I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Neo-liberalism fails – time to wake up to that

Regular readers will know that I place the shifts in the distribution of national income (at the sectoral level) as one of the keys to understanding the current economic crisis and the what needs to be done to get out of it. I covered this early on in this blog – The origins of the economic crisis. The mainstream press is now finally latching on to this issue, which is good but sadly the media is still allowing itself to be captured by mainstream economists who have a particular and wrong view of what has been happening, why it has occurred and what the implications of it are for public policy. The fundamental changes that are needed to policy frameworks and societal narratives before the crisis is full resolved are still so far off the radar though. Until we start promoting discussions such as that which follows there will be only limited progress to a sustainable solution.

The New York Times Sunday Review (January 12, 2012) published an interesting article – Our Economic Pickle – which focused on what it termed a “major factor contributing to income inequality” in the US – “stagnant wages”.

It reports recent cases such as the US iconic firm Caterpillar which “reported record profits last year” but “insisted on a six-year wage freeze for many of its blue-collar workers”. That is not an isolated case. Indeed it is the norm and is one of the defining characteristics of the neo-liberal era that has dominated economic policy making over the last three decades.

There are two concepts of – income distribution – that economists consider.

First, the so-called size distribution of income or personal income distribution, which focuses on distribution of income across households or individuals. Often the data is expressed in percentiles (each 1 per cent from bottom to top), deciles (ten groups each representing 10 per cent of the total income), quintiles (five groups each representing 20 per cent of the total income) or quartiles (self-explanatory).

Various summary measures are used to demonstrate the income inequality. For example, the share of the top 10 per cent to the bottom 10 per cent. The Gini coefficient is another summary measure used in this type of analysis.

Second, the functional distribution of income or the factor shares approach, which divides national income up by what economists call the broad claimants on production – the so-called “factors of production” – labour, capital, and rent. Other classifications also include government given it stakes a claim on production when it taxes and provides subsidies (a negative claim).

While orthodox economists argue that the shares reflect “contributions to production” (via the erroneous marginal productivity theory), Post Keynesians (and proponents of Modern Monetary Theory) do not place this emphasis given the class relations that government who gets what. Profits are a return on ownership not contribution.

The distribution of national income is often summarised by the wage share and the profit share and it is that context that this blog proceeds.

This academic article (from 1954) – Functional and Size Distributions of Income and Their Meaning – is a good starting point for understanding the two concepts in more detail, although you need a JSTOR library subscription to access it.

[Full Reference: G. Garvy (1954) ‘Functional and Size Distributions of Income and Their Meaning’, The American Economic Review, 44(2), Papers and Proceedings of the Sixty-sixth Annual Meeting of the American Economic Association (May, 1954), 236-253]

Incidentally, given the recent death of RSS creator and Internet activist Aaron Swartz it is worth noting that he had been charged with hacking into JSTOR in order to distribute the material on an open source basis. JSTOR is an incredible on-line archive of old academic journals that many libraries have culled under pressure of space.

The charges were equivalent as this MSNBC report (January 13, 2013) – The brilliant mind, righteous heart of Aaron Swartz will be missed – said that we:

… should also know that at the time of his death Aaron was being prosecuted by the federal government and threatened with up to 35 years in prison and $1 million in fines for the crime of – and I’m not exaggerating here – downloading too many free articles from the online database of scholarly work JSTOR. Aaron had allegedly used a simple computer script to use MIT’s network to massively download academic articles from the database that he himself had legitimate access to, almost 5 million in all, with the intent, prosecutors alleged, of making them freely available. You should know that despite JSTOR declining to press charges or pursue prosecution, federal prosecutors dropped a staggering 13 count felony indictment on Aaron for his alleged actions

JSTOR has published the following – statement – about the death of Aaron Swartz

The scale of our societies under neo-liberalism have become very screwed. Consider this situation against the IMF last week admitting that it had systematically produced terrible forecasts over many years and used public expenditure multipliers that they have now revealed were not only wrong quantitatively but the quantitative errors were so large that they produced exactly the opposite conclusion to reality about proposed government policy options.

The also used these incorrect multipliers and resulting grossly inaccurate forecasts were used to justify their bullying Eurozone governments (and other nations) in harsh fiscal austerity, which has caused millions to lose their jobs and their life savings.

Why aren’t the bosses and the technicians at the IMF who oversaw that incompetence and malpractice being prosecuted?

Anyway, back to the topic at hand, which builds on the notion that the scale of our societies has become very screwed.

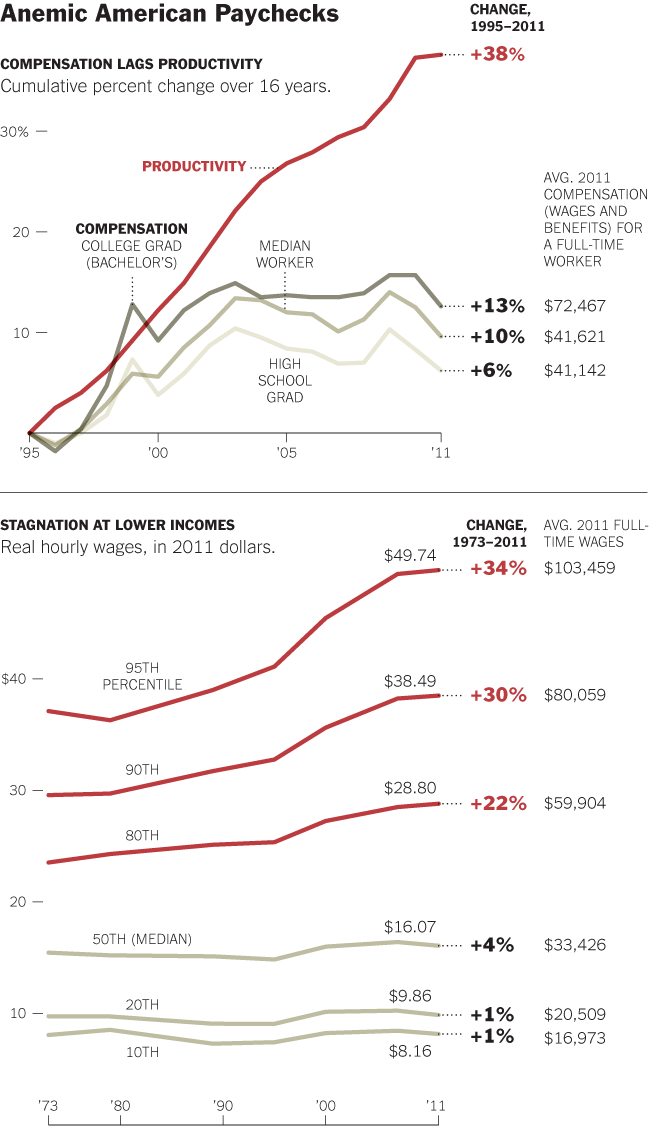

The NYTs article produced this marvellous graphic which is self-explanatory.

The NYTs article quotes a Harvard labour economist as saying:

For the great bulk of workers, labor’s shrinking share is even worse than the statistics show, when one considers that a sizable – and growing – chunk of overall wages goes to the top 1 percent: senior corporate executives, Wall Street professionals, Hollywood stars, pop singers and professional athletes. The share of wages going to the top 1 percent climbed to 12.9 percent in 2010, from 7.3 percent in 1979.

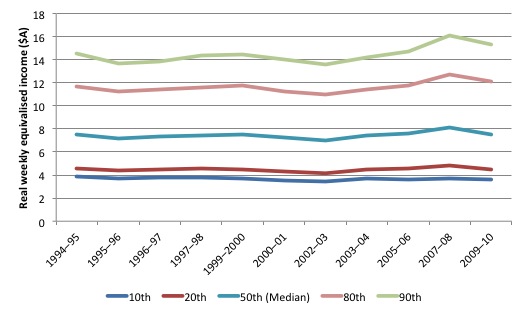

While the same data is not easy to get for Australia (within my allocated blog writing time today at any rate), the following graph provides some insight.

It makes use of the ABS – Household Income and Income Distribution, Australia, 2009-10 – data. The latest edition is 2009-10 and we will get 2011-12 around August this year. My guess from related data is that the inequality that is demonstrated in the following graph and table will have worsened because the top percentiles will have recovered from their temporary setback during the economic crisis.

The graph shows Income per week at top of selected percentiles (in this case the 10th, 20th, 50th (Median), 80th and 90th). I used the CPI to convert the nominal weekly income into real equivalents.

While the degree to which the top income cohorts have outstripped the lower groups is less than in the US, the widening gap is still pronounced. Workers in the bottom two deciles have gone backwards in real terms while those in the top two deciles have made strong real gains.

The disparity would have been worse had I had comparable data going back to the 1970s and 1980s. The widening really started in earnest in the 1980s.

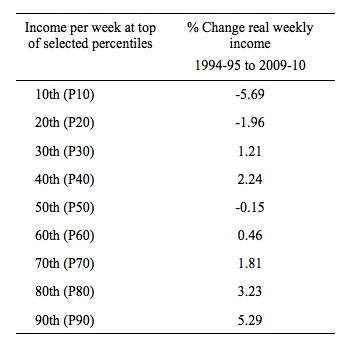

The following Table shows the percentage change in real weekly income for the percentiles from 1994-95 to 2009-10.

The degree of inequality shown in the Graph and Table is downward biased by not being able to decompose the top decile into individual percentiles. While there is considerable variation between the top quintile and the rest, there is also considerable variation gain within the top decile.

In this blog – I feel good knowing there are libraries full of books – I introduced the concept of the Parade of Dwarfs. It was came from a book written by Dutch economist Jan Pen (Income Distribution, 1971, Penguin). There was an interesting article in the Atlantic Magazine in 2006 about this – The Height of Inequality – which traced how the productivity gains in the US had been siphoned off by the few at the top-end of the income distribution.

The Atlantic Magazine article described Pen’s Parade as follows (and provided this graphical depiction of the Parade):

Suppose that every person in the economy walks by, as if in a parade. Imagine that the parade takes exactly an hour to pass, and that the marchers are arranged in order of income, with the lowest incomes at the front and the highest at the back. Also imagine that the heights of the people in the parade are proportional to what they make: those earning the average income will be of average height, those earning twice the average income will be twice the average height, and so on. We spectators, let us imagine, are also of average height …

As the parade begins … the marchers cannot be seen at all. They are walking upside down, with their heads underground-owners of loss-making businesses, most likely. Very soon, upright marchers begin to pass by, but they are tiny. For five minutes or so, the observers are peering down at people just inches high-old people and youngsters, mainly; people without regular work, who make a little from odd jobs. Ten minutes in, the full-time labor force has arrived: to begin with, mainly unskilled manual and clerical workers, burger flippers, shop assistants, and the like, standing about waist-high to the observers. And at this point things start to get dull, because there are so very many of these very small people. The minutes pass, and pass, and they keep on coming.

By about halfway through the parade … the observers might expect to be looking people in the eye-people of average height ought to be in the middle. But no, the marchers are still quite small, these experienced tradespeople, skilled industrial workers, trained office staff, and so on-not yet five feet tall, many of them. On and on they come.

It takes about forty-five minutes-the parade is drawing to a close-before the marchers are as tall as the observers. Heights are visibly rising by this point, but even now not very fast. In the final six minutes, however, when people with earnings in the top 10 percent begin to arrive, things get weird again. Heights begin to surge upward at a madly accelerating rate. Doctors, lawyers, and senior civil servants twenty feet tall speed by. Moments later, successful corporate executives, bankers, stockbrokers-peering down from fifty feet, 100 feet, 500 feet. In the last few seconds you glimpse pop stars, movie stars, the most successful entrepreneurs. You can see only up to their knees … And if you blink, you’ll miss them altogether. At the very end of the parade … the sole of … [the last person] … is hundreds of feet thick.

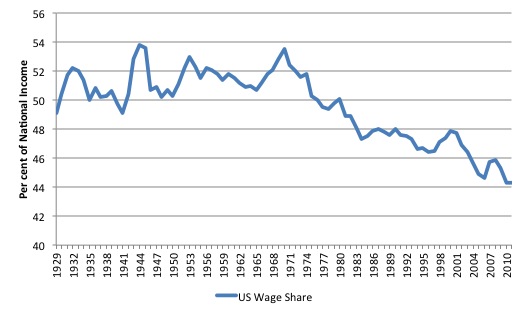

What has been going on at the functional distributional level in the US and Australia?

The US wage share data comes from the US Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) – National Accounts Interactive Data – and the graph shows the annual movement from 1929 to 2011. The most recent peak of the series was in 1970 (53.5 per cent).

There has been a dramatic redistribution of income towards profits in the US over this period. Prior to that the wage share had grown steadily from 1929 through the 1960s peaking at 60.1 per cent in 1980s. After that time, the share has fallen again.

The NYTs article cited at the outset concluded that:

Wages have fallen to a record low as a share of America’s gross domestic product. Until 1975, wages nearly always accounted for more than 50 percent of the nation’s G.D.P., but last year wages fell to a record low of 43.5 percent. Since 2001, when the wage share was 49 percent, there has been a steep slide.

The NYTs article quotes a Harvard labour economist as saying:

We went almost a century where the labor share was pretty stable and we shared prosperity … What we’re seeing now is very disquieting.

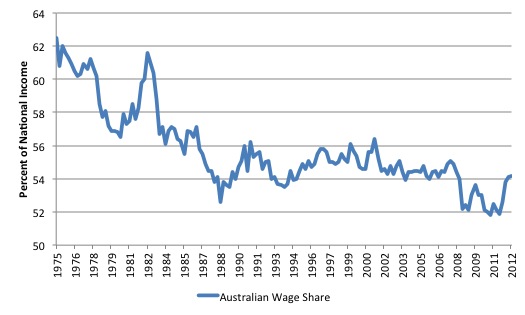

The Australian wage share data comes from the ABS National Accounts file – Table 20. Selected Analytical Series .

The following graph shows the movement in the wage share the March quarter 1975 (when it was 62.5 per cent) to the September-quarter 2012 (54.2 per cent). The data shows a major redistribution of national income away from wages and salaries towards profits (I could have shown the profit share graph as an alternative).

The Australian plot is more “ragged” because it is quarterly data, whereas the US graph is based on annual data.

What do these movements in the wage share mean?

To understand what the wage share is I summarise the answer from a recent quiz. For those not happy about simple algebra, don’t worry, I will make it clear in words when I get to the final point.

The share the workers get of GDP (National Income) is called the “wage share”. Their contribution to production is labour productivity.

The wage share in nominal GDP is expressed as the total wage bill as a percentage of nominal GDP. Economists differentiate between nominal GDP ($GDP), which is total output produced at market prices and real GDP (GDP), which is the actual physical equivalent of the nominal GDP.

To compute the wage share we need to consider total labour costs in production and the flow of production ($GDP) each period.

Employment (L) is a stock and is measured in persons (averaged over some period like a month or a quarter or a year.

The wage bill is a flow and is the product of total employment (L) and the average wage (w) prevailing at any point in time. The wage bill is the total labour costs in production per period, W.L

The wage share is the wage bill expressed as a proportion of $GDP, that is, (W.L)/$GDP.

We can actually break this down further to gain further insights. Labour productivity (LP) is the units of real GDP per person employed per period, that is, LP = GDP/L

It tells us what real output (GDP) each labour unit produces on average.

The real wage is the purchasing power equivalent on the nominal wage that workers get paid each period and is the ratio of the nominal wage (W) and the aggregate price level (P). The real wage (w) tells us what volume of real goods and services the nominal wage (W) will be able to command.

Nominal GDP ($GDP) can be written as P.GDP, where the P values the real physical output.

By substituting the expression for Nominal GDP (P.GDP) into the wage share measure ((W.L)/$GDP) we get:

Wage share = (W.L)/P.GDP

Which is equivalent to:

Wage share = (W/P).(L/GDP)

(L/GDP) is the inverse (reciprocal) of the labour productivity term (GDP/L).

An equivalent but more convenient measure of the wage share is: Wagee share = (W/P)/(GDP/L) – that is, the real wage (W/P) divided by labour productivity (GDP/L). The wage share is also equivalent to a concept that treasuries and central banks use called real unit labour cost (RULC).

It becomes obvious that the wage share will fall if the real wage grows more slowly than labour productivity. It could fall if the real wage falls faster than productivity falls. Either statement is correct.

The wage share in most nations was constant for a long time during the Post Second World period and this constancy was so marked that Kaldor (the Cambridge economist) termed it one of the great “stylised” facts in economics.

The reason that there was this constancy is because institutional structures introduced after the Second World War in the advanced nations as part of the peace-time full employment consensus ensured that real wages grew in line with productivity growth. This was the way that workers enjoyed non-inflationary increases in their living standards.

The productivity growth provided the “room” in the distribution system for workers to enjoy a greater command over real production and thus higher living standards without threatening inflation.

That all changed with the creeping onset of neo-liberalism in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Since that time, the neo-liberal assault on workers’ rights (trade union attacks; deregulation; privatisation; persistently high unemployment) has seen this nexus between real wages and labour productivity growth broken. So while real wages have been stagnant or growing modestly, this growth has been dwarfed by labour productivity growth.

The NYTs article says:

Conservative and liberal economists agree on many of the forces that have driven the wage share down. Corporate America’s push to outsource jobs – whether call-center jobs to India or factory jobs to China – has fattened corporate earnings, while holding down wages at home. New technologies have raised productivity and profits, while enabling companies to shed workers and slice payroll. Computers have replaced workers who tabulated numbers; robots have pushed aside many factory workers.

These trends have been apparent in most advanced nations but the reaction of the public sector has not been common. For example, the way the Norwegians have coped with these private sector trends has been to ensure growth in well-paid, secure (often part-time) jobs in the public sector providing a range of personal care, health and educational services.

Nations such as the US and Australia have sought to trash their public sectors. Over the last last 2-3 decades, many governments have implemented the supply-side agendas advocated by agencies such as the OECD (Jobs Study) and the IMF (structural adjustment), which were based on the neo-liberal myth that budget austerity and vast structural reforms would engender unprecedented growth in living standards.

The data doesn’t support the narrative.

These governments have variously introduced policies which allowed the destructive dynamics of the capitalist system to create an economic structure that was ultimately unsustainable. Once this instability began to manifest it was only a matter of time before the system imploded – as we are now seeing.

In Australia, the Federal government (aided and abetted by the state governments) helped this process in a number of ways: privatisation; outsourcing; pernicious welfare-to-work and industrial relations legislation; the National Competition Policy to name just a few of the ways.

The result is that it has become progressively harder for labour via trade unions to secure real wages growth in line with productivityThe next graph depicts the summary of this gap – the wage share – and shows how far it has fallen over the last two decades.

The NYTs article chose to quote a MIT academic as saying:

Some people think it’s a law that when productivity goes up, everybody benefits … There is no economic law that says technological progress has to benefit everybody or even most people. It’s possible that productivity can go up and the economic pie gets bigger, but the majority of people don’t share in that gain.

Which is a typical comment that you hear from economists and management theorists. There are no economic “laws”. The distribution of income is a social construct mediated by the institutions that a society creates and sustains.

The fact that the wage share was very much higher than now and stable for decades was because there was a collective will expressed through government policy that sought to mediate the raw outcomes that the capitalist market might produce.

The latter has no social values. We rely on government policy to express our values. The problem is that the top-end-of-town has used its political power and control of the media and other power sources to capture governments and reorient the policy agenda to suit their own narrow interests. This has clearly been at the expense of the “rest” of us. I don’t think the “rest” is 99 per cent – more like 80 per cent with an emphasis on the bottom 20 per cent.

So social institutions are the way we say that we want progress to be shared among all of us to reinforce the idea of a collective. Those institutions developed in the C20th because it was clear the alternative – with more power to the elites – was unsustainable and wars and revolutions proved that.

Social stability is influenced by the distribution of income, whichever way we want to express the latter. There is only so far that the elites can push before the rest of us will rebel and demand a fairer outcome.

While the notion of collective will has been usurped by the neo-liberal narrative that we are all in this as individuals and responsible for our own outcomes – the mainstream economics myth – the evidence is mounting that policies that support that narrative have dramatically failed.

Individuals are increasingly seeing that systemic constraints imposed on them by macroeconomic policy (aggregate demand constraints) render them powerless to participate in the benefits of productivity growth.

Everybody should benefit from productivity growth – that is what we call a society. It makes no sense to drive the train increasingly faster and leave an increasing proportion of the people stranded on the platform.

The shift in income distribution has also been a central factor in the crisis. In other words, the neo-liberals have been very successful at creating economies that were certain to fail, while enriching just a few.

The gap between labour productivity and real wages that increased over the last 2-3 decades in many nations represents profits and shows that during the neo-liberal years there was a dramatic redistribution of national income towards capital.

The question then arises: if the output per unit of labour input (labour productivity) is rising so strongly yet the capacity to purchase (the real wage) is lagging badly behind – how does economic growth which relies on growth in spending sustain itself? This is especially significant in the context of the increasing fiscal drag coming from the public surpluses in some nations (such as Australia) which squeezed purchasing power in the private sector in the latter half of the 1990s.

In the past, the dilemma of capitalism was that the firms had to keep real wages growing in line with productivity to ensure that the consumptions goods produced were sold. But in the recent period, capital has found a new way to accomplish this which allowed them to suppress real wages growth and pocket increasing shares of the national income produced as profits. Along the way, this munificence also manifested as the ridiculous executive pay deals that we have read about constantly over the last decade or so.

The neo-liberal trick was to foster the rise of “financial engineering” via widespread financial deregulation and a diminished oversight by responsible government prudential agencies (central banks etc).

The financial sector was able to garner the increasing profit share in national income and used it to pushed ever increasing debt onto the household sector. The capitalists found that they could sustain purchasing power and receive a bonus along the way in the form of interest payments.

This seemed to be a much better strategy than paying higher real wages. The household sector, already squeezed for liquidity by the move to fiscal austerity (for example, the Clinton surpluses in the US and the Costello surpluses in Australia) were enticed by the lower interest rates and the vehement marketing strategies of the financial engineers.

The financial planning industry fell prey to the urgency of capital to push as much debt as possible to as many people as possible to ensure the “profit gap” grew and the output was sold. And greed got the better of the industry as they sought to broaden the debt base. Riskier loans were created and eventually the relationship between capacity to pay and the size of the loan was stretched beyond any reasonable limit. These dynamics, of-course, led to the sub-prime crisis.

The problem with this strategy is that is was unsustainable. The only thing maintaining growth was the increasing credit which, of-course, left the nasty overhang – the precarious debt levels.

In the discussions the early Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) proponents had in the mid-1990s and after between ourselves via E-mail and various catch-ups, that these developments were going to blow-up.

It was obvious that this would eventually unwind as households and firms realised they had to restore some semblance of security to their balance sheets by resuming their saving.

Further, this increased precariousness of the household sector meant that small changes in interest rates and labour force status would now plunge them into insolvency much more quickly than ever before. Once defaults started then the triggers for global recession would fire and the malaise would spread quickly throughout the world.

I was often criticised in the 1990s and beyond by conservative economists and other neo-liberal types in the Australian media for “crying wolf”. They kept harping on the fact that wealth was rising so there was no problem. Even the RBA issued discussion papers advocating the “all is well” narrative. The mainstream profession introduced terms such as the “Great Moderation” to assuage our concerns.

Please read my blog – The Great Moderation myth – for more discussion on this point.

The chickens have come home in spades! The wealth has been severely diminished in the crisis but the nominal debt and the servicing commitments remain.

Apart from the anti-union legislation and other policy developments, the abandonment of full employment as a primary policy goal during this period has also been a major factor in the shift in wages and profits.

The NYTs article says:

MANY economists say the stubbornly high jobless rate and the declining power of labor unions are also important factors behind the declining wage share, reducing the leverage of workers to demand higher wages. Unions represent just 7 percent of workers in corporate America, one-quarter the level in the 1960s.

The abandonment of full employment and the deliberate creation of a persistently high pool of unemployment by governments has allowed the employers to increase their discrimination and stand hard against what union resistance has been able to survive the anti-union legislation.

These trends are endemic to the current crisis and unless they are reversed the crisis will persist and what growth there is will be undermined.

Several things have to happen if stable and sustainable growth is to return (I implicitly include here a raft of climate change policy developments – more about which another day).

The return to deficits is the first step in recovery. Budget deficits finance private savings and are required if the household balance sheets are to remain healthy. Almost every nation should be running larger deficits than they are now and be prepared to run these deficits indefinitely.

There is a huge private debt overhang that has to be eliminated before more stable private spending patterns will return.

Policy changes have to be made to ensure that real wages grow in proportion to labour productivity so that private spending levels can be maintained with sustainable levels of household and corporate debt. The household sector cannot dis-save for extended periods.

A whole host of financial market reforms are required to eliminate most of the financial markets, but that discussion is outside my ambit today. Please read the following blogs – Operational design arising from modern monetary theory and Asset bubbles and the conduct of banks for some further discussion on this topic.

In designing the policy framework that will sustain growth in employment and reduce labour underutilisation these tenets have to be central. It also means that the massive executive payouts both in the private and public sector (including universities) have to be stopped and more realistic distributional parameters (more widely sharing the income produced) have to be followed.

Obviously, I also consider an orderly dissolution of the Eurozone is required. But I will provide no further discussion on that today though.

Finally, the first thing national governments should do is to purchase all the labour that the private sector doesn’t want to use.

Conclusion

Until government realise that this trend cannot continue the problems will remain. Growth requires spending. There are only a few possibilities – consumption, investment, government and net exports.

If net exports are draining spending (that is, the nation is running a Current Account deficit), then the options narrow for which sectors will run deficits (spend more than they earn).

If the private domestic sector desires to spend less than it earns overall (that is, net save – saving greater than investment), then the options narrow to maintain growth narrow to one – the government sector has to run an on-going deficit.

If the government tries to run on-going surpluses (or even balanced budgets) then it is also signalling that it is happy that the private domestic sector is running persistent deficits (as flows) and the stock implications of that are simple – they will be accumulating increasing levels of indebtedness.

The problem with this strategy is that it is unsustainable and eventually the system will crash under the burden of the private debt.

The other option is that the government surplus desires are matched by surplus desires in the private domestic sector and the result is a major recession.

It is really that simple.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2013 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

“Incidentally, given the recent death of RSS creator and Internet activist Aaron Swartz it is worth noting that he had been charged with hacking into JSTOR in order to distribute the material on an open source basis. ”

There is no possible justification for monopoly protection of anything over five years old. If you can’t make a return in that period in a modern world then frankly somebody else should be given a go.

Locking ideas away like this is practically a crime against humanity.

Regarding:

“…the scale of our societies has become very screwed”

Does “screwed” mean something in Australia that it doesn’t mean in other places, or did you mean “skewed”?

I know auto-spellcheckers do this kind of thing as well…

Great article Bill!

I particularly find the the productivity vs real wage graph interesting as it depicts clearly how the elites have prospered at the expense of the average worker.

There was a good article in the Guardian yesterday and the first paragraph sums up the income distribution problem and that during this period of austerity where the average person struggles to find work and pay the bills, the elites have prospered.

http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/2013/jan/14/neoliberal-theory-economic-failure

“In 2012, the world’s 100 richest people became $241 billion richer. They are now worth $1.9 trillion: just a little less than the entire output of the United Kingdom.”

In order to save ourselves from the climate crisis, we must first reverse the catastrophic effects of neoliberal economic policy around the world. We have to vanquish it – intellectually, politically, morally, comprehensively. We can’t spend the money we need to spend or mobilize the real resources we need to mobilize in order to halt and reverse global warming if we continue to live as serfs under debt peonage to the Organization of Predator States. So. Revolution? Sure, but not necessarily the kind the word usually brings to mind.

In a lot of places, democracy is making a nice comeback. Mainly in Latin America, but there are stirrings in other places. Unfortunately, the U.S. has become one of the phoniest of nominal democracies, and the role of the U.S. in the world economy is such that this must change. I think the hinge of our fate will be student debt. I think the revolutionary demand that it be unilaterally cancelled will take hold and become unstoppable. This is the issue that gives us the best combination of moral high-ground and economic clarity. Anyone can see that millions upon millions of our kids have been defrauded outright by overpriced, predatory diploma mills. Worthless degrees shouldn’t have to be paid for. Degrees which have zero prospect of leading to a related professional-level job can be assumed to have been fraudulently marketed too. And to the extent that any amount student debt is judged to be legitimate, the government is ultimately responsible for the economic conditions that render it so.

Hire these kids or set them free – Let’s call it our “Job Guarantee”

Hire all those who want to work – Or be something that rhymes with “quirk”

The dimension that will decide the fate of capitalist societies and humanity as a whole is not the economic, despite the clear drive of the parasite elites to introduce neo-feudalism. It is not the ecological, despite neo-liberalism’s refusal to recognise the limits to growth on a finite planet or to allow proper action to avert climate destabilisation catastrophe. It is not the resource depletion crises, nor indeed a synergistic miasma of all these crises, and others. No, the crucial factor is the psychology of the ruling caste who have imposed neo-liberal ‘voodoo economics’ on the world, turning the 99% into economic zombies. These creatures, I think it is plain enough to see, are classic psychopaths. They display all the features-indifference to the fate of others, lack of human empathy, utter unscrupulousness and amorality, gigantic egomania etc. And they are insatiable, like the cancer, highly malignant, metastasising and undifferentiated in their features whether in the USA or about to put Myanmar under the boot, all in the name of ‘democracy’ and ‘our moral values’.

Thank you Bill, this is a very informative article.

I like to give a few aspects to consider. May it not be the abandonment of Central Banks from considering the growth of the system’s credit volume in their monetary decisions that led to all these problems?

Since about 30 years, Central Banks maintained their focus on the so called consumer price index as a base for their monetary policy, neglecting the increasing credit levels in the system. However, due to productivity gains, the consumer price index would have been negativ (lower prices) if Central Banks would not have maintained these inflationary policies which allowed the transfer of more and more wealth to the financial sector and as a consequence to the 1%. Had Central Banks focused on the massively increasing credit volume in the system (far in excess of economic growth), their policy would had to be much tighter. Lower consumer prices would have allowed the population to share in the economic benefits of increased productivity.

We may have to question the myth that low but always positive “inflation”, as measured by the consumer price index, is a positive for an economy but sound money may be more important for the economic system’s sustainability.

Whereas I do like your article, I feel that you miss this very important aspect in your analysis.

A short statement in regard to the present situation where you basically prescribe for governments to produce endless deficits and debt. This may very well work if the 1% can be kept within one’s borders. But you may miss the fact that the 1% and their capital are able to avoid to share or return part of their loot by changing the jurisdiction.

Just to give some more food for thought in relation to central banks.

1962, Lincoln printed 400 million dollars worth of Greenbacks (the exact amount being $449,338,902), money that he delegated to be created, a debt-free and interest-free money to finance the War. It served as legal tender for all debts, public and private. He printed it, paid it to the soldiers, to the U.S. Civil Service employees, and bought supplies for war.

Shortly after that happened, “The London Times” printed the following: “If that mischievous financial policy, which had its origin in the North American Republic, should become indurated down to a fixture, then that Government will furnish its own money without cost. It will pay off debts and be without a debt. It will have all the money necessary to carry on its commerce. It will become prosperous beyond precedent in the history of the civilized governments of the world. The brains and the wealth of all countries will go to North America. That government must be destroyed, or it will destroy every monarchy on the globe.”

The Bankers obviously understood. The only thing, I repeat, the only thing that is a threat to their power is sovereign governments printing interest-free and debt-free paper money. They know it would break the power of the international Bankers.

On April 14, 1865, Abraham Lincoln was shot dead by Wilkes Booth.

After the end of the civil war, Congress revoked the Greenback Law and enacted, in its place, the National Banking Act. The national banks were to be privately owned and the national bank notes they issued were to be interest bearing. The Act also provided that the Greenbacks should be retired from circulation as soon as they came back to the Treasury in payment of taxes.

Linus Huber,

I believe your observation about the financialisation and growth of private debt in the system is correct – this was one of root causes of the current instability. However the dismantling of the current system or simply refusal of Central Banks to provide enough reserves to commercial banks would move us back to the late 19th century – a period of even more volatility. High and unstable interest rates would follow the “sound money” policy – leading to throttling of productive investment and depletting the “revolving fund of finance”. This may look promising from the environmentalist perspective but is not a solution for the future because the technological progress which can provide environmentally sustainable solutions in the long run would also slow down.

The hole in aggregate demand which needs to be plugged to make the system more stable in the long run is hoarding of financial assets by the richest. We (living in the Western countries) need to slap taxes on the stock of financial capital and other unproductive wealth – the solution advocated by Kalecki. We need to partially dismantle the financial sector and shrink it so that it plays a subservant role to the productive economy. This has nothing to do with the correct policy in the short run that is to increase budget deficits so that the productive capacities in the industries we want to develop do not lay idle and accomodate deleveraging (the hoard of financial assets already exists but it is counter-balanced by a stock of private debt mainly related to non-productive activities, that stock of private debt needs to be replaced by the public liabilities). We need to implement the Job Guarantee to energise the workforce. We also need to keep in mind that the original Kaleckian policy was calibrated for a different monetary system environment (where remnants of the gold standard were still in place).

An alternative is going cold-turkey that is austerity. Austerity cannot be augmented by the ongoing confiscation of financial assets of the richest as such a policy has a different time scale.

Please compare the economic results of the policy implemented in China to what’s currently going on in Europe especially on the unemployment front. It is obvious that the current growth trend in Asia is unsustainable in the long run but the Chinese are bootstrapping the process of global economic transformation. They are investing enough real resources in developing, commercialising new technologies (or simply transferring ther knowledge from the West, what is good) so that they are on the track of becoming global leaders of a balanced and sustainable economy of the second half of the 21th century.

While Europe is closing its nuclear reactors and dismantling the productive industry the Chinese invest heavily in commercialising the thorium cycle. They are already a global leader in solar panels. Such massive research projects can only be run and financed by the state (with some contribution from the private sector).

Austerity is a road to nowhere. Our only chance as the humanity is quickening the technological progress otherwise the environmental constraints will destroy the Western civilisation. The Europeans must ditch the toxic way of thinking tested so thoroughly in the early 1930s and resurrected as “neo-liberalism”. They probably won’t do that and they will be the losers. In the future the rich Chinese will visit the impoverished Euro-Disneyland to see the castles, churches and (especially) medieval universities where the dumb ideology of civilisational suicide assisted by the rich was developed in the late 20th century.

Similar things may be happening in other countries, but I’m sure America would lead the pack. Britain might give us a run, but I think we are #1 in increasing inequality.

Out of interest,

Does anyone know what the origin of the word neoliberal is?

The first I heard it was watching one of Bill’s video peices where he says “I call them neoliberals.”

Is this another example of people pinching MMT’s (or Bill’s) ideas?

Bill, if you did invent it, please put us out of our misery.

Kind Regards

Dear CharlesJ (at 2013/01/16 at 9:28)

You can find a brief introduction to the term neo-liberalism here – http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neoliberalism

You will see it predates me by many years.

best wishes

bill

Bill,

Just read the wikipedia description of neoliberalism – they were indeed a very conflicted bunch.

Thanks

Dear Prof. Mitchell,

You’ve written some excellent articles over the years. To me, however, this is perhaps one of the best, if not the best, of them all.

And it is particularly valuable because, other than yourself and perhaps half a dozen others, nobody in Australia seems to have to guts to deal with inequality.

Congratulations and thanks for your efforts in educating us.

——–

As I am particularly interested in Australian data, I’d like to ask if the Australian data from the table and chart are before or after taxes. I assume you are using ATO data.

@ Adam

Thank you for your qualified reply. I enjoy to exchange of views with someone who has a conviction.

Let me try to reply to a few aspects that may be a problem in your theorie.

You cannot put the feet of the very rich to the fire in today’s world where capital can move very quickly from one economic area to another. It works for the normal citizen as he does not have the financial capacity to employ the required know-how on protecting his savings but not for the elephants on the floor. We are certainly aware that restrictions in the move of capital are gaining ground at an increasing speed but it might be similar to warfare, as soon as a new weapon has been developed the defence catches up extremely fast to eliminate the threat.

What does this mean in the present context? The heavy hitters will decide on which policies are acceptable in a sense that they will increasingly force certain policies on governments or withdraw the capital from the concerned economic area. Of course, this is a completely unsatisfactory situation but it can only be resolved on a worldwide basis.

I completely agree with you that the financial sector has to be dismantled to a certain degree and made a part of the economy that serves the populace. Where we might have a different view is in the mechanism to achieve this task. The idea to simply introduce a jobs guarantee does not really resolve the problem of the high level of credit within the economy but may even stimulate the accumulation of more debt. We all know that the money supply basically consists of base money and credit volume in the system. In my humble opinion, we should replace part of the credit volume with base money but under avoidance of the financial sector and channelling the funds directly to the individual citizen who would be obliged to reduce his/her debt accordingly (those without debt are free to employ the funds). This would reduce the credit volume in the system but still be fair as it is a “per head policy” that benefits all members of the population equally, even those without debt. Present policy hurts savers and people who chose a sustainable life style while benefitting those that took on debt. That means, bad behaviour is rewarded which does not represent a positiv for society at large. In addition, as everyone would be treated nominally equal, the rich will get in relation to their assets much less benefits.

Of course the above policy needs to be accompanied by much different rules in the area of credit creation by the financial industry. E.g. complete stop of saving an institution. Requirement for the declaration of the available risk capital of each institution using market valuations of assets (no modelling). This is required that a bank’s creditability is easily recognized by the saver. Stop of saver’s guarantee, so that those declarations become a deciding factor when selecting the service of a bank. Obligating Central Banks to ensure that credit creation does not exceed economic growth. etc.

You mention China and explain that they have been successful. I am afraid that you might be right but when looking at it from a philosophical point of view, we can find policies similar to China’s emerging more and more. In times past, this economic model was characterized as fascism. It destroys more and more the individual’s freedom and increases the state’s influence in the economy to the detriment of real creativity. I do believe that we still possess a considerable higher degree in our capacity to create and the chinese modell is certainly suspect with regard to sustainability.

I know that the subject is so large and any explanation simply touches on some of the aspects but seldom on the whole. But please, do counter my arguments as often as possible so that I am forced to think things throu and that teaches me to explain myself better. Thanks again.

Linus Huber,

Let me respond briefly as you raise a few interesting points.

1. There is a political dimension and economic dimension of the issues you have mentioned. I am quite pessimistic about the European politics. In my opinion the future of Western Europe is stagnation. I believe that it is exactly the extreme neoliberal policy dictated by the EU and especially austerity what may lead to the rise of fascism in Central Europe (e.g. in Hungary). The majority of European people have been so thorougly brainwashed that they accept that economic conditions must keep deteriorating. Even the unemployed believe they have to suffer – nobody has any hope. They see no alternative. Fascism rose in Europe after WW1 in similar conditions.

2. State capitalism is not fascism. The problem with nazism was not that there was no creativity. Just look at the technological progress made by the German industry at that time. The problem was that Hitler committed a genocide on Jews and Gypsies and mass-murdered Slavs. The problem was that he started the war which destroyed Germany. Just because state capitalism looks similar to Nazi economic model doesn’t mean that the neoliberal model better safeguards individual liberties.This is false. It does not guarantee the right to employment which is a basic human right. It is the failure of the neoliberal model what may lead already brainwashed people to again chose fascism.

3. It is much easier for the government to spend rather than to confiscate – once the people understand that government spending is NOT fiscally constrained (it is only constrained by the real capacities of the economy), Job Guarantee will establish a new baseline and lead to the profound change in the social conscioussness. Right to employment is one of the basic human rights as recognised by the United Nations. This moral truth has been artificially obscured using the pseudo-scientific explanations of the phenomenon of involuntary unemployment.

4. There is no problem of rising public debt used for financing Job Guarantee policy – the issue has been explained thoroughly by prof Mitchell and I am not going to repeat his arguments. To me there might be a system stability issue but not with the size of the stock of public debt but with the total size of the stock of the savings (financial assets). We both agree that financialisation should be reversed. MMT advocates zero interest rates policy what would render excessive saving (hoarding) virtually useless as a tool for the rich to make more money. Yes in that sense it does not reward “savers”. But why should the “savers” be rewarded? I don’t see any moral arguments for encouraging collecting pieces of metal, paper or numbers in the bank’s database. I see a lot of value in not wasting natural real resources but this is another issue. It is precisely rewarding “savers” what makes the system unstable. What is the special social role of increased private saving? MMT dispels the myth of economic benefits of increased saving propensity (under normal circumstances). It is just a number, a parameter and the rest of the system should accomodate it. If you want more arguments – please read prof. Kazimierz Laski’s “Do Increased Private Saving Rates Spur Economic Growth?” available as a PDF.

@ Adam

I need to correct one of your perceptions, namely that I am of neo-liberal persuasion. When looking at my arguments, I thought, that you would recognize this not to be the case. I despise the neo-liberal idea that mainly protects the present elite’s position whether it be in the field of economic actors or political power.

What disturbs me most about your ideas is namely the fact that you try to pursue kind of a statist arrangement where power is mainly with the government to the complete exclusion of individual rights. A government is in itself a rather powerful structure and in my opinion, we should restrict institutionalized power and not increase it. By now already, we suffer considerably from the increased interference by governments in our affairs as we step by step discover that many a policy is not sustainable at all. As we all know, power corrupts and absolute power corrupts to the core. It is my conviction that each and every citizen must carry some burden and responsibility for a well functioning democracy that those responsibilities cannot be delegated to the state in order to maintain one’s self-respect, personal freedom, a civilized way of life, accountability and peace with each other in external as well as in internal affairs.

The primary purpose of state capitalism is not to produce wealth but to ensure that wealth creation does not threaten the ruling elite’s political power. Even a war will justify the objective to stay in power in such a situation. When looking at it from this angle, one might conclude that you probably stand closer to the neo-liberal idea than me.

You quote “It does not guarantee the right to employment which is a basic human right.”

If the state proves to be better than the private sector in finding economically reasonable projects that will create jobs, I would be all for it. But I do have my doubts that these thugs that hang around in those offices of power and feel that they keep the well-being of the population in their hands, will be wiser and/or better equipped than an individual entrepreneur who based on his natural and analytical capacity to sniff out opportunities to size and conclude successfully. I know that you will probably dislike me for this statement but I have to say that if something smells, feels und looks like communism, it most probably is exactly that.

The economies deteriorate slowly but consistently due to the fact that the economic elite was able to influence public policy in their favor over decades now. It is necessary to dismantle this unholy alliance and to free us from these increasingly more and more damaging and unsustainable policies. Having said all this, I of course agree that the state is responsible to ensure that each of their citizens is provided with the basics for survival (food, clothing, shelter and some degree of health care).

I do not have a problem with an interest rate of 0% as long as we do not inflate the money supply at the same time. Otherwise it is a policy of theft. You state that it is ok to basically steal from those who saved some money. Well, what is one’s individual saving (talking about an average person) but one’s past work. It is in the nature of a human being to save some of his efforts for consumption at a future point in time when in need or when misfortune occurs. When I save 100 hours of work today, why then should I receive in 10 years from now only 60 hours in return? Is this really the society we like to live in? Doesn’t this kind of policy produce exactly these problems that we face today, namely a society of speculators and of an increasingly volatile and unstable currency system?

I have checked out some parts of your references and must conclude that the statistics used in such work often refer simply to experiences after WW2. In my opinion, such analytical work has very limited validity as it is focused simply on one single long term economic cycle.

I do not have a problem with an interest rate of 0% as long as we do not inflate the money supply at the same time. Otherwise it is a policy of theft.

Linus. This statement is insane.

Creating credit, issuing money is not theft.

Be logical! All money had to be issued at one time. By your logic, it is all “theft”.

Inflating “the money supply” NEED NOT cause price-inflation. Ever. What looks to you & many others to be an “obvious” truth – is in fact wrong. Spectacularly wrong. Insanely wrong. Try to make a logical argument for it, and we will pick out the gigantic holes. MMT & the JG would be the strongest anti-inflation policy ever – I think the academics tend to grossly underestimate this with academic understatements.

The JG – administered say by a 12 year old of average intelligence and morality – decreases state power, decreases centralization, is libertarian, increases individual rights, is anti-statist the way you would approve. The state is the only one that can employ everybody – because it is the one who disemploys them in the first place! Individual entrepreneurs CANNOT do it. Even if they wanted to do it, they couldn’t do it! It ain’t their responsibility, it ain’t in their power. They didn’t cause unemployment. The state did.

As always, your implicit theory of money is what is at fault. Money ain’t what you think it is. (As further proven by using the atrocious oxymoron “debt-free money”. Lincoln did not create debt-free money. Interest-free doesn’t mean debt free. Nobody can create debt-free money. Money. IS. Debt. Did Lincoln create debt-free debt?

As I have said before, Bill cannot write a blog that covers everything in economics every day. You can find all the themes you that resonate to you in MMT – but aufgehoben, resolved into a consistent whole, not an eclectic mass of conflicting theories. MMT addresses your concerns. It agrees with what you are saying about private credit and inflation etc – but it puts it all together in a consistent manner, not belittling gigantic problems and magnifying microscopic ones.

Sorry for not having looked at or responded some of your earlier replies to me til now- very busy. The horribly common idea of the government (or anyone else) printing money out of nowhere being theft roused me. What is being stolen, pray tell?

“This statement is insane.”

No, it comes straight from the von Mises blog. It is just confusing stocks and flows.

@ The Some Guy and Adam

Thanks for your reply.

Well, I may have given you an easy target when I did not express myself more specifically above. When prices increase due to inflationary monetary policy, it is for me theft as I am robbed of my purchasing power. We do not have stable prices but a continuous loss of purchasing power since 100 years so that everyone got used to this continuous depreciation of currencies. The fact that we got used to it, does not make it right.

You are correct that the increase of money supply does not necessarily produce higher prices. It depends on base money supply plus the volume of credit in the system. We did not have raging inflation from 2003 until 2007 but the total money supply (base plus credit) expanded at a rate vastly in excess of economic growth. One cannot control where the money will flow to but it distorts the prices within the economy, resulting in negative consequences. In addition there can be lags in the effectiveness of some measures which often leads to questionable analysis.

With reference to the times article in connection with Lincoln, it was never meant to prove any of my believes but was simply to motivate readers to consider how people at that time were thinking about the power of the money issuing authority.

“The JG – administered say by a 12 year old of average intelligence and morality – decreases state power, decreases centralization, is libertarian, increases individual rights, is anti-statist the way you would approve.”

How exactly is this what you suggest going to work? You do not give any indications about the mechanics and procedures etc.? Maybe I suffer from lack of imagination but I cannot (within the present political system) recognize how this should really work out. To me it looks like another of those government schemes without any real benefit to society except of course for those enjoying the benefits of the scheme. You have to find economically reasonable projects etc. etc. Not an easy task for those people in government. Or is the idea to simply force the unemployed onto large firms. Answer me to the pertinent and simple questions, please. If, as you state, this system would reduce the state’s power and ensure more freedom, well, you will certainly find me more then ready to listen.

Linus Huber,

If you can stomach my engineering (not economic) jargon… here it goes.

Inflation is a process of a continous increase of both wages and prices levels. Austrian economists redefine it an an increase in the stock of money (or currency and credit). I simply refuse to use that definition because it is an element of mental manipulation, a ‘new-speak” term as brilliantly described by G. Orwell. Unless inflation (dP/dt, the derivative of the averaged price level) is in high double digits (then it may be called hyperinflation) it does not affect people living off their wages or living off indexed state pensions. It only decreases the purchasing power of the stock of savings stored in currency. The phenomenon you described as “when prices increase due to inflationary monetary policy, it is for me theft as I am robbed of my purchasing power” only affects the stocks not the flows as the inflows rese with outflows. The loss of purchasing power is related to rising relative prices (P/w). I am not aware of that phenomenon occurring anywhere now due to inflation. It is true that the deflationary policies engineered in Greece and other EU countries have a goal of decreasing the “w”. This is where “people are robbed of their purchasing power” but by deflation, not by inflation (“w” – the wages are set locally but “P” – the prices of consumer goods are pretty much the same across the whole EU).

I don’t have a problem with a moderate level of inflation. I lived in an Central European country with a moderate level of inflation (in the early 1990s) and it did not do any harm to me or to the economy. The infamous “cooling off” enginered by mad monetarist in the late 1990s in the name of “fighting inflation” did a lot of REAL harm – the unemployment rate reached 20% at some point but what’s going on in Greece and Spain now looks even worse.

To fight off inflation as a saver you have a few tools – bank deposits often offer real positive interest rates on long-term deposits. In some countries TIPS (Treasury Inflation Protected Securities) bonds are available as a saving vehicle. Nobody can guarantee that the purchasing power of the currency will remain absolutely constant over a long period of time. This is NOT a part of the “social contract”. The stability of prices in the medium term (weeks/months) is a part of the contract. MMT addresses this issue – you can find multiple references to this issue here, on prof Mitchell’s blog.

Finally if we want to analyse the correlation between the stock of currency and credit and the price level, it is the growth of the quantity of money (dM/dt) what generates an extra flow adding up to the aggregate demand, affecting the price level. It is NOT the absolute size of the stock (M). That’s why during the bubble years the West experienced inflationary pressures and state budgets went into surpluses. Now we are in debt deleveraging phase and private sector tries to reduce its indebtness (dL/dt < 0). That negative flow (flow going to a sink) must be compensated by rising budget deficits or the system settles at a very low level of capacity utilisation and high unemployment (and saving desires of some agents are frustrated). If this is what the Austrians want (they call it a "creative destruction"), they should tell these 50% of young people in Spain who are jobless that individuals need to be sacrificed like sheep on the altair of the praxeological cult invented by von Mises and von Hayek . It was all about the individual liberty at the beginning…

@Some Guy, you’re completely wrong about debt free money beipng an oxymoron. Financially sovereign countries can mint or print money with or without a corresponding increase in debt.

“Financially sovereign countries can mint or print money with or without a corresponding increase in debt.”

Depends how you define debt.

Technically financially sovereign countries don’t have really have debt if the instruments are in their own currency. They have mere liabilities that can be eliminated at the touch of a computer button.

So if you define debt as stuff that requires expenditure of real resources to repay then few financial sovereign countries have debt. So its all ‘debt free money’ in that sense. If you define it to include those liabilities then the currency is also ‘debt’.

For me the way people describe these instruments is designed specifically to push a political agenda. It doesn’t help the analysis.

“it does not affect people living off their wages or living off indexed state pensions.”

It doesn’t affect trading businesses either who simply mark up their costs with the required profit. Nor does it affect those exploiting real assets either – again because they just mark up their costs with the required profit.

Not if you stick to sensible definitions.

You could, at a stretch, say that money it owes to itself isn’t really debt (though this would be very much a minority view) but there’s no way you can credibly deny the money it owes to others is debt. There are lots of debts that can be eliminated (by paying) at the touch of a computer button.

And if you define icecream as stuff that requires expenditure of real resources to repay then few finincial sovereign countries have icecream. But that’s not what icecream is, nor what debt is.

Debt is in the currency, but fiat currencies are not themselves debt.

Inventing strange new definitions of commonly used words doesn’t help the analysis, it makes you look like a lunatic fringe conspiracy theorist. We can’t properly explain why commonly held beliefs are wrong if we distort words to mean something that they’re normally intended to mean. Even Bill’s claiming that a oneoff price increase isn’t inflation negatively affects his credibility, for everyone else says it is. The mainstream makes a distinction between headline and underlying inflation (with a oneoff price increase affecting only the former), but having a nonstandard definition of inflation is a favourite tactic of the Austrian School.

“Debt is in the currency, but fiat currencies are not themselves debt.”

Yes it is. That a liability has no means of paying itself off other than by another version of that liability doesn’t make it any less of a debt.

A debt is owed to somebody. We pay for things in a monetary economy by swapping debts with each other. That’s how it works. You create a debt by taking delivery of goods and you relieve yourself of that debt by swapping it for a debt you happen to have with the central bank that is acceptable to the recipient. That recovers your own debt allowing you to eliminate it from your balance sheet.

The use of the word debt is pejorative and designed to mislead. It should be avoided – just like the word ‘money’.

You have liabilities, you have interest bearing liabilities and you have time limited interest bearing liabilities. Analyse with those and the moral and religious undertones are avoided.

Neil Wilson, I’ve got a dollar in my pocket. Its currency, but its an asset, not a liability.

“Neil Wilson, I’ve got a dollar in my pocket. Its currency, but its an asset, not a liability.”

Jeez Aidan I didn’t think I’d have to explain basic accountancy to you. OK I’ll rewrite it from the other side of the balance sheet.

It’s an asset to you because it is a liability of the issuer.

Therefore when you buy something from the grocer, the grocer is happy to swap the asset of your debt to him for an asset of a debt from the central bank.

You then get back the asset of the debt you created which brings it together with the liability of the debt you already held and that annihilates the debt – much as matter and anti-matter eliminate each other.

So we go around swapping stuff we’re owed in exchange for other stuff.

Neil Wilson, I’ve got a dollar in my pocket. Its currency, but its an asset, not a liability.

This is exactly the point of a basic MMT insight about net financial assets of consolidated nongovernment in aggregate.

That dollar as an asset in a private sector “pocket” (account ledger) has its corresponding liability on the public sector’s books. This is a “vertical” relationship of public-private that allows for the creation of net financial assets of consolidated nongovernment in aggregate (NFA). All private sector credit is offset by debt in the private sector (“horizontally”) so that the closed “horizontal” sectoral net is zero. Govt issuance of its own liabilities as tax credits for the private sector “opens” the system by increasing ∆NFA through fiscal deficits (flow) and decreasing ∆NFA through fiscal surpluses (flow). Flows alter stocks over a period.

As Neil and the MMT economists say, it’s all in the accounting. It’s very difficult to understand this without paying attention to the accounting and its implications.

Neil Wilson, you have let basic accounting conventions (where everything has to add up to zero) shield you from the truth.

The reason the dollar’s an asset to me is nothing to do with the liability of the issuer. It’s because it’s legal tender (legally required to be used to settle debts) and because there’s demand for it (which is ultimately due to taxation).

“It’s because it’s legal tender (legally required to be used to settle debts) and because there’s demand for it (which is ultimately due to taxation).”

Legal tender has little or nothing to do with it. That is a very narrow definition designed to prevent infinite regress in a court of law. And taxation is the same argument I put forward – the person that created the debt gets the circulating asset part back swapping assets and liabilities.

Which explains why taxation and spending have to be active actions. You can see it has having to supply the circulating assets (and hold the liability) *and* create the tax bill liabilities (and hold the asset) so that people seek out the circulating asset allowing them to swap it for the tax bill asset. You then get the tax bill asset annihilating the tax bill, and the taxation authority gets the circulating asset annihilating the liability they hold.

The point being that there is nothing real at the end of the rainbow. It’s just swapping nominal assets and liabilities around in a system that ultimately sums to zero.

Aidan says:Saturday, January 19, 2013 at 11:15 “Neil Wilson, you have let basic accounting conventions (where everything has to add up to zero) shield you from the truth”

Money is an idea not a thing. Sub-human species cannot handle it cognitively; it is worthless to them. Moeny is a human social construct that has no meaning out of context. Modern money serves at least four main purposes: 1) unit of account, 2) medium of exchange, 3) store of value, and 4) method of deferred payment. Notice that “unit of account” is listed first, in that money as an idea that gets its meaning from context constitutes information. Unless the accounting is taken into account, noise overshadows the signal. Those notes and coins in your pocket are much more than tokens representing purchasing power in the context of a particular currency zone and having exchange value across currency zones, although they are that, too. But chiefly, they are packets of information that have significance in context.