I have been a consistent critic of the way in which the British Labour Party,…

Massive real wage cuts will not improve growth prospects

There was a column in today’s Australian Financial Review “When the money-go-round slows, everyone suffers” which bemoaned the fact that all the investment bankers, lawyers and accountants that have been making heaps off the massive growth in the financial services sector are now doing it tough. We read that household budgets are being stretched when some woebegone executive suddenly discovers “multiple sets of $20,000 a year private school fees plus family holidays in Aspen” (from Australia). We feel sorry for them don’t we. The parasites of neo-liberalism who in between crafting handsome consulting contracts for themselves fill their days performing largely unproductive functions to our society. The AFR is, of-course, the neo-liberal propaganda machine that feeds the business sector with arguments about how badly they are doing because workers are overpaid and lazy. Yes, there was also an article in today’s edition about excessive wages and labour market regulation. Meanwhile, the latest evidence from Britain is that workers have taken the equivalent of a 15 per cent real wage cut over the period 2007 and 2012. The cuts have undermined nominal wages of workers in jobs rather than being the result of workers shifting to lower paid jobs. That is unprecedented and confirms the suspicions that the austerity agenda is being driven by a desire to win the class war for capital once and for all.

The British Institute for Fiscal Studies has just released a Report – What can wages and employment tell us about the UK’s productivity puzzle? – which paints a sorry picture for workers over the course of this recession, which is characterised as the “longest and deepest slump in a century”.

The UK Guardian article (June 12, 2013) – Workers suffer deepest cut in real wages since records began, IFS shows – wrote that:

The report finds that since the start of the recession real wages have fallen by more than in any comparable five-year period. It also highlights an “unprecedented” drop in productivity as output has tumbled faster than employment.

The amazing thing is that most of these losses have been avoidable. If the government had not baulked at its responsibilities and provided sustained stimulus to allow the private debt issues to work their way out over time the economy would not have entered the massive slump.

A reading of the IFS Report reveals that:

The last time that such a high proportion of workers faced real wage cuts was between 1976 and 1977, when inflation exceeded 15%, while the proportions of nominal wage freezes and cuts are the highest since the series began in the mid 1970s.

So this is an attack on the nominal wages received rather than inflation deflating the real value of those nominal wages (that is, nominal wages growth failing to keep pace with inflation).

The Report studied the evolution of real wages between 2007 and 2012 and found that “aggregate change was -5.3%”.

The UK Guardian article (June 12, 2013) – Workers suffer deepest cut in real wages since records began, IFS shows – notes that normally “real wages rise by 2% a year”, which reflects productivity growth.

In other words since 2007, “people are more than 15% worse off than they would have been if the pre-crisis wage trends had continued”. And that doesn’t take into account the massive wealth losses that have occurred.

The IFS Report investigated whether the real wage cut was due to “compositional factors” – that is, “on the basis of changes to the characteristics of individuals in the workforce and the jobs that they do”.

They found that when compositional changes are controlled for they “would have expected wages to increase by 3.3%, all other things being equal”.

Which means that:

… none of the aggregate wage fall can be explained by changes to the composition of the workforce on the basis of characteristics that we observe and hence must instead all be due to changes to the parameter values associated with (or returns to) particular characteristics instead.

What does that mean?

It means that the massive real wage cuts in the UK over the course of the recession have not been compositional in nature – that is are “not just being driven by individuals being made redundant and having to take lower paid jobs”. The Report finds that:

… there is also strong evidence of substantial nominal and real wage reductions occurring within jobs.

The Report investigates why workers are “so much more likely to have experienced nominal wage freezes or cuts during this recession compared to previous recession”.

They find that there has been a “dramatic decline in trade union membership over the last 30 years … accompanied by a reduction in the proportion of employees covered by collective bargaining, which appears to have made it easier for employers to hold constant or reduce insiders’ wages”.

This is a world-wide trend and one of the defining characteristics of the neo-liberal period – that relentless attack on the capacity of the workers to translate productivity growth into real wages growth.

I have noted the consequences of this in the past. I recently gave a talk in Darwin about this and the working paper to support the presentation is available here – Full employment abandoned: the triumph of ideology over evidence

The deregulation in the labour markets not only created increased job instability and persistently high unemployment but also led to large shifts in national income from wages to profits.

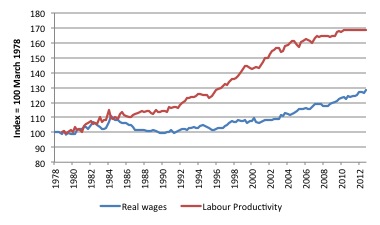

The following graph shows the relationship between real wages and productivity growth in Australia from 1978 to 2012. An recent ILO Report written by Englebert Stockhammer – Why have wage shares fallen? A panel analysis of the determinants of functional income distribution – reports similar trends in other advanced OECD nations.

[Reference: Stockhammer, E. (2013) Why have wage shares fallen? A panel analysis of the determinants of functional income distribution, International Labour Office, Geneva]

First, the wage share in national income has fallen significantly over the last 35 years in most nations.

Second, in the Anglo nations, “a sharp polarisation of personal income distribution has occurred” (Stockhammer, 2013: 2), with the top percentile and decile of the personal income distribution substantially increasing their total shares. The munificence gained at the expense of lower-income workers manifested, in part, as the excessive executive pay deals that emerged in this period.

Up until the early 1980s, real wages and labour productivity typically moved together. As the attacks on the capacity of workers to secure wage increases intensified, a gap between the two opened and widened. The widening gap between real wages and productivity growth manifested as the rising profit share.

In 1975, the Australian wage share was around 62.5 per cent of factor income. By the end of 2012, it was around 54 per cent. Australian government aided this redistribution in a number of ways: privatisation; outsourcing; harsh industrial relations legislation to reduce union power; National Competition Policy and such.

We know what happened next. Imbued with the, now discredited, efficient markets hypothesis, promoted by University of Chicago economists, policy makers bowed to pressures from the financial sector and introduced widespread financial deregulation and reduced their oversight on the banking sector.

This not only led to a massive expansion of the financial sector, but also, set the stage for the transformation of banks from safe deposit havens to global speculators carrying increasing, and ultimately, unknown risks. The massive redistribution of national income to profits provided the banks and hedge funds with the gambling chips to fuel the rapid expansion of the ‘global financial casino’ expanded.

Increasingly, the Gordon Gekkos strutted the stage as celebrities and were cast as important wealth generators. Private returns were high and the lemming rush unstoppable.

But the reality was different. The vast majority of speculative transactions that occur every day in the financial markets are unproductive, in that they are unrelated to the real economy and advancing our welfare.

A substantial portion of the “wealth” generated was illusory and we subsequently discovered that the socialised losses were enormous as the huge, unregulated gambling casino collapsed under its own hubris, criminality and incompetence.

Hark back to the introduction – those poor dears who are now struggling a little with massive private school fees and their ski holidays in the US Rocky Mountains.

But the two arenas of deregulation created a new problem – one that Marxists would call a “realisation” problem. The capitalist dilemma was that real wages had to typically grow in line with productivity to ensure that the goods produced were sold.

So how does economic growth sustain itself when labour productivity growth outstrips the growth in capacity to purchase (the real wage)? This was especially significant in the context of the increasing fiscal drag coming from the public surpluses, which squeezed private purchasing power in many nations during the 1990s and beyond.

The neo-liberal period found a new way. The ‘solution” was found in the rise of so-called ‘financial engineering’, which pushed ever increasing debt onto households and firms. The credit expansion not only sustained the workers’ purchasing power but also delivered an interest bonus to capital while real wages growth continued to be suppressed. Households, in particular, were enticed by lower interest rates and the vehement marketing strategies of the financial engineers. It seemed to good to be true and it was.

The increasing private sector indebtedness – both corporate and household – is another marked characteristic of the neo-liberal period.

In Australia it manifested mostly as increasing household indebtedness. The debt to disposable income ratio stood at 69.1 per cent in March 1996 and by September 2008 had risen to a staggering 153.1 per cent.

Governments, their central banks, and so-called financial industry experts played down any sense of alarm during the pre-crisis period claiming that wealth was growing along with the debt. When the debt bubble burst, significant proportions of the ‘wealth’ vanished leaving many borrowers with massive debts but few assets.

In the UK, over the period 2007 and 2012, there has also been a productivity slowdown due, in part, to the “sharp reduction in business investment over the course of the recent recession, which has been significantly larger than in previous recessions”.

So much for the hoped for Ricardian response that the conservatives claimed justified the imposition of fiscal austerity. There was meant to be an outpouring of private spending as the government announced plans to cut the budget deficit.

Any reasonable observer predicted exactly the opposite – that rising unemployment, real wage cuts, falling wealth and declining sales would kill growth in both consumption and investment.

That is what has happened.

The IFS Study meshes with the evidence provided in a recent report (June 3, 2013) from the International Labour Organization (ILO) – World of Work Report 2013, Repairing the economic and social fabric.

The ILO unfortunately is now a schizoid organisation – still championing workers’ rights to decent work and real wages growth on the one hand, but on the other – buying into the whole “fiscal consolidation” myth.

In the same way that the IMF keeps raving on about “growth friendly austerity” (when there is no such thing), the ILO talks about achieving “a better balance between employment and other macroeconomic objectives” to “achieve a lasting and inclusive recovery”.

The problem is that fiscal consolidation is code for austerity and the ILO appears incapable of understanding that it undermines workers’ rights to decent work and conditions.

In the – World of Work 2013: Country Brief on the United Kingdom – the ILO said that:

An export-led recovery is unlikely in light of the Euro crisis and global economic slowdown, domestic demand becomes particularly important. However, real private sector wage growth has been negative since the onset of the crisis … Yet, CEO pay in the United Kingdom remains elevated and close to levels attained in 2007 … In 2011, CEOs of the 15 largest firms in the United Kingdom earned on average 238 times the annual earnings of the average UK worker. For the average executive this figure stood at 113 times average earnings.

Further, in relation to the weak domestic demand:

Investment, which in 2012 stood at just over 14% of GDP is among the lowest in advanced economies and has fallen by more than 3 percentage points since 2007. The United Kingdom is caught in a vicious spiral of weak aggregate demand and lack of productive investment. Stagnating wages are adversely affecting demand, which in turn is dampening real investment, leading to poor job creation – reinforcing weak demand and so on

However, the ILO cannot make the obvious connection between these correct observations and their advocacy of fiscal consolidation.

They want to:

1. “stimulate investment in the real economy” – yes, that would be good.

2. “Ensure the financial sector acts as an enabler of the real economy” – yes, an essential aspect of any recovery.

3. “Improve design of executive compensation” – yes, but not in the way they suggest (more another day on that).

4. “Improve effectiveness of minimum wage policies” – yes, it would boost the incomes of low wage workers and help arrest the slump in spending.

But where is the elephant?

If domestic demand is the problem (and the solution) and the private sector is locked in a “vicious spiral of weak aggregate demand” because of “stagnating wages” and poor “real investment” then there is only one sector that can provide the spending leadership.

Which means that fiscal consolidation is the opposite to what is required.

The other obvious lesson to be drawn from these studies is that the mainstream macroeconomics idea that private spending responds positively to fiscal austerity (Ricardian Equivalence) is once again shown to be a massive lie.

The concept is so discredited yet is still wheeled out by governments seeking some sophistry to justify their spending cuts.

Conclusion

The point is that the spending cuts and austerity cannot be seen in isolation. They are part of an historical strategy to undermine the gains made over the C20th by workers in terms of real living standards etc.

The neo-liberals have this weird idea that they can take more off the workers and this will further the interests of the few (the takers). What they cannot seem to understand is that the period leading up to the crisis was historically atypical.

Growth was only really possible because of the credit explosion. That will not occur again any time soon. The more they try to deprive the workers of access to productivity growth and at the same time cut fiscal spending the more stagnant the advanced nations will become.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2013 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Bring back the Price and Incomes Accord. In one configuration, workers got big tax cuts thereby boosting their disposable income and keeping them happy; while employers got to make lower nominal wage rises thereby pleasing them and increasing hiring.

“The neo-liberals have this weird idea that they can take more off the workers and this will further the interests of the few (the takers).”

Sorry, the neo-liberals are completely correct, you are just looking at it from the wrong perspective.

In the short run it is surely true, that driving wages down only yields really big profits as a transient when you are still connected to a high-wage economy. The process inevitably runs down, and as people become more impoverished the physical surplus needed for material investments dries up and the economy becomes stagnant, and the profits from cheap labor will decay. Of course. Replacing a $20/hour worker with a 50 cents an hour worker produces enormous profits – but only when there are still customers making $20/hour. When everyone makes 50 cents an hour these easy profits go away.

BUT THAT IS WHAT THE NEO-LIBERALS WANT! It is the inevitable goal of their policies, to bring us back to the society of feudal europe, or imperial China. Feudalism is capitalism without capital – all land is privately owned, there are no meddling government rules. Everything is pure free-market negotiation: a peasant can accept offers to work for bare subsistence wages, or starve. With too many people, and all land owned by a handful of rentiers, there is no need to offer more than the barest living for the average worker. It also cements social control: the fear of being fired or kicked off the estate also allows the rentiers to demand that the peasants follow a certain religion, or shave their heads, or any other whim of the nobility. The end of history! The neoliberal utopia!

There is no need for a market because the rich own everything! They get the yield from their estates from direct right of ownership and have no need of trade or markets or competition or economic growth or technological progress or anything else.

The only problem is that, while overpopulated feudal societies do maximize the lifestyle and power of the rich, they are still weak overall, and they tend to be easy prey for less capital-starved powers. (Think Britain vs. China in the 19th century). But that’s in the long run, and the corrupt rich dream only of making more money now…

Thank you for your consideration,

Timothy Gawne

what is the MMT prescription to increase the wages of the broad masses?

I seem to have missed those blogs

@Kevin Harding

The MMT prescription is to tighten the labor market by a Jobs Guarantee. A tight market will give workers bargaining power and force employers to increase wages and benefits to lure those workers in. Minsky made the point that the War on Poverty failed because it assumed the problem with poverty was the poor rather than a malfunctioning economy. We continue to make the same error today by focusing on welfare, unemployment insurance and job training rather than generating sufficient jobs in the first place.

Once the jobs are there then we can have at it with improving skills, but until then it’s a waste of time.

ben

are there sufficient jobs in India and China?

in the crumbling sweat shops which have eliminated budget clothes production in

the devolped countries

have they tackled the problems of low wages?

a jobs guarantee is certainly better than the complete abdication of macroeconomic

responsibility of current governments

do you think low paid jobs will reverse the documented current history

of growing chasm of wealth and power

in the current climate is it not likely that powerful firms would use a JG for their

benefit?

ben cont

remember many economic systems have provided jobs for all without eliminating poverty

slavery ,feudalism, industrialising capatilism and dictatorial state authority from

hitler to stalin

Minsky would not reduce the problem of poverty to a job guarantee

reduce systemic economic dysfunction to unemployment

Kevin Harding,

Minsky advocated tight labor policy combined with bottom-up wage growth. This can be confirmed by reading the new collection of his work, Jobs, Not Welfare. I have little interest in tilting at the windmills of capitalism while people are suffering now and we can help them now.

amen to that

governments using their monetary power to help the unemployed

just wondered if there were any other mmt policy prescriptions

to tackle the problems highlighted in this blog

the erosion of the living stanards and spending power of those in work

right now governments in the devolping world actually purusing full employment via a mmt

style JG or the necessary fiscal stimulus seems fanciful too

Kevin Harding:right now governments in the devolping world actually purusing full employment via a mmt

style JG or the necessary fiscal stimulus seems fanciful too

Immediate political prospects for sane economic policy in the developing world and elsewhere, may indeed be fanciful, especially as outbreaks of sanity in the developing world are often met by fanatical economic warfare & worse from the “developed” world. But purely economically, what is fanciful – what is risible, preposterous – is that the developing world can afford unemployment, can afford to not pursue fiscal “stimulus” (= not strangling yourself), can afford to not have a JG.

If the developed world, in particular the USA, had a JG, gross, mass poverty and gross inequality would soon be a distant memory. Speaking purely economically, the JG would in short order directly eliminate “the erosion of the living standards and spending power of those in work.” Bill, with academic circumspection, often says the JG is not a panacea. Well, in order to be as radical as reality itself, I always like to go out further on limbs, and I would say the JG damn well IS a panacea, an aspirin the size of the Sun.