I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Australian retail sector in recession

Everywhere I walked in Melbourne last Saturday there were sales. Signs emblazoned all over the front of shops advertising 30 per cent, 50 per cent and 70 per cent discounts. The only problem is that I see those signs all the time now whenever I go retail precincts. The annual sale concept is now a continuous effort to rid stores of excess stock as consumers go on strike. So what is going on? The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) released the June 2011 – Retail Trade data today and in showing that retail sales have contracted for the second consecutive month they confirmed what we already knew from the empty shops and sale signs – the retail sector is now in recession and things are getting worse.

The highlights for the Retail Sales for June 2011 were as follows:

- In current prices, the seasonally adjusted estimate for Australian turnover fell 0.1 per cent in June 2011 following a fall of 0.6 per cent in May 2011. So the Retail Sector is now in recession – two successive months of negative growth.

- Unadjusted data shows that total Australian turnover fell 0.8 per cent in June 2011 (large retailers down 0.5 per cent and smaller retailers down 1.2 per cent).

The Sydney Morning Herald report (August 3, 2011) – Retail sales post surprise fall in June – claimed that the fall was unexpected. I guess the reporter only talks to the bank economists (they were the only ones quoted in the article) who are always predicting growth will be excessive and interest rates will be going up.

Yesterday the August meeting of the RBA scotched those predictions by holding the interest rate constant. The last time rates rose was in November 2010.

The reality is that there are no demand pressures driving inflation at present and the retail sales figures suggest consumers are truly moderating their spending patterns after a decade or more of bingeing on credit and building up record levels of household debt.

The Sydney Morning Herald analysis (August 3, 2011) – Food inflation puts shine on gloomy retail figures noted that:

… discretionary retail on the whole is suffering not just from low consumer confidence but low consumer interest, meaning consumers are responding lethargically even to deep discounts … the soft goods business is in an abject state with both the specialty and department store channels experiencing tanking sales. Although data for the online retailers is unavailable it is likely that this is the only soft goods channel currently above water … the supermarket chains are making deep inroads into the market share of independent food operators. This poses a material threat to the rental growth of small shopping centres, which depend heavily on independent perishables retailers.

The following graph shows the Retail Sales since January 2008 (in $A millions). The trend is a 6-month moving-average. The first fiscal stimulus payments to consumers was in December 2008 which was followed by the $A42 billion stimulus announcement in February 2008.

If I was looking for a single piece of evidence that the fiscal intervention increased retail sales I couldn’t find a better graph to demonstrate that.

The stimulus clearly boosted spending during the period that it was concentrated as the graph indicates (the significant above-trend retail sales). In doing so, it not only replaced some of the declining private demand but also gave households extra financial capacity to both spend and increase their saving ratio. The data shows that both impacts have occurred in the last year.

So the fiscal expansion provided support for aggregate demand and helped prevent the labour market from totally melting down (it is still bad) but also provided the space for the household sector to increase saving as well as spending because it supported income growth (via the demand impact).

At the time, the conservatives claimed that the fiscal stimulus would not be expansionary because the household sector would just save it all. But that seriously misconceived the way spending stimulates income which in turn stimulates saving.

It was never going to be an spend or save situation. That is the beauty of fiscal policy – you can have both.

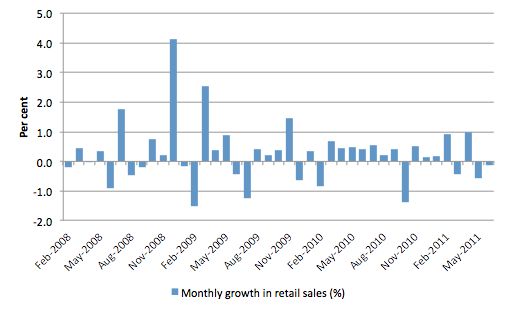

You get another excellent view of the impact of the fiscal intervention from the next graph which shows the monthly growth in Australian retail sales over the same period as specified above. The two large positive spikes correspond to the impact periods of the fiscal stimulus.

The issue of retail sales is interesting in Australia at present because it signifies a development that has not previously been discussed widely in the public debate. The evolution of the Internet is changing the structure of industry. A major report “commissioned by search engine giant Google Australia” was released in Australia yesterday and found that (Source):

… the internet economy was worth about $50 billion in 2010, 3.6 per cent of gross domestic product, and was forecast to rise to $70 billion over the next five years … [this] … was half of the powerhouse mining sector’s contribution to GDP last year, and just $3 billion less than the retail sector’s share … the total economic benefit of the internet to the wider Australian economy stands at about $80 billion – including productivity gains to households and businesses.

What the study did not reveal was “how much of the growth in the internet economy is at the expense of other Australian industries”. The news story about the Report notes that its release:

… comes in the wake of months of job losses, store closures and sales dives at so-called ”bricks and mortar” retailers, whose woes have been blamed primarily on weakened consumer confidence, but also on growth in online shopping, exacerbated by the strong Australian dollar.

There is no doubt that the Australian consumers are very cautious at present and are clearly trying to deal with the record levels of household debt that followed the credit binge in the decade leading up to the financial crisis. The withdrawal of the fiscal stimulus and the persistently high labour underutilisation (unemployment and underemployment) have combined to drain the confidence of consumers.

But there is another trend developing which is very interesting. This relates to what is known as the Dutch Disease. Please read my blog – A rising public share in output is indicated – for more discussion on this point.

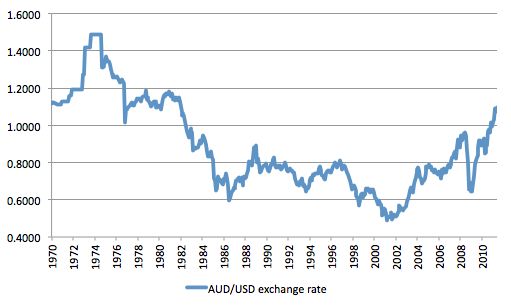

Even though there was a sell-off overnight of the Australian dollar (AUD) as a result of the RBA’s decision to keep interest rates on hold yesterday, the Australian dollar has sky-rocketed in price in the last year.

The Australian dollar was finally floated in December 1983 after the Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange collapsed some 12 years earlier. There was a very conservative approach taken in Australia – as always (to our detriment).

The following graph puts the current parity (the highest since the float) in historical perspective – it shows monthly data for the AUD/USD parity since January 1970. It confirms the roller coaster life we lead here in terms of our exchange rate – around ten years ago my American mates used to call us the “half-price shopping centre” (in March 2001 the rate was as low as 48.9 US cents). The smile is on the other face now as we buy 1.10 USD per AUD. At least if you are not receiving any USD-denominated income!

But while an appreciating currency is anti-inflationary (reduces the prices of imports in local currency) it also promotes structural imbalances. When a currency is appreciating, you get sectoral effects with the traded-goods sector which is what the term Dutch disease refers to.

One part of the traded-goods sector might be enjoying booming demand conditions on international markets (high terms of trade) while the other parts of the traded-goods sector are not enjoying an exogenous demand boost.

The booming terms of trade overall reduce the competitiveness of all traded-goods activities but the former sub-sector can overcome the reduction in competitiveness as a result of the booming demand for their products. However, the other sub-sectors which do not enjoy the exogenous demand boost suffer.

The Australian version of the Dutch disease typically that mining booms and pushes the dollar up but the same global demand bouyancy is not enjoyed by agriculture anf manufacturing (both who also export). The latter two are then disadvantaged by the higher foreign price for their exports but no change in domestic (AUD) costs.

In Australia at present, the mining sector is strong because world demand is high for base metal commodities and this has had the effect of pushing the AUD upwards. However, other exporting industries (for example, manufacturing and agriculture) are not enjoying the same bouyancy in demand for their output but have to face the terms of trade impacts on their margins of the exchange rate appreciation.

At least this has been the historical version of the Dutch disease and there is no doubt that it has been relevant. But there is now a new trend emerging as a result of the growth of the Internet.

The poor performance of the retail trade sector over the last year or so is being blamed, in no small part, on the increase in on-line shopping. What this conjecture effectively means is that the retail sector, which has traditionally been part of the “non-traded” goods sector and therefore not part of the Dutch disease dynamics is now part of the traded-goods sector.

With on-line access cheaper and more pervasive and the exchange rate so high in relative terms shopping on-line is now very attractive. The local retailers have been very reluctant to develop on-line capacities thinking that the combination of having to wait for the goods and services to be posted, the lack of ability to sample the goods directly (check fit etc) would be sufficient to discourage a major trend away from personal shopping.

The local retailers have also taken advantage of cheap imports (particularly clothing) and placed obscene mark-ups on them at the retail level. Consumers were held to ransom by this profiteering behaviour. Now we can buy the goods directly at low prices and by-pass the mark-up. So to some extent the local retailers are to blame for their own demise.

There has also been mis-placed protection on many goods (books, CDs etc) which has been justified by the industry as providing a secure path for local authors and musicians to gain popularity. The evidence appears to support the fact that the producers don’t benefit much at all (authors, musos) and the publishers and record companies etc have been pocketing the higher prices. Now we can get books and music easily delivered to our door through the Internet at very low prices compared to what the same product sells for locally.

The appreciating exchange rate has made this even more obvious.

The latest data supports this conjecture. Food retailers are still performing well because it is difficult to purchase food on-line. The areas of retailing that are being affected by the “Dutch Disease” are textiles (clothing and footwear) and books and publishing.

So the retail sector is definitely suffering because cautious consumers are now trying to reduce their debt exposures after a decade or more bingeing on credit while still fearing a double-dip recession coming from fiscal austerity.

But on top of that technology and the exchange rate appreciation is creating changing patterns of consumer behaviour which also predicate against local retailers.

There was an interesting speech last week (July 26, 2011) by the Governor of the Reserve Bank of Australia – The Cautious Consumer – which didn’t receive as much analysis as it should have. The Governor noted that even though “Australia is in the midst of a once-in-a-century event in our terms of trade … we are, at the moment, mostly unhappy. Measures of confidence are down and there is an evident sense of caution among households and firms. It seems to have intensified over the past few months”.

The RBA Governor provided the following graph (derived from the National Accounts) which shows “the level of household disposable income, and household consumption spending” in “real per capita terms, and shown on a log scale”. The “lower panel is the gross household saving ratio, which is … the difference between the other two lines expressed as a share of income.”

The trend lines are also shown for each series in the top panel estimated up to 2005 and then extrapolated after that. The point is that trend consumption outstipped trend income growth between 1995 and 2005 (income grew at 2 per cent per annum and consumption at 2.8 per cent per annum). In the two decade prior (1975 to 1995) the growth in consumption was around 1.8 per cent per annum.

The manifestation was the sharp drop in saving as a share of income.

The Governor now considers this trend to be over – and the age of the cautious consumer to be upon us. Which spells trouble for retailers who had geared up on the basis of the credit-fuelled binging that defined the 1995-2005 decade.

He noted that the period from 1995-2005 also saw a doubling of the real per capita wealth relative to the previous four decades and a “large part of the additional growth was in the value of dwellings” with “leverage against the dwelling stock” rising significantly.

He said that this period was “unusual” and the trend became much flatter in 2008 and since and that this “roughly coincided with the slowing in consumption spending relative to its earlier very strong trend.”

His assessment of these developments is as follows:

The period from the early 1990s to the mid 2000s was characterised by a drawn-out, but one-time, adjustment to a set of powerful forces. Households started the period with relatively little leverage, in large part a legacy of the effect of very high nominal interest rates in the long period of high inflation. But then, inflation and interest rates came down to generational lows. Financial liberalisation and innovation increased the availability of credit. And reasonably stable economic conditions – part of the so-called ‘great moderation’ internationally – made a certain higher degree of leverage seem safe. The result was a lengthy period of rising household leverage, rising housing prices, high levels of confidence, a strong sense of generally rising prosperity, declining saving from current income and strong growth in consumption.

Yes, the period of aggressive financial engineering and consumption being driven by credit rather than real wages keeping pace with productivity growth. You will notice that he didn’t mention that there was a fundamental change in the distribution of income during this period away from wages towards profits. The only way consumption could grow so quickly was via credit.

He admits that this period “was bound to end” and that the private debt spiral ends and “the rate of saving from current income will rise to be more like historical norms, and the financial source of upward pressure on housing values will abate.”

The interesting part of the speech was then his evaluation of the “implications of these changes”.

1. “the role of the household sector in driving demand forward in the future won’t be the same as in the preceding period”.

2. ” the rise in the saving rate over the past five years has been much faster than its fall was in the preceding decade. In fact it is, at least as measured, the biggest adjustment of its kind we have had in the history of quarterly national accounts data”.

3. “Will the ‘good old days’ for consumption growth of the 1995-2005 period be seen again? I don’t think they can be, at least not if the growth depends on spending growth outpacing growth in income and leverage increasing over a lengthy period”.

4. “the level of the saving rate we have seen recently looks a lot more ‘normal’, in historical perspective, than the much lower one we saw in the middle of last decade”.

5. “If we want to sustain the rate of growth of incomes … we will have to look elsewhere”.

He then claimed that this all points to the need to overcome our poor productivity growth. But another essential condition for sustainable growth is to ensure the growth in income is distributed more evenly (such that workers gain real wage increases in proportion to productivity growth. That has been sadly missing in the “debt decade”. He ignores that “class” issue.

But the other point that he ignores in his assessment is that if consumption is falling back to its historical norms then other spending aggregates which have been abnormal during this period will have also resume historical norms unless there is a fundamental structural change.

What do I mean by that?

Australia has long enjoyed a current account deficit where foreigners have been willing to send us real goods and services (capital equipment and consumer items etc) in exchange for financial assets denominated in AUDs. So the real terms of trade (what real resources we have to send them relative to the real resources they send us) has long been in our favour.

But this means that the overall impact of the external sector is to drain aggregate demand (import spending greater than export revenue) and place a drag on growth. In the period 1996-2007, the conservative Government ran surpluses 10 out of 11 years. These surpluses were only possible because the consumption spending was so strong on the back of the abnormal credit binge. Historically, the government runs deficits to ensure that aggregate demand grows strongly in the face of the external deficit and private domestic saving.

So if households and firms are not going to borrow as much unless the external sector becomes a major contributor to growth, the obsession with budget surpluses will have to change and governments (and all of us) will have to be comfortable, once again, with continuous budget deficits at the federal level. The RBA Governor avoided teasing that implication out of his analysis – for obvious (ideological) reasons. But that is the future we face.

Conclusion

That is enough for today!

“unless the external sector becomes a major contributor to growth”

Pascoe, Stutchbury and the rest of the boggle eyed, hyperventilating econo-press are absolutely convinced mining boom II will literally drown the country in money. Will it or won’t it? I’d love to draw Bill out to have a punt on this one.

Interesting that the Australian experience is mimicking the experience here in the UK. Our Exchange rate against the rest of the world shot up in 1997 and collapsed back again in 2007. That also resulted in the few remaining textile firms closing as their export markets dried up, and of course we got the Internet revolution in the middle of that which has totally destroyed the bookstores and record shops of old.

Although I think the UK ‘primary export’ at the time was a government induced Property Bubble.

“What the study did not reveal was “how much of the growth in the internet economy is at the expense of other Australian industries”

I think online shopping only accounts for around 2% of what would ordinarily be goods sold be retailers Bill.

In the UK (and I suspect the US) it’s hard not to feel profoundly depressed.

We have had a supposed boom – “the great moderation” – that was actually a massive boom for the rich and stagnation for the rest, paid for by an unsustainable credit boom. Essentially the financial sector decided that the cure for stagnating profits was to bring forward future consumption (credit) and bring forward future profits (financialisation). All of this went to the top 2% while the rest of us were drugged by easy credit into thinking that we were better off.

First the Thatcherites spent the oil money on tax cuts. Now, unless policy changes, we have donated our future public services to the bankers.

But how to get out of this mess? Personal expenditure is bound to consolidate in order to unwind the credit bubble. So only by a sustained investment in tangible industry (you only have to look at what Germany is doing with sustainable energy to see a lot of potential) and public infrastructure can take it’s place.

But what will we get? The financial sector has very successfully moved the discussion onto an obsession with the 3Ds: debt, deficit and default. This will only mean the further destruction of the public sector and, at best, stagnation.

The question is. Where does the (vampire) financial sector think the next round of profits are going to come from? We are already seeing a move into commodities – destabilising prices. Who will be the next victims?

@ gastro george

When the economy gets worse as it invariably will, we will see greater public disorder.

It either triggers a policy reversal or the right wing will start developing a police state and cook up a few wars.

It’s tempting to say that we are already seeing the next financial victims, as the great vampire squid circles the Euro economies and any other country that it can threaten with the burning white cross of default.

Don’t forget that Germany appears to be booming only because it is sucking Euros out of the rest of the Eurozone.

Domestically it doesn’t have the consumption to prop up its workforce.

Bill –

A few weeks ago the big chains were blaming the growth in online retail on the fact that consumers don’t usually have to pay GST on overseas purchases

Do they have a point?

Do you think their proposed solution of extending GST coverage work?

Would abolishing the GST be the best solution?

A bit off topic, but may be of interest …

A conservative MP Sajid Javid has just been interviewed on the BBC radio 4 PM programme. He has put forward the view that there should be a limit, by law, on the level of debt the UK may have. He suggested 40% as a possible value. If a government exceeded the limit then, by law, they would have to buy government debt to get down to the max allowed. Presumably by cuts to expenditure.

I find it very worrying that there is so little in the media in general that might show this type of view is so wrong and will reek havoc with this country’s development. There is another radio4 programme at 20.00 (BST), Keynes v’s Hayek. I wonder just how interesting it will be?

“There is another radio4 programme at 20.00 (BST), Keynes v’s Hayek. I wonder just how interesting it will be?”

My first inclination was to respond that it would be a parody with the usual sock puppets appearing. But Paul Mason is not a bad journalist. He is, at least, interested in real people, and has run some good stories on Newsnight, for example about the effect of the recession in places like Detroit. Duncan Weldon is also worth following, as he has his heart in the right place and will at least listen to MMT arguments.

I shall be in the pub, but I’ll try to listen to it on iPlayer tomorrow.

Aidan

Firstly, I don’t think changing the GST coverage will happen because the cost of collecting the GST would outweigh the GST collected and in these auster times that is a no-no.

Secondly, the savings by shopping on-line are more than the GST. On our Local ABC radio station on a Tuesday night they have a panel of advertising and martketing experts. They have been talking about this isssue recently. Convenence and service appears to be playing a big part. The choice is I sit at home at my computer and shop on-line, or do I get in my car go to the shopping centre, find a car park (possibly in the future pay for that car park), make my way through the crowds, to go into the shop that I want where I am treated with indifference or even contempt by the sales staff.

I beleive that the problem is structural.

We have gone from shopping at strip shops and small local shopping centres to shopping at large highly geared, listed corporate shopping centres. These large centres provide low rents to the anchor stores (Woolworths, Coles, DJs, Myer) to bring the crowds in. It is possible to understand from the prices in Woolworths Catalogue. But then they need to charge higher rents on the other stores to recover the subsidy, as well earn sufficient returns to satisfy the shareholders, and the bankers’ LVRs. They also require the tenants to undertake expensive refits, whether the store requires it or not, every 3 to 5 years. The non-anchor stores therefore, have a very high overhead, and have probably also borrowed heavily for the fit out. They then pay low wages because that is all they can afford, and therefore, get low skilled sales staff who provide a low level of service to the customer.

Under competition caused by the internet, and the high $A this structure is breaking down. Those shops that will survive will probably be those in or who re-locate to strip shopping precincts who use the reduction in their overheads to employ staff with the skills to service their customers and give them something they cannot get over the internet – an experience, a personal interaction with a human.

Aidan, the complaints about gst are just a red herring, as the savings for buying online are generally much larger than 10%. 50% or more is common, and this is still a retail price. I’ve friends who have been buying online for years now due to this. Even with the au dollar at 60 cents it was still worthwhile to buy online for many items.

Bill is correct about the markups, we’ve been price gouged on many goods for decades and the internet is laying this bare, and we can now take advantage of the arbitrage the likes of Gerry Harvey have enjoyed for years. Maybe even commercial property owners will have to do the unthinkable, and drop their rents if they want to retain tennants in future.

The other thing that Neil Wilson touches on is the property bubble, which is where pretty much all that extra debt has come from over the last decade, I’m sure the huge size of contemporary mortgages is sucking spending power out of the hands of many consumers. If 50% or more of your disposable income is going into the mortgage every week, that doesn’t leave much to spend on over priced footwear etc.

Nealb, do you think there will be a trend away from megamalls back to more traditional strip shopping, or more stand-alone stores in future? It occurred to me the other day, when I was in a Westfields, they must be very energy hungry expensive places to run, with the need to light, air-condition, clean and maintain those huge internal spaces, costs that end up on the price tag, and costs that older style or online shops don’t have.

Another thing, subjectively I wouldn’t mind seeing the end of the huge shopping mall, I think they are a bit of a blight on the landscape, and i hate the moncultural nature of the things, they are the same with mostly the same stores wherever you go in the world.

Hamish

The more I think about it the more I think that the trend will be back to the traditional strip shopping and stand alone stores. Whilst people have been saying that for years and it hasn’t happened yet, I hink that there are underlying currents that will eventually cause it to happen.

Those currents are:

– As you pointed out energy requirements. As energy becomes more expensive and it will become costly to air-condition the common areas. A cost that strip shopping does not have. However, the contra is that strip shoppers have the elements to contend with but that is the trade off. Also, which you are going to use more fuel with. Driving to your local Westfield, and drive around for ages looking for parking, when the trip to your local strip shop is likely to be shorter (and in some cases you are likely to walk or even cycle) and easier to find parking. Also, the increase in energy costs due to China and India’s middle class will see the West return to more traditional lifestyles – working and shopping locally, and as such pre-War suburbs (cities that became cities before the War) are likely to do better because they were laid out before the wide spread use of the MV, that is it has strip shopping, offices for professionals (local accountant/lawyer/doctor), and has reasonable public transport.

– The financial structure, and power of the Westfield’s etc is such that rents are sticky on the downside, and more elastic on the upside. The gearing of the owner’s of strip shops can be an issue. However, if the shop owner is an owner-occupier then this is less relevant. However, the ownership of a strip shop can be more quickly changed then a mega mall.

– The culture of the large shopping mall. The thing that I hate most is probably when my wife says we need to go the Westfield – parking is usually an issue unless you get there very early, finding your way around the centre can be hassle (particularly in the days when a pram was requried for the kids) and usually it requires a visit to the food court. I go to the local strip shops if I need a haircut or to see a doctor. I get bread at a local bakery, and if I have to go to a grocery shop I go to a Foodworks/IGA or a standalone store.

I guess that we will have to wait and see but I think that we will be closer to an answer in a year or two, when this current downturn really bites, and shops start emptying in these mega malls putting the owners under financial pressure.

Hamish

Retailers in megamalls also face additional costs that strip shops do not:

– Wages for low volumne periods. Retailers in the mega malls usually have their hours setby the cente management. So if a particular period in the week a shop consistently experience low or no sales, they cannot decide so close the shop during that period. They have to remain open and run at a loss.

– Outgoings. Landlords usually pass on thier outgoings to the tenants. Outgoings are things like building insurance, rates, air-conditioning. Upto until about 5 years or so ago (it could be longer) the position in Qld was that landlords could not pass on Land Tax to the their tenants, but now they can. So not only are there the energy costs of the common areas, there are the statutory charges for those areas that must be paid, which I am sure councils and state governments will increase in their chase for more revenue.

Australia has been very well supplied with shops for many decades. People who have operated shops overseas often comment on the low number of potential customers for each shopping centre. I think that the contraction of the retail sector was inevitable.

Centres like Chadstone will survive because there will always be aspirational shoppers who want to see what’s in the shops and shop with their friends, think 15 year old school girls. Department stores had had their day by 1992 when the Yannon scandal erupted and Myer had to chose between keeping their department stores or their shopping centres.

Nealb, I’ve read of extra costs tennants incur in the mega malls, I’ve even heard that Westfields takes a cut of your profits.. so what you say doesn’t surprise me, and makes me think even without energy price increases, it’s a style of retail that may not be cost competitive anyway, too many hands trying to take a cut.

Running a small retail shop in a Westfields sounds like a pretty crappy deal to me, with them dictating so much of what you do. I thought part of the reason for running a small business is having more control over your destiny.

Anyway, be interesting to see how this pans out.

Isn’t it amazing the retailers woes are being blamed on the unproductive workforce and excessive regulation. Some more, they are only squealing over squeezed margins, not even talking about making a loss.

The consumer is squeezed every which way. On the cost side there is a tremendous overhead from inflated land prices and sky high rents. Money for nothing, the rent seeking activity of non-productive banks and landowners. Then we have retailers with distribution monopolies price gouging. Then we have Coles on every street corner, tempting us in with cheap milk and charging crazy prices for everything else.

Its always the workforce fault, no questions about it from the press. Makes you want to puke.

On another note I see the toll road operators have boosted their profits too. What bright sparks thought an unregulated monopoly of key transport routes was a good idea?

Apparently 65% of Australians think these types of private/public partnerships are the way to go.

More toll roads…… woo hooo …..Turkeys…Christmas! anyone?

Gastro,

Duncan Weldon doesn’t have a lot of time for government intervention. He comes from the central bank side and is constantly pushing the supply side arguments. I found his attempt at criticising MMT lightweight at best.

It’s difficult to know whether that’s what he believes or whether that’s just what plays well in whatever political career he has his eye on in the Labour Party.

I actually see the “Let’s just tweak the system a bit with a few green investment banks” people as part of the problem.

Neil, maybe I’m just grasping at straws as it’s so difficult to hear any intelligent voices. I guess what I was saying was that at least he recognises the problem (lack of demand) rather than deny it.

Speaking of denial, the Hayek vs Keynes radio programme was just an essay in posturing, as you might expect. The Hayekians strike an odd posture. Other-worldly, in that they would let the banks fail – with all the economic catastrophe that might have led to. Contradictory, in that they insist that the solution was not to get into the problem in the first place, while punting free market nostrums that directly led to the problem. Denial, in their insistence that the solution to the Great Depression had nothing to do with Keynes.

Hamish and nealb –

I think you’re underestimating Westfield – it’s very good at filling its shopping centres up. If it has to reduce rents to do so, it will. Increasing fuel costs will be a factor in Westfield’s favour, as the bus routes converge on their malls, and with more people going there by bus, finding a parking space will cease to be a problem.

I very much doubt human interaction is an important reason why people buy things in shops rather than online. There are certain classes of goods (like shoes) where expert sales staff are important but for the vast majority of the stuff we buy, it’s trivial. The reason it’s usually better to buy things in shops is that it’s usually more convenient, and we can get everything instantly rather than having to wait ages for delivery.

And if you can save 50% off the shop price by buying online, you’re probably looking in the wrong shops!

I think the retail downturn is due to more than the economy. First, a complete disinterest in adding more junk to the house they never use. No one dresses up anymore, life has become more casual. Baby boomers have the cash but are wanting to clear out the junk – and that includes clothes they don’t need and have few places to wear, or anything else they have eg how many candle holders can one use? Additionally, people value experiences , like travel, not more dresses like the ones you already have and don’t wear. Many people wear uniforms to work and spend weekends in things and running shoes. Don’t believe me? Go to any Westfield and have a look at people’s feet and their casual clothes. Restaurants are now more like eat in cafes, fostering and catering to people’s attitude they are their to eat , not for an evening out. The days when you got dressed up to eat are almost gone. Second, internet purchases on retail isn’t in retail purchases themselves but internet services that decrease the need to go to shops which reduces the flow of people to shops. All bills can be paid on line which means people don’t have to go to banks, insurance companies, you even have to go to the RTA to register your car. Hell , you can even reserve a library book on line and buy airline tickets and book accommodation on line. No wonder shops are empty.

Second, people are getting bigger , so cant fit into many expensive clothes. Third, as people are wearing cheap clothes, the retailer can’t make the margins they did before on the so called “designer labels.” Factor in the fact that rents are based on return for property investment and not tenant affordability. This situation is promoted by the never ending number of people who decide to go into a business they don’t know , without any knowledge of cash flow, demographics or accounting procedures who enter a lease based on the assumption that the rent must be affordable ” because others seem to manage” when in fact the ” others” are in so much debt they take out equity loans using all the savings they have put into their homes and then cant sell the business they because the purchase price doesn’t pay off their mortgage. So they hope the universe takes care of them, and it does- they eventually can’t pay the rent and stock and get locked out by landlord or are put into liquidation. Then, another ill-informed hopefull comes along with a redundancy payout, an inheritance or a partner to subsidise them unit they bite the dust! I hate to see people getting into financial difficulty but also think large shopping malls have been a curse on society. Malls have destroyed the viability of a person buying a business in many strip centres. People like to spend their time walking around malls, getting fat, spending all their money and they call it entertainment. Get outside, have a picnic, have friends around for lunch, play tennis- that’s what I suggest! You don’t need a new lounge, get a dog. Get a life! If you shop at a local fruit and veg and a butcher instead of entering a supermarket you will save money regardless of the price because you wont buy goods you don’t need and probably won’t be as fat.