The other day I was asked whether I was happy that the US President was…

I'll buy the Acropolis

Sell, Sell, Sell – which referred to renewed calls for an even more expansive privatisation program in Greece than is already under way. The initial program of asset sales was projected to net more than 20 per cent of GDP in funds. But now the EU bosses want more. There appears to a group denial in Europe at present which is being reinforced by the IMF and the OECD and other organisations. They seem to be incapable of articulating the reality that if you savagely cut government spending while private spending is going backwards and the external sector is not picking up the tab then the economy will tank. Under those conditions policies that aim to cut the budget deficit will ultimately fail. But in the meantime the reason we manage economies – to improve the real lives of people – are undermined and living standards plummet and the distribution of income and wealth move firmly in favour of the rich. But if the price is right I’ll buy the Acropolis (and give it back to the people)! The German press have been baying under the moon for the Greeks to sell islands and even the Acropolis. But now this mantra is standard IMF/Europe Finance minister’s talk. The Euro bosses are telling Greece that it will only bail them out further if they sell more public assets and impose harsher “structural” reforms. After the emergency meeting in Luxembourg recently, the Prime Minister of that nation was quoted as saying:

Urgent measures are needed in Greece in order to reach its fiscal targets … [including an] … increase the volume of privatisation ..The normally liberal Dutch were garnering support for:

… more radical measure: creating an external agency run by the EU to take charge of selling the assets.Haven’t they ever heard of democracy? Even the Economist notes that this would constitute “an erosion of sovereignty that is likely to run into fierce resistance, and not just from Greece”. All of this is to avoid having to “reprofile”, “reschedule” or debt default. All these buzz words are being bandied around at the moment. My estimate is that the Greek government will not be able to repay its current debt load given the state of its economy and its loss of currency sovereignty (which effectively makes these debt – foreign-currency denominated). Meanwhile, the IMF has had a team in Greece recently and their conclusion is that the Greek government has to “speed up reforms”. In this Sydney Morning Herald article (May 18, 2011) – IMF warns Greece over sluggish reforms – a senior IMF official (one that is not in prison) was quoted as saying:

The programme will not remain on track without a determined reinvigoration of structural reforms … Privatisations make a real difference … there would be a very substantial change in debt sustainability.Privatisations typically fail especially if they involve assets that yield revenue to the government. Mainstream economists claim the price will be driven by competition to reflect the discounted lifetime income flow from the asset. They are usually wrong about that. The price offered is almost always discounted to ensure the politicians are not embarrassed by a “non-sale”. So the private sector effectively steals the assets and the government loses the revenue stream. The point is that a budget deficit is an accounting result of flows of spending and revenue. Those flow occur day-in day-out. Selling an asset is selling a stock and the pay down of debt is a once-off event. The SMH article also reports that the Greek people are now resisting their government’s attempt to demolish their economy which is frustrating the IMF. It is always a nuisance for the Washington-based, non-elected organisation when a bit of democracy gets in the way. While on the IMF, here is a snippet from a Press Conference that the IMF Director of External Relations Department gave on May 12, 2011. She was asked whether the IMF adjustment demands for Greece were too severe and replied:

MS. ATKINSON: The program when we designed it was designed so as to address the financing problems that Greece had and obviously we and others can provide a certain amount of financing, but to make the books balance you also need to have adjustment and that’s the judgment incorporated in the program.The question that the journalists should have then asked was: Why should Greece run a budget balance? I went back through my records (notes, text archives etc that I have built up over the years) to see what I knew about Atkinson. Prior to joining the IMF, Atkinson wrote an article in the Financial Times (May 17, 2002) – Forget Sovereign Bankruptcy Plans – which you might be excused for thinking was her application letter for her job at the Fund. In that article you read:

Question: when is a country not like a company? When it has run out of money. A company can declare bankruptcy. A country cannot. Debt work-outs for companies are guided by domestic bankruptcy laws. Debt work-outs for countries are not. They can be long and messy.Correct answer: A country is never like a company because regardless of any (imprudent) voluntary arrangements the government has entered into – such as pegging its currency, borrowing in foreign currency, dollarising, euro-ising (I just invented that term), the nation can withdraw from those arrangements – by floating, restructuring loans in domestic currency, reintroducing its own currency etc. A company that goes broke does not have that option. A nation can never be bankrupt in its own currency despite the IMF working hard over the years to blur and obfuscate that fact. It never faces a solvency issue in its own currency. So even before she joined the IMF, Atkinson was spreading lies about the essential nature of monetary systems as they pertain to governments. In that same article she made the following extraordinary statement:

When crisis hits, it is hard to tell whether policy reform and temporary official financing will be enough to restore investor confidence. In a few cases, debts may have to be restructured. Tough judgments are involved in deciding when restructuring is the only option and how to share the pain between debtor countries and their creditors. The IMF is the only body with political legitimacy and the technical ability to make such judgments.Which brings me to this interesting article in the Financial Times (May 18, 2011) – Fund must turn away from DSK’s economic mistakes which was written by a fellow at the right-wing American Enterprise Institute. The article says that unlike those who have praised Dominique Strauss-Kahn as a progressive who placed the IMF at the centre of the European recovery effort the reality is that:

History … is more likely to remember him as the man who put the IMF on the road to decline, by his misguided handling of the eurozone debt crisis.I rarely agree with a right-wing author but in this case – as they say in the classics – I couldn’t have written it better myself!. But the agreement is fleeting. Lachman (the author) says:

Mr Strauss-Kahn’s decision to treat the crisis as a matter of liquidity rather than solvency led the IMF to eschew any notion of debt restructuring, or exiting from the euro, as a solution to the periphery’s public sector and external imbalance problems. Rather, he opted for draconian fiscal tightening and radical structural reform as a cure-all for Greece, Ireland and Portugal. Experience with such policies in Argentina in 1999-2001 and in Latvia in 2008-09 should have informed the IMF that, under the euro – the most fixed of exchange rate systems – such a policy was bound to produce the deepest of economic recessions. The fund should also have anticipated that deep recessions would erode those countries’ tax bases and undermine their political willingness to stay the course of adjustment. The poor economic performance now evident in Greece and Ireland therefore risks blackening the IMF’s reputation in Europe in the same way as its programmes in Asia and Latin America rendered the fund a pariah in the 1990s. At the same time, economic programmes for Europe’s periphery that had little chance of restoring public debt sustainability have torn the IMF’s credibility in the financial markets.In that quote there is an underlying theme – about public debt sustainability – that I would not entertain. But the general point is sound – the IMF and OECD and other non-elected organisations tout prescriptions to national problems based on economic theories that are faulty. They typically never make forecast errors on the “pessimistic” side. So when they impose “conditions” on nations accepting funds, the IMF typically projects a more rapid recovery than a reasonable assessment of the situation would warrant. As an exercise, go back through the years and match the IMF forecasts for nations that they have under Standby arrangements or Extended Fund Facility (or similar programs relevant to the historical period) with the reality. The “conditions” they impose scorch the Earth and generally fail to achieve their stated goals – to improve living standards etc. They certainly redistribute a lot of national income from poor to rich. They certainly alter the wealth distribution in favour of those rich interests who buy discounted state assets. But the IMF don’t admit that or provide analysis of it. It is no surprise that the Greek deficit as a proportion of GDP is not falling. It is not because the government is being slack in implementing the structural adjustment program. Perhaps it is slack but that misses the point. When you cause real economic growth to contract sharply and sustain that contraction over several years the automatic stabilisers will guarantee a budget deficit. I also agree with Lachman that Greece is effectively “insolvent” under present arrangements. It has debt that it is struggling to service denominated in a “foreign-currency” (the Euro) and the private bond markets which it depends on because it entered the EMU and gave up its sovereignty are not particularly willing to go on lending to it. In the IMF’s Third Review Under the Stand-By Arrangement (the bailout) which they published in March 2011, we read:

The authorities remain focused on putting in place a critical mass of structural reforms to support an investment and export led recovery … Overcoming Greece’s legacy of weak market contestability and high administrative burdens necessitates a broad and deep agenda, unprecedented in Europe, covering far reaching labor market reform, product and service market liberalization, and reforms to encourage entrepreneurship.It is clear that the hoped for export-led recovery and private investment boom has not materialised. It was an ideological hope that it would. The conditions that the Greek economy faces – especially with other nations also pursuing austerity – makes it near impossible that the external sector would grow fast enough in conjunction with private investment to replace the plunge in consumption. The IMF know that. In the same Review they admit that in the last year Greek “household consumption faltered” – “Building permits have continued to decline” – “Industrial production is still declining” – “economic sentiment remains poor” and despite unit labour costs falling (wage costs falling faster than a dramatically declining productivity) – “Greece has continued to lose world export market share”. Moreover, the IMF concludes that “Household credit growth has turned negative…” and “corporate credit growth continues to slow”. Please read my blog – Fiscal austerity – the newest fallacy of composition – for more discussion on this point. I agree with Lachman that “one year after the European Union and IMF’s $150bn loan package, the Greek adjustment programme is not working”. I also agree that:

At the heart of the IMF’s failures to date in Greece was the prescription of a policy approach that had little chance of success within the constraints of a fixed exchange rate system that precludes devaluation as a means to promote export growth, which is an offset to radical fiscal policy tightening.Even with a flexible exchange rate, the Greek economy would not be able to withstand the extent of discretionary fiscal tightening that is going on. But in saying that, a flexible exchange rate would have been beneficial. But then if you are going to advocate a flexible exchange rate you are endorsing an exit from the EMU which then changes the way we think of Greece altogether. Then the so-called “government funding problems” evaporate into thin air. Governments can rearrange the never-ending increase in the prices. The Greek government could ignore the ECB and the private bond markets and introduce public employment programs immediately. The adjustments involved in re-introducing their own currency would be tough and there would be an inflation risk but my assessment (as the gratuitous outsider) is that the net costs involved in the next five years would be less than what they will have to endure by staying in the EMU. Either way, they will have to default on the debt. But in my assessment it is much better to do that Argentina-style – by restoring your own currency sovereignty. Lachman is also correct when he says:

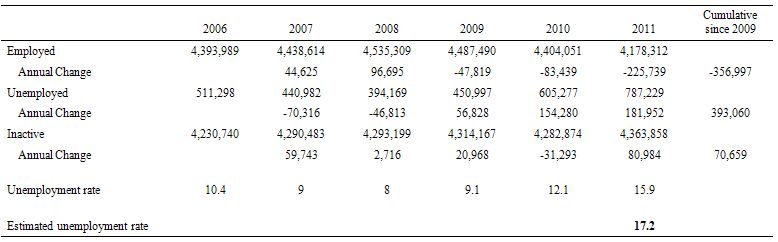

However, what is difficult to understand is why, with the poor economic performance of Greece, the IMF chose to repeat the same conceptual policy mistake in its adjustment programme for Ireland in November 2010 and in its proposed programme for Portugal right now. What is even more difficult to understand is why the IMF is now also proposing that Greece should apply more of the same policy prescriptions that have brought its economy to its current parlous state.To put the preceding discussion into perspective, I updated some of my databases today. The following table used data from that publication and shows the main Labour Force aggregates as at February in each year (2006-2011). I computed the cumulative change since the crisis really started to impact (2009-11). You can see that the economy has lost (net) 356,997 jobs which as a percentage of current employment (February 2011) is around 8.5 per cent. 393,060 extra people are officially unemployed. Note the inactivity changes. These could be demographic in nature but are likely – especially in 2010 and 11 – be motivated by cyclical events. If we assume that the 80,984 who left the official Labour Force between February 2010 and February 2011 were discouraged workers – that is, people who would prefer to work but had given up looking and therefore failed the activity (search) tests built into the Labour Force survey instrument – and add them back into the Labour Force as “unemployed” then the unemployment rate would be 17.2 per cent in February 2011 rather than 15.9. Either way it is intolerable that an advanced nation would tolerate an official unemployment rate of 15.9 per cent and be endorsing and introducing policies that will make that rate climb even higher and stay high for some years,

The most recent Labour Force data (published May 12, 2011) for February 2011 shows that the:

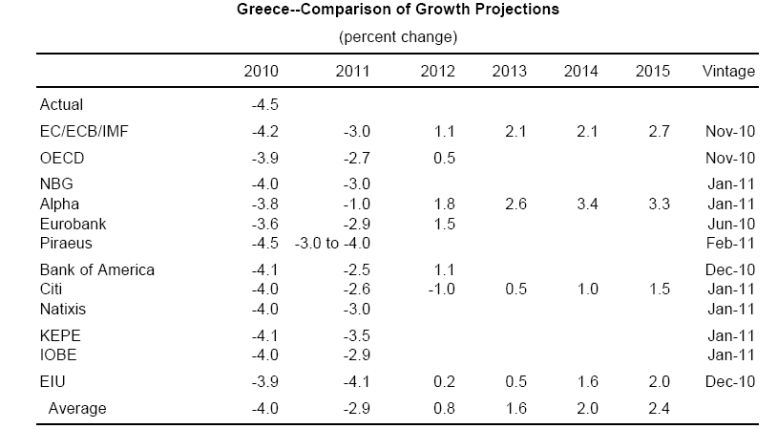

The most recent Labour Force data (published May 12, 2011) for February 2011 shows that the:

Unemployment rate in February 2011 was 15.9% compared to 12.1% in February 2010 and 15.1% in January 2011.Official Greek data is available from the Official Hellenic Statistical Authority (EL.STAT). If we think back to the June 2010 OECD Employment Outlook, at a time when that organisation was berating the Greeks and demanding ever tightening fiscal policy, the OECD forecast that the unemployment rate in Greece would rise to 12.1 per cent in 2010 and 14.3 per cent in 2011. So their projections were short of the mark by a very large 2 per cent in 2010 and 2011 will prove them to be even less accurate. The OECD also projected (in June 2010) that employment would “ease” by 2.8 per cent in 2010 when the Table shows that it plunged by 5.1 per cent in the period February 2010 to 2011. Given these forecasts are used by these agencies to frame their positions and influence the policy debate you would think their opinions would be ignored after getting it so wrong so often. One question I have: why does the Greek Statistical Authority take so long (3 months) to publish their monthly Labour Force Survey data? A quarter lag is often the case for National Accounts data because it is more complex but the Labour Force data should be available within a few weeks of the survey instrument being executed. You might also consult the IMF’s Third Review Under the Stand-By Arrangement (the bailout) which they published in March 2011. The following table (is taken from their page 9 Table) and reports the various real GDP growth forecasts for Greece. All but Piraeus (a Greek Banking Group) understated the extent to which the Greek economy went backwards in 2010. Note that all are more optimistic than Piraeus in 2011.

The National Accounts flash estimates (provisional estimates) for the first quarter 2011 which were released on May 13, 2011 show that real GDP fell by 7.7 per cent over the last year.

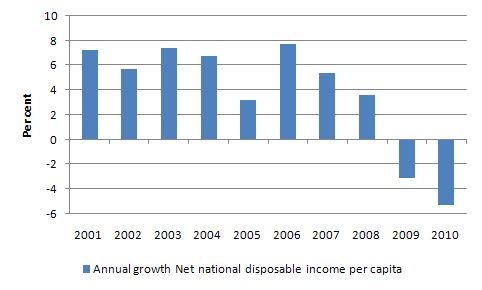

What all this means is that living standards continue to fall in Greece. The following graph shows the Annual Growth in Per capita Net National Disposable Income for Greece from 2001 to 2010. In 2009 it plunged 3.1 per cent and in 2010 it fell a further 5.3 per cent. The estimates available for the first quarter 2011 indicate that it will continue plunging. The real figures would be similar in direction given the inflation rate is low and stable.

The National Accounts flash estimates (provisional estimates) for the first quarter 2011 which were released on May 13, 2011 show that real GDP fell by 7.7 per cent over the last year.

What all this means is that living standards continue to fall in Greece. The following graph shows the Annual Growth in Per capita Net National Disposable Income for Greece from 2001 to 2010. In 2009 it plunged 3.1 per cent and in 2010 it fell a further 5.3 per cent. The estimates available for the first quarter 2011 indicate that it will continue plunging. The real figures would be similar in direction given the inflation rate is low and stable.

And on that note I read the the ABC News headline today (May 19, 2011) – Embattled IMF chief resigns. That was good news for the afternoon.

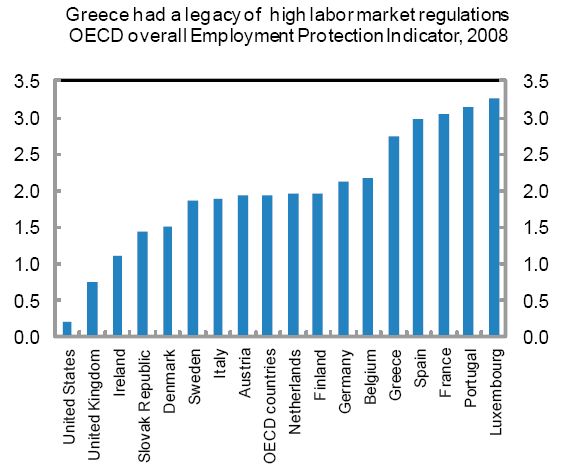

And in closing, the IMF’s March 2011 Review had this graph (page 36) which carried the title “Greece had a legacy of high labor market regulations – OECD overall Employment Protection Indicator, 2008”.

And on that note I read the the ABC News headline today (May 19, 2011) – Embattled IMF chief resigns. That was good news for the afternoon.

And in closing, the IMF’s March 2011 Review had this graph (page 36) which carried the title “Greece had a legacy of high labor market regulations – OECD overall Employment Protection Indicator, 2008”.

Note the status of Luxembourg and reflect back on the statements made by the Prime Minister of that nation after the emergency meeting in Brussels the week before last. Hypocrisy abounds.

Also note that the “least regulated” labour market (the US) has one of the worst unemployment rates at present.

Conclusion

Takis or Vassilis, please let me know when the Acropolis is up for sale.

That is enough for today!]]>

Note the status of Luxembourg and reflect back on the statements made by the Prime Minister of that nation after the emergency meeting in Brussels the week before last. Hypocrisy abounds.

Also note that the “least regulated” labour market (the US) has one of the worst unemployment rates at present.

Conclusion

Takis or Vassilis, please let me know when the Acropolis is up for sale.

That is enough for today!]]>

A fact should point out the double standard used dealing with the public debt of Greece. Germany owes Greece in war reparations and forced occupation loans with interest about 160 billion euros which has never repaid. Furthermore, in 1954 German debt was restructured with a 50% haircut and Greece was one of the CREDITORS that forgave this 50%! Notice that no conditionality was imposed and no austerity measures rather assistance for the German economy to grow! Now Germany repays this assistance with austerity demand upon Greece that brings severe poverty and unemployment to the Greek population in addition to fire sale of public property. Unfortunately, Greece has traitor politicians that accept this economic occupation! As I have argued before, the only way change can happen is when people revolt!

How about selling you George Papandreou and his government instead?

How about selling you George Papandreou and his government instead?

That’s a quick way of raising about 10 precious euros

Hello Bill.

In case you don’t know, there is a lot of talk going on already here about getting out of the euro

(NOT coming from the media of course…)

A recent international Conference on Debt and Austerity held in Athens (May 7-8) produced a declaration

(http://www.elegr.gr/details.php?id=134)

which as a first step proposes debt auditing, and “Sovereign and democratic responses to the debt crisis”.

Some of the people who signed it are here: http://elegr.gr/details.php?id=13

It seems also that similar moves are in progress in Ireland (see e.g http://www.debtireland.org) and apparently in Portugal.

The only realistic case for debt repudiation comes from the moral hazard issue of lenders pressuring for debt repayment knowing that such response will cause extreme hardship and threatens the livelihood of a debtor whether individual or nation! I have said that to members of this movement! The case of Greece is not like Equador! Furthermore, the time it takes to conduct such investigation is too long and the data are not always available. In any case, there is no problem for such work to proceed even for psychological reasons and pressure that it can impose on the lenders!

I agree with Panayotis. Living in Germany being from Austria I can only apologize to the Greek people. To listen to the discourse here about the European debt crisis is depressing and one feels ashamed to be a citizen of the now so called “core” EZ countries – the term “core” is in itself another insult to the other countries. That said I can hardly blame the normal people on the street for their delusions. The 24/7 media barrage with economic nonsense from 99% of Bill’s colleagues (must also be very depressing to have such “colleagues”) and our politicians is clearly responsible for all these public misconceptions.

Only one example for the German hypocrisy from today’s newspaper. In 2011 nominal wages in construction, chemistry and public service will rise by 2.0-2.6% which means real wages will decrease compared to 2010. Our politicians muse about competitiveness by internal devaluation in Greece, Ireland, Portugal, … and then counteract such efforts by further internal devaluation in Germany. If one looks at the development of labor unit costs in the EZ it is quite obvious who’s the European villain. Ironically the € was meant as the next step towards the real thing and now it destroys the European Union.

The tragedy of all of this is that the euro was supposed to be a way of cementing European integration. In reality it is fast becoming like Europe was in the lead up to WWII. One thing that I don’t think gets enough air-time is that Greece is very bad at taxing the richest Greek people. I’m not saying that that offers a full solution only that that would be preferable to privatizations.

Bill wrote “Why does the Greek Statistical Authority take so long (3 months) to publish their monthly Labour Force Survey data?”

Greece must have one of the worst public sectors in Western Europe as far as efficiency is concerned. This is more evident in the parts of the public sector where the work is mostly paperwork – which means, utilities are relatively more efficient than the rest. The Greek Statistical Authority is a particular disgrace. A real shame.

The above is a stone-cold real fact, as they say across the pond, and not some ideologically-driven statement. One of the reasons that Greece was “first in crisis” among Eurozone members is the wretched state of the Greek public sector, a state to which it’s been brought by chronic corruption, nepotism and partisan politicking. As citizens of this country, we carry our share of blame in full. (This does not mean that the status of the public sector is the cause of the crisis. The wretchedness of the public sector, though, both blinds Greeks as to the true cause of the crisis and provides our Euro-“partners” with a pretext to clobber us on the head repeatedly.)

Which is why, amidst the crisis, in poll after poll, the majority of Greeks agree “in general” with privatising “everything”!..

Seeing as a significant portion of the Greeks responding to these polls work in the broad public sector themselves, this is a clear sign of widespread hopelessness and desperation on the part of the citizenry with the political leadership. It’s the same reasoning through which Greeks in their majority agreed (per polls taken at the time) with having euros instead of drachmas was that they held no hope whatsoever of the political leadership fixing the chronic ills of the Greek state.

“What now, that the [foreigners] did not come? They were a kind of solution.”

Yep, let’s all move to Switzerland.

“loss of currency sovereignty (which effectively makes these debt – foreign-currency denominated).”

I would have said they converted stock of publicly issued financial assets into real debt. Im surprised Greece didn’t go bankrupt very first day they adopted euro – that would have been hilarious. 🙂

Vassilis,

1. You are blaming the Greek people and this shows you are a victim of foreign propaganda and the complex of inferiority many Greeks feel! Greeks are hard working people with many faults but also many good traits; they are hospitable, full of life and in their family lifes they are very responsible. They have far less debt than most Europeans, they own their homes and they are happy people.

2. The problem is not the public sector but the private sector entreprises/professionals that do not invest, they have “captured” public spending with waste and they tax escape and capital escape! The introduction of the euro helped this process since it made it easier to become importers rather than producers (less exchange rate risk, transfer pricing opportunities). The public sector is inefficient but this is only a reflection and no worse of the private sector. Is the public sector large? NO, by any European standard especially as it acts as an employer of last resort since the private sector is not investing and producing!

3. It is easy to fall into the trap of blaming the working people living on a salary and pension but they are not responsible for the mess! The public debt grew as the recession made things worse and the politicians were incompetent to provide a vision and use public investment to make up for the dismal state of private investment.

4. The worst problem was the foolish adoption of the euro which favors the economies with an export orientation which is also responsible with allowing prices to rise overnight by 30-50% due to currency value illusion, reducing any competitiveness the Greek economy had. This without counting the loss of monetary/fiscal policy independence especially for an economy that needs high levels of public investment regardless of cyclical fluctuations which can only be assured if policy is not revenue constrained!

Thanks for reminders about the inept/deviously corrupt policies of the IMF; on the other hand, that institution has facilitated the pilfering of natural and other resources of many countries around the world to benefit that institution’s original funders/designers. The irony is that when the IMF-designer countries (USA, UK, France, Germany, etc) encounter financial crises, they do not solicit advice from the IMF financial experts (and for sensible reasons as pointed out several years ago by Simon Johnson, MIT economist and former head of IMF).

It seems inevitable that the wealthy elite of all countries adopt a modified version of the behavior economists describe as ‘beggar thy neighbor’ in that they use every trick they can think of to avoid paying taxes in order to gain personal advantage/satisfaction. The obvious consequence of placing the major burden of subsidizing the organizational system on the middle- and lower-economic classes is to eventually kill the ‘goose that lays the golden eggs’ (degrade the society/culture). Over time, of course, this approach leads one to question the presumed cleverness of the opportunistic vulture-members of society. Is this consideration relevant to the apparently wide-spread resistance among the ‘economists-to-the-elite’ to adopt the ideas proposed by the advocates of MM-economics?

In other news, I converted my first Austerian today. The lightbulb popped on and he said, “I think I can work with this!”

Bill:

Is there a scenario where Greece could introduce a drachma 2.0 internally (for taxes and internal spending) and retain the Euro as a “trade dollar” (not accepting it for internal payment of taxes, perhaps for foreign entities with tax liabilities due Greece) for some unspecified period of time?

I am assuming that the Greece economy has excess capacity – certainly of labor (and good ocean views).

Greece could conduct foreign trade in either drachma 2.0 or Euros, certainly imports would probably be denominated in Euro.

A complete withdrawal from the Euro would be extremely difficult, not that this would be easy.

Perhaps a default on the Euro would be a short-term good thing for Greece (then Ireland, then Portugal, then …), although ideologically it would be spun as “see fiat currencies are inherently unstable”. Especially since the ECB would be intimately involved in any restructuring.

I don’t see any difference between a debt restructuring and a currency default. It makes more sense for a country to default on “foreign” debt, so Greece needs to make it’s current debt foreign.

I just don’t know how NFA would be recalculated/negotiated.

BTW, I see the point on Luxembourg. Isn’t the total size of Luxembourg’s labor market about 150,000?

I guess we will soon see the last stage of the Greek drama. Our ECB dictators just announced they’re ready to turn off the lights in Greece. I can only hope the Greeks have some plan B in some drawer at the Central Bank of Greece. From FT Alphaville:

PS: @pebird I also think a parallel national currency would be the better solution. By doing so Greece could possibly avoid a major bank run by its citizen. Nevertheless introducing it would still create a mess for some time.

@Stone “One thing that I don’t think gets enough air-time is that Greece is very bad at taxing the richest Greek people.”

Isn’t it a middle and upper class tradition in Greece to run two sets of books, with much payment going via the black market. This is the source of many of Greece’s problems.

But isn’t the problem that the initial euphoria of EU and MU membership – plenty of money for development of the outer countries, which could/should have been used to equalise the developed and less-developed economies – has been dissipated. All of the new roads are being used to import German goods, and the Germans don’t realise (yet) that impoverishing their customers is not good for their long term prospects.

@ Panayotis

“You are blaming the Greek people and this shows you are a victim of foreign propaganda and the complex of inferiority many Greeks feel!”

Pls spare me the talk about “foreign propaganda”. The Greek statistical service takes three months to put out data that should take a week. Bill Mitchell, who’s engaging in anything but “foreign propaganda”, wondered about that. And having been there myself too, I pointed out the severe backwardness of the Greek state’s functions. This much is evidenced, unfortunately, by studies conducted not by some “foreign agents” but by Greek “progressive” media.

“Greeks are hard working people with many faults but also many good traits; they are hospitable, full of life and in their family lifes they are very responsible.”

Suppose this is true for all Greeks. What does it have to do with anything?? We’re talking about the sorry situation the Greek state is in, something which unfortunately amplifies the problems Greece is facing (after it abandoned its currency sovereignty) and provides the “Euro-bosses” with excuses to put the boot in.

“It is easy to fall into the trap of blaming the working people living on a salary and pension but they are not responsible for the mess!”

The working people and the pensioners of Greece are entirely innocent. I never claimed otherwise.

“The problem is not the public sector but the private sector entreprises/professionals that do not invest, they have “captured” public spending with waste and they tax escape and capital escape!”

The private sector in Greece may be faulted for a lot of things but the crisis was not of its making. Greece is the first Eurozone country to hit the brick wall simply because we have net-spent faster than the others, with a large CAD on top. Tax evaders indeed helped Greece reach the crisis faster – but they did not “cause” it. Portugal, Ireland, Spain (and, somewhere in there, la France) will soon be joining us.

“The introduction of the euro helped this process since it made it easier to become importers rather than producers (less exchange rate risk, transfer pricing opportunities).”

If that’s the case, why hasn’t every country in the Eurozone become “importers”?

“Is the public sector large? NO, by any European standard especially as it acts as an employer of last resort since the private sector is not investing and producing!”

The Greek public sector is extremely badly functioning and this sorry state of affairs amplifies the problems the country is facing. The Greek state is a very bad “employer”, let alone an “employer of last resort”. Trust me, I know very intimately what kind of work provider the state currently is. We need to fix that, and soon, although this, in itself, will not solve our problems.

Arguing that Greece has only one problem, the Euro, is wrong. Greece needs to get back to its own currency as soon as possible, yes.

But after it gets back the Drachma (or whatever), the hard work starts! The Greek state must invest wisely; invite private sector investments; engage the productive classes once again; etc. How on earth is this going to happen when the Greek state’s apparatus is in such a state? And when the political leaders are incompetent and corrupt?

Getting out of the Euro, Panagiotis, is the easy part of the solution. What happens afterward is the tough part…

See you around.

See you around? I do not think you are around Greece but a victim of the foreign propaganda and the complex of inferiority that many Greeks feel! You are only repeating the same story that the Greek government and the Greek industrialists are presenting! Even if you reread your own statements you will realize the problems start with the private sector and extend to the public sector that acts to promote the private interests with waste and tax/capital escape! Private investment? Where is it? The previous government reduced profit taxes down to 20% and invetsments were reduced and not raised! The mistake of leaving the drachma and any return to it does not come alone but as apart of a more comprehensive program that i have been discussing in my tv/internet program. The problems about being importers than producers is well shown by the statistical data since the adoption of the euro! Why not in other countries? But it happened in various degrees in all peripheral economies of Europe and in Greece was more exactly because of the poor shape of the greek entrepreneureship! I did say if you have read what I said that the Public sector in Greece is inefficient but the fact remains that it is not larger than in other European economies and that it has acted as an employer of last resort since the private sector was not producing enough jobs! anybody who knows the Greek reality understand that if not ask the politicians about voter requeats for getting a state job.

Apart from repeating the same nonsense of the IMF/ECB/EU/greek Government which leads to the austerity program you have said nothing else. It is the greek people that are being asked to face the consequences of a failed private sector that profits from state waste and corruption lacks innovative skills, avoids investment and tax/capital escapes! Debt restructuring alone is not enough unless the private sector model is fixed and the public sector modernized and freed from the “capture” by private interests and banking sector! Have a nice day και αλλαξε μυαλα!

@Vassilis Serafimakis

“If that’s the case, why hasn’t every country in the Eurozone become “importers”?”

Perhaps, because the highly productive (euros per hour) “exporters” have been happy – till now – to send real wealth in exchange for the euros the less productive “importers” were given access to…

The worst thing a currency union makes to a relatively lower productivity country in the union is not that it blocks devaluation and hence limits exporting capability. It is that it blocks devaluation and hence everyday feedback for the country’s people to sense how much imports really cost in working hours.

The parallel here, surely, is between Greece/Germany and NE England/London. National economic policy in the UK has destroyed the economic base of the North East and, without any support from the national government, the region is unable to create a new one without massive investment in education and new industries. It also cannot devalue it’s way out of the problem. In the meantime, the region becomes a wasteland and probably is still exporting capital to the South.

Inside the Eurozone, the problem is also political as well as that of will. How do you persuade German voters to invest in the future of Greece?

But then it’s the same question in the UK. How do you persuade the voters of the South to invest in the North East? With our current neo-liberal masters, it ain’t gonna happen.

@Panayotis

What I wrote does not remotely imply what you’re “accusing” me of. I can only, therefore, suggest you re-read it but a bit more carefully. Otherwise, we’d be going around in circles. In any case, I do not think there’s much else to be said – apart from my assurance that, yes, I’m living in Greece!

And I quite like it living here.

Cheers. (And yassou.)

Let me explain a few things.

1. The public sector is expressed by a state apparatus whose function is to produce common goods and public services and whose performance is guided by civic duty for public purpose. This state structure can be inefficient as is in Greece although no more than the private sector as expressed by private firms and professionals whose function is to produce private goods/services and whose performance is guided by shelfish interest for private gain.

2. The private sector arrangements of firms/professionals is inefficient, not investing/innovating, importind instead of producing and it seeks to exploit priveledges extracted from the state apparatus. This is accomplished by “capture” of the state apparatus with comparative power exhibited as corruption waste in the form of overpricing and oversupplying private goods to the public sector. Furthermore, they utilize their comparative advantage in avoiding/evading practices to tax/capital escape and enforce negative externalities upon the economy exhbited together with inefficiency as structural deficits. Part of this privitization process of ther public sector is for politicians/public functionaries to perform exploiting their comparative power by capturing regulation and follow their shelfish interest instead of practicing thei civic duty for public purpose. They seek bribes as rents from other private interests that gain from deregulation of their activities that cause externalities and from regulation capture that cause waste as explained above.

The public sector is supposed to be inefficient. It’s job is to be effective in maintain demand and public service, not optimise capital.

And there is a reason for that. If the public sector was highly efficient, how could the private sector hope to improve things given their profit requirement and considerably higher cost of capital.

“NE England/London”

Not just NE England. It’s the South East of England vs the rest of the UK.

@gastro george

The problem in Europe is purely political. The project of European unification was born with the best possible intentions – peace across the continent. I would argue that the architects of the Union knew very well that setting as the first objective a political union would be an exercise in futility (what kind of good Englishman would accept foreign policy decisions taken in Paris?) so they attempted to force the political union as something ripe and inevitable after an economic union.

But, again, instead of promoting a correct economic union, which would mean a unique and common fiscal policy, they started with monetary unification. Having a pan-European fiscal policy would mean, again, having essentialy a political union. A common fiscal policy is by default all-encompassing, without regard for the ethnic attributes (in the case of Europe, national) of every region. Greece (or Ireland, etc) would be viewed and handled as Yorkshire is now treated and handled by London.

So, once more, what we actually did is put cart before horse. And we ended up with something like Madagascar, Paraguay and Nepal adopting a common currency.

I’m saying that the stakes in the viability of the Euro are not only the interests of the private and central bankers. The banking interests coincide with the objectives of those well-meaning Europeans who do not want to see the project of a united and consequently peaceful Europe fail. They see the failure of the Euro-currency as failure of the whole European Union project. We must disabuse ourselves and everyone else of this. The end of the Euro does not and should not mean the end of a (somehow) unified and peaceful Europe.

This is why we need, at this point in time, exceptionally bold and exceptionally far-seeing political leaders on both the national and the EU level. It’s not that we have too few like that, in my opinion; it’s that we seem to have none of the kind!

@Panayotis

1. Suppose I’m right and the Greek state sector is indeed rather badly organised and managed, in general. Even if true,

this is NOT be the cause of the current crisis!

2. suppose you’re right and the Greek private sector is infested with parasitic, tax-evading, state-funds-sucking entities (welcome to the private secotr!). Even if true, this is NOT the cause of the current crisis!

The cause of the curent crisis is NOT the state employees who take three months to produce something that should take them one week (as prof. Mitchell wrote); it is NOT the private corporation “sucking the blood of the workers”, pausing investments or evading taxation; it is not the working hours of the Greeks (the German tabloid press and Ms Merkel think we have too much sunshine and take too many vacations – that’s just eifersucht on their part); it is NOT the Ottoman empire; it is NOT any of the reasons promoted by the Greek or the European media

It is the fact that a decade or so ago, we surrendered our currency sovereignty and entered the Eurozone. End of story.

P.S. The United Kingdom has, until the Conservative Party’s win last year,avoided the Euro-crisis because, for all the wrong reasons (i.e. chauvinism and “Euro-scepticism”) kept the Queen’s currency and, once again in her history, stayed apart from the “continent”.

Life works in mysterious ways.

Neil Wilson says:

“The public sector is supposed to be inefficient.”

But only up to a point.

You obviously did not read my comment at (0:35) because you had noticed paragraph 4!

In order to understand the problem I suggest you read carefully all my comments rather than isolating parts for your own purposes! Enough for today! Next Thursday in my lecture program I wiil explain how the budget problem can be handled as I have dealt the drachma issue last Thursday and restructuring issues in previous segments. Of course my theoretical work deals with these issues analytically with logic and math presentations!

Panayotis, if you prove “with logic and math”, as you promise, that the root cause of the Greek economic crisis is not the surrendering of our fiscal sovereignty but “the poor shape of the greek entrepreneureship” or the private sector “not producing enough jobs” – then I will gladly print and eat prof. Mitchell’s latest article, without ladolemono.

I suggest you are confusing Factors with Causes.

My corner claims that when the private sector for whatever reason is saving (or tax-evading!) rather than investing, and performing poorly in terms of “entrepreneurship” (start ups, hirings, etc), the state has to move in. But, without our own national currency, our Greek state is helpless to do anything – except collect taxes! If we still had the Drachma, we might perhaps still be in some crisis or other – but the state would not be helpless in terms of fiscal policy.

I’ll demonstrate what I’m saying by a simple question: If Greece had private and state sectors similar (in whatever measure you choose) to Ireland’s, Spain’s or Italy’s, would we still be, inherently, in trouble or not?

Awaiting your proofs, I’ll prepare dinner.