I grew up in a society where collective will was at the forefront and it…

New President but old narrative

Obviously the big deal today is the US election result. My distant (being in Australia) and relatively disinterested (a pox on all of them) view is that the conservatives (GOP) should continue to foster links with the Tea Party and particularly senators and would-be senators who think women have a choice in rape so that the party continues to lose traction with the changing demography in the US and march off into oblivion. The other conservatives (the donkeys) won because the motor car industry is still operating and because the elephants in the room were so bad. The commentary on Australian TV today (one of my computers in my office is following the results even though I am “disinterested” :-]) has become obsessed with the “fiscal cliff” with all the experts appearing demonstrating their vast ignorance about macroeconomics. An ex-federal Opposition leader (failed) in Australia (and a former professor of economics) just said that the US deficit and debt is reaching European proportions, which tells you that he is either deliberately choosing to mislead the viewers or doesn’t know the difference between a currency-issuer (the US) and a currency-user (Eurozone nations). The election result will probably not change much. The political impasse is saving the US economy at present – the deficit is still flowing each day and supporting some growth.

In all the discussions about the fiscal cliff the reality facing the US seems to be ignored. The conservative fringe still propagate the myth that the persistent unemployment is a structural problem and cutting aggregate spending will not impact on that problem.

They promote socio-pathological policies denying the unemployed continuing federal income support and claim that more incentives to work have to be forced on the unemployed.

The evidence does not support those viewpoints.

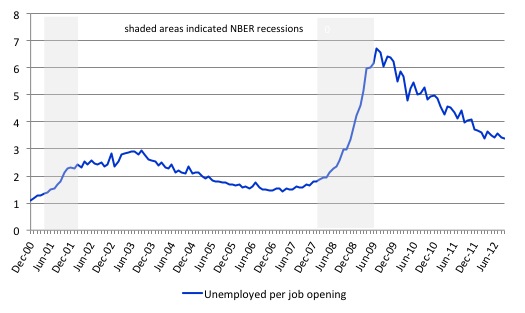

The following graph utilises the US JOLTS database, the latest edition (up to September 2012) being published yesterday (November 6, 2012). It shows the total number of unemployed per job opening (non-farm and seasonally adjusted) and thus gives a measure of how strong the demand-side of the labour market (job openings) is relative to the number of people seeking work (the unemployed).

In 2010, the US Bureau of Labor Statistics described the data at that point in this way:

When the recession began in December 2007, there were 1.8 unemployed persons per job opening. The ratio rose to a high of 6.2 unemployed persons per open job, more than twice the highest ratio seen since the JOLTS series began … From the high of 6.2 unemployed persons per job opening in November 2009, the ratio fell to 5.0 in June 2010.

Since 2010, the ratio has been improving steadily as employment growth continues but it still has a long way to go before it reaches the pre-crisis levels where, at its lowest point (March 2007) there were 1.4 unemployed person per job opening.

Labour markets typically behave over the business cycle in an asymmetric manner as can be seen from this perspective. The deterioration was sharp and rapid. The recovery is much slower and is all the more slow because of the bungling economic management of the current President and the US Congress.

The unemployed cannot search for jobs that are not there! This is exactly what happens when aggregate demand falls and job openings dry up. At present, according to the JOLTS data, there are 3.4 unemployed persons per job opening.

That requires a substantial up-tick in employment growth and that should be the focus of the US government in the coming months. Instead we will be flooded with elephants and donkeys talking about saving the US from a Greek-like demise and the need to restore individual incentive etc.

When there are not enough jobs being created what individuals do is largely irrelevant from a macroeconomics perspective. A hard demand constraint on the labour market rules!

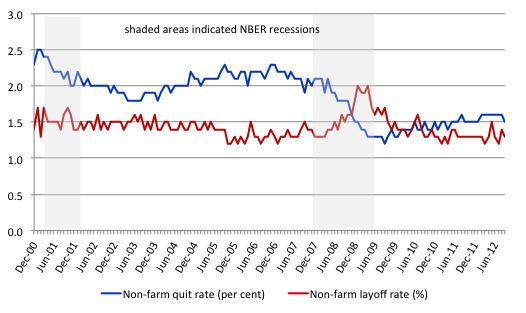

Another way of seeing how the job flows tell us about the direction of change is to compare layoffs with quits.

The mainstream textbook treatment of the labour market, which students around the world are forced to learn as if it describes the real world, leads to the prediction that fluctuations in unemployment reflect supply-side changes arising from imperfect information or reflecting changing preferences between leisure and work.

Please read my blog – Even the most simple facts contradict the neo-liberal arguments – for more detailed discussion on the theoretical approach that leads to this conception.

The textbook model claims that the real wage is determined in the labour market at the intersection of the labour demand and the labour supply functions. The equilibrium employment level is constructed as full employment because it suggests that every firm who wants to employ at that real wage can find workers who are willing to work and every worker who is willing to work at that real wage can find an employer willing to employ them. Frictional unemployment is easily derived from the Classical labour market representation, as is voluntary unemployment.

Holding technology constant, all changes in employment (and hence unemployment) are driven by labour supply shifts. There have been many articles written by key mainstream economists (such as Milton Friedman) that argue that business cycles are driven by labour supply shifts.

The essence of all these supply shift stories is that quits are constructed as being countercyclical – that is, rise when the economy is in decline and vice-versa – despite all evidence to the contrary.

Lester Thurow in his marvellous book from 1983 – Dangerous Currents challenged this view, asking:

… why do quits rise in booms and fall in recessions? If recessions are due to informational mistakes, quits should rise in recessions and fall in booms, just the reverse of what happens in the real world.

So one of the most simple ways to reject the mainstream macroeconomics conception of the labour market, which constructs unemployment as being a supply-side phenomenon and hence quits as being countercyclical is to look at the quit rate.

The US Bureau of Labour Market JOLTS database includes estimates of the quit rate. The following graph shows in a compelling way that the quit rate (non-farm quits as a percent of total seasonally-adjusted non-farm employment) behaves in a cyclical fashion as we would expect – that is, it rises when times are good and falls when times are bad. Many studies have demonstrated this phenomenon for several countries where decent data is available.

Further, the layoff and discharges rate also published in the BLS JOLTS database which reflects the demand-side of the labour market is shown (in red) to be firmly counter-cyclical as we would expect. Firms layoff workers when there is deficient aggregate demand and hire again when sales pick-up. Again this is contrary to the orthodox logic.

The clear significance of this behaviour is that the orthodox explanation of unemployment is not supported by empirical reality.

In relation to the fiscal cliff debate we note two things about the behaviour of the quit rate. First, it is now above the layoff rate but only just. Second, the recovery in the quit rate, which reflects the increasing mobility that is possible in a growing labour market when jobs are being created in greater numbers, is very slow in this cycle. The layoff rate is back to its steady level but the growth in job openings is not strong enough to elicit the sort of mobility that we see present before the crisis.

To see the challenge ahead for the US, I have done some simulations based on a rule of thumb based on Okun’s Law. The so-called Okun’s Law arithmetic allows us to estimate the deficiency in GDP growth which leads to rising unemployment rates.

Okun’s Law (it was in fact a statistically estimated relationship with stochastic variation) is the relationship that links the percentage deviation in real GDP growth from potential to the percentage change in the unemployment rate.

The algebra involved in the conceptualisation of this “law” can be manipulated to come up with a “rule of thumb” which is a way of making guesses about the evolution of the unemployment rate based on real output forecasts.

What is a rule of thumb? It is not a rigid exact relationship. There are no such relationships in social sciences. It is rather a recognition that labour market and product market aggregates are intrinsically linked by construction and behaviour and over time allow us to make guesses about the future of one variable based on the evolution (hypothesised) of other variables.

Here is a simple explanation of this rule of thumb. We can relate the major output and labour-force aggregates to form expectations about changes in the aggregate unemployment rate based on output growth rates. A series of accounting identities underpins Okun’s Law and helps us, in part, to understand why unemployment rates have risen. Take the following output accounting statement (which is true by definition and not a matter of opinion or conjecture):

(1) Y = LP*(1-UR)LH

where Y is real Gross Domestic Product, LP is labour productivity in persons (that is, real output per unit of labour), H is the average number of hours worked per period, UR is the aggregate unemployment rate, and L is the labour-force. So (1-UR) is the employment rate, by definition.

Equation (1) just tells us the obvious – that total output produced in a period is equal to total labour input [(1-UR)LH] times the amount of output each unit of labour input produces (LP) .

Using some simple calculus you can convert Equation (1) into an approximate dynamic equation expressing percentage growth rates, which in turn, provides a simple benchmark to estimate, for given labour-force and labour productivity growth rates, the increase in output required to achieve a desired unemployment rate.

Accordingly, with small letters indicating percentage growth rates and assuming that the hours worked is more or less constant, we get:

(2) y = lp + (1 – ur) + lf

Re-arranging Equation (2) to express it in a way that allows us to achieve our aim (re-arranging just means taking and adding things to both sides of the equation):

(3) ur = 1 + lp + lf – y

Equation (3) provides the approximate rule of thumb that if GDP growth (increasing demand for labour) is greater than the sum of labour productivity (reducing labour requirements) and labour-force growth (with participation rates constant), the unemployment rate falls. However, if the sum of labour-force growth and labour productivity growth outstrips GDP growth, then the unemployment rate rises.

The Okun framework allows us to make predictions about changes in the unemployment rate given the rate of growth of GDP. Simply stated, labour productivity growth reduces the amount of labour required for each unit of output, while labour-force growth increases the number of jobs that have to be created if unemployment is to remain unchanged. So both growth rates place upward pressure on the unemployment rate.

If GDP growth is strong enough, the economy can absorb the labour supply and labour productivity growth. For the unemployment rate to be constant, real GDP growth has to equal the sum of labour-force growth and labour productivity growth. We can call this the required rate of GDP growth. Any better will lead to a falling unemployment rate, while any deficiencies in the required rate will see the unemployment rate rising.

The Okun framework is an approximate relationship because cyclical movements in labour productivity (changes in hoarding) and the labour-force participation rates can modify the relationships in the short-run. But it should provide reasonable estimates of what will happen once all the cyclically-sensitive components of the economy return to more usual values.

When an economy starts to grow again the labour force growth in the short-run will be more brisk than it will be once growth is sustained which will tend to mean our rule of thumb will overestimate the decline in the unemployment rate in the short-term although over a longer period the rule of thumb will be more accurate.

The US Bureau of Labor Statistics data shows that labour force growth varies considerably over a cycle. In January 2009, at the peak of the last cycle, labour force growth was 1.95 per cent per annum. It is currently at 1 per cent per annum. At the depth of the downturn the labour force contracted as hidden unemployment soared due to a lack of jobs.

If the US economy grows more robustly then the labour force will start expanding towards that higher figure.

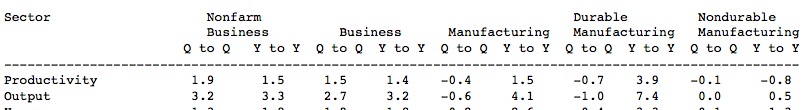

The US Bureau of Labor Statistics publishes productivity estimates for the US economy. The following table snippet is taken from their Table A September 2012 release.

Labour productivity growth is also highly cyclical (due to hoarding and other factors). At present the non-farm business sector productivity is growing at around 1.5 per cent per annum.

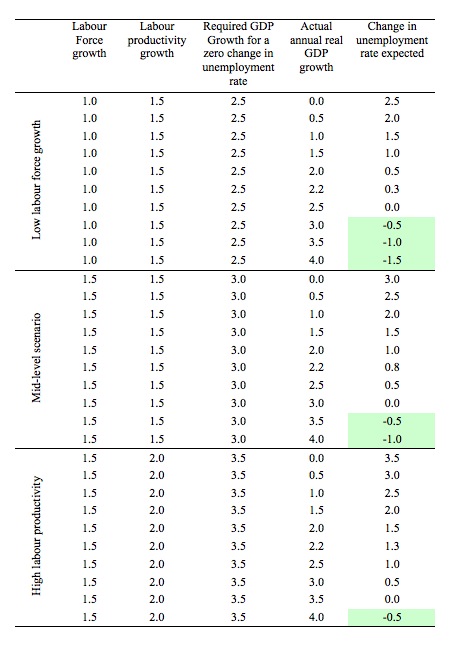

I adopted three scenarios:

1. A low labour force growth assumption (1 per cent per annum) with a mid-level productivity growth assumptions (1.5 per cent per annum).

2. A mid-level labour force growth assumption (1.5 per cent per annum) and productivity growth assumptions (1.5 per cent per annum).

3. A mid-level labour force growth assumption (1.5 per cent per annum) with a high productivity growth assumptions (2 per cent per annum).

The calculations are linear and so you can tinker with the assumptions in any way you see fit.

The following Table shows what the impact on the unemployment rate would be for a range of real GDP growth rates (from zero to 4 per cent). Real GDP growth is currently running around 2.2 per cent. Remember this analysis is approximate.

The green shaded cells coincide with combinations among the aggregates which lead to reductions in the unemployment rate. You can see that under conservative assumptions – the mid-level scenario – real GDP growth has to run at 3.5 per cent per annum or better to really start eating into the unemployment. At 3.5 per cent per annum, under these assumptions it would take until 2018 to get the unemployment rate down to 4.8 per cent (pre-crisis level). At 4 per cent real GDP growth the reduction would be quicker but it would still be 2015 before the “recovery” was complete.

Any factors which would lead to a further slowdown would clearly commit the US to persistently higher unemployment rates for many years. And that is a very costly outcome both in terms of daily lost income and the social damage that ensues.

Conclusion

While America now has decided its President for the next four years I hope that both parties abandon the mindless deficit phobias and get on with creating jobs.

The results tell me that the people are sick of the T Party rhetoric and the Republicans should heed that message and become more co-operative in the Congress. The Blue Democrats should just desist.

And Obama should get some spine.

Gratuitous advice from Australia – free.

Tomorrow – the Australian labor force data for October will be released and so I will write about that.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2012 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Neo – liberal memes just can’t be stopped it seems – even in France , the home of Dirigisme.

Even after the dramatic collapse of the neo liberal poster boy Ireland……….they just keep on coming up with more stuff thats appears to save symbolic money tokens but causes huge externalities that are eventually paid for during collapse phases that somehow was a surprise !!!!

http://ardsl.wordpress.com/2012/10/08/le-car-en-passe-de-concurrencer-le-train/

The liberalization of long distance bus in France will destroy the nodal nature of French towns.

In the 1970s Jacque Chirac (PM) closed down many little used rail lines but preserved a system where the bus network would feed central rail stations just as in the past. – these stations would then have a critical mass of passengers (rail needs large numbers of passengers so as to be viable)

On a holistic level this free market thingy will cause massive resourse misallocation.

This never ending war against rational dirigisme principles is destroying collective wealth / the commons on a scale hard to imagine.

Why are they doing this ?

How much money is enough ?

Whats the point of spending money in a shithole ?

You can only buy shit.

Do Randy and the rest of the bunch have a strategy to effect political change? Are they planning cable TV show appearances? A congressional hearing?

A semantic nitpick worth looking at is whether Bill is “disinterested” or “uninterested” in the big party politics of the USA.

According to englishplus.com

“Disinterested means “impartial” or “not taking sides.” (In other words, not having a personal interest at stake.)

Uninterested means “not interested.” (In other words, not showing any interest.)

Correct: A good referee should be disinterested.

(He does not take sides.)

Incorrect: He was disinterested in Jill’s hobby.

Correct: He was uninterested in Jill’s hobby.

(He shows no interest.)”

My personal take is that Bill is both disinterested and uninterested in formal major party politics of the USA. He realises that both major parties are singing from the same song sheet politically and economically and thus following the same political economy ideology. Bill is right. Neither of these parties can be an agent of genuine change just as neither Liberal nor Labor can be agents of genuine change in Australia. They are all too far down the rabbit hole of neocon unreality.

@Ikonoclast – I was thinking the same thing re the use of ‘disinterested’ and wholely agree with your conclusion. Well said. Cheers!

Bill –

I’m surprised you managed to remain disinterested when Romney’s policy of getting tough on Chinese currency manipulation could’ve been a severe threat to the global economy.

As for the fiscal cliff, I think you might have misunderstood what it is (as I did at first). The tax increases and spending cuts have already been legislated. They now need to be renegotiated to stop the economy plunging back into recession.

Dear Aidan (at 2012/11/08 at 15:16)

My disinterest quip was my attempt at humour – sorry it fell flat.

I fully understand that the US Congress needs to pass new legislation to turn off the “automatic” recession that will head there way if they do not.

While the Republicans should now help get that legislation through I think they will be in denial about what the election results actually mean.

best wishes

bill

I expect the Republicans to be obstructionist.

Aidan – I seriously doubt that Romney had any intention whatsoever of “getting tough on China” … this talking point was probably aimed at securing the support of those who agree with Donald Trump (a reasonably good businessman in the real estate arena, but a wretched economist despite his attending Wharton). Plus there was always the specter of a third-party candidacy by Trump himself, which might have doomed any chance of Romney winning … apart from his own policy preferences with regard to the “debt” and “spending money we don’t have”, etc.

Bill – just curious … perhaps you have heard of Grover Norquist (maybe he even popped up in earlier blogs of yours) and his “pledge” that Republican congress-people must adhere to, which is to never vote for any type of tax increase at the federal level. It seems the coming deal on the “fiscal cliff” will likely include a token rate increase (on which level remains to be seen but I would expect it to be well above the $250K previously stated) in return for some type of fiscal “restraint.” Whether or not such a deal actually passes both Houses, it appears we are indeed headed for recession.