The other day I was asked whether I was happy that the US President was…

The lessons of history – subtitled – are the Dutch printing guilders?

There was a Wall Street Journal article (March 14, 2012) – Default and the Nature of Government – which demonstrates how a recall to history can be misused if key additional (contextual) information is left out of the discussion. The article in fact tells us nothing meaningful about the likelihood of sovereign debt default. The sub-title relates to the latest news from the Netherlands which suggests that the strident rhetoric of their leadership about the failure of the “southern” states to meet their obligations to the Eurozone might now be coming back to haunt them. If they are not, then they should. If the Dutch are to be consistent then massive and destructive penalties should now be imposed on them by Brussels. They won’t be – but that just tells you how dysfunctional the Eurozone is!

Reflect back on this Reuters report (November 15, 2011) – Dutch push for “budget tsar” in midst of crisis – which is representative of many press releases, speeches, news reports coming out of Den Hague over the last several months..

In it we read that:

When it comes to thinking ahead in the midst of a crisis, look to the Dutch.

With upheaval in Italy and Greece threatening the euro zone’s very existence, the critical issue for the Netherlands is creating a ‘budget tsar’ with powers potentially to expel unruly members and prevent future debt crises.

At emergency meetings from Poland to Luxembourg, Dutch Finance Minister Jan Kees de Jager has rarely missed an opportunity to make his point — that only intense oversight of others’ budgets can prevent another meltdown.

De Jager has been one of the most strident Northern Europeans pushing for austerity and harsh treatment of the southerners. That’s him below looking well fed and far from unemployed.

The Reuters article quotes him as saying:

You can’t solve a debt crisis with more money, that is the lesson from this crisis … You need more tools, you need budget oversight.

When a crisis is principally caused by a lack of spending then more “money” is exactly what is required.

This character has been one of the leading voices advocating for “creating an EU budget authority run by a powerful commissioner who could intervene in government budgets if countries ignored debt targets, gradually taking over their finances and potentially expelling them from the euro zone”.

De Jager has advocated:

… aggressive, automatic sanctions for those that break debt and deficit rules and a budget tsar with the power to withdraw EU subsidies and force countries to raise taxes.

The Dutch Europe Minister is also part of the Dutch austerity chorus and was quoted as saying:

Some people might say our focus is too much long term, but the market looks at future risks and prices it in … It is imperative to get a grip on enforcement of budget discipline rules. We should never have a repeat of any country, big or small, flouting the rules.

The Dutch are unhappy with the current SGP rules (“penalties for those that run deficits of more than 3 percent and have debts greater than 60 percent of GDP”).

They are fierce advocates of the fiscal compact (balanced budgets) and want harsh penalties for breaches.

So I suppose Meneer De Jager will be getting the cheque book out as I type and start signing the cheque to send to Brussels for being serial offenders with respect to the current fiscal rules. He will presumably also be ringing the Dutch mint and getting them to start the guilder printing presses again given that the Netherlands, using their own logic will have to exit the Eurozone.

The Dutch economic advisory bureau – the Central Planning Bureau – has just published its updated – Main Economic Indicators 2011-2015 in the light of its slowing economy.

The revised forecasts are not pretty.

The CPB say that the Dutch economy is now likely to worsen on their most recent forecast (December 2011) “mainly due to the unfavourable economic developments … a decrease of consumer spending levels, most likely due to lower consumer confidence levels, deteriorated (pension fund) wealth and decreasing housing prices”.

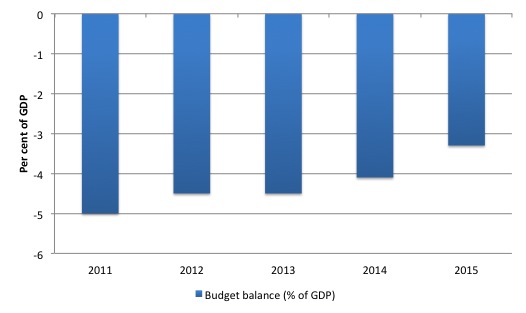

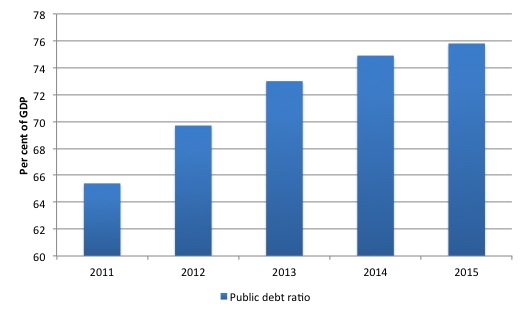

The failing economy will impact on the forecast budget deficit as a result of operation of the automatic stabilisers. The CPB forecasts for the budget deficit and public debt (as a percentage of GDP) for the period 2012-2015 are shown in the following graphs.

The first graph shows the budget deficit forecasts. Now a little bit of interactive time. Locate -3 on the vertical axis of the first graph and trace it across the bars.

Research task 1: See if you can find any bar over the forecast period that is lower than the traced out line in the graph.

The second graph shows the public debt ratio forecasts. Now locate +60 on the vertical axis of the second graph and trace it across the bars.

Research task 2: See if you can find any bar over the forecast period that is lower than your traced out line in the graph.

The CPB says that:

The forecasted budget deficit in 2013 is 4.5 percent. This means that the EMU-ceiling of 3 percent budget deficit will be passed by 9 billion euros. Should public policies remain unchanged the deficit will be 4.1 percent in 2014 and 3.3 percent in 2015. Unemployment increases to 6 percent in 2013, which amounts to 545.000 persons.

So not only will the Dutch economy violate the SGP rules as they presently are, but they have no hope within the next three years at least of getting close to the fiscal compact rule that they have been vehemently promoting.

And in the meantime, unemployment will rise.

Pity the Dutch population, if the Finance Minister starts to practice what he so fervently preaches.

This, of-course, is part of the spreading crisis which is seeing recession hit the European strongholds of Germany and the Netherlands. It demonstrates the failure of the leaders to both understand what the problem is and to implement a satisfactory solution. The second follows the first.

And while on the Eurozone, we can now consider that Wall Street Journal article briefly. The article was written by one Alex Pollock who is a “resident fellow at the American Enterprise Institute”, the Washington-based neo-conservative lobby group, which masquerades as a research organisation.

The American Enterprise Institute’s vast list of conservative advisers include Mr Efficient Markets Theory (Chicago’s Eugene Fama who denies that the current crisis represents market failure) and Harvard’s Martin Feldstein who starred (ignominiously) in the movie Inside Job.

Please read my blogs – Evidence – the antidote to dogma – for more discussion on Fama and Martin Feldstein should be ignored – for more discussion on Feldstein. Their association with the AEI is significant.

I am always interested in finding out who funds these institutions. Unfortunately, while the 2011 Annual Report discloses they received about $US32 million last year they fail to disclose the sources, which always raises suspicians in my mind.

The US organisation – Media Matters has done some great work tracking down who provides funds to the AEI (and other conservative organisations), although their work is not exhaustive,

The AEI published the WSJ article on their own site under the heading Financial History Lessons, although my assessment of the educational content is near to zero given that its logic would lead to erroneous conclusions in the current period.

An historical lesson is only pertinent if it allows us to understand the past better and apply that understanding to the present. This article achieves neither aim.

Mr Pollock’s opening gambit sets the scene:

Twenty-first century economists, financial actors and regulators blithely talked of the “risk-free debt” of governments, and European bank regulators set a zero-capital requirement on the debt of their governments. The manifold proof of their error is that banks and other investors are now taking huge credit losses on their Greek government bonds.

Perceptive readers, who are well-versed in Modern Monetary Theory (MMT), will immediately see the flaw in this argument. For those unsure let me explain.

No economist who understands the intrinsic characteristics of different monetary systems would “blithely” talk about risk-free debt in relation to the public debt issued by a Eurozone member state.

They would also not conflate the EMU with the monetary systems operating in, say the US, Japan, the UK, Australia, etc.

One of the contributions of MMT, I believe, is to differentiate the nature of monetary systems according to the sovereignty held by the national government.

A member state of the EMU effectively uses a foreign currency. It doesn’t issue the currency it uses, and, as a result, must fund its spending from its tax revenue and then by borrowing where deficits occur.

This recognition, immediately leads to the conclusion that the debt that such a government is issuing is not risk-free. All EMU member-states face insolvency risk.

Should such a state not be able to raise enough revenue to cover their spending then all their contractual obligations are at risk.

Given the depth of the negative aggregate demand shock that the EMU economy received in 2008 it was little wonder that some of the more exposed nations would encounter fiscal challenges as their tax revenue base shrank. The solution at that time was obvious – the ECB should have immediately funded expansionary programs (that is, fill the fiscal void created by the flawed design of the Eurozone) and promoted growth.

The imposition of fiscal austerity, as a result of some narrow-minded interpretation of the restrictive fiscal rules that EMU nations operate within, was the last thing that should have been contemplated, let alone implemented.

So, given the ECB intransigence and the unethical behaviour of the Troika, it is little wonder that public debt defaults are now being seen in Europe.

However. these defaults provide no information about the credit risk associated with public debt in truly sovereign countries, which issue their own currencies under monopoly conditions.

For those countries, there is no credit risk inherent in the financial instrument issued by their national governments.

Such governments can always meet their liabilities, as long as they are the denominated in the currency that they issue. Mr Pollock appears not to understand that basic point.

So while he uses authoritative terms like “the manifold proof of their error” we can conclude that he doesn’t know what he is talking about and this is just another neo-conservative beat up designed to advance the ideological agenda of his masters.

In relation to those “huge credit losses” that investors in Greek government bonds are now being forced to take let me say the following.

There was absolutely no justification for the Troika to force the losses onto persons and institutions who placed their savings in Greek government bonds in good faith. It is almost unbelievable that the Eurozone leaders can keep a straight face when announcing the necessity for a PSI.

What message does that send to savers about the viability of buying Euro-denominated financial assets?

What message does that send the Irish, who are struggling under the burdens of austerity? And the Spanish? And the Portuguese? And then, of-course, the Italians?

Stay tuned for more demands for PSI from these nations. If one nation doesn’t have to pay its debts, why should others?

The Eurozone has an infinite minus one euro capacity, via the ECB, which issues the currency that the member states use, to guarantee all public debt.

I found it extraordinary that the Euro leaders would behave in this immoral and economically-stupid manner.

The next cab off the rank will probably be the upcoming promissory notes in Ireland that have to be negotiated.

What’s good for the goose is good for the gander! The Euro leaders decision has opened a Pandora’s box, which will haunt them for years to come.

Mr Pollock continues his discussion of the Eurozone defaults with the following:

The only question is why anybody would be surprised by this. The governments of country after country defaulted on their debt in the 1980s, a mere generation ago. In a longer view, Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff count 250 defaults on government debt from 1800 to the early 2000s. As Max Winkler wrote in his instructive 1933 book, “Foreign Bonds: An Autopsy”: “The history of government loans is really a history of government defaults.”

Winkler chronicled many examples of government defaults and repudiations of debts up to 1933, including those of Austria, Bolivia, Brazil, Bulgaria, Canada, Chile, Ecuador, Costa Rica, Germany, Greece, Guatemala, Latvia, Mexico, Peru, Romania, Russia, Turkey and Yugoslavia-as well as those of a dozen U.S. states.

Like a lot of commentators at present, he seizes on the work by Carmen M. Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff (the main recent title being This Time is Different) and uses it as an authority to justify the historical veracity of his argument.

Since publication, this book has become a bible for the deficit terrorists. I wonder how many have actually read it in detail and understood the applicability of its contents.

Here is draft version of This Time is Different that you can read for free.

Of critical importance, quite apart from the other issues that one might have with Reinhart and Rogoff’s analysis (and I have many), one has to appreciate what they are talking about. Most of the commentators do not spell out the definitions of a sovereign default used in the book. In this way they deliberately (or through ignorance – one or the other) blur the terminology and start claiming or leaving the reader to assume that the analysis applies to all governments everywhere.

It does not. On Page 2 of the draft, Reinhart and Rogoff say:

We begin by discussing sovereign default on external debt (i.e., a government default on its own external debt or private sector debts that were publicly guaranteed.)

How clear is that? They are talking about problems that national governments face when they borrow in a foreign currency. So when so-called experts like Mr Pollock claim that their analysis applies generally you realise immediately that they are in deception mode or just don’t understand the scope of the study they are drawing on for authority,

The US government, for example, has no foreign currency-denominated debt. Remember it has domestic debt owned by foreigners – but that is not remotely like debt that is issued in a foreign currency. Reinhart and Rogoff are only talking about debt that is issued in a foreign jurisdiction typically in that foreign nation’s currency.

Japan has no foreign currency-denominated debt. Many other advanced nations have no foreign currency-denominated debt.

It turns out that many developing nations do have such debt courtesy of the multilateral institutions like the IMF and the World Bank who have made it their job to load poor nations up with debt that is always poised to explode on them. Then they lend them some more.

But it is very clear that there is never a solvency issue on domestic debt whether it is held by foreigners or domestic investors.

Reinhart and Rogoff also pull out examples of sovereign defaults way back in history without any recognition that what happens in a modern monetary system with flexible exchange rates is not commensurate to previous monetary arrangements (gold standards, fixed exchange rates etc). Argentina in 2001 is also not a good example because they surrendered their currency sovereignty courtesy of the US exchange rate peg (currency board).

Further, Reinhart and Rogoff (on page 14 of the draft) qualify their analysis:

Table 1 flags which countries in our sample may be considered default virgins, at least in the narrow sense that they have never failed to meet their debt repayment or rescheduled. One conspicuous grouping of countries includes the high-income Anglophone nations, the United States, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. (The mother country, England, defaulted in earlier eras as we shall see.) Also included are all of the Scandinavian countries, Norway, Sweden, Finland and Denmark. Also in Europe, there is Belgium. In Asia, there is Hong Kong, Malaysia, Singapore, Taiwan, Thailand and Korea. Admittedly, the latter two countries, especially, managed to avoid default only through massive International Monetary Fund loan packages during the last 1990s debt crisis and otherwise suffered much of the same trauma as a typical defaulting country.

Britain has defaulted only once in its history – during the 1930s – while it was on a gold standard. The Bank of England overseeing an economy ravaged by the Great Depression defaulted on gold payments in September, 1931. The circumstances of that default are not remotely relevant today. There is no gold standard, the sterling floats. Britain has never defaulted when its monetary system was based on a non-convertible currency.

A large number of defaults are associated with wars or insurrections where new regimes refuse to honour the debts of the previous rulers. These are hardly financial motives. Japan defaulted during WW2 by refusing to repay debts to its enemies – a wise move one would have thought and hardly counts as a financial default.

But if you consider the “virgin” list – how much of the World’s GDP does this group of nations represent? Answer: a huge proportion, especially if you include Japan and a host of other European nations that have not defaulted in modern times.

Further, how many nations with non-convertible currencies and flexible exchange rates have ever defaulted? Answer: hardly any and the defaults were either political or because they were given poor advice (for example Russia in 1998).

Reinhart and Rogoff don’t make this distinction – in fact a search of the draft text reveals no “hits” at all for the search string “fixed exchange rates” or “flexible exchange rates” or “convertible” or “non-convertible”, yet from a MMT perspective these are crucial differences in understanding the operations of and the constraints on the monetary system.

Further, if you consider the Latin American crises in the 1980s, as a modern example, you cannot help implicate the IMF and fixed exchange rates in that crisis. The IMF pushed Mexico and other nations to hold parities against the US dollar yet permit creditors to exit the country. For Mexican creditors this meant that interest returns skyrocketed (the interest rate rises were to protect the currency) and the poor Mexicans wore the damage.

It was clear during this crisis that the IMF and the US Federal Reserve were more interested in saving the first-world banks who were exposed than caring about the local citizens who were scorched by harsh austerity programs.

Please read my blog – Watch out for spam! – for more discussion on this point.

Conclusion

Organisations such as the American enterprise Institute seem hell-bent on pressuring the American government to follow the fiscal austerity path to recession.

The arguments are not based upon an understanding of of economic theory or the way in which the economy operates under conditions of monetary sovereignty.

Rather, they reflect an ideology that is both destructive and make believe. Sadly, the most disadvantaged citizens suffer the costs of the policy folly that follows when governments listen to this nonsense.

Saturday Quiz

The Saturday Quiz, now into its 156th edition will be back tomorrow sometime. I keep my fingers crossed that the statistics will reveal that no-one has accessed the page, as a result of total boredom with the Quiz, which will lead me to retire it gracefully.

But in the meantime, look out for it tomorrow.

That is enough for today!

Bill,

We love the Saturday quiz. Each week it reminds us not to get too big for our boots and that we have much to learn.

A weekly dose of humility is no bad thing in a Facebook world. It keeps us grounded in reality.

I hope that you will be able to keep it going.

Dear Bill

First, let me be a nitpicker by saying that it is Centraal Planbureau, not Centraal Planning Bureau.

Second, one reason why the Dutch government is so vehement about fiscal sternness for other eurozone members is that the current Dutch government is a minority government dependent on the support of the PVV, the anti-immigration, Islamophobic party of Geert Wilders. Geert Wilders has steadfastly opposed any aid to Greece, and recently he asked a British research institute to investigate whether the introduction of the euro was beneficial to the Dutch economy. Conclusion from the institute: the Dutch were on balance losers from the euro and would benefit from the reintroduction of the guilder.

Thirdly, there is no insolvency risk when lending to a government that enjoys full monetary sovereignty, but there is an inflation risk for domestic creditors and an exchange rate risk for foreign creditors. You will get your money back, but there is no iron-clad guarantee that the money that you get back will have the same purchasing power as the money that you lent out.

Have a good weekend. James

@James Schipper

Most of the buyers of sovereign debt (especially in countries like USA) are primary dealers, banks and other financial institutions with access to central bank or interbank lending. Investors like pension funds are a minority and actually have to compete with primary dealers for a piece in bond auctions (in the US, primary dealers bid-to-cover ratio is usually more than 2:1).

Furthermore, sovereign debt has a zero risk weight. As a result, buyers do not face any capital cost (compared to loans to the private sector) and their funding cost is set by the central banks rates (repo rates for primary dealers, interbank rates for banks/hedge funds). Their Return On Equity is higher, the more debt they buy. If an inflation episode is created by increased government deficits (assuming an economy at full employment), banks/primary dealers/hedge funds have every reason to buy as much of the issued debt as possible to hedge their RoE against inflation. Obviously that is not the same for pension funds and foreign central banks (and other holders of sovereign debt investing saved funds) but their actions will be more complicated and depend on exchange rate movements, current account deficits, portfolio management and exposure to the country’s economy (pension funds will still invest in sovereign debt since that is the only risk-free asset in town).

I love the weekly quizzes, Bill. For two reasons:

1. For me, they arrive on Fridays. And every week I’m all like WTF??? Followed by…oh never mind…tricky Australians. Happens every time.

2. For T/F questions, I spend quite a bit of time thinking through the question and when I am confident of the answer, I choose the opposite. 100% accuracy. This makes my feel like the smartest person in the world.

Keep ’em coming! I’ll eventually start getting some wrong.

“Thirdly, there is no insolvency risk when lending to a government that enjoys full monetary sovereignty, but there is an inflation risk for domestic creditors and an exchange rate risk for foreign creditors. You will get your money back, but there is no iron-clad guarantee that the money that you get back will have the same purchasing power as the money that you lent out”

The relevant points are that sovereign governments do not in fact need to issue debt (unless you classify currency and exchange settlement accounts as government debt). It is the private sector that needs that debt to be issued, as the private sector needs a set of nominally risk free securities in which it can invest, which can act to provide a (nominally) risk free benchmark set of interest rates as a basis for the yield curve and the general structure of interest rates.

A stable and robust financial system, as Hyman Minsky used to point out, is one with a high level of risk free government debt in private sector balance sheets.