Increase apprenticeship opportunities.

4. Promote a rise in real wages generally.

5. Stop targetting fiscal consolidation at the lowest quintile.

All these are admirable suggestions and could be augmented by the introduction of a Job Guarantee where the British government could unconditionally offer a public sector job to anyone who wanted to work for a minimum wage that was above the poverty line and allowed people to be socially included.

Conclusion

As time passes there will be more opportunities to analyse the consequences of fiscal austerity. At present, my research group are examining the spatial consequences in Australia of the fiscal contraction. More about that later.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2013 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

The “earnings challenge” (“real median weekly earnings have fallen by 10.2 per cent since 2009 and are now lower than in 1997”) is ironic, given that poverty is mainly defined in the report (and elsewhere) as relative to the median wage. In this environment, it should be easier, not harder, to eliminate “poverty” – just make sure that government support of the lowest income groups is maintained at current levels in real terms, and the maths will do the rest. The fact that child poverty has increased since 2009 is a clear indication that government cutbacks have targetted the poor.

Prof Mitchell,

Nice analysis, but I have some niggling problems.

1. Increase the minimum wage. Why is this often a proposal? I can understand the need for ALL citizens to have a basic, living (not subsistence) income, so why emphasize the waged-labour sector?

2. Eliminate youth unemployment. This is pure political waffle – no matter which side of the political mouth it emanates from. How can any government affect employments – in any sector? Surely this must be the ‘responsibility’ of the private, productive and service, sectors?

3. Increase apprenticeship opportunities. Ditto as for 2. How?????

4. Promote a rise in real wages generally. Yep, I’ll buy this one, but again, how?

5. Stop targeting fiscal consolidation at the lowest quintile. Yes indeed. Except this quintile may not be enthusiastic voters. Politicians only care about folk who vote regularly – and even more so if these voters are ‘contributors’.

Has anyone done any work on a Theory of Income? And. Any WoWs [words of wisdom] on the negative impact of those Negative Incentives. You know, the one what that little rich brat, Oliver Twist, was demanding! The rich ‘looking’ for more!

Brian Woods

Brian, with all due respect, Roosevelt accomplished your 2 in the 1930s. The government hired all sorts of people for all sorts of projects, including writers and artists. He was encouraged in this by his wife Eleanor and Harry Hopkins, one of the architects of the New Deal. Without them, Roosevelt might not gone as far and done as much as he did. Even with their encouragement, he faltered. And one should never forget the attempted military putsch organized, rather badly, by some of the very rich (a few of whom admired Hitler), which was prompted by Roosevelt’s New Deal for the poor and the less well off.

With respect to a theory of income, Keynes supplied one as have a number of other economists since then.

Again I refer to the reality of the situation – whether the underlying theory is sound or not, policy makers are pursuing an ideal that a surplus is required for economic stability. While we know this to be unsustainable in the long term, I believe the key to turning it around is to focus on the middle and upper class of society.

Governments talk about Austerity measures, but these are generally implemented as punitive measures against individuals already marginalised. There is no substantial electoral penalty to reducing welfare benefits to a relative minority of people, particularly when both sides of politics are colluding on the issue.

Conversely, how to you think the electoral role would react if there was a 10% increase to the top 2 tax brackets? What about reducing the capital gains discount for assets held over one year? Reducing franking credits on dividends? Making trust structures pay tax at a marginal tax rate (the same as an individual) with distributions then being untaxed? I believe that a combination of these measures (there are many more) would make the big end of town feel austerity more, either through reduced revenue from investment activities or (in the event that they pass costs to consumers) through rapidly accumulating inventories and realisation crises.

The true evil of the austerity line is that it is not true austerity, it is a targeted dehumanisation of those with the least ability to lobby against the changes or force a meaningful political change. This can be solved by making the pain felt evenly across society, such that policy makers are forced to abandon the false ideal of surpluses for economic stability.

“I believe that a combination of these measures (there are many more) would make the big end of town feel austerity more,”

If I read the runes correctly, then the MMT approach would suggest that the best method is to tax savings. So ending pension and ISA tax reliefs, issuing a penalty charge for cash and bond holdings on a company balance sheet, increasing corporation tax while at the same time allowing investment spending to be written off as revenue expenditure and possibly even dividend payments.

Plus of course removing any interest paid on Gilts, etc.

These would then be ‘redistributed’ to the lower end of society.

The problem is whether changing these duties would just increase the desire to save.

@ Larry: Thanks for that. Its kinda like, 2013, and we have the Grandmother and Grandfather of all financial busts ringing about our ears. My Q was related to HOW current govs might cope with Youth unemployments (they cannot!). However. Ditto for a Theory of Income – 2013s style. Welfares as we encounter them are a tad different to-day. Think Credit cards, etc., etc. The 1930s economies were hardly demand-driven by the ready availability of credit and they did not have 600 million souls in Chindia whacking out cheapish stuff – and all that entails. Things really are different!

MMT is one of those new-fangled fads – like Hoola-Hoops. Terrific on the pages of comic books. But not so cool when roaming the Outback! Would you take MMT on your Walkabout? NBL! (not bl**dy likely!)

Thanks again for the reply. See you about.

@Neil

One of the key points of MMT is that the private sector always has a net desire to save, and that the shortfall must be made up by government to maintain full utilisation of resources and maximum growth and output in real terms.

My strategy essentially forces the pain of a non-MMT austerity package into the section of society most capable of doing something about it. By reducing the attractiveness of various investments (conceding that targeting cash holding is likely to achieve an overall similar effect) you can directly reduce the ROI for sections of the economy who derive most of their income from investment (as opposed to labor wages or welfare). This will ultimately force a crisis of thrift or realisation (depending on whether the public sector maintains or abandons it’s desire to net save in the face of recessive conditions) and spur calls for a ‘stimulus’ from government.

While the cost of recession is primarily focused on low income earners and welfare recipients, it will ultimately take much longer for a crisis point to be reached – the Howard Government maintained a very long period of surplus by the fortunate willingness of the private sector to net-borrow at the time, though ultimately this led to a realisation crisis and if you look at discounts to inventories – One of the big 4 publishes a fairly regular series on accumulation & discount which indicates that we are still in a realisation crisis now.

Interesting blog.

I read the Commission’s analysis as being explicit that, as every single mainstream political party accepts austerity, agrees on the extent of spending cuts required over the medium-term and is not touting massive tax rises to meet the fiscal pressures (whatever the rights or wrongs of those judgements by the four main parties), it has pragmatically decided to go with that assumption.

Personally think they are on the right track agitating for a shift from corporatist capitalism where the taxpayer subsidises sub-poverty wages to one where employers use some of their exploding profits to pay their staff enough to live on (even if that is for the wrong reasons, based on the assumption that Government spending is currently too high)

Note the political make-up of the Commission as well – it is definitely on the right which makes their cutting critique of the Government on poverty and social mobility all the more surprising

Brian P Woods:How can any government affect employments – in any sector? Surely this must be the ‘responsibility’ of the private, productive and service, sectors?

My Q was related to HOW current govs might cope with Youth unemployments (they cannot!).

Governments can affect employments in any sector (how could it not?) , cope with Youth unemployments very, very, very, very easily. By hiring the youths and the unemployed in any sector. Employment CANNOT be the responsibility of the private sector. In a modern monetary economy, the state’s money is the base money, at the top of the pyramid of money (mangle that metaphor!)). This very fact means that the private sector does not have the power to do stably, fully employ everyone.

You are getting things backwards. MMT is commonsense, robust, intuitive economics, economics that everybody understands. Economics that you can take to the outback. Neoclassical, neoliberal, mainstream, marginalist, commodity theory of money economics is the fragile fad.

As Keynes said:

Our main task, therefore, will be to confirm the reader’s instinct that what seems sensible is sensible, and what seems nonsense is nonsense. We shall try to show him that the conclusion, that if new forms of employment are offered more men will be employed, is as obvious as it sounds and contains no hidden snags; that to set unemployed men to work on useful tasks does what it appears to do, namely, increases the national wealth; and that the notion, that we shall, for intricate reasons, ruin ourselves financially if we use this means to increase our well-being, is what it looks like — a bogy.

@ Some Guy: Thanks for your reply. I’m in Ireland, so it takes at least 10 hours for the e-mails to arrive!!!

My query is basically about the manner in which tax revenues should be spent. Also, when a state borrows to fund day-to-day activities (we borrow 50 mill euro each week here in Ireland) that imposes a debt burden on taxpayers,and their dependents, and ensures that future incomes (national and personal) will be diminished by debt repayments. I’m assuming that national debt is never zeroed – we never have a balanced budget, and we simply roll-over debt as it comes due. The whole mess is predicated upon the economic paradigm of Permagrowth. The real G*P growth (actual output – increase in debts) must be able to meet the debt burden – or else! Permagrowth appears to have stalled.

Another point is that I do not believe govs have any business in ‘creating’ jobs – other that public service ones. That is the job of the private sectors – in aggregate. The issue being raised – given the current crisis in Europe, is how are employments to be maintained, in the face of falling demand? – if what the gov has to do to stimulate demand is to borrow funds and somehow or other ‘spend’ these monies into the economy. This is a bad joke. It cannot work no matter what anyone has said, or is saying. The math says No! – and that’s it. Maybe I’m missing something here, and if so, I would really welcome some enlightenment on the matter.

Now of course some folk will say – you have to ‘incentivize’ private sectors both create new employment sources and increase the number of employees in existing enterprizes. Why do we have to ‘incentivize’? Are the private sectors not populated by adults who are eager and willing – or are they actually modern-day Oliver Twists – with their begging bowls outstretched and pleading, “Please minister, give us some more!” Now this sounds awfully like the pleas of welfare recipients – and we take a very dim view of this latter group. Yes? If modern industry and commerce cannot provide for increases out of their own surpluses – then something is badly wrong. This pre-supposes that the government will not permit any citizen to fall below a subsistence-level income.

There is also my query about a modern version of a Theory of Income. That query still awaits some ideas.

No offense here. I require a bushel of salt with every economic theory or -ism that I am asked to consume. MMT may be terrific to you, but to me its a tad wonkish and nerdy. It has to be easily accessible to lay folk. And poor olde Keynes. Nice guy. But his theory cannot stand up in a situation when the Production/Consumption economy it was founded upon has been overpowered by the FIRE economy starting in the late ’70s and early ’80s. There was no InterNet in 1936. Also, those 600 mill or so folk in Chindia were too busy scratching a living in the dirt, not working in modern factories and offices.

How much QE has been inserted so far? And the nett results? As I said, its the math.

ps: I spotted a few mistakes – how does the Preview work? It won’t accept my corrections! It is an edit function?

“That is the job of the private sectors – in aggregate.”

The private sector can’t and won’t do that.

The Paradox of Productivity prevents it from doing so (once you no longer require all the labour, you can never generate sufficient effective demand to purchase all the output at full capacity. So you never operate at full capacity).

Essentially you can’t sell output to the machines that make it.

So if you believe that the private sector will ride to the rescue, then you’re already doomed by the mathematics.

As we become more productive the dependency ratio has to rise to maintain output. That means giving more and more people income, and finding more and more people something to do.

Hi, Neil, Thanks for that.

“The private sector can’t and won’t do that.”

BINGO! So what does that tell you? It cannot be done! There are physical limits to improvements to productivity – the final outcome is that you eliminate humans altogether, which leads us to :-

“Essentially you can’t sell output to the machines that make it.”

BINGO^2!!

You need more and more folk with more and more incomes. And, how, do they come by those incomes? Scrap the machines and give folk the work?

” That means giving more and more people income, and finding more and more people something to do.”

Now you’re sucking that diesel! Something to do? Any suggestions.

Earth! We have a situation! It really is the math. Those exponentials are a real bitch. They defy the rule which says that sentiment always trumps reason.

Now its back to trying to square that polygon with an infinite number of sides (ever read Flatland by Edwin Abbot?). No modern or contemporary theory of economics or money will sort out this mess. Its back to basic Political Economy. And those that we elect are just going to have to bite down hard and start to distribute those scarce, and getting scarcier (sic), resources, and make themselves quite unpopular as they do so. Think they’re up to it? Neither do I!

Interesting times, as they say.

“Something to do? Any suggestions.”

Everybody needs something to do, every day. Preferably something better than drinking beer and watching Sky TV waiting for the day to end.

And it ain’t that difficult.

Take the paper clip challenge and become more creative.

Perhaps instead of having the banks create government debt which they then buy banks troubled assets with, the government could instead create debt by lending money to citizens as a substitute for welfare. You could set this at subsistence + 10%. Anyone owing money to the gov. would pay tax at 30% on anything else they earned, but working would not interfere with their right to accept more debt from the gov. The only tax allowance would be a personal one set at the same level as the s+10, tax would be at 20% on the rest. In order to recover the debt a turnover tax of 25% could be levied on mature sectors of the economy [say where 6 or fewer players had 2/3 of the market] this would give the possibility of debt jubilees which individuals could apply for when they owed the equivalent of 7 years debt, this could be done by juries drawn from the community where the debtor lives. Enough.

Great blog btw.

Neil W: Beer, burgers and Bingo. Just what I had in mind, 😎

But those are not necessaries – they’re only possible out of your disposable income. Ditto for the state, it has to have a disposable income also. So how is this done? Not looking good!

S’OK: I’ll skip that paper clip thingy. I have some trickier DIY stuff on my mind.

Johnm33: Hi, there. I have this sinking feeling that governments are rapidly approaching the – “Your Card is Declined” moment. You know, when your creditors realize that not only will they never get any of their faked-up money back, but the interest is un-payable also.

The sooner economists leave their dodgy theories and useless ‘laws’ behind them, and start to concentrate on the problems associated with a physical system – the better. Is this likely? I doubt it. But one never should say never!

No offense lads, but you do know what the Permagrowth paradigm is? A simple Yes/No will suffice. The FIRE economy? The Export-land Model of Liquid Hydrocarbon Fuels? And, the late Albert Bartlett’s ideas, views, opinions and beliefs? Just curious, is all.

Thanks for the comments. Appreciated.

“Ditto for the state, it has to have a disposable income also”

No it doesn’t. The state’s “disposable income” is anything real within its jurisdiction left unused or under-utilised.

Try reading the stuff on the site. You might learn something.

@ Neil W: I think we may be talking about different things. I’m talking about income, as in money, (and not just cash, mind). Folk have to have income to live – necessaries + some extra. This income has to come from some source. In the case of the state its income comes via taxes and excise duties. There may indeed be other things available – but you would have to ‘liquify’ them first.

The gov then decides how to distribute its income, and if the gov decides to ‘spend’ more than its income, where does it get the income extra from? Emit more currency? = devaluation. That’s hardly a cheerful option. Borrowing? If its borrowing (a deficit budget, then that’s = Negative Income – yes? Putting it on the state Credit Card. Now, how long can this Negative Income stuff continue before there is a crisis? – because one is guaranteed, absent a matching an annual, incremental increase in aggregate (+ve) economic activity (ie: G*P – new debt). Yes?

I am reading the material on the site. And, it will take a while. And, I do learn! Often I have to re-jig stuff I have learned. I did pose several Qs to you. Knowledge and understanding of them is essential in order to engage in any sort of meaningful intellectual exchange about this current, and far from over, crisis. If you are not familiar with them, then fair enough.

Thanks again. See you!

“In the case of the state its income comes via taxes and excise duties.”

No it doesn’t.

The state’s income comes from its own prior spending.

You have fallen into the trap of linearising a cycle from a particular point and that has clouded your view. Follow the cycle around and you’ll see this particular snake has hold of its own tail.

The state spends on an infinite overdraft at the bank that it owns – the central bank. For every 100 units it spends it will generate 100 units of taxation for any positive tax rate – via the sequence of induced real transactions. The only thing that delays that is if people don’t spend everything straight away. In other words they save.

So when a state spends money, it automagically generates the required taxation and monetary savings to offset that spending.

The only question is whether there are real resources available in the economy for the state to command.

Brian: As Neil’s explanation of the false statement In the case of the state its income comes via taxes and excise duties. shows, the problem is not with what you don’t know, but with what you “know” that ain’t so.

An example. I am writing this from a McDonalds. A while ago at a nearby McD’s, a kind and generous worker there gave me a coupon for a free Southwest Chicken Wrap, from her monthly allotment of coupons. The manager came walked by, smiled and said – “what you doing, giving away coupons to customers again”?

I used the coupon a few days later – because the Southwest Chicken Wrap was a new item that wasn’t for sale yet. My coupon was thus like a bond, rather than a current coupon, like currency, like money, like a free hamburger coupon, a coupon immediately redeemable for something McDs sells.

But the question is – where did McDonald’s get their coupons? Did it get them from their supply of hamburger or Southwest Chicken Wrap coupons that existed since time immemorial : the Immaculate Conception of Money theory – see Lerner. Did it get them from mugging the hardworking kind workers of their supply of McD coupons? (which came from uhhhh, where?) : The state’s ” income comes via taxes and excise duties” theory? Does McDonald’s get its coupon for hamburgers by offering its workers SW chicken wrap coupons only redeemable in the mystical, uncertain future, for the worker’s hamburger coupons, which McDonald’s desperately needs to be able to move hamburgers, I guess? (The government needs to “borrow” / sell bonds theory.)

But where did the coupons come from really? The hamburger coupons, like the chicken wrap coupons, they came from McDonald’s printing them, by “spending” them into existence. What is called government “borrowing” is just the government draining the “reserve” supply of hamburger coupons by offering chickenwrap coupons in exchange. That is all it is – thinking it helps “fund” a government is ridiculous. Sure, there might be situations where it is a sensible thing to do – but it ain’t really how McDonald’s or a government does its business.

The math says No! – and that’s it. Maybe I’m missing something here, and if so, I would really welcome some enlightenment on the matter.

Quite right. What you’re missing is that the math doesn’t “say No!” Nothing has been set up carefully, mathematically, nor are the arguments suggested by, implicit in your monetary statements mathematical or correct. Rather, they are just “intricate reasons” adduced by people who understand little economics or mathematics, to support conclusions which are preposterous when looked at rationally and carefully, or from common sense & intuition.

@ Neil W: Interesting explanation. Leave it with me whilst I digest it. Its puzzling.

@ Some Guy: Nicely put, ” … but with what you “know” that ain’t so.” So what do I ‘dump’? Unlearning something is a tricky enterprise. Much more difficult than learning.

“the Immaculate Conception of Money theory” Brilliant!

The remainder of your comment is very difficult to comprehend. I’ll print both comments and I’ll endeavour to persevere with them! But, how does one ‘drain’ something that has no prior existence? Hmmmmm?

In the real (physical) world, Entropy Rules! But in the world of virtuality all things theoretical are possible, including those Immaculate Conception assumptions. We’ll see.

Thanks again to both of you. I’m learning – I hope!

@ Some Guy: You mentioned Lerner. Would that be A P Lerner? I believe it is customary in academic circles to provide a citation or reference when you wish to quote a particular author. Could you oblige? A particular text or a journal paper. Thank You.

@ Neil W: Having read through your comment, I regret to say that I formed the opinion that it is not credible. It appears facile. I am still unsure as to whether we are both looking at the same side of the same coin, different sides of the same coin, or two different coins. Clarification of this matter might be useful.

“You have fallen into the trap of linearising a cycle from a particular point …”

What trap? Could you explain this.

“…and that has clouded your view.” Maybe, but ….

I looked up “cycles”. Got some interesting results. So I selected the following three: the Beta-oxidation Cycle of Fatty Acids; the Urea Cycle; and the Citric Acid Cycle. These seem to match up to your description of a cycle that it is possible (in theory) to linearize. Curiously, each of them seems to have an ‘entry’ and an ‘exit’ point – they are not an endless-belt, perpetual-motion sort of cycle. Which particular type of cycle have you in mind for money? The one with an entry and exit point, or the endless-belt sort?

@ Some Guy: Interesting epistle. I regret that I fail to ‘see’ the connection between McD Coupons and state and private incomes. No matter.

A bond IS money, by the way. So is debt. And when a debt is paid down money is destroyed.

Your final comment: “Rather, they are just “intricate reasons” adduced by people who understand little economics or mathematics, to support conclusions which are preposterous when looked at rationally and carefully, or from common sense & intuition.”

You have the benefit of being unknown to me. Please try not to abuse this concession. How can you reasonably conclude – from such a short exposure; that I might ‘understand little economics’ (I indeed may!) or that my conclusions (did I make any?) are ‘preposterous’. That’s an argumentative, value judgement adjective by the way. Maybe I do look at stuff irrationally, sloppily, with little common sense and a facile sense of intuition. So what? Did it ever cross your mind that I might have a completely different exposure, than yourself, to things economical. That I may internalize economic concepts in a quite different manner to yourself – hence I develop a quite different understanding of them. What I have, I hold, until someone is helpful enough point me in the direction of empirical evidence to falsify them for me. Rhetoric does not cut it!

I’m still awaiting a response to the questions I posed to both you, and Neil W.

” I regret to say that I formed the opinion that it is not credible.”

Then we can’t help you until you sort out your lack of understand of the accounting.

@ Neil W: Fair enough. Any suggestions as to where I might get information and explanations on what you term ‘the accounting’. Thanks.

@ Neil W: Still no reply?? Does this tell me you do not know, or what?

Neil, MMT is terrific – if its kept in a glass-case. But if you take it out for a spin to test its road worthiness – its wheels will come off. Maybe not immediately – but come off they will. Make sure you have your AA membership up to date!

The Lerner reference is from his Economics of Employment chapter 10: Resistance by Capitalists. p.158

Here is the whole section to put it in context.

An important element is the feeling that money is sacred.

Another source of resistance by capitalists is to be found in the feeling that money is something too holy to be touched by human hands. Thought on this subject is inhibited by the declaration that Functional Finance might involve the creation of money without any increase in the gold or other “backing”. Such “unbacked” money is called “fiat money”, and the phrase is uttered with accents of horror and condemnation as if nobody could doubt that it would mean the end of the world or at least an inflation of the dimensions experienced in Germany in 1923.

Very often this objection seems to be based on the idea that in the normal course of events money is provided not by human action but by Nature with a capital “N”. The idea of money being made (and destroyed) by mere man seems to be a shocking thought. It is as if all the “sound” money which is in existence always has been in existence and always will be in existence – a theory of the immaculate conception of money, original and indestructible. …Note: I am indebted for this expression to my friend Ernest Van den Haag

**********

A bond IS money, by the way. So is debt. And when a debt is paid down money is destroyed. Quite right. (Perhaps better to say bonds are (quasi)money, NFA or money is a form of debt. ) – but this is MMT.

I was not at all criticizing you at the end of my comments, and I apologize that it could be taken that way. I was referring to the very bad, but omnipresent monetary economics of the last few decades – the nonsense you see in most of academia and worse, in common discourse. The revival – and unprecedented extremism – of these zombie ideas, this intricate – and bad – reasoning toward absurd conclusions was only possible by the book-burning, the burial, the forgetting of the scientifically and empirically superior economics of the middle of the last century, which MMT is a development of.

***

A point of the comparison between McD coupons and state money is that the very question of where the state gets its (monetary) income is as absurd as that of where McDonald’s gets its coupons from.

Statements like “Emit more currency? = devaluation.” are not necessarily or generally true. See Lerner as above.

The things to forget are pretty much everything beyond what everbody (children, the “uneducated” etc) know. Older people who lived through the Depression and the Keynesian era are an exception. They have a better understanding of money, got a superior formal education and were naturally less affected by the fall of the dark age of economic understanding in the 70s.

To say what Neil said in another way:

Surely you agree things could work this way – the way children and the “uneducated” might think:

The state spends/prints/mints/keystrokes money (coupons, bonds) into existence. Some people get it – usually/often for selling some real good, service or labor then acquired by the state, the public. LATER, they redeem/return this money back to the state, for taxes, for buying something from the state. That’s it.

The core of MMT is that is all there is. It IS facile. All the rest you see everywhere about government finance is a load of BS whose primary purpose nowadays is to create confusion, and make people think that black is white and up is down – or that the state gets its income from taxes.

But, how does one ‘drain’ something that has no prior existence? Of course, this is impossible. That’s why taxation has to come after spending. That’s why governments issue bonds after creating the currency/money/reserves that the private sector needs to have in order to buy the bonds. (“The funds to pay taxes and buy government securities come from government spending.”- Mosler) Neil is thinking and talking of things as a cycle – but the best, least confusing and truest place to start is from the government spending.

Finally, things are simplest and closest to how things really are and always were in a modern fiat system like the UK, USA, Canada, Japan, Australia etc. Gold-standard economics and the misbegotten Euro are harder and more confusing, and should be studied after the basic, underlying case.

@ someguy: Thanks for that lengthy reply. I’m just home – been away for a few days. I’ll read thru it. In respect of MMT I am reading Wray’s ‘Primer’, which is very interesting; (few nerdy questions – which will keep). I will also re-read the relevant parts of Howard Olson’s ‘Ecological and General Systems’ which has a lot to say about flows + stocks.

Thanks again.