I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

The financial press mostly reinforces the lies

I have always been sceptical of the way the US Congressional Budget Office computes its structural deficit decomposition – that is, separates out the cyclical effects (the automatic stabilisers) from the underlying policy settings. I have written about that before. This came back to my attention span again today after I read a column in the New York Times (July 10, 2011) which reported that an “extraordinary amount of personal income” for Americans is now “coming from the US government”. That combined with a really stupid Bloomberg editorial yesterday (July 11, 2011) led me to investigate further. What I found hardly surprised me but reinforced how the American people are being let down by their leaders with the financial press mostly reinforcing the lies.

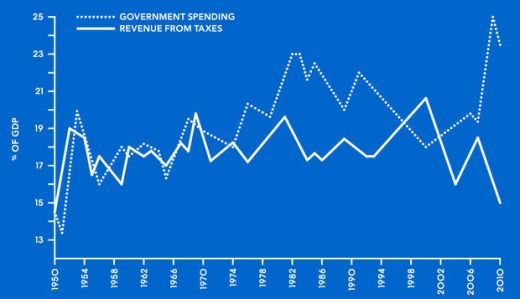

The Bloomberg editorial – Follow the Lines to Budget Truths was just a simplistic attempt to suggest that the US Congress needs to cut spending and raise taxes. They presented the following graph (from 1950 to now) which shows the evolution of US federal government spending and taxation and is meant to substantiate their case.

I have to say the best thing about the graph is the colouring. Not much else is of interest to me in it.

But for the Bloomberg editor it solves the mystery. In discussing the “hybrid budget/debt-ceiling negotiations between President Barack Obama and congressional leaders” (where leader now means something less than it used to mean), the editor says:

Every so often, graphics can speak louder than words, and to that end we suggest a quick look at this chart, using data compiled by Bloomberg. It puts in stark perspective the imperative mentioned by Obama and underscores that, on this issue, he is solidly in the right.

The chart’s solid line — the jagged mountain range in the foreground — shows that income taxes, as a percentage of gross domestic product, are at 14.9 percent, the lowest since 1950. The average in the last 60 years has been closer to 18 percent. It is not hard to look at this line and think, as the president and Democrats do, that it will be tough to solve our budget problems without raising taxes.

First, I am not sure what they mean by “compiled”. The data presented is freely available from the US Office of Management and Budget as well as other sources so I wondered how Bloomberg could claim to “compile it”. But that is only a small point.

Second, in 1950, total US federal revenue was 14.6 per cent of GDP. But between 1950 and 2008 it averaged around 17.9 per cent. The average from 2009 to 2011 has dropped to 14.4 per cent. The recent decline is not a structural shift.

Third, the statement “it will be tough to solve our budget problems without raising taxes” is highly misleading notwithstanding the false assumption that the US problem lies in an excessive budget balance. The budget is a problem – the deficit is too small relative to private spending. The evidence for that statement is the entrenched and worsening unemployment.

At present the CBO has the real GDP gap at average 6.1 per cent (of potential output) although the way they construct that measure it is almost certain to be an understatement of the true gap.

Please read my blog – Structural deficits and automatic stabilisers – for more discussion on this point.

But if we accept the figure for the sake of comparison, the average gap (even with the earlier and sometimes severe recessions included) for the period 1962 to 2007 was -0.3 per cent – that is, relatively small. By comparison the gap between 2008 and 2011 is averaging 6.2 per cent – that is, relatively huge.

So if that gap closes back to the long-term average the revenue side of the US budget will increase dramatically (relative to now) and get back towards the 18 per cent of GDP mark. The deficit terrorists have been trying to argue that since 2000 the revenue side of the US budget has been “structurally weakened” by tax cuts. The average between 2000 and 2008 was 17.9 per cent of GDP, not that much below the long-term average. So the structural deterioration argument doesn’t hold.

I decided to investigate a bit further and ran some regression models. I won’t go into the detail but the results will be easy to replicate using the public data and standard techniques. Even a relatively simple model structure gives good enough results to make the point.

If you regress the revenue as a proportion of GDP on a constant and either the CBO real GDP gap or actual real GDP growth taken from the BEA and then forecast what the outlays proportion would be if the real economy (however measured) resumed its 2000-2008 trend performance what you find is hardly surprising.

I used dummy variables in the model to control for the Clinton surpluses and the Global Financial Crisis which are outliers in the data. Their inclusion makes the estimates more robust but doesn’t alter the cylical sensitivity coefficient (the parameter that tells you how much Revenue as a proportion of GDP changes when the real GDP measure changes by 1 per cent).

The results show that Revenue as a proportion of GDP returns to 17.92636 per cent using real GDP growth and 17.9693932 per cent using the CBO real GDP gap measure. In other words, most, if not all of the decline in tax revenue at present is cyclical.

What that means is that if you really want to increase federal revenue you should be fostering growth rather than trying to increase tax rates.

The automatic stabilisers will generate more tax revenue if growth occurs but if the government increases tax rates it will certainly slow down economic growth which will lead to a further decline in tax revenue.

What about the dotted line in the Bloomberg graph? They say in that regard:

The graphic’s dotted line — the higher altitude range with the plateau — sheds light on another side of the Washington debate. This graphic shows federal spending as a percentage of GDP since World War II. It is not hard to look at this line and think, as the president and Republicans do, that it will be tough to solve our budget problems without cutting federal spending and making changes to runaway entitlement programs like Social Security and Medicare.

Once again the graph doesn’t suggest that to me at all. The average outlays as a per cent of GDP between 1950 and 2008 was 19.8 per cent. From 2000 to 2008 it was 19.8 per cent (so no discernible increase in the scale of outlays). Since 2008 the ratio has been 24.7 per cent as the graph suggests.

Is that increase a structural or a cyclical event? The deficit terrorists and this Bloomberg article are trying to claim it is a structural change in policy.

So if you run the same sort of regression (using Outlays as a percent of GDP as the dependent variable) then the results show that Outlays as a proportion of GDP returns to 20.397505 per cent using real GDP growth and 20.5356493 per cent using the CBO real GDP gap measure. In other words, most, if not all of the rise in outlays as a proportion of GDP at present is cyclical.

Further, if the US governments cuts its spending now – with private spending so weak – then it will almost certainly reduce the growth rate and the ratio of spending to GDP will probably (almost certainly) rise. If they really want to reduce the size of the public sector relative to the economy then the best (and only reliable) way to do that is to increase the size of the economy – that is foster growth.

To increase the real growth rate and reverse these cyclical changes in the budget balance requires – at present – a larger budget deficit not a smaller one. And what we know from experience and the sort of analysis I have presented here is that – a larger budget deficit begets a smaller one if it promotes growth.

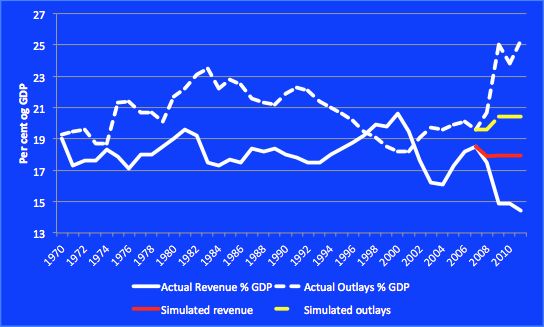

To show the graphical impact of the forecasts I produced the following chart. It reproduces the actual US budget data but from 2007 forecasts revenue and outlays as a per cent of GDP using my regression models – that is, removing the cyclical fluctuation from the data. It is a very rough indication of the structural balance.

The colour is a bit “lairy” but the extra lines are now simulated outlays (red) and simulated expenses (yellow dashed). What do we make of that? Well it says that if the real economy had have performed up to its average between 2000 and 2008 the budget aggregates would have followed the red and yellow paths. The deviation between those paths and the white paths after 2008 is all due to the major slowdown in real output growth.

Further, the implied budget deficit is a bit over 2 per cent of GDP which when compared to the average balance over the period 1950-2008 of 1.8 per cent is about on trend. That size budget deficit normally (when private spending is stronger) is about right to maintain strong growth and high levels of employment. The deficit will have to be a little larger these days because the external sector records larger deficits than in the 1950s and 1960s etc.

So the Bloomberg conclusion:

The president and leaders in Congress have pledged to keep talking. All those involved say that they want to cut the deficit and bring our long-term debt under control. The specifics are in flux, but the general outlines are as clear as the above graphs: Any viable plan will require spending cuts and tax increases both.

…. is an erroneous waste of space. The general outlines in the graph are only clear to those who understand how these lines dance to the business cycle. There is no recognition of that in this editorial. In that sense it is a fabrication of reality. Even mainstream economists know that the budget balance is cyclically-sensitive.

Of-course, all this tinkering with numbers might lead you to think that we should care about the budget balance. We should not! The analysis is presented to provide insight into how the financial media distorts the debate by manipulating meaningless numbers to scare the general public.

The Bloomberg editor should have read the New York Times

New York Times yesterday (July 11, 2010) – Economy Faces a Jolt as Benefit Checks Run Out – bears directly on the topic today.

The NYT article began with this statement:

An extraordinary amount of personal income is coming directly from the government.

Close to $2 of every $10 that went into Americans’ wallets last year were payments like jobless benefits, food stamps, Social Security and disability, according to an analysis by Moody’s Analytics. In states hit hard by the downturn, like Arizona, Florida, Michigan and Ohio, residents derived even more of their income from the government.

By the end of this year, however, many of those dollars are going to disappear, with the expiration of extended benefits intended to help people cope with the lingering effects of the recession.

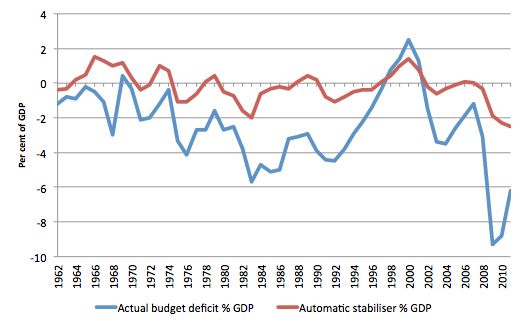

The CBO estimates the automatic-stabiliser component of the budget balance at present to be of the order of 2. 3 per cent of GDP (deficit) in an actual budget deficit of 8.8 per cent of GDP. My own modelling suggests that cyclical component is much larger as discussed above.

Here is the CBO breakdown.

I did some investigating.

You can get the Table 2.1. Personal Income and Its Disposition data from the National Income and Product Accounts (NIPA) database of the US Bureau of Economic Analysis.

The data breaks Personal Income down into sources including Compensation of employees, Proprietors’ income, Rental income, Personal income receipts on assets and Personal current transfer receipts (which include Government social benefits to persons; Old-age, survivors, disability, and health insurance benefits; Government unemployment insurance benefits; Veterans benefits; and Family assistance).

What proportion of the Personal current transfer income is cyclical is not published. So you have to make assumptions.

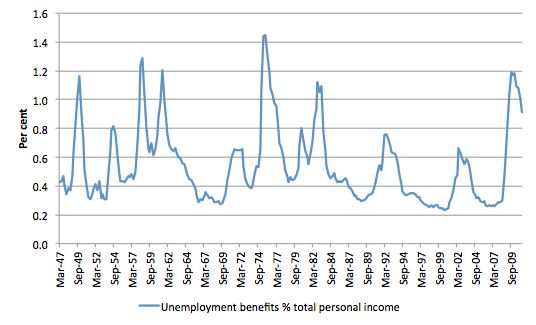

The average unemployment benefit payments as a proportion of total personal income has been about 0.5 per cent. From 1947 to 2008, the average was about 0.52 per cent.

At the worst part of the recent recession (September 2009 quarter), the ratio rose to 1.2 per cent – which in the scheme of history is a huge jump. By March 2011, the ratio had fallen to 0.9 per cent.

In billions of US dollars, in March 2010 the outlays on unemployment benefits was $US146 billion (the peak). The pre-crisis outlays were around $US30 billion. So the difference which is entirely down to the crisis represented about 3.2 per cent of total outlays and if that was not spent and GDP was at its trend rate (between 2000 and 2008) the outlays as a per cent of GDP would be closer to 23 per cent rather than the actual value of 25.3 per cent. So that is 2.2 per cent of GDP just in unemployment benefits payments.

The arithmetic is rough and constrained by time but I think it is fairly accurate reflection of the cyclical impact arising from the increased payments of unemployment benefits.

The following graph shows the evolution of that ratio since March quarter 1947. Once again it shows you how exceptional the current period is in terms of severity of downturn.

The NYT article understands what the impact of fiscal austerity will be. It notes in terms of the income loss that will follow the impending termination of unemployment benefits for many in the US that:

Unless hiring picks up sharply to compensate, economists fear that the lost income will further crimp consumer spending and act as a drag on a recovery that is still quite fragile. Among the other supports that are slipping away are federal aid to the states, the Federal Reserve’s program to pump money into the economy and the payroll tax cut, scheduled to expire at the end of the year.

Spending equals income. Either the non-government sector can increases its spending to reduce unemployment (and the budget deficit) or the government sector has to. There are only two sectors.

All the signals are that the private sector is bunkering down and the economy will weaken further once the public spending support also wanes. The fact that the so-called leadership of the US Congress meet with the US President to plot massive spending cuts amounts to deliberate sabotage of the welfare of their own citizens.

I thought some of the statistics the NYT article presented should be headlines.

1. “In Arizona, where there are 10 job seekers for every opening, 45,000 people could lose benefits by the end of the year … Yet employers in the state have added just 4,000 jobs over the last 12 months”.

2. “In Florida, where nearly 476,000 people are collecting unemployment benefits, employers have added only 11,200 jobs in the last year.”

etc

The other interesting aspect of the article was the reporting of research from the US Department of Labor which:

… estimated that every $1 paid in jobless benefits generated as much as $2 in the economy.

I have a lot of time for the economist who did the research (Wayne Vroman). He has done some excellent applied studies relating to cyclical upgrading effects etc (Okun-type studies) over the years. I doubt he is an MMT proponent but his applied labour studies are sound.

But plug that result – a spending multiplier of 2 – into the “fiscal contraction expansion” mantra that the deficit terrorists want us to believe in. The reality in Ireland, Britain, Greece and the US already is clearly showing us that the expenditure multipliers are well above 1. The mainstream economists try to tell us they are very low if not negative (crowding out).

Conclusion

I might do some more refined analysis of the CBO estimates when I get a clear span of time. There estimates of the cyclical component of the US federal budget are too low but even then they are scary enough (very large).

Once again – a nation is being brought to grief by its failed leadership and the financial press mostly reinforce the lies.

I think I will have to stop looking at the US for a while – it is downright depressing.

That is enough for today!

Bill,

Tell me if i’m wrong but did I just sum up the heart of MMT into the Austin’s Law of Monetary Optimization (for lack of a better name ;-0 )

“Monetary optimization at any level of public spending requires balancing tax revenues with spending while running deficits at a rate corresponding to users saving rate.”

The US government as a currency issuer should never seek to balance the budget, but rather optimize it for a desired output level within the real constraints, such as production capacity, of the marketplace.

For an explanation visit link below:

http://dollarmonopoly.blogspot.com/2011/07/austins-law-of-monetary-optimization.html

Have no idea if it’s valid nor not. Care to comment?

Great article, but I think I may have spotted a typo –

“Outlays as a proportion of GDP returns to 20.397505 per cent using real GDP growth and 20.5356493 per cent using the CBO real GDP gap measure. In other words, most, if not all of the decline in tax revenue at present is cyclical.”

Shouldn’t the above read “…most, if not all, of the increase in outlays at present is cyclical”?

Bill,

have a look at this:

http://www.ecb.int/pub/pdf/scpwps/ecbwp1361.pdf

ECB paper stating that austerity can lead to growth if expectations are for austerity to follow.

Another way of looking at taxes is to use them as an incentive to make investment/jobs. In other words if profits are not being used for investment they should be removed by the government. This will make investment more inviting than profits and will increasing spending. As Bill has said “if you don’t like deficits, then you should invest”. It is time to take out the stick and forget about the carrots for a while to get corps to invest their money instead of buying T bills and other forms of guaranteed return.

Does MMT have any similar ideas?

Sorry to drag you back into the swamp pit called the US government, but since you liked Bloomberg’s graph so much, I though you might be interested in a new report by Paul Ryan’s Budget Committee with some nice “down the rabbit hole” graphs by Stanford “economist” John Taylor. (Got some causality confusion there, John?) In fact, except for the part where some recent work by Alan Greenspan is brought in, you might think that Ryan had a crush on Taylor if you just counted the number of times his name appears in the report. Fortunately, it’s a pretty short report, which I guess means that even the Republicans are starting to run out of garbage to peddle. Unfortunately, Barach Obama is becoming indistinguishable from Paul Ryan.

Dear Lewis MacKenzie (at 2011/07/13 at 2:37)

Thanks very much. It was a typo. Now fixed.

best wishes

bill

Craig, Your attempt to summarise MMT in one sentence isn’t bad, but I’d suggest some improvements as follows.

First, your sentence above starts “Monetary optimisation…”. In contrast, the version on the site of yours linked to above starts “Fiscal optimisation…”. So which is it? I suggest the distinction is irrelevant because the fundamental aim is to adjust private sector net financial assets (money or bonds) in such a way that the private sector is induced to spend at a rate that brings full employment. Whether those assets are boosted by cutting taxes (which would be “fiscal”) or by for example a helicopter drop, which would be monetary, doesn’t matter.

Next, I’m not keen on the phrase “balancing tax revenues with spending while running deficits”. If tax and revenues are balanced, there isn’t a deficit, is there?

So here’s my attempt at a one sentence summary of MMT: “Government should try to adjust private sector net financial assets (money and bonds in particular) so as to induce the private sector to spend at a rate which brings full employment.”

“Whether those assets are boosted by cutting taxes (which would be “fiscal”) or by for example a helicopter drop, which would be monetary, doesn’t matter.”

“Helicopter Drops Are FISCAL Operations”

http://neweconomicperspectives.blogspot.com/2010/01/helicopter-drops-are-fiscal-operations.html

“Does MMT have any similar ideas?”

I’m not sure the MMT economists have done the work in depth to understand whether hoarding has any economic effect in the long run. Certainly concentrations of wealth appear to alter political direction so arguably there is a systemic issue there where the economics negatively affects the politics.

Remember that MMT is a description of the way the monetary system is and how it works in reality. You can use it for any political ends and in any political framework.

So if the politics favours hoarding by a vast number of people then knowledge of the Modern Money system allows you to make it generate even more for you to hoard.

@Ralph Thanks. Tom was steering me towards fiscal optimization in our exchange here which I started to agree with but now to your point the distinction seems irrelevant. What to call it may be best decided by what it conjures up in people’s head – in other words does it help or hurt “sell” the idea.

@”I’m not keen on the phrase “balancing tax revenues with spending while running deficits”

I agree. What about this: “Fiscal optimization at any level of public spending requires offsetting tax revenues with spending while balancing deficits at a rate corresponding to users saving rate.”

Keep in mind. I am specifically trying to keep my laymen explanation in a “binary” form. Does this sound better?

@Max Thanks. Will review. Warren gave me input on several of these lines and the one I like that I really liked that speaks to “Helicopter Drops Are FISCAL Operations” is this concise little puppy:

The issuer needs to replenish the supply of currency by either spending and/or adjusting taxes depending on one’s politics.

Craig,

I’ve lost that line half way through. It isn’t simple enough to get across what is a counter-intuitive notion.

Fiscal optimisation is an economic shock absorber. It dampens extremes. If the non-government sector spends to little, the government has to spend instead If the non-government sector spends too much, the government has to take money off them.

@Neil Yes , my comment was a bit out of context. So what I’m trying to do is apply a theory of constraints to fiscal policy. I am about to update my entire site but this what I’m working on:

The nature of government debt as a digital resource and the impact of users choosing to save informs the currency issuer’s of it’s options within the system as the monopoly producer, lender, and price setter of money. For any given level of output, it’s the currency issuer’s responsibility to maintain general price stability when currency users choose to save. In order to so, the issuer needs to replenish the supply of currency by either spending and/or adjusting taxes depending on one’s politics. Likewise, if users are not saving, then the issuer needs to spend less or tax more. Fiscal optimization for any desired output level maintains overall price stability by offsetting public spending with taxes while balancing monetary operations by running deficits at currency users’ savings rate.

BTW – “digital resource” is mentioned earlier in the paper:

All monetary operations by the issuer are derived in government liabilities. All liabilities by the issuer create a corresponding asset for the currency user as a matter of accounting. The issuer’s debt is a digital resource – a digital account corresponding to all the savings of currency users’ in banknotes, deposits, and treasuries.

Neil Certainly concentrations of wealth appear to alter political direction so arguably there is a systemic issue there where the economics negatively affects the politics.

Money gets concentrated at the top through economic rent. Concentration of money = political power. Distribute political power by taxing away economic rent, otherwise lose democracy. (This is pretty much a summary of Michael Hudson’s work.)