I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

A Way Forward

Sometimes, not often, I read some economic analysis that is sound. In the constant barrage of mainstream economics telling us that budget deficits are causing the crisis to linger; that interest rates are about to rise sharply because there is too much public debt; that inflation is about to go hyper because bank reserves have risen; that taxes will soon sky-rocket to pay back the debt; and all the rest of the lies that students are forced by lecturers around the world to rote learn, to find a well-reasoned piece of analysis is very refreshing. My attack dog propensities subside and I am able to think about what is being written – seeing where I agree and disagree and even learn some things. Such was my experience this morning when I read a new Report from the US-based The Way Forward Moving From the Post-Bubble, Post-Bust Economy to Renewed Growth and Competitiveness. It will not be a case of common sense prevailing because the forces against this type of clear thinking are many and powerful. But it is evidence that views that are not incompatible with Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) are being developed and thrown into the public debate. In this case, the authors also have some public profile. The ideas in this Report would provide a Way Forward.

The Way Forward report was published by the New America Foundation which says it “is a nonprofit, nonpartisan public policy institute that invests in new thinkers and new ideas to address the next generation of challenges facing the United States”. While it did receive some funding from the Peter G. Peterson foundation, that influence appears to be diluted somewhat. It is clearly not a PGPF front, unlike many of the other “think-tanks” that are offering public policy proposals at present and seem to dominate the media coverage of the crisis.

There is a brief (and positive) discussion of the Report in an New York Times Op Ed (October 10, 2011) – This Time, It Really Is Different – which noted that the analysis “ought at least give our politicians pause” and that “(i)ts proposed solutions are far more ambitious than anything being talked about in Washington”. That alone, tells me how far out of kilter the public debate has become because the “proposed solutions” are not radical and would have been mainstream prior to the hijacking of public sensibilities by the neo-liberal onslaught.

I won’t attempt here to provide a blow-by-blow account of my reading of this 35-page Report – I am typing this in an airport lounge and will run out of time today before I could do that. But there are several highlights that should be headlines in the daily press that are worth lingering on.

The NAF Report informs us how bad things are in the US (and elsewhere) – the indicators are horrific in fact – insipid employment growth, entrenched unemployment and rising underemployment, historically weak business investment, a “massive private sector debt overhang” weighing down private spending and wiping out private wealth (as the property market collapse) and the rest of it.

The economic “peril” is global and the current growth drivers – like “China and other large emerging economies” are slowing. The advanced world is facing a protracted Japan-like period of economic stagnation – or as they say:

Protracted stagnation on this order of magnitude would undermine the living standards of an entire generation of Americans and Europeans, and would of course jeopardize America’s position in the world.

All of which from an MMT perspective is unnecessary and is capable of resolution if only policy makers abandoned their neo-liberal leanings and sought support from the broader population rather than a narrow group of financial elites who are milking this crisis for all it is worth (to them).

The NAF Report recognises the “political dysfunction and attendant paralysis in both the United States and Europe”. That should be the focus of grass roots movements to produce a new generation of politicians to replace the current failed representatives and career political class. It is clear the current crop have been captured by the elites and are at the centre of the problem rather than providing leadership to implement a coherent solution.

The news just came up on the TV screen in the lounge that indicated that the Senate Republicans vote to kill jobs plan in the US. The plan was pathetic but better than nothing. The Republicans continue to demonstrate that they don’t understand basic economics and certainly don’t care about the prospects of the American people.

The NAF authors say:

For despite the standoff over raising the U.S. debt ceiling this past August, the principal problem in the United States has not been government inaction. It has been inadequate action, proceeding on inadequate understanding of what ails us.

That is clear. The stimulus packages were inadequate because they were not large enough in terms of demand injection and were not targetted enough in terms of jobs. They were also withdrawn too soon. Further, the irrational belief that monetary policy (QE etc) would provide the heavy lifting in terms of demand stimulus was always going to fail. This reliance reflects the mainstream promotion of monetary policy as the principle tool for counter-stabilisation while eschewing active use of fiscal policy.

The crisis caused the pragmatic response by politicians – given they were staring at a reprise of the Great Depression or worse – and so the mainstream economics objection to fiscal policy intervention was temporarily abandoned in favour of the politicians being seen to be doing something. The stimulus packages that were introduced did head-off the worst prospects that were being faced in 2008.

The NAF Report acknowledges that:

Since the onset of recession in December 2007, the federal government, including the Federal Reserve, has undertaken a broad array of both conventional and unconventional policy measures … These actions have undeniably helped stabilize the economy-temporarily.

Temporarily is the point. The mainstream economists supported by the billions available from the free market elites to finance think-tanks, buy Op Ed space, etc staged a massive fightback and essentially have pressured governments in to introducing very conservative stimulus packages and then withdrawing the fiscal support to early. But it has gone further than that – we now have fiscal austerity as the main game despite it clearly undermining growth where it has been implemented.

I should note that the free market elites actually don’t want a free market at all but a market that makes things free for them.

While acknowledging that the fiscal and monetary interventions provided temporary help, the NAF Report says that the “continuing high unemployment and the weak and now worsening economic outlook” is evidence that “they have not produced a sustainable recovery”.

They consider that the current policy proposals (American Jobs Act etc) will not help much. They also think that monetary policy has “reached the limits of … effectiveness”.

There are several reasons outlined for the lack of policy effectiveness.

In categorising the downturn as a “balance-sheet Lesser Depression or Great Recession of nearly unprecedented magnitude” the authors note that the “massive debt overhang” (and negative equity in the housing sector) is proving to be highly deflationary and protracted.

Please read my blog – Balance sheet recessions and democracy – for more discussion on this point.

When a balance-sheet recession occurs, the only way out is for the private sector to increase saving and reduce its debt and for that process to be supported by fiscal policy intervention for as long as it takes. The private balance sheets have to be repaired and it takes a lengthy period. So all the haste by the conservatives (including the IMF and other international organisations) to bring credible fiscal consolidation before the world economy had achieved even modest debt reduction was premature and damaging. It reflected a major failure to understand the nature of the crisis – its causes etc.

The NAF Report indicates that other developments have made the crisis worse that it otherwise would have been. They note the rise of the “new export oriented economies” – Japan, the Asian tigers and now China – has “decisively shifted the balance of global supply and demand”. These low wage countries have still not developed domestic markets fully and so the shift in economic power has led to “excess supplies of labor, capital, and productive capacity relative to global demand” which “profoundly dims the prospects for business investment and greater net exports in the developed world”.

As the Report notes these are the “only other two drivers of recovery when debt-deflation slackens domestic consumer demand”.

Which is a strange thing to say. The correct statement is that they are the only remaining non-government sources of growth. Moreover, the Report could have noted that the shift in world economic activity to the export-orientated low wage economies did not have to lead to a surplus supply capacity relative to demand.

What was required as this process of regional and industrial compositional change was occuring was for national governments in the advanced nations to use their fiscal capacity to develop new uses of labour in the domestic economy. A shift to more personal care and environmental care services was necessary. Nations like Norway have succeeded in this public-sector led structural change whereas the WASP nations have failed. The reason is that the English-speaking world has been more vehemently hooked on neo-liberal concerns for debasing the role of the government.

When government should have been stepping up to the plate to ensure that the lost production would not lead to excess supplies in their own economies they actually – at the behest of the neo-liberals – actively worked to make the problem more severe.

The NAF Report notes a further development that has made the crisis more severe. They acknowledge that:

Because many workers were no longer sharing the fruits of the economy’s impressive productivity gains, capital was able to claim a much larger share of the returns, further widening wealth and income inequality which by 2008 had reached levels not seen since the fateful year of 1928.

This is one of my regular themes. Please read my blog – The origins of the economic crisis – for more discussion on this point.

The combination of shrinking wage-led purchasing power and the rise of the financial sector (using the real income redistributed away from workers) which pushed credit onto the depleted workers was a lethal recipe. Consumption growth (and housing prices) were maintained while the credit expansion was on-going but it had to crash once the margin of risk became too great. In their greed to saturate the private sector with credit, the financial sector lost track of the risk exposure.

The aftermath is a very subdued consumption outlook while households pay back the debts.

I am in agreement with most of this assessment although I think the analysis could have more sharply focused on the ideological forces that accentuated the trends being discussed and which are preventing the solution.

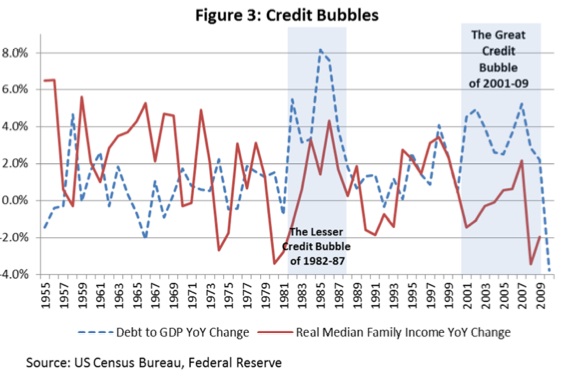

The NAF Report provided this graph (their Figure 3) which contrasts the rising debt burdens with the declinining capacity to pay.

They note that “during the Great Credit Bubble of 2001-2009, real median incomes fell , on both an average annual basis and in the aggregate”. At the same time “Real Household Net Worth soared … but it has since returned to a level last seen in 2000 at the beginning of the bubble period. Never before has the U.S. seen a decadal, or indeed anywhere near a decade of, retreat in real household net worth”.

The NAF Report also asks why the conventional policies used to date haven’t worked? The reasons given are:

1. “Monetary reflation was the principal policy focus in the early stages of the crisis” but while they have “helpfully reduced the debt-servicing burden … they cannot prompt businesses to invest when consumer demand is weak and when global and domestic capacity are more than adequate to supply that which is demanded”. This is also a regular theme of my writing. The reliance on monetary policy reflects the ideological dislike of fiscal policy – simple as that. The reality is that QE(Z) will not stimulate demand.

2. While the “economy is now suffering a dramatic shortfall in global aggregate demand, relative to supply” diffuse aggregate demand stimulus will not work. What is needed is “concentrated, demand stimulation”. I often refer to employment-rich fiscal policies. Trying to rely on what the NAF authors call “diffuse tax cuts and income supports” when the private sector is intent on saving and there is considerable external leakage is not a very clever fiscal strategy.

This is one of the reasons I advocate a Job Guarantee because it directly matches the fiscal outlay with a job. The money doesn’t get spent unless someone turns up at the “JG depot” asking for a job. It is a 100 per cent successful way of matching spending with job creation in a crisis.

Further, given that “businesses can meet any current and medium-term demand without material pressure on wages or existing capacity” it makes no sense to try to encourage further investment until capacity utilisation is closer to capacity.

The NAF authors also note that “Europe and the United States can’t both pursue trade adjustment simultaneously” which makes the IMF pet export-led recovery strategy look like a poor option.

3. Among the other “Non-Solutions” they say “(a)mong the most troubling is the idea of fiscal austerity” which will:

… simply lead to a vicious circle of yet weaker demand, weaker investment, more unemployment, and still weaker demand, ad infinitum – the familiar “downward spiral” of all “great” depressions wrought by the “paradox of thrift.” This is especially true if austerity is pursued simultaneously in Europe and the United States, as now is in real danger of happening owing to European measures that are just as wrong-headed as now-voguish American ones.

Again a repetitive theme in my blog. Any reasonable person would have to conclude that the conservatives (IMF, Euro bosses, US politicians, Osborne-Cameron etc) all know this and are using the beat up claim that there is a “fiscal crisis” to deepen the neo-liberal attack on workers’ rights and trade union power (what there is left of it).

The Tea Party support base probably believe the stories the Republican bosses tell them but they are equally victims of the ruse. Fodder in the class struggle. Did I say class struggle? Isn’t class dead? Not a chance.

4. The NAF Report also rejects those who call for “deliberate monetary inflation” because it would be “difficult, if not downright impossible, to generate wage inflation sufficient

to match asset- and consumer-price inflation, given the magnitude of our current excess reserve of labor both within and without our borders” given the state of the labour market.

5. What about “short-term stimulus combined with long-term fiscal consolidation” which “has emerged as the responsible centrist position in policy and media circles in DC”? They reject that as being “too temporary, too focused on short-term tax relief and consumer support, and too misdirected to provide the economy more than a modest and temporary boost, as opposed to the bridge to long-term restructuring and recovery that the U.S. economy requires”.

A solution?

Finally, what do they propose as the way forward?:

Rather than lurching from one futile mini-stimulus and quantitative easing to another, we must build consensus around a five-to-seven-year plan that matches the likely duration of the de-levering with which we now live …

That is we have to forget all this IMF and OECD nonsense about fiscal consolidation which is kind for growth – that is impossible when non-government demand is flat. We must be prepared to run deficits to support private deleveraging on a more or less continuous basis until private-led growth is strong enough. Given the scale of the debt overhang, a 5 to 7 year time horizon is not unrealistic.

The NAF Report plan is summarised as follows:

1. “Concentrated demand: A workable recovery plan must fill the gaping demand hole currently opened by consumer/private sector de-levering and widened even further by consequent underemployment. It must do so in a way that both creates reliable jobs and contributes to America’s future productive capacity and investment needs”.

So they advocate “sustained and strategically concentrated public investment, not temporary, diffused would-be consumer demand stimulation”.

Green technology development, repairing degraded public infrastructure etc are all areas in which jobs could be created.

2. “Debt-overhang reduction” – this requires that fiscal policy ensure that the private sector can reduce its debt levels and that wage-driven replace credit-driven consumption. THey don’t go as far as saying it but this will require a fundamental redistibution of national income such that real wages growth matches productivity growth”. That effectively challenges the essence of neo-liberalism. It would thus amount to an outright rejection of neo-liberalism.

They also consider “a new program of debt restructuring, refinancing, and in some cases relief – particularly in connection with household mortgages and commercial real estate” is required and “will require creditors to recognize losses and recapitalize”.

In this blog – Asset bubbles and the conduct of banks – I outline a way in which the government can deal with the housing crisis without promoting debt defaults. I will leave it to you to read the detail of their plan which is somewhat different to the way I would deal with the housing issue.

3. “Global rebalancing … to address the deep structural deficiencies and imbalances that have built up in the U.S. and global economies over the past several decades”. This relates to China and Germany being excessive savers and the US and UK being the opposite. I wouldn’t conflate Germany with the others. It belongs to the EMU which has special problems that go beyond any policy to get Germans to consume more.

The NAF Report is fairly general here calling for the US to “help build an international consensus around the kind of reforms China should be encouraged to undertake over the

next five years to facilitate global rebalancing” – that is, to consume more of its own produce.

I disagree with most of their analysis here. I think that advanced nations can see the development of China as an opportunity not a cost. It is an opportunity to reallocate domestic resources to other (better) uses. There are no shortage of productive job opportunities in the US notwithstanding China’s “skewed” development. There is just a shortage of funding. That funding has to come from the government at present given the parlous state of private balance sheets.

I don’t consider it the role of the US to lecture China on domestic policy. In a separate blog I will outline my views on trading with oppresive regimes which deliberately deny their citizens basic rights of assocation. But that is another story.

I also do not support the development of a “World Economic Recovery Fund”. National governments have the fiscal capacity they need to fill private spending gaps. They just shoulod use it. Where a poor nation has to import food and cannot garner the foreign exchange then such a fund might be useful. I have argued before – in this blog –Bad luck if you are poor! – that the IMF could usefully play this sort of role.

But I reject unelected and unaccountable international organisations being allowed to dictate domestic policies of nations just because they provide them with funding (which they got from other nations anyway).

Such a fund is also not the solution to the Eurozone as the NAF authors suggest. The EMU should be disbanded and national sovereignty restored with flexible exchange rates.

Conclusion

The disappointing thing about the NAF Report is that they do not advocate direct job creation schemes. The employment quantum from large-scale public investment programs are unclear and rely heavily on private contractors who always have an incentive to minimise the labour input.

The first thing that national governments should do right now is to introduce a Job Guarantee and then development a range of public infrastructure projects that would dovetail into that scheme (not in an integrated way but in a complementary manner).

I have run out of time …

Tomorrow the Australian Labour Force data comes out and I will be covering that in some detail. I am also giving a talk about MMT and the global challenges at a major national Mining conference tomorrow. I will see if I can provide audio of that talk in due course. I asked the organiser whether he knew what he was in for when he invited me to be the Keynote speaker and he said the industry needed some broader perspectives.

That is enough for today!

I hope the talk goes well. They might not believe a word you say – but if you could leave them with a prediction no one in the mainstream has made, and that you are reasonably sure to come true, six months down the track they could be scratching their heads thinking that you were onto something.

If the commodities bubble blows Australia’s mining sector is going to be in for some major trouble. Are you going to let them know? If you do they might tar and feather you…

Nice to see Nobel Prize economists like Roubini beginning to catch up with what MMT bloggers have been saying for two years. What took him so long?

Roubini & Co claim that “diffuse tax cuts and income supports when the private sector is intent on saving and there is considerable external leakage is not a very clever fiscal strategy.” No, the people who are “not very clever” are Roubini & Co.

It is blindingly obvious that given higher than normal household savings, deficits will have a lower than normal effect. But that is a reason for a higher deficit, not for distorting the economy towards public sector output.

Moreover, most households now know that banks and other mortgage providers in the US are semi-criminal organisations. For the next decade, households will probably SAVE to a greater extent than in the pre-crunch years, rather than take out mortgages. So we might as well get used to it.

As for Job Guarantee, Bill, I don’t agree with making the above distortion even worse. That is, if we HAVE to concentrate stimulus on public sector spending, then what’s wrong with spreading the stimulus over the ENTIRE public sector? What’s wrong with re-employing the teachers, police, etc sacked during the crunch? The output of properly qualified public sector employees, like teachers, is VASTLY superior to the output on make work schemes like JG.

Indeed, as you put it, “We must be prepared to run deficits to support private deleveraging on a more or less continuous basis until private-led growth is strong enough.”

Bill,

You will not have seen the UK (un)employment figures yet; 2.57M or 9.1% with nearly a million young people unemployed (a rate in excess of 20%). No comment from Cameron-Obourne yet but I can garauntee it’ll be along the TINA line with some supply side nonsense. The latter is still evident; the latest wheeze is to threaten to remove benefits from people who are unwilling to travel one and a half hours for a job irrespective of the pay they are likely to be receive (derisory in many cases even if there are jobs to be had).

Despair!

Nice rundown Bill. Thanks.

I really appreciate your comments on the infatuation with monetary policy and aversion to fiscal policy among contemporary mainstream economists and policy-makers. It’s getting worse than ever here in the US. Mainstream Democrats seem to have given up on fiscal policy en masse, primarily for political reasons I think, and are now turning to all sorts of monetarist and supply-side solutions and philosophies, many of which severely misconstrue the nature of the banking sector and overestimate the role of the central bank in stimulating lending, and in controlling price level expectations.

@Ralph,

I think the JG starts to apply once the government is at the right size in order to achieve public purpose (what is seen as public purpose by the people who elected the government). So if the people want more teachers then techers need to be hired. This means that the government needs to offer them attractive wages and compete with the private sector.

The JG onthe other hand is only an automatic stabiliser done right.

So if a teacher gets the boot from a private school for whatever reason, and if the government has already enough teachers to achieve its public service duty, then the guy can go to the JG office and get a job.

However, qualified (and therefore probably adaptable) workers such as this teacher are likely to find an interesting position in the private sector very quickly (because hopefully there would not be a lack of aggregate demand thanks to JG) and not even need to ask for a JG job.

Ralph Musgrave says:

Wednesday, October 12, 2011 at 22:44 “As for Job Guarantee, Bill, I don’t agree with making the above distortion even worse. That is, if we HAVE to concentrate stimulus on public sector spending, then what’s wrong with spreading the stimulus over the ENTIRE public sector? ”

What distortion?

Partha

@Tristan

“However, qualified (and therefore probably adaptable) workers such as this teacher are likely to find an interesting position in the private sector very quickly (because hopefully there would not be a lack of aggregate demand thanks to JG) and not even need to ask for a JG job.”

That’s should be what happens. Contrast this with the reality in the UK where there are at least 10 unemployed people available for each vacancy. The employers have the luxury to choose only those with direct and relevant experience. Given most jobs only require 2-5 years experience to perform adequately, they are far more inclined to choose an experienced 20-30 year old than an experienced 40-60 year old.

I’m saying this as a 50 year old (ex hiring manager) with a consistent work record and high quality resume as long as your arm. I Have no replies for 2 months, despite lowering salary and job expectations to the level I was 20 years ago.

Partha:

I suspect there is distortion involved for the following reasons.

There is no reason to think the OPTIMUM amount to spend on infrastructure varies much from one year to the next, or even one decade to the next, recession or no recession. Thus in most cases, the “infrastructure spending” idea is a knee jerk reaction to recessions, rather than any sort of carefully thought out set of ideas as to what the optimum amount of infrastructure spending is. If Roubini could cite stuff he published five or ten years ago arguing for more infrastructure spending, I’d believe his “more infrastructure” claims. But he does not cite anything of this nature. Indeed, he advocates more infrastructure spending SPECIFICALLY AS A CURE for the current recession. Thus I suspect his ideas come under the “knee jerk” category: i.e. I suspect he is advocating a big increase in infrastructure spending, to be followed in a few years by an equally irrational reduction in such spending. And that all sounds like “distortion” to me.

He also trots out the old argument (p.4) that interest rates are currently at an all-time low, thus governments can easily borrow so as to fund infrastructure spending. That argument is nonsense because governments of monetarily sovereign countries to not need to borrow at all in order to spend. Such governments are not financially constrained: they can create or print any amount of money any time. The only constraint is inflation, as Bill has pointed out a hundred times.That is further evidence of muddled thinking by Roubini.

Another reason for thinking that borrowing costs are irrelevant is that what is called the “golden rule” in the UK (i.e. the idea that governments should borrow to fund investments) is nonsense. That is, as Kersten Kellerman showed in a paper in the European Journal of Political Economy (2007), it does not make sense for governments to fund capital investments via borrowing rather than via tax. Of course when costing public sector investments, some sort of nominal sum in lieu of interest should be added to the cost so as to get a fair comparison with other forms of spending. But ACTUALLY BORROWING to fund such spending does not make sense. Her article is called “Debt financing of public investment….”

Civil engineers have called for more infrastructure spending, they may be biased.

The questions are (assumming MMT is correct), how much deficit spending can a sovereign government do without pushing inflation too high? How much inflation is too high? How do keep the dollars from going almost directly into corporate/shareholder/CEO pockets? How will wages be compensated for by inflation or will inflation outstrip any wage increases (likely given the deflationary environment we’re in)? What about the immobililty of househoulds to move where the jobs are due to upside down home mortgages?

It seems like many see MMT as a panacea for all of the ails of society, but it just isn’t.