The Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) increased the policy rate by 0.25 points on Tuesday…

Buy a cake on the way to the airport – inflation continues to fall in Australia

The Australian Bureau of Statistics released the Consumer Price Index, Australia data for the June 2012 quarter today and the inflation rate continues to plummet in the face of a slowing economy. The trend over the second half of 2011 was for inflation to ease. But the plunge in the first six months of 2012 that today’s data reveals is suggesting a weakening economy notwithstanding the first-quarter national accounts data which showed above-trend growth. pointing to a very sick economy. The annual inflation rate is now estimated to be 1.2 per cent (down from 1.6 per cent in the 12 months to March 2012) with a downward trend. The Reserve Bank of Australia’s preferred inflation measures – the Weighted Median and Trimmed Mean – are now at or below its inflation targetting range. This suggests that they will soon have to consider inflation to be “too low” and as a result engage in significant monetary policy easing. The inflation trend clearly contradicts the commentators who have been predicting the opposite on the basis of the (modest) rise in the budget deficit over the last few years as the downturn hit Australia. Their standing in the predictions stakes continues to be dented by the data. The evidence is suggesting that the economy is slowing under the weight of the federal government obsession with achieving a budget surplus in the coming fiscal year.

The summary results for the June 2012 quarter are as follows:

- The All Groups CPI rose by 0.5 per cent in the June quarter 2012 compared with a rise of 0.1 per cent in the March quarter 2012.

- The All Groups CPI rose by 1.2 per cent over the 12 months to the June 2012, a fall from the annualised rise of 1.6 per cent over the 12 months to March 2012.

The Sydney Morning Herald article (July 25, 2012) – Weak price gains give RBA room to cut – reported that the inflation results were “less than expected” and provides the Reserve Bank with “more scope to lower rates although its decision also hinges on other factors, including the state of the global economy”.

In that sense, with the World economy in retreat as politicians work to undermine the prosperity of their nations even more than they have already been able to achieve, and inflation below the RBA’s inflation targetting range, one would expect a rate cut.

The Sydney Morning Herals says that annual inflation is at its “lowest reading in 14 years” which is hardly consistent witht he claims that the economy is bursting at the seams and close to full capacity.

The ABC News article (July 25, 2012) – Inflation fall not enough to lift rate cut chances – disputed the notion that the RBA would cut interest rates on the back of the continued plunge in inflation. It quoted a bank economist who said:

Inflation is low and sustainable but it’s not low enough to encourage a rate cut in August. Basically this is right where the RBA wants it …

Which brings into question the RBAs inflation target range – 2 to 3 per cent annualised inflation. As I show below all the measures of inflation that the RBA uses in determining the inflation dynamic are below (or at) the lower bound of the targetting range and falling. They have been falling for nearly 4 years.

So if the current situation is “just were the RBA wants it to be” what is the relevance of that lower bound?

Trends in inflation

The headline inflation rate increased by 0.1 per cent in the March quarter translating into an annualised increase of 1.6 per cent for the year to March 2012 which is down from the December quarter 2011 result of 3.1 per cent.

What does it mean for monetary policy?

The Consumer Price Index (CPI) is designed to reflect a broad basket of goods and services (the “regimen”) which are representative of the cost of living. You can learn more about the CPI regimen HERE.

The ABS say that:

The CPI is a temporal price index for consumption goods and services acquired by Australian resident households. It is an important economic indicator, providing a general measure of price change … The principal purpose of the Australian CPI is to measure inflation faced by consumers to support macroeconomic policy decision making. This is achieved by providing a measure of household consumer inflation by the acquisitions approach.

There are various ways of assessing the general movement in prices depending on the purpose that the measure is being used for. The document I linked to above details some of the approaches. One of these approaches – the “acquisitions approach” – attempts to measure “household consumer inflation” and defines the basket of goods and services as “consisting of all consumer goods and services actually acquired by households during the base period.” The ABS use “market prices for goods and services” (including taxes etc) and make no imputations for “non-monetary transactions” (such as imputed rents). They also exclude “interest rate payments”.

So is a headline rate of CPI increase of 0.1 per cent for the March quarter significant? To examine its lasting significance we have to dig deeper and sort out underlying structural inflation pressures and ephemeral price facts. As the introductory summary shows the price rises are being driven largely by ephemeral factors (and once-off type adjustments – utility prices etc).

The RBA’s formal inflation targeting rule aims to keep annual inflation rate (measured by the consumer price index) between 2 and 3 per cent over the medium term. Their so-called “forward-looking” agenda is not clear – what time period etc – so it is difficult to be precise in relating the ABS data to the RBA thinking.

What we do know is that they do not rely on the “headline” inflation rate. Instead, they use two measures of underlying inflation which attempt to net out the most volatile price movements. How much of today’s estimates are driven by volatility?

To understand the difference between the headline rate and other non-volatile measures of inflation, you might like to read the March 2010 RBA Bulletin which contains an interesting article – Measures of Underlying Inflation. That article explains the different inflation measures the RBA considers and the logic behind them.

The concept of underlying inflation is an attempt to separate the trend (“the persistent component of inflation) from the short-term fluctuations in prices. The main source of short-term “noise” comes from “fluctuations in commodity markets and agricultural conditions, policy changes, or seasonal or infrequent price resetting”.

The RBA uses several different measures of underlying inflation which are generally categorised as “exclusion-based measures” and “trimmed-mean measures”.

So, you can exclude “a particular set of volatile items – namely fruit, vegetables and automotive fuel” to get a better picture of the “persistent inflation pressures in the economy”. The main weaknesses with this method is that there can be “large temporary movements in components of the CPI that are not excluded” and volatile components can still be trending up (as in energy prices) or down.

The alternative trimmed-mean measures are popular among central bankers. The authors say:

The trimmed-mean rate of inflation is defined as the average rate of inflation after “trimming” away a certain percentage of the distribution of price changes at both ends of that distribution. These measures are calculated by ordering the seasonally adjusted price changes for all CPI components in any period from lowest to highest, trimming away those that lie at the two outer edges of the distribution of price changes for that period, and then calculating an average inflation rate from the remaining set of price changes.

So you get some measure of central tendency not by exclusion but by giving lower weighting to volatile elements. Two trimmed measures are used by the RBA: (a) “the 15 per cent trimmed mean (which trims away the 15 per cent of items with both the smallest and largest price changes)”; and (b) “the weighted median (which is the price change at the 50th percentile by weight of the distribution of price changes)”.

While the literature suggests that trimmed-mean estimates have “a higher signal-to-noise ratio than the CPI or some exclusion-based measures” they also “can be affected by the presence of expenditure items with very large weights in the CPI basket”.

The authors say that in the RBA’s forecasting models used “to explain inflation use some measure of underlying inflation (often 15 per cent trimmed-mean inflation) as the dependent variable”.

The special measures that the RBA uses as part of its deliberations each month about interest rate rises – the trimmed mean and the weighted median – also showed moderating price pressures.

So what has been happening with these different measures?

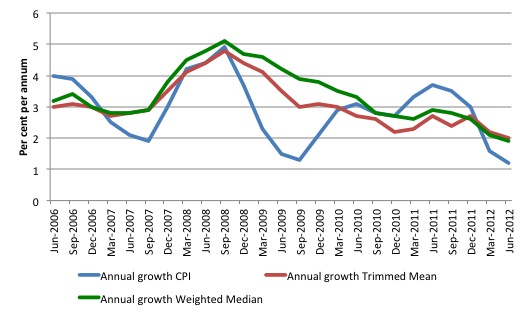

The following graph shows the three main inflation series published by the ABS – the annual percentage change in the all items CPI (blue line); the annual changes in the weighted median (green line) and the trimmed mean (red line). The RBAs inflation targetting band is 2 to 3 per cent. The CPI measure of inflation (at 1.2 per cent down from 1.6 per cent in the March quarter) is now below the lower limit and continues to fall while the RBAs preferred measures – the Trimmed Mean and the Weighted Median – are now at or below the RBAs lower target band of 2 per cent.

In seasonally adjusted terms, the annual growth in the weighted median fell to 1.9 per cent in the June quarter (from 2.2 per cent in the March quarter). The trimmed mean fell to 1.9 per cent in the June quarter (from 2.1 per cent in the March quarter).

The trend in all measures is downwards and has been consistently so for the last 15 quarters – that is, nearly 4 years.

First, it is clear that the RBA-preferred measures are now at or below the the bottom end of their inflation-targeting band and falling. Even using their own logic the interest rate should be cut to bring inflation back into its targetting range.

Second, the underlying price pressures (say from wages) are declining as the economy slows. There is no inflation threat in Australia at present. The problems are all real – that is declining growth and rising unemployment. They should be the policy emphasis.

The Treasurer’s obsession with getting the federal budget back into surplus is now well and truly out of kilter with what is happening in the broader economy. One of the big risks that commentators claim was behind the alleged need to withdraw the fiscal stimulus – inflation – is declining. The other risk – higher interest rates (notwithstanding that the RBA sets the rates anyway) – are now looking like they will have to fall to provide some support for aggregate spending, which is in retreat.

The problem, of-course, is that monetary policy has a very indirect and uncertain impact on aggregate demand but remains the counter-stabilisation policy of choice for policy makers obsessed with budget surpluses.

The indications are that the budget deficit should be higher not lower – given that 12.5 per cent of available workers in Australia are either unemployed or underemployed. That is not to mention the fact that teenage employment has contracted overall since February 2008, when the crisis started to impact negatively on the Australian economy.

What is driving inflation in Australia?

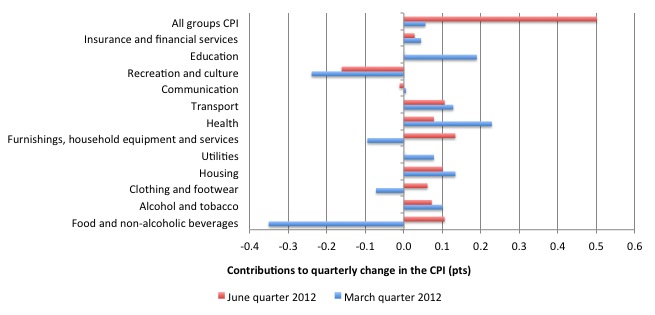

The following bar chart compares the contributions to the quarterly change in the CPI for the June 2011 quarter (red bars) to the March 2012 quarter (blue bars).

The ABS reports that for the March 2012 quarter, the largest price rises were for medical and hospital services (+2.8 per cent), rents (+1.1 per cent), vegetables (+5.2 per cent) and furniture (+4.5 per cent).

The ABS reports that for the March 2012 quarter, the larger price falls were for domestic holiday travel and accommodation (-4.0 per cent), audio, visual and computing equipment (-3.8 per cent) and cakes and biscuits (-2.8 per cent).

That is, buy some cakes on the way to the airport and don’t forget your MP3 player.

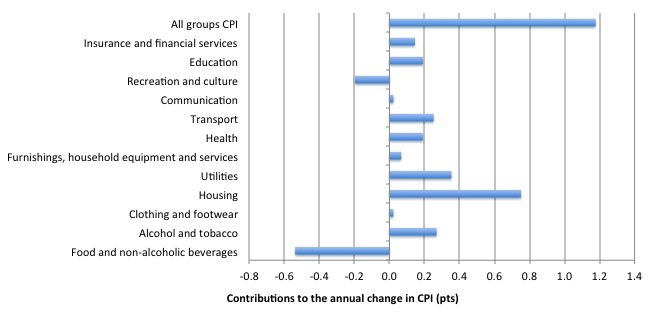

The next bar chart provides shows the contributions in points to the annual inflation rate by the various components.

In 2011, food prices were a significant driver of inflation as a result of the floods and cyclone but that impact has clearly not been a factor over the last year, although some vegetables are becoming more expensive as winter hits.

International travel is being aided by the high value of the dollar as is audio, visual and computing equipment (Apple products excepted which seem to be getting more expensive).

The overwhelming conclusion is that there is no evidence that there is any likelihood of an inflation outbreak in Australia at present.

Which should give the commentators who a few years ago were predicting rising interest rates and accelerating inflation as a result of the two federal stimulus measures which pushed the budget deficit up.

ABC Video Segment – Inflation Targetting

Last Friday, I did an interview for ABC TV in its Melbourne Southbank studios on inflation targetting and budget deficits. The following 4:08 minute video shows a small snippet from that interview which was part of a segment on Inflation Targetting broadcast last night (July 24, 2012) on the national ABC Lateline Business program.

I gave a long interview (about 20 minutes or so), which apparently will be used in other segments in the coming weeks.

The journalist did ask me about the comment made by the bank economist that since inflation targetting the Australian unemployment rate has been “significantly lower” but chose not to include my answer.

So here is more or less what I said in reply:

1. Even the OECD has recently acknowledged in their Employment Outlook 2012 – that despite our official unemployment rate being below those currently found in other advanced nations that:

… Nevertheless, underemployment continues to be a significant problem … [and] … More than 12% of the labour force are now either unemployed or working part-time and would like to work longer hours … in the fourth quarter of 2011, Australia’s rate of underemployment is much higher than the OECD average of 5.0%, so that total labour underutilisation in Australia is close to the OECD average, despite much lower unemployment.

Since inflation targetting began in 1994 our broad labour

2. The 20 years prior to the onset of inflation targetting were characterised by the two major recession and so a statement that unemployment in a period of growth is significantly lower than two decades where unemployment went through the roof hardly says much.

A more relevant comparison is to consider what the unemployment rate in the period since inflation targetting has been relative to other stable growth periods. That comparison is not very attractive.

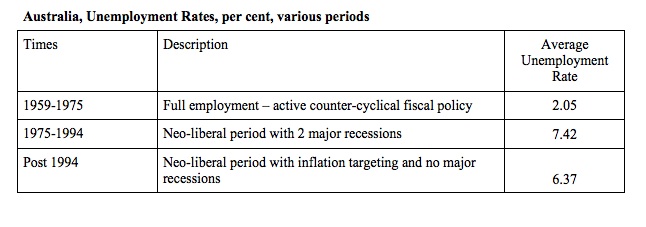

To support that claim the following table compares the official unemployment rate for Australia for three discrete periods since September 1959 (when reliable data began). The first period broadly ran up until the mid-1970s and is fairly characterised as a period of true full employment which was made possible by an explicit commitment of the federal government to use counter-cyclical fiscal policy to maintain enough jobs in the economy at all times.

The second period ran from the mid-1970s until early 1994 and is characterised as the growing neo-liberal influence on policy, with major privatisations and deregulation and the obsessive pursuit of federal budget surpluses. Two major recessions – 1982 and 1991 – occurred during this period.

The third period from early 1994 until the present is the period of formal inflation targetting and a period of constant economic growth although driven by ever increasing levels of household debt. The neo-liberal deregulation gathered pace during this period.

It doesn’t take much imagination to understand that the latter period has not delivered “significantly” lower unemployment rates at all when compared to the non-targetting neo-liberal period prior to it which was burdened by two major recessions.

The relevant comparison is the stark difference between the period when there was a federal government commitment of full employment and the subsequent periods when they abandoned that commitment and pursued neo-liberal options.

And I haven’t even factored in the rise in underemployment (from virtually nothing to over 7.5 per cent now) which has accompanied the inflation targetting period.

The bank economist in the video might better present history in the future (eh Chris?).

3. I also noted that in terms of the aggregates that the mainstream claim are improved under inflation targetting regimes (price stability, lower levels of inflation and variability, and higher real GDP growth) the extant research shows that there is no difference between the performance of nations that adopted inflation targetting and those that did not.

Further real GDP growth has been lower on average during the inflation targetting period than previously.

Inflation targetting did not bring low inflation to Australia – the 1991 recession (our worst since the 1930s) was responsible for that.

4. Most significantly, I said that the ideology that brought us inflation targetting was part of an overall package that also brought us financial and labour market deregulation; a growing gap between real wages growth and productivity growth, which has seen a major redistribution of national income towards profits; growth dependent on ever increasing levels of private (particularly household) debt; and as a result the worst economic crisis since the 1930s, with no end yet in sight.

So the fantasy that inflation targetting has provided the world with stable economies is a total farce. It is part of a neo-liberal ideology that has wrought havoc on the world.

Conclusion

After falling steadily over the last half of 2011 and into 2012, the annual Australian inflation rate dropped significantly in the June quarter 2011 as the transitory push factors such as natural disasters and external factors (petrol prices) dissipated and the full impact of the declining real growth rate in the economy started to impact.

Related data shows there are no significant generalised wage pressures in the economy at present.

The data continues to suggest that the national economy is slowing notwithstanding the strength in the mining regions.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2012 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Our politicians all seem to fancy themselves as accountants and not asset managers. You can always spend less, just don’t expect a positive social outcome if you have mis-managed the human resource aspect. Corporations have never discovered the secret to the self-managing project. It would be surprising to have a self-managing economy simply by tweaking inflation perception.

The year 2000 appeared idyllic in the US, the numbers looked good, but we were sitting on a calm ocean with an eight knot current drawing us to shipwreck. For ten years we had been shipping jobs, white and blue collar, to Asia. We sent factories abroad as well as the machines that made machines of production, while firing the men that made them. The value capture class was loading us up with credit card debt, mortgage debt, home equity debt, student loan debt, city debt, state debt, and ultimately national bailout debt. We started several discretionary wars, experienced a housing bubble, and then the shipwreck. Up until then, the accountants told us to wear sunglasses, the future looked so bright.