It’s Wednesday and I just finished a ‘Conversation’ with the Economics Society of Australia, where I talked about Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) and its application to current policy issues. Some of the questions were excellent and challenging to answer, which is the best way. You can view an edited version of the discussion below and…

Unemployment and inflation – Part 2

I am now using Friday’s blog space to provide draft versions of the Modern Monetary Theory textbook that I am writing with my colleague and friend Randy Wray. We expect to complete the text during 2013 (to be ready in draft form for second semester teaching). Comments are always welcome. Remember this is a textbook aimed at undergraduate students and so the writing will be different from my usual blog free-for-all. Note also that the text I post is just the work I am doing by way of the first draft so the material posted will not represent the complete text. Further it will change once the two of us have edited it.

This is the second part of a Chapter on unemployment and inflation – the first part was:

I am now continuing Section 12.5 on the Quantity Theory of Money …

Chapter 12 – Unemployment and Inflation

MATERIAL HERE NOT REPEATED.

12.5 The Quantity Theory of Money

The Classical theory of employment, that we analysed in detail in Chapter 11, was based on the view that the real variables in the economy – output, productivity, real wages, and employment – were determined by the equilibrium outcome in the labour market.

The real wage was considered to be determined in the labour market, that is, exclusively by labour demand and labour supply. Labour demand was inversely related to the real wage because they asserted that marginal productivity was subject to diminishing returns and the supply of labour was positively related to the real wage because workers would prefer to work more hours as the price of leisure (the real wage) rose.

The real wage is construed in this theory as being the price of leisure in the sense that it represents the other goods and services foregone (via lost income) of an hour of non-work (leisure). The real wage is thus a relative price – of leisure relative to other goods and services.

As we have learned in Chapter 11, the important Classical result is that the interaction between the labour demand and supply functions determines the real level of the economy at any point in time. Aggregate supply of goods and services is determined by the level of employment and the prevailing technology, which maps how much output is forthcoming for a given level of employment. The more productive is labour the higher will the output supply be at each level of employment.

Say’s Law, which follows from the loanable funds doctrine, is then invoked to assume away any problems in matching aggregate demand with this supply of goods and services. The loanable funds doctrine posits that saving and investment will always be brought into balance by movements in the interest rate, which is construed as being the price of today’s consumption relative to future consumption.

The theory thus assumes that two relative prices – the real wage in the labour market and the interest rate in the loans market – ensure that full employment occurs (with zero involuntary unemployment). Knowledge of the general price level was thus irrelevant to explaining the real side of the economy.

This separation between the explanation for the determination of the real economic outcomes and the theory of the general price level is referred to as the classical dichotomy, for obvious reasons. The later Classical economists believed that if the supply of money was, for example, doubled, that there would be no impact on the real performance of the economy. All that would happen is that the price level would double.

The classical dichotomy that emerged in the C19th stands in contradistinction to the earlier ideas developed by economists such as David Hume that there was a trade-off between unemployment and inflation that could be manipulated (in policy terms) by the central bank varying the money supply.

It is of no surprise that the Classical employment model relied, in part, on the notion of a classical dichotomy for its conclusions. It origins were based on a barter model where there is an absence of money and owner producers trade real products. Clearly, this conception of an economy has no application to the monetary economy we live in.

The development of Classical monetary theory was only intended to explain the level and change in the general price level. The main attention of the Classical economists was in trying to understand the supply of output and the accumulation of productive capital (and hence economic growth).

The theory of the general price level that emerged from the classical dichotomy was called the Quantity Theory of Money. The Quantity Theory of Money, had its origins in the work of French economists in the sixteenth century, in particular, Jean Bodin.

Why would we be interested in something a French economist conceived in the sixteenth century? The answer is that in the same way that the main ideas of Classical employment theory still resonate in the public debate (for example, the denial that mass unemployment is the result of a deficiency of aggregate demand), the theory of inflation that arises from the Quantity Theory of Money is still influential and forms the core of what became known as Monetarism in the 1970s.

Economics is not a unified discipline and different schools of thought advance conflicting policy frameworks. Monetarism and its more modern expressions form one such school of thought in macroeconomics and relies on the Quantity Theory of Money for its inflation theory.

We will also see that the crude theory of inflation that emerges from the Quantity Theory of Money has intuitive appeal and is not very different to what we might expect the average lay person would believe – that growth in the money supply causes its value to decline (that is, causes inflation).

The Quantity Theory of Money was very influential in the nineteenth century. The theory begins with what was known as the equation of exchange, which is, at first blush, an accounting identity.

We write the equation as:

(11.1) MV = PY

PY is the nominal value of total output (which you will relate to as the definition of nominal GDP in the national accounts) given P is the price level and Y is real output. Consistent with that definition you will understand that PQ is a flow of output and expenditure.

M is the quantity of money in circulation (the money supply) and V is called the velocity of circulation, which is the average circulation of the money stock. V is thus the turnover of the quantity of money per period in making transactions.

To understand velocity think about the following example. Assume the total stock of money is $100, which is held by the two people that make up this economy. In the current period (say a year), Person A buys goods and services from Person B for $100. In turn, Person B buys goods and services from Person A for $100.

The total transactions equal $200 yet there is only $100 in the economy. Each dollar has thus be used “twice” over the course of the year. So the velocity in this economy is 2.

The money supply is a stock (so many dollars at a point in time). Any given stock of money might turnover several times in any given period in the course of all the myriad of transactions that are made using money.

As we learned in Chapter 4 when we considered stocks and flows, flows add to or subtract from related stocks. But it makes no sense to say that a stock of say $100 is equal to a flow of $100. They are incommensurate concepts in this regard.

The velocity of circulation converts the stock of money into a flow of money and renders the left-hand side of Equation (11.1) commensurate with the right-hand side.

As it stands, Equation (11.1) is a self-evident truth because it is an accounting statement. It is obvious that the total value of spending (MV) will have to equal to the total nominal value of output (PY). In other words, there is no theoretical content in the relationship as it stands.

We thus need to introduce some behavioural elements into Equation (11.1) in order to use it as a theory of the general price level.

In this regard, it is important to see the Quantity Theory of Money and Say’s Law as being mutually reinforcing planks of the Classical theory. The latter was proposed to justify the presumption that full employment output would be continuously supplied and sold, which meant that the former would ensure that changes in the stock of money would only impact on the price level.

As Keynes observed price level changes did not necessarily correlate with changes in the money supply, which led to his rejection of the Quantity Theory of Money.

In turn, his understanding of how the price level could change without a change in the money supply was informed by his rejection of Say’s Law – that is, his recognition that total employment was determined by effective demand and the capitalist monetary economy could easily fall into a state where effective demand was deficient.

But the Classical theorists considered that a flexible real wage would ensure that full employment was attained – at least as a normal state where competition prevailed and there were no “artificial” real wage rigidities imposed.

As a result, they considered Y to be fixed at the full employment output level.

Additionally, they considered V to be constant given that it was determined by customs and payment habits. For example, people are paid on a weekly or fortnightly basis and shop, say, once a week for their needs. These habits were considered to underpin a relative constancy of V.

Figure 11.1 depicts the resulting causality that defines the Quantity Theory of Money explanation of the general price level. The horizontal bars above the V and Y indicate they are assumed to be constant. It follows that changes in M will directly and only impact on P.

Figure 11.1 The Quantity Theory of Money

To understand this theory more deeply it is important to note that the Classical economists considered the role of money to be confined to acting as a medium of exchange to free people from the tyranny of a double coincidence of wants in barter. That is, to overcome the problem that a farmer who had carrots to offer but wanted some plumbing done could not find a plumber desiring any carrots.

Money was seen as lubricating the process of real exchange of goods and services and there was no other reason why a person would wish to hold it.

The underlying view was that if individuals found they had more money than in the past then they would try to spend it. Logically, it followed that they considered a rising stock of money to be associated with higher growth in aggregate demand (spending).

As Figure 11.1 shows, monetary growth (and the assumed extra spending) would directly lead to price rises because the economy was already assumed to be producing at its maximum productive capacity and the habits underpinning velocity were stable.

In Chapter 14, we will consider the evolution of monetary theory and see that one of the central ideas that Keynes used to discredit the Classical theory of prices related to the role of money as a store of value, which allowed individuals to manage uncertainty about asset prices by holding their wealth in its most liquid form.

For now it is worth noting two empirical facts. First, capitalist economies are rarely at full employment. The fact that economies typically operate with spare productive capacity and often with persistently high rates of unemployment means that it is hard to maintain the view that there is no scope for firms to expand real output when there is an increase in nominal aggregate demand growth.

Thus, if there was an increase in availability of credit and borrowers used the deposits that were created by the loans to purchase goods and services, it is likely that firms with excess capacity will respond by increasing real output to maintain market share rather than pushing up prices.

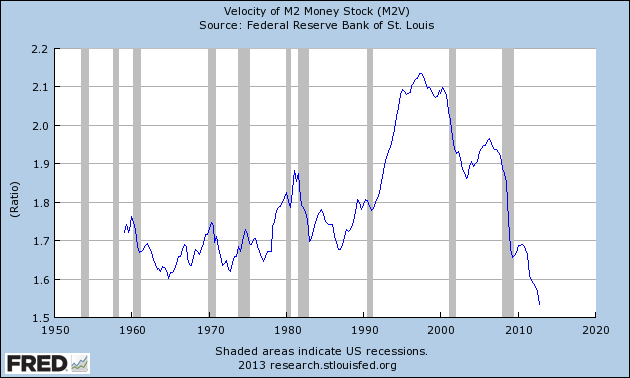

Second, the empirical behaviour of the velocity of circulation demonstrates that the assumption that it is constant is not plausible. Figure 11.2 uses US data provided by the US Federal Reserve Bank and shows the velocity of circulation, constructed as the ratio of nominal GDP to the M2 measure of the money supply.

The US Federal Reserve says that this measure:

… can be thought of as the rate of turnover in the money supply–that is, the number of times one dollar is used to purchase final goods and services included in GDP.

Figure 11.2 Velocity of M2 Money Stock, US, 1950-2012

Data source: US Federal Reserve Bank, St Louis FRED2 database – http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/series/M2V.

[NOTE: in the final version of the text book all graphics will be redone by us to present a uniform format etc]

The conclusion we draw is that the evidence does not support the basic causality that the Quantity Theory of Money offers. The situation is much more complicated than the claim that there is a simple proportionate relationship between increases in the money supply and rises in the general price level.

However, there are major problems with the theory of money that underpins the Quantity Theory of Money and we will explore those issues more fully in Chapter 14.

We now turn to considering the role of the Phillips curve in macroeconomics.

12.6 The Phillips curve

In Chapter 9, we derived what we termed to be a General Aggregate Supply Function (Figure 9.5) and the reverse-L shape. The horizontal segment was explained by the price mark-up rule and the assumption of constant unit costs. In other words, firms in aggregate are assumed to supply as much real output (goods and services) as is demanded at the current price level set up to some capacity limit.

Figure 9.5 became vertical after full employment because beyond that point the economy exhausts its capacity to expand short-run output due to shortages of labour and capital equipment. At that point, firms will be trying to outbid each other for the already fully employed labour resources and in doing so would drive money wages up.

Under normal circumstances, the economy will rarely approach the output level (Y*) which means that for normally encountered utilisation rates the economy faces constant costs.

We acknowledged in Chapter 9, however, that rising costs might be encountered given that all firms are unlikely to hit full capacity simultaneously. Ww noted that the reverse-L shape simplifies the analysis somewhat by assuming that the capacity constraint is reached by all firms in all sectors at the same time.

In reality, bottlenecks in production are likely to occur in some sectors before others and so cost pressures will begin to mount before the overall full capacity output is reached.

This recognition leads us to consider the so-called Phillips curve, which was originally constructed in the work of A.W. Phillips published in 1958, as a relationship between the percentage growth in money wages and the unemployment rate. Later, economists constructed the relationship as being between the general inflation rate and the unemployment rate.

In the pre-Keynesian era, unemployment was considered to be a voluntary state and full employment was thus defined in terms of the employment level determined by the intersection of labour demand and labour supply. So by construction, full employment reflected the optimal outcome of maximising, rational and voluntary decision making by workers and firms. At the so-called full employment real wage, any worker wanting work could find an employer willing to offer the desired hours of employment and any employer could fill their desired offer of hours from the services of willing employees.

In the Section 12.4, we discussed the fact that the trade-off between inflation and unemployment had been a subject of discussion since the time of the Classical economists, but it never had a prominent place in the debate and was dominated by the evolution of the Quantity Theory of Money.

In the 1950s, this changed and the Phillips curve became a centrepiece of macroeconomic analysis. In 1958, New Zealand economist Bill Phillips published a statistical study, which showed the relationship between the unemployment rate and the proportionate rate of change in money-wage rates for the United Kingdom. He studied that relationship for the period 1861 to 1957.

[REFERENCE: Phillips, A.W. (1958) ‘The Relation between Unemployment and the Rate of Change of Money Wage Rates in the United Kingdom, 1861-1957’, Economica, 25(100), 283-299. The link is if you have a subscription at your library to JSTOR.]

Phillips believed that given that money wage costs represent a high proportion of total costs that movements in money wage rates will drive movements in the general price level.

The Phillips curve has been used by macroeconomists to link the level of economic activity to the movement in the price level. In the Phillips curve framework, the level of economic activity is represented by the unemployment rate. The presumption is that when the unemployment rate rises above some irreducible minimum then economic activity is declining and as the unemployment rate moves towards that irreducible minimum the economy moves closer to full capacity and full employment.

We will see in a later section that the Phillips curve and Okun’s Law, which links changes in the unemployment rate to output gaps (the difference between potential output and actual output) coexist comfortably in macroeconomic theory. The latter provides the extra link between unemployment and output.

In some textbooks you will find inflation models that conflate the two concepts (Phillips curve and Okuns’ Law) and directly relate the inflation rate to the output gap. We prefer for reasons that will be obvious not to take that approach in this text book.

Figure 12.3 shows a stylised Phillips curve.

TO BE CONTINUED

Conclusion

NEXT TIME I WILL FINISH THE ORIGINAL PHILLIPS CURVE AND CONSIDER THE RESPONSES TO IT LEADING UP TO THE EVOLUTION OF THE NATURAL RATE OF UNEMPLOYMENT APPROACH WHICH STILL DOMINATES.

Saturday Quiz

The Saturday Quiz will be back again tomorrow. It will be of an appropriate order of difficulty (-:

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2013 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

FYI (off-topic): Thomas Palley is back with a trashing of MMT that is attracting some early attention, “A critique of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT)“, including a rant on how it ignores the Phillips Curve. (Note that he seems to be completely unaware of you and your work on MMT and the JG.) Palley was last heard from in the dust up (back in July) over who should get credit for first identifying the flawed nature of the Euro.

“Thomas Palley is back with a trashing of MMT that is attracting some early attention”

More a threshing given that it is full of strawmen that have been asked and answered so many times. It’s less of an academic piece of work and more of a work of propaganda.

A pity really since it doesn’t help move us forward to a sensible policy design.

Dear Bill,

it’s very rewarding to see you and Randall displaying a profound historical framework to allow for an understanding of positions you personally don’t share. Seems like an example of true erudition to me that not too many mainstream economists should be able to match.

Yours, Erik

I don’t know the full range of chapters planned for the textbook. My suggestion would be that a final chapter on sustainability and renewability needs to be included. It needs to be pointed out (to young students facing a difficult future) that MMT principles will assist the necessary transition from an endless growth material economy to a steady state material economy. It needs to be pointed out too that reaching the plateau of material growth does not mean reaching a plateau in qualitative growth. Knowledge, technology, medicine and human services can all continue to grow and improve in qualitative terms. For a very long time quantitative growth in knowledge, philosophy, ethics and humane elightenment is still possible in theory.

In additon, a huge transition and remediation project ought to keep all the potential workforce employed for the next 100 years at least. We need to transition from;

(a) a fossil fuels economy to an electrical economy powered by solar and wind.

(b) a private automobile economy to a mass transit economy supplemented by walking and cycling.

(c) energy wasting set ups to energy saving designs (complete redesign of urban infrastructure)

(c) a consumerist fantasy “cornucopia” culture which extravagantly wastes resources to a sober, sensible and forward looking culture focused on long term quality survival and based on deeper more ethical, more humane values and better environmental values.

The Zero Carbon Emissions stationary energy plan for Australia would make a good case study in the big infrastructure projects we need to run to employ all people and prepare a sustainable future.

I have elsewhere (in this blog) expressed my personal opinion that we are already past the point of safe return (overshoot) and that a catastrophic collapse is now almost inevitable. This is not the thing to say to young people. We have to give them hope and methods and they might just find a way. After all, I have 2 young adult (under 21) student children and I hope they have a future.

Also off topic but about the textbook:

I would strongly recommend a chapter on the (actual) history of money, as debt since the time of Babylonia, and also on the state money that is simply backed by taxes. All students are somehow acquainted with the standard fable: barter->commodity money. And everybody thinks of the government as using money, not creating money.

Best regards.

I do question Thomas Palley’s mentioning inflation and political economy and then failing to mention the following (or did I miss it?);

(1) Inflation effects of unrestrained bank lending, debt money creation, CDOs, derivatives, junk bonds, asset speculation, excessive executive remuneration and the various ponzi schemes of financial capital. Did any of these get a mention? It seems to me that the inflationary effects of a Job Guarantee could be easily offset by controlling those factors.

(2) The depressing of real wages and the increase in the profit share to capital.

(3) Did Palley ever once mention the effects of orthodox neocon economics on the unemployed? Real people in real poverty without a job? IThe protection of accumulated capital from inflation seemed far more important to him than the fates of real people.

(4) Insitutional arrangments (centering around central banks, govt borrowing and fiat currency) were mentioned as if they were obstacles which can’t be changed for some fundamental reason. There is no fundamental reason why they can’t be changed. It is only the interests of the capitalist class which demand they not be changed.

The bias of these orthodox economists is revealed by what they leave out. No mention of the fate and human cost for the unemployed, let along the cost in foregone productivity. No mention of limiting the powers of financial capital in the interests of workers and ordinary citizens. No mention of a fair distribution between labour and capital. No mention of class or class interests at all; a total pretence that economics is purely a technical discipline. It’s brazen intellectual dishonesty to mention the term political economy without mentioning the obvious biased interests of the monied class.

Palley’s definition of “political economy” is “the status quo”. The status quo is extant (obviously) and unquestionable in any fundamental way. It’s implied that it’s OK to tinker a little at the edges but no fundamental changes are to be countenanced. Clearly, if that’s the definition of political economy then nothing can ever be changed. It’s circular logic.

MMT has reached the ‘attack phase’. Bring on the heavyweights, the big guns, the Very Serious People, to the arena.

Palley brings nothing to the table that hadn’t already been doomed to failure more than eighty years ago.

Real balance effects ? Seriously. Have a look at some empirical studies.