It’s Wednesday and I just finished a ‘Conversation’ with the Economics Society of Australia, where I talked about Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) and its application to current policy issues. Some of the questions were excellent and challenging to answer, which is the best way. You can view an edited version of the discussion below and…

Ageing, Social Security, and the Intergenerational Debate – Part 2

I am now using Friday’s blog space to provide draft versions of the Modern Monetary Theory textbook that I am writing with my colleague and friend Randy Wray. We expect to publish the text sometime early in 2014. Comments are always welcome. Remember this is a textbook aimed at undergraduate students and so the writing will be different from my usual blog free-for-all. Note also that the text I post is just the work I am doing by way of the first draft so the material posted will not represent the complete text. Further it will change once the two of us have edited it.

Chapter 25 Recent Policy Debates

In this Chapter we consider the following policy debates:

- 25.1: Ageing, Social Security, and the Intergenerational Debate

- 25.2: Twin Deficits and Sustainability Of Budget Deficits

- 25.3: Fixed Versus Flexible Exchange Rates: Optimal Currency Areas, the Bancor, or Floating Rates?

- 25.4: Economic Growth: Demand or Supply Constrained?

- 25.5: Environmental Sustainability and Economic Growth

25.1 Ageing, Social Security, and the Intergenerational Debate

[NOTE: I HAVE EDITED THIS SHORT SECTION FROM PART 1]

The real material standards of living in a nation ultimately depends on the stock of real goods and services that the nation commands and its ability to access those resources. Overtime, productivity growth provides the means for improving standards of living because it provides a nation with greater realised access to those resources for a given cost (resources expended).

When we consider this matter in relation to the broad macroeconomic sectors – government and non-government – the matter becomes more complicated. In a market economy, where goods and services are exchanged for money, the ability to command real goods and services for the non-government sector depends not only on the availability but also on the capacity to fund purchases.

For the government sector, the ability to command real goods and services, which are for sale in the currency that it issues depends only on th availability of those resources.

That is a fundamental difference which should inform our understand of the aeging population issue, which is one of the major debates in macroeconomics because of its implications for fiscal policy choices.

The ageing society debate is at the forefront of calls to reduce government deficits. The debate is driven by the proposition that national governments will not be able to afford to maintain the spending necessary to support the growing demands for medical care and pension support as populations age.

At some point, the argument goes, governments will run out of money and other public spending programs will become heavily compromised.

Some economists support this narrative by advancing arguments about so-called financing gaps which are attempts to extrapolate future drains on public spending in relation to the projected scale of the economy.

In this Section we will show that these estimates of spending shortfalls are in fact constructed on flawed premises, which have led to the erection of an array of complex and voluntary accounting structures that give the impression that a currency-issuing government is financially constrained.

Dependency ratios

A motivating factor in the aeging population debate is the fact that dependency ratios are rising in most advanced nations. What is a dependency ratio and why might it matter?

The total dependency ratio is normally defined in percentage terms as the population of non-working age divided by the working age population. The demarcation between working and non-working age can vary across nations, but, it is typical in most countries for people to be allowed to work after the age of 15 and retire after reaching 64 years of age.

Accordingly, the working age population (15-64 year olds) is seen to be supporting the young and the old. A rising dependency ratio tells us that increasingly less productive workers will generate national income relative to the people who are supported by the income.

If productivity growth was static, then a rising dependency ratio tells us that real material living standards will decline over time.

Another concept used is the aged dependency ratio, which is, in percentage terms, the number of people above retirement age divided by the number of persons of working age.

Similarly, policy makers sometimes refer to the child dependency ratio, which is, in percentage terms, the number of people below the working age divided by the number of persons of working age.

The total dependency ratio is the sum of the two. The dependency ratio can be manipulated by policy makers by, for example, increasing the “retirement age”, which reduces the numerator and increases the denominator.

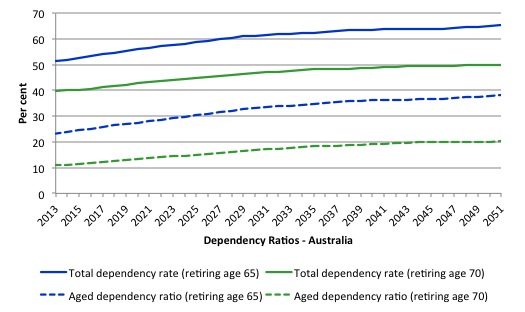

Figure 24.1 shows the total and aged dependency ratios for Australia from June 2013 to June 2051 based on the Australian Bureau of Statistics Series B demographic projections. The dependency ratios assume a a retirement age of 65 and 70 to highlight the impact of a policy decision to increase the retirement age.

Figure 24.1 shows that, based on the official population projections by the Australian Bureau of Statistics, if the government increased the retirement age from 65 (as it is in 2013) to 70 years of age, the dependency ratio in 2051 would fall from a projected 65.4 per cent to 49.9 per cent. In 2013, the total dependency ratio (assuming a retirement age of 65 years) was 51.3 per cent.

Another way of expressing the dependency ratio is that, for Australia, in 2013 there are 2.03 people of working age to every person who is not of working age. This is projected to fall to 1.54 in 2051.

The aged dependency ratio was 24.5 per cent in 2013 and if the retirement age was held at 65 years this is projected to rise to 38.1 per cent by the 2051. If the retirement age was increased to 70 years of age, the aged dependency ratio would drop to 20.2 per cent by the year 2051.

Thus, policy changes can have rather significant impacts on the dependency ratios.

Figure 24.1 Total and Age Dependency Ratio Projections, 2013-2051, Australia

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics Series B Population Projections.

The standard way of calculating the dependency ratio provides a flawed indication of the relationship between active workers relative to inactive persons, the latter being defined as providing no direct contribution to the production of national income.

The concept of an effective dependency ratio has been developed to address these flaws.

First, the concept of unpaid work is ignored, which as we saw in Chapter 3, is a standard problem of the conventional national accounting framework.

So like all measures that count people in terms of so-called gainful employment, the standard dependency ratio measure ignores major productive activity like housework and child-rearing. The latter omission understates the female contribution to economic growth.

Second, the effective dependency ratio recognises that not everyone of working age, however defined, are actually producing national output and income. There are many people in this age group who are also “dependent”. For example, full-time students, house parents, sick or disabled, the hidden unemployed, and those who have taken early retirement fit this description.

The unemployed and the underemployed should also be included in the category of non-productive people of working age, although the statistician counts them as being economically active within the Labour Force framework.

The inclusion of the unemployed and underemployed significantly impact on the estimated dependency ratio when there is mass unemployment and high rates of underemployment. For example, in August 2013, the Australian labour market data showed that official estimated unemployment was 714,100 and estimated underemployment was 964,300.

Recomputing the dependency ratio (adding these underutilised workers to the numerator and subtracting them from the denominator) produces a total dependency ratio of 69.9 per cent in 2013 compared to the standard estimate of 51.3 per cent.

This analysis shows that for Australia (in 2013), the impact of high labour underutilisation on the dependency ratio is more significant than increasing the retirement age by 5 years.

As we will see, persistent labour underutilisation also exacerbates the implications of a rising dependency ratio because it has adverse impacts on the growth in labour productivity.

Do dependency ratios matter?

A dominant view in the public debate is that a rising dependency ratio indicates that more workers will be relying on the state for pension and health support and less workers will be contributing to the government’s tax base.

The implication of a rising ratio of economically inactive compared to economically active is that the latter will have to bear higher tax burdens to support the increased government spending.

As time passes, it is argued that the state enters a fiscal crisis driven by unsustainable deficits and debt obligations.

These claims underpin the dominant theme used by governments, business lobbyists, and economists to justify a preference for the pursuit of budget surpluses in the context of aeging populations.

For example, in the US there is constant pressure on government to privatise the US social security system as a means of keeping it solvent. Similarly, in Australia, the so-called intergenerational debate, which began in the mid-1990s and is still a powerful political force, was central to the pursuit of budget surpluses by successive federal regimes.

The argument used to support the preference for surpluses in the context of an aeging population is simple:

- The budget deficit cannot be allowed to reach some projected level because the increasing public debt would push interest rates up and ‘crowd out’ productive private investment.

- Increasing debt will impose higher future taxation burdens for future generations, which will reduce their future disposable incomes and erode work incentives.

- People must work longer (retirement ages must be lifted) to accumulate more funds to finance their own retirements and incentives for people to increase the birth rate should be introduced.

- For some nations, higher levels of immigration are required to reverse the ageing bias in the population.

What is the veracity of these arguments from the perspective of the macroeconomic framework we have introduced and developed within this textbook?

It is often suggested that budget surpluses are equivalent to accumulation funds that a private citizen might enjoy as a result of persistent saving. Using this metaphor, accumulated budget surpluses are seen as being ‘stored away’ for the future and thus provide the government with the means to deal with increased public expenditure demands that may accompany the ageing population.

TO BE CONTINUED

Conclusion

NEXT WEEK – COMPLETE THIS SUB-SECTION AND MOVE ON DISCUSS OTHER POLICY ISSUES

Saturday Quiz

The Saturday Quiz will be back again tomorrow. It will be of an appropriate order of difficulty (-:

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2013 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

“Dependency ratios”

Is it worth explaining how the dependency ratio relates to the ‘participation rate’.

Is there such a thing as the ‘effective participation rate’? One that adds in those who are inactive but want a job.

“If productivity growth was static, then a rising dependency ratio tells us that real material living standards will decline over time.”

Consider to substitute by a more precise statement as

“If productivity growth was zero, then a rising dependency ratio implies that material living standards will decline over time.”

Today, Queensland government representatives confidently assured me that the health budget would exceed the capacity of the Queensland government to pay for anything else by 2030. Apparently, the Queensland government is powerless to resist econometric trend lines. Cutting social/ health services now, just in case? No worries.

First paragraph, second sentence starts with the word Overtime. Did you mean Over time?

In the case of Health care the systems, it looks like should be working at full tilt now on addressing as may foreseeable problems we can today. Joint replacements, etc.. There are even greater problems awaiting if we fail to address these now, if we might not be able to address them in the future due to increasing dependency ratio.

I find the idea of security security beaing an isolated account (a fund, trust or anything) most misleading and belonging to the neoliberal bias territory.

I think MMT proponents should regard its receipts as a Tax. And its spending as any other government spending, with no necessary relation betwenn taxes and spending.

Bill,

I wonder why don’t they compute dependency ratio (not hte efficient one) as number of people employed/rest of population? is there a reason for not doing that? Seems simpler to me, but maybe i’m missing something?

Bill

Laurence Kotlikoff estimates that the US government’s ‘unfunded liabilities’ are about $202 trillion in total. Do you think his estimate is accurate, or not?

Thanks.

This is a really important topic Bill. The irony is that mainstream economics should also see the problem in this light (a problem of real resources, not of money). The paragraph that will begin where this left off will be very important. Maybe it will go something like this

“Consider this vacuously true fact: no matter how much retired people have saved, when they are retired, they live entirely off of the production of the younger generation. We can forget this sometimes because we have a magical understanding of what money is, but it is true. If you are not producing anything, but you are still consuming, you are snapping up some of the product of people who are working. This is true whether you have piled away money or not.”

http://mattbruenig.com/2013/01/29/response-to-evan-soltas-on-generational-transfers/

The only comment I would make on what you have written is that a historical graph of age dependency ratios is enlightening. Even over the ABS whole projection to 2051 the total dependency ratio doesn’t quite reach the level it was in 1970 (of around 68%). Not so scary then really.