The other day I was asked whether I was happy that the US President was…

Fiscal deficits in Europe help to support growth

I read this article yesterday (published August 12, 2013) – The euro area needs a German miracle – among a group of articles that are concluding that things are on the improve in Europe. I expect a wave of articles which will be arguing that the harsh fiscal austerity has worked. I beg to differ. This article agrees that it is too early to “declare victory” because the austerity has to go further yet. My interpretation of that claim is that the author doesn’t think the ideological agenda to shift the balance of power away from workers has been completed yet. But the substantive point is that the fiscal austerity failed to promote growth and growth has only really shown its face again as the fiscal drag has been relaxed. This relaxation is much less than is required to underpin a sustained recovery at this stage but it is a step in the right direction. Governments, with ECB support, should now expand their deficits further and start eating into their massive pools of unemployment.

In her 1942 book – An Essay on Marxian Economics – Joan Robinson wrote the following (my edition is 1974 and quote is from Page 22):

Voltaire remarked that it is possible to kill a flock of sheep by witchcraft if you give them plenty of arsenic at the same time. The sheep, in this figure, may well stand for the complacent apologists of capitalism; Marx’s penetrating insight and bitter hatred of oppression supply the arsenic, while the labour theory of value provides the incantations.

Let me be clear that I do not share John Robinson’s assessment of the role of the labour theory of value developed by Marx in his overall theoretical exposition.

But I was reminded of this quote when I read the following from the article cited in the introduction:

More structural reform in the euro area periphery will be needed to achieve the adjustment and increase exports. This includes labour markets but perhaps more importantly the numerous regulations at the firm level which hold back competition and increase rents while preventing prices from adjusting. But it would also help if German growth were more substantial.

The German growth is the “arsenic” while the “structural reforms” are the incantations.

I agree with the article that “German public investment is currently one of the lowest in the EU and in many areas the lack of public investment is becoming a bottle neck for growth”.

I also agree that a redirection of the speculative German investment that was largely unproductive in the pre–crisis period towards the domestic German economy would be beneficial for real GDP growth in that nation as well as for other nations which trade with it.

Further, the idea that Germany might invest in human capital development infrastructure (training, education etc) to “facilitate labour migration from countries with high unemployment rates” is exemplary.

The point is that more public spending is required immediately to generate growth in Europe.

There was another article in the British paper, The Independent last week (August 15, 2013) – Eurozone crisis over? The single currency bloc’s long recession has finally ended… – which also weighed into the crisis is over discussion following the release of the latest Eurostat real GDP estimates.

After noting the facts (taken off Eurostat’s data release), the article said that:

The genesis of the eurozone’s crisis was in the vast current account deficits that peripheral nations ran in the first decade of the single currency’s existence.

Which was news to me. The Genesis – that is the beginning – of the crisis was a major collapse in private spending, exacerbated by an ideological obsession with anti-growth fiscal rules (the Stability and Growth Pact) that had suppressed demand for some years and held unemployment well above the full employment levels.

The current account deficits have nothing substantive to do with the collapse in private spending. They may have had distributional consequences once real GDP growth nosedived in the face of the sharp reductions in aggregate demand. But that is another story.

The article does however note that the positive GDP results mask what is really happening in the European economy.

It tells us that:

Current account deficits have indeed fallen, but the data breakdown suggests this has mainly been achieved by crushing imports and high unemployment rather than a surge in exports and gains in competitiveness. The danger is that these deficits will simply rebound if domestic demand returns.

The decline in imports is greater than the growth in exports in many nations, which is unsurprising given the drop in national income.

The article also makes this extraordinary statement:

Despite multiple rounds of austerity, weak growth has led to stubborn budget deficits in several states

We merely need to note the word “Despite” and substitute “Because of” in its stead. I make that suggestion quite independent of the debate about syntax rules where a subordinating conjunction (because) should always introduce a subordinating clause. We stay clear of the rules of English language in this blog (probably because I have forgotten them all!).

So how are those structural reforms doing in terms of enhancing international competitiveness? Brief answer: not very well it would seem. Here is an update on the movements in the Bank of International Settlements monthly Effective exchange rate indices – which they publish for 61 countries from January 1994.

You can learn about this data from their publication – The new BIS effective exchange rate indices – which appeared in the BIS Quarterly Review, March 2006.

There was an earlier publication – Measuring international price and cost competitiveness – which appeared in the BIS Economic Papers, No 39, November 1993.

Real effective exchange rates provide a measure on international competitiveness and are based on information pertaining movements in relative prices and costs, expressed in a common currency. Economists started computing effective exchange rates after the Bretton Woods system collapsed in the early 1970s because that ended the “simple bilateral dollar rate” (Source).

The BIS say that:

An effective exchange rate (EER) provides a better indicator of the macroeconomic effects of exchange rates than any single bilateral rate. A nominal effective exchange rate (NEER) is an index of some weighted average of bilateral exchange rates. A real effective exchange rate (REER) is the NEER adjusted by some measure of relative prices or costs; changes in the REER thus take into account both nominal exchange rate developments and the inflation differential vis-à-vis trading partners. In both policy and market analysis, EERs serve various purposes: as a measure of international competitiveness, as components of monetary/financial conditions indices, as a gauge of the transmission of external shocks, as an intermediate target for monetary policy or as an operational target.2 Therefore, accurate measures of EERs are essential for both policymakers and market participants.

If the REER rises, then we conclude that the nation is less internationally competitive and vice-versa.

The following graph shows movements in real effective exchange rates since January 2008 until July 2013 for selected Eurozone nations and the Euro area overall.

Following the crisis, the general tendency was for real effective exchange rates to decline until mid-2012 However, the real effective exchange rate for Greece in July 2013 (Index value = 99.597) was virtually unchanged compared to the value in January 2008 (Index value = 100).

As the Troika was hacking into public spending and destroying jobs and pushing up poverty rates, Greece became less competitive.

However, we are now seeing a reversal of the rise in competitiveness and the indices are pushing back towards their January 2008 values albeit at different rates.

The Euro nations have not succeeded in significantly increasing their competitiveness despite massive cuts. Internal devaluation is not an effective way to increase international competitiveness. The costs of such a strategy are too high and society breaks down before you get close to the goal.

While the dogma is that a nation that cuts its wages will improve competitiveness is rife, the reality is clearly different.

The problem is that if a nation attempts to improve its international competitiveness by cutting nominal wages in order to reduce real wages and, in turn, unit labour costs it not only undermines aggregate demand but also may damage its productivity performance.

If, for example, workforce morale falls as a result of cuts to nominal wages, it is likely that industrial sabotage and absenteeism will rise, undermining labour productivity.

Further, overall business investment is likely to fall in response in reaction to the extended period of recession and wage cuts, which erodes future productivity growth. Thus there is no guarantee that this sort of strategy will lead to a significant fall in unit labour costs.

There is robust research evidence to support the notion that by paying high wages and offering workers secure employment, firms reap the benefits of higher productivity and the nation sees improvements in its international competitive as a result.

But then why is there growth in the face of the harsh austerity?

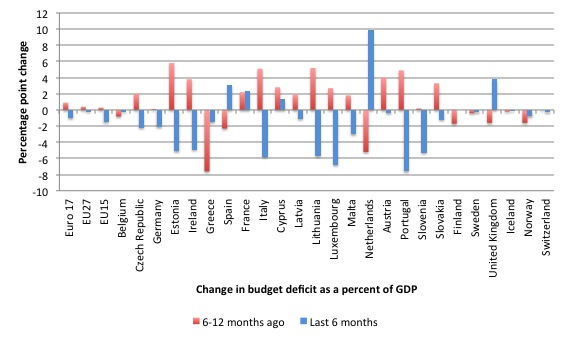

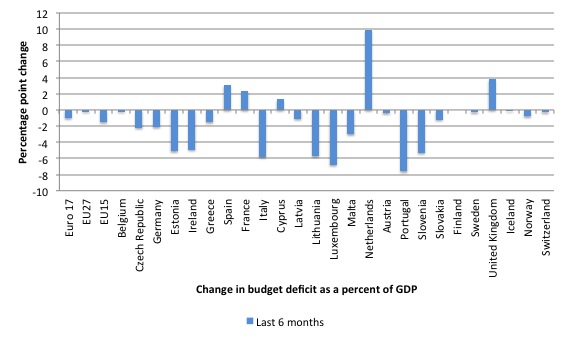

The following graphs shows the change in budget deficits (data from Eurostat) for most European nations over the last 8 quarters (2 years), then the last 6 months compared to the previous 6 months, and finally just the last six months for highlight.

The impact of the fiscal consolidation over the last two years is evident – a positive outcome means that the deficit has shrunk. You can see that for the majority of nations shown (albeit a slim one) the deficits were lower than they were two years ago.

42.8 per cent of the nations had higher deficits in the first-quarter 2013 than they had two years ago.

If we consider the more recent period and split the last 12 months into two semesters then the picture changes considerably. In the first semester of the last 12 month period, only 32 per cent of the nations shown expanded their deficits. In other words, fiscal consolidation (using the conventional terminology) was rampant – and so was the continuing recession.

However, in the second semester of the last 12 months up to the first-quarter 2013, 78.5 per cent of the nation’s expanded their deficits. In other words, there was a fiscal expansion in the vast majority of the nations shown – and there were kernels of growth.

This is the picture over the last 6 months. The fiscal positions may not be appropriate given the massive pools of unemployment but they have moved (mostly) in the right direction – to support increased growth.

Of-course, we don’t have sufficiently detailed data at present to decompose the overall change in the budget deficit outcomes for each nation into structural and cyclical components.

But for the purposes of today’s blog that is not very important. The fact is that when a deficit is rising the public sector is increasing its net spending and increasing its contribution to real GDP growth (which in some circumstances might be expressed as a small negative contribution to real GDP growth).

Conclusion

The fact is that the European growth is showing that when the fiscal austerity is eased, spending rises and so does output growth.

The related data also shows that despite all the structural change agendas, the main target of that change – improved international competitiveness is moving in the opposite direction.

The improved external deficits are thus mainly the legacy of austerity-damaged economies draining import demand than a mass outbreak of exports.

A little musical end for today

And the direction of the real effective exchange rate graphs reminded me of this great song from 1975 from the equally great Australian soul singer Renee Geyer – Heading in the Right Direction.

When you smash economies with harsh cuts to pay, pensions, public investment, health expenditure and force increasing (and historically huge) proportions of the workforce into unemployment, there is little chance that international competitiveness will rise.

The graphs showing continuing deteriorating international competitiveness are thus “heading in the right direction”.

And I also thought you might like to remininisce a little on the fashions of the mid-1970s – those flares were really something else. Did I have a pair? No personal information divulged in that regard but the answer is nyet!

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2013 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

So what’s your solution Bill? Presumably, and judging from your previous articles on this subject, it’s to break up the Eurozone. But you don’t actually say so in the above article, far as I can see.

The only solution you offer is “more public spending is required immediately to generate growth in Europe.” But the problem with that is that with the core being near full employment and the periphery being far from full employment, any increased spending will inevitably be mainly in the periphery which will draw imports into the periphery which will exacerbate their indebtedness. So that’s no solution.

Ralph is correct – the eurozone crisis is a result of a catastrophic scaling up of the banking system (which the powers that be now want to make politically official)

This could only be achieved via the total destruction of the European post 1648 nation state concept (really a smaller bank controlled vassal)

But this destruction of a 400~ year tradition has cascaded into massive real economic losses as people (banking assets) get wiped out as economic & cultural neutron bombs are dropped all over the place.

What remains is the structure of the modern market state but with little substance to carry it as all of the villages ,market towns ,provincial cities and indeed former nation state capitals are destroyed so as to forward a rent to the worlds financial capitals.

Its a quite sick but ingenious scheme that has happened many times before in European history.

The last thing “Europe” needs (whatever that means) is growth………..growth will simply be harvested by the financial capitals.

Given the open nature of modern borders the average euro worker will simply have to deal with more external workers which will reduce the energy consumption per person despite some increased growth in his former country.

This is the lack of control which has made our politics irrelevant.

The model for this is the UK union – The periphery was driven into surplus….Irish workers left the “burning” building and disrupted and drove down English culture and wages.

Its in the interest of the banking system to create a constant state of flux so as to extract the max amount of marrow from its host.

I am afraid its the nature of the beast but we keep forgetting and therefore repeat the same mistakes over and over again.

Bill,

Your 3rd graph appears to confirm that Greece will need further bailouts soon – as austerity albeit at slower rate still rules? Awaiting German elections before announced ?

Netherlands deficit growing even faster than UK – is this unemployment or housing price crash or other factors?

Ralph,

If wages rise in the core this could oftset the increased imports by the periphey.

Dork,

I didn’t actually say anything about banking. My point is that it’s lack of competitiveness in the periphery compared to the core that is the basic EZ problem. If, as Bill says, internal devaluation can’t be made to work then the only option is to abandon the Euro.

As to whether internal devaluation is or isn’t working, it’s certainly not working brilliantly well, far as I can see. But I wish someone would spend serious amounts of money researching this point. Instead, the IMF and OECD witter on about “consolidation”. Staff at the IMF and OECD should all take a dose of laxative: that would get rid of their consolidation fetish.

Paul Krugman recently gave some IMF authors a kick in the whatsit for their latest consolidatory drivel. See:

http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/08/24/the-macroeconomics-of-sisyphus/?_r=0

Re banking, that’s a problem that plagues not just the EZ: it’s a problem for the UK and US etc. I’m not sure that it’s worse in the EZ than elsewhere.

Justin,

Agreed. Wage increases and a few years elevated inflation in the core would come the same thing as wage cuts and price cuts in the periphery.

OK, I agree that most of the improvement seen in deficit countries like Portugal or Spain is due to a bigger fall in demand relative to their main commercial partners. Nevertheless, such reduced demand musn’t result exclusively in lower imports. Another effect could be that tradable goods that were produced and, in the past, consumed in these countries are now available for export. Thus, besides the reduction in total imports, austerity can also result in an increase in total exports, at least temporarily. This double effect may have helped to equilibrate large commercial imbalances but I guess that if internal demand maintains its weakness for a long time the exporting companies migth find incresingly difficult to export the excedents resulting from their weak domestic markets.

Bill: “If, for example, workforce morale falls as a result of cuts to nominal wages, it is likely that industrial sabotage and absenteeism will rise, undermining labour productivity.”

I can attest to the reality that “workforce morale falls as a result of cuts to nominal wages”. I had the misfortune to be in the Federal Public Service in the Howard era. The introduction of workplace bargaining saw our real wages stagnate and even fall relative to inflation. Other rights and conditions also had to be bargained away to merely get these “wage rises” that did not even match real inflation. As I pointed out to others at the time, what is the end result of bargaining away rights and conditions for “rises” that don’t even match inflation? The end result is that you run out of rights and conditions to pawn. What then?

The Workplace Bargaining process was and is highly unfair and rigged against workers. The employer had and has no incentive to bargain in good faith. Indeed, the employer has an incentive to bargain in bad faith. If the employer makes a derisory offer and remains obdurate, this delays the bargaining process indefinitely. During this delay, workers just continue on the same old stagnating pay rate. If and when a bargain is finally struck (invariably it is a bad outcome for workers) then there is no back pay for the delay essentially caused by the employer’s penny-pinching and intransigence.

At the same time we were being exhorted to “make a difference”, “go the extra yard”, be dedicated and so on. In addition, various useless trinkets and awards were offered for service and sometimes for good performance. These were things like coffee cups or key rings with the agency logo on them. This was like glass beads for the natives! I was tremendously angered and insulted by all this. I wouldn’t treat kindergarten children that way.

In my earlier days in the Federal Public Service I would spend hours at home at night developing job aids, spread sheets, PC applications and automated scripts to assist in my work and my calculations at work. Colleagues would use my aids after they were double-checked and approved for accuracy by management and experienced staff. I did all this for nothing of course because I was young, interested and keen.

Of course, I had all this beaten out of me by public industrial relations under the Howard government and the mangerialism that came with it. By the time they were finished with me and my agency, my attitude (barely concealed) was “F*** you!” I didn’t go an extra inch, did the bare minimum I was paid to do and showed no initiative. I went home at the stroke to the second of the end of my day and enjoyed my family life and hobbies with never a constructive thought about work. Many of my younger and very able colleagues bailed out for greener pastures. I was close to retirement so I played the angles and made a nuisance of myself without actually being reprimandable and counsellable. Which of course is the best way to get a redundacy. As soon as they had money for another round of redundancies they were falling over themselves to get rid of me.

Of course none of this is efficient or effective. I mean the demotivating and alienating of good, keen workers with inadequate pay and other absurdities and indignities heaped on them and then paying out money to get rid of them. It’s a damn stupid way to run a country.

@Ralph

The periphery needs to be “competitive” so as to afford imports……

Its the great big pointless hamster wheel of globalization……

Being competitive means destroying peoples lives in the interests of Industrialization (albeit far away industry for these neo liberal economies whose structure is set up to absorb far away products.

So why be competitive if the outcome is destruction ?

Pre 1970/80 these economies internal goods were cheap relative to cash flow & external goods expensive relative to cash flow

Post 1980~ internal goods became expensive relative to cash flow and external goods cheap…..now external goods are expensive and internal goods unavailable or expensive relative to cash flow – cue full scale breakdown crisis.

Its a question of scale – the energy density is no longer available …..its been burned……..global trade can only be sustained via the destruction of the remaining bits of these rump domestic economies as can be seen in Greece and elsewhere.

Real physical economies have been destroyed for a satanic vision of money as a double entry system.

We are dealing with a form of neutron bomb economics.

You don’t understand – we need to smash the machine or the machine will destroy us all.

“But the problem with that is that with the core being near full employment and the periphery being far from full employment, any increased spending will inevitably be mainly in the periphery which will draw imports into the periphery which will exacerbate their indebtedness. So that’s no solution.”

From a German perspective, I beg to differ. At least if you consider whats really going on with the core of the eurozone. Germany being close to full employment is quickly revealed as a myth if you look at the employment data more closely than a first glance. Germany has experienced a massive growth of part-time jobs in the recent decade, the volume of working hours has remained the same for almost 20 years. Official statistics have ben reformed and watered down to exclude all kind of people looking for work. You have to look more closely at the numbers to see that 5 Million Germans are registered as “looking for work” and receiving some kind of unemployment benefit. 3.8 Million more are registered underemployed. That is the official statistics – not counting how many people would like to increase their working hours to increase their income, but are stuck in part-time jobs.

The only federal states of Germany that are remotely close to full-employment are Bavaria (3,6% official unemployment) and Baden-Württemberg (3,9%), all the other states are ranging from around 5-6% unemployment (Hessen, Rheinland-Pfalz) to almost 11% (Mecklemburg Vorpommern, Sachsen-Anhalt, Berlin, Bremen). On average, West German federal states are at 5.8%, east germany at 9,9% unemployment.

Huge investments in infrastructure are needed, in some places, bridges are crumbling to the point where they are closed for traffic. The wages have been suppressed with decreasing real wages over the last 10 years. We are exporting far more than we are importing, with a trade surplus of almost 7% of our GDP.

Clearly, Germany is far from being a happy place with people living far below their productivity, enjoying effectively 7% less than they produce. Sure, we are better off than most european countries, both from the overall standard of living and with the employment situation we have here. But in the end, we are exporting our unemployment to the periphery, while not enjoying the fruits of our own work. How screwed is that?!

The solution lies in increasing demand right here in the center of the eurozone, which would not only decrease our own unemployment (which still has some way to go before reaching full employment levels) and fix some of our infrastructure problems, but through positive wage effects also boost the desire for imported goods, e.g. from southern europe.

Of course, immediate stimulus programs are also needed in southern europe to alleviate the pressure on entire peoples created by austerity measures – but without a rebalancing inside the core the eurozone has not even a remote chance of recovery, as imbalances would persist in the long term.