I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Here are some answers, Greg

In his article – If You Have the Answers, Tell Me – he lists three uncertainties: 1. How long will it take for the economy’s wounds to heal? 2. How long will inflation expectations remain anchored? 3. How long will the bond market trust the United States? I suppose after 25 years of writing within the New Keynesian mould where most of the workings of the monetary system are essentially abstracted from (denied) and teaching students in your textbook that the central bank controls the money supply and budget deficits are inflationary that you might be a little confused about what is going on at present. If you then take into account that Mankiw and his ilk preached that the problem of the business cycle was largely solved by inflation targetting monetary policy and passive fiscal policy, I guess the crisis and its aftermath would be confounding. The “Great Moderation” is a term used by mainstream economists to describe the fact that both GDP growth and inflation were less volatile in the period from the mid-1980s to the onset of the financial crisis. They concluded that the “business cycle was dead” and that the main focus on policy should shift away from trying to manage aggregate demand so that economies provided enough jobs (why: because the self-regulating market would take care of that) and concentrate on freeing up markets and providing incentives for enterprise. This notion was called the “Great Moderation”. The problem is that the Great Moderation was in fact a delusional period where central bankers were elevated to the level of gods and economists intensified their lobbying for financial and labour market deregulation. The mainstream macroeconomists increasingly tried to claim in the 1990s and up until the recent crisis that they had “won” – been vindicated and those misguided Keynesian policies would never see the light of day again. The arrogance and short-sightedness of this viewpoint is exemplified in the 2003 presidential address to the American Economic Association by Robert E. Lucas, Jnr of the University of Chicago:

My thesis in this lecture is that macroeconomics in this original sense has succeeded: Its central problem of depression-prevention has been solved, for all practical purposes, and has in fact been solved for many decades. There remain important gains in welfare from better fiscal policies, but I argue that these are gains from providing people with better incentives to work and to save, not from better fine tuning of spending flows. Taking U.S. performance over the past 50 years as a benchmark, the potential for welfare gains from better long-run, supply side policies exceeds by far the potential from further improvements in short-run demand management.The Great Moderation became the norm in mainstream economics and further distracted them from seing what was really going on in financial markets which ultimately manifested as the global financial crisis. Please read my blog – The Great Moderation myth – for more discussion on this point. Mainstream economists started to concentrate on increasingly banal and crazy research programs and Mankiw’s work in this period was no exception. His models were developed within the New Keynesian tradition which is in a line of models dominates teaching within universities but is mostly inapplicable to a fiat monetary system. It is a concoction of classical theory of value and prices, late C19th marginal theory and monetary theory, and more recent add-ons to the free market models of the classics – the New Keynesian “frictions”. Gold Standard reasoning (or the convertibility that followed) is deeply embedded in the framework. New Keynesian economics assumes a government budget constraint works as an ex ante financial constraint on governments analogous the textbook microeconomic consumer who faces a spending constraint dictated by known revenue and/or capacity to borrow. It then imposes on this fallacious construction a range of assumptions (read: assertions – assumptions can usually be empirically refuted) about the behaviour of individuals in the system and generally concludes, that even with frictions slowing up market adjustments, free market-like outcomes will prevail unless government distortions are imposed. That body of analysis and teaching is a disgrace and would not prepare anyone to answer the three questions posed above in any coherent way. Please read my blog – Mainstream macroeconomic fads – just a waste of time – for more discussion on this point. But the “Great Moderation” overlooked that asset prices were increasingly not sending satisfactory signals to entrepreneurs interested in investing in real productive capacity and thus distorted the use of investment funds towards speculative financial assets. Moreover, with aggregate policy now maintaining a buffer stock of unemployment to discipline the inflation process and fiscal policy behaving in a largely passive manner (to support the “inflation first” monetary policy ideology), economic growth became increasingly dependent on credit growth to drive mass consumption. This reliance was also driven by the fact that the push for deregulation suppressed real wages relative to productivity growth thus redistributing real national income towards profits. That dynamic both placed more real income in the hands of the financial sector to engage in its casino-antics and meant that consumers had to borrow to continue to maintain growth in spending. So while the economists were sitting around congratulating themselves while sipping chardonnay about how they had solved the problem of the business cycle, the build up of debt and the increasingly risky speculative behaviour was guaranteeing that the next crisis would be very significant – it was only a matter of time. Mankiw and his fellow mainstream economists were oblivious to these developments. However, they were central to the body of work that Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) was offering – even as far back as the mid-1990s. We were warning about the early build up of debt and the generation of fiscal surpluses. Please read my blog – The origins of the economic crisis – for more discussion on this point. What the “Great Moderation” left us with was a major financial collapse leading to a collapse in private spending and the recession that ensued. Along the way it created a huge private debt burden and increasing income inequality. So it is little wonder that Greg Mankiw is now admitting he hasn’t got much idea of what is happening at present. Here are some pointers to help him answer his questions. 1. How long will it take for the economy’s wounds to heal? Mankiw says that “(w)hen President Obama took office in 2009”:

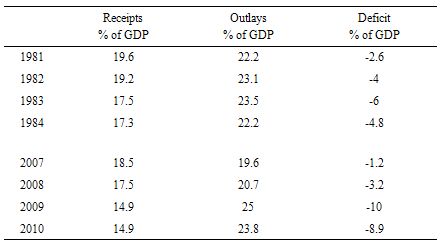

… his economic team projected a quick recovery from the recession the nation was experiencing.We can all agree that the “reality has turned out not nearly as rosy”. Growth is well below what was forecast which are now being downgraded not upgraded. Unemployment is now entrenched at high levels and will remain at those levels for years at the rate things are going. The US now has a long-term unemployment problem of the likes it has not seen before. It used to be said that one of the distinguishing features of the US relative to other advanced nations (particularly in Europe) is that the US never suffered lengthy periods of entrenched unemployment. Sure enough it experienced large swings in activity but the labour market recovered relatively quickly (compared to say Europe). Now the sclerosis that has haunted Europe for many decades (largely because of the conservative nature of economic policy there) is bedevilling the US. No surprise about that. Mankiw compares the recovery in the 1981-82 US recession with that of the current period and says that “there is no doubt that the pace of this recovery will come nowhere close to matching the one achieved” in the 1981 episode. The following Table is constructed from historical data available from the US Office of Management and Budget and shows the revenue and spending (and deficits) as a percentage of GDP for the periods: 1981-1984 and 2007-2010. The exact timing of the respective recessions is not perfect (given this is annual data) but it does give some impression of what happened. In the 1981-82 episode, the fiscal response was more significant (and the loss of revenue less severe). The scale of the more recent recession has been clearly more intense and the fiscal response required was larger than in 1982. That did not occur and goes a long way to explaining why the recovery is tepid and drawn out.

The fact is that the attempts by the mainstream economists to reassert themselves in the popular debate after being caught out completely by the ferocity of the downturn has led to renewed calls for fiscal conservatism and the imposition of pro-cyclical responses by governments. The politics has overtaken the economics and governments are now withdrawing fiscal support at a time when private spending remains fragile.

So the combination of a timorous fiscal response – which appears to have been just enough to ward off a Great Depression 2 outcome – and the premature fiscal withdrawal – are largely the reason why the recovery is weak and teetering.

Mankiw worries about the rise in long-term joblessness and the loss of job skills associated with that. He says:

The fact is that the attempts by the mainstream economists to reassert themselves in the popular debate after being caught out completely by the ferocity of the downturn has led to renewed calls for fiscal conservatism and the imposition of pro-cyclical responses by governments. The politics has overtaken the economics and governments are now withdrawing fiscal support at a time when private spending remains fragile.

So the combination of a timorous fiscal response – which appears to have been just enough to ward off a Great Depression 2 outcome – and the premature fiscal withdrawal – are largely the reason why the recovery is weak and teetering.

Mankiw worries about the rise in long-term joblessness and the loss of job skills associated with that. He says:

But because we are in uncharted waters, it is hard for anyone to be sure.The mainstream economists consider long-term unemployment to be a supply-side problem. As a consequence they have focussed labour market policy on training and full employability rather than creating enough jobs – the OECD Jobs Study approach which only emphasised the “supply-side” and overlooked the fact that tight fiscal and monetary policy were suppressing the demand side. The neo-liberal assertions were highly influential in the design of the 1994 OECD Job Study which influenced governments everywhere and led to the supply-side policy approach (and the abandonment of full employment). The principle claim was that long term unemployment possessed strong irreversibility properties. Irreversibility is sometimes referred to as hysteresis and suggests that the long term unemployed constitute a bottleneck to economic growth which can only be ameliorated through supply-side (rather than demand-side) policy initiatives. The research that has studied this issue has found no evidence that there had been any major structural shifts in the relationship between long-term unemployment and total unemployment. The sharp rises in long-term unemployment occurred as a consequence of drawn out recessions. All the dynamics of the long-term unemployment rate are demand-driven. They defy efforts to construct them as steady structural shifts driven by behavioural supply-side changes (say to welfare policy etc). History shows that when economic growth is strong enough employers access both pools of unemployed – short-term and long-term. This is contrary to the claim by mainstream economists who typically consider long term unemployment to be highly obdurate in relation to the business cycle and thus a primary constraint on a person’s chances of getting a job. Please read my blog – Long-term unemployment rising again – for more discussion on this point. So the answer to long-term unemployment is to provide enough jobs. Where skills are lacking the research evidence is also fairly clear – effective on-the-job training is best achieved within a paid-work environment – that is, on the job actually working. But for jobs to be created there has to be demand. That is the major problem in the US – insufficient public spending given the reluctance of the private sector to come to the party. 2. How long will inflation expectations remain anchored? The fear of inflation is a familiar theme of the mainstream literature and has underpinned its concentration on inflation-first monetary policy and the eschewing of activist fiscal policy (at least net spending initiatives that aim to support demand). It is clear that nominal contracts (which include prices) can be driven by inflationary expectations and that can be a self-fulfilling outcome. Mankiw says that:

Fed policy makers are keeping interest rates low, despite soaring commodity prices. Why? Inflation expectations are “well anchored,” we are told, so there is no continuing problem with inflation. Rising gasoline prices are just a transitory blip. They are probably right, but there is still reason to wonder.I personally think that strains on energy resources will drive the price of petrol up over the next several years – I outlined my views on the shifting composition of energy demand in this blog – Be careful what we wish for …. I think the days of cheap petrol and private transport are over for the advanced nations. I consider that a separate problem to controlling a demand-driven inflation. Central banks cannot really put a lid on imported inflation (via petrol prices) without severely damaging domestic activity. Inflationary expectations are probably more driven by the ability of the price setters to pass on perceived current or future cost pressures. With massive excess capacity in labour markets around the globe it is very difficult to mount a case that workers will be in a position to really prosecute wage demands sufficient to drive an inflationary spiral. So I am skeptical of the oil hikes being transitory – but if they are not major structural change will be required (moving away from oil-based production and transport). In the meantime I consider the lack of economic growth to be sufficient to quell the development of spiralling inflationary expectations. 3. How long will the bond market trust the United States? Posing this question really gives the game away. When hasn’t the “bond market” trusted the US? Mankiw says that it is a:

… remarkable feature of current financial markets is their willingness to lend to the federal government on favorable terms, despite a huge budget deficit, a fiscal trajectory that everyone knows is unsustainable and the failure of our political leaders to reach a consensus on how to change course. This can’t go on forever – that much is clear.It can go on forever because not everyone “knows” the budget deficit is “unsustainable”. The bond markets clearly do not have the same model as the mainstream economists consider them to use. The fact is that the bond markets need government debt not the other way around. The requirement that the US federal government issue debt to match its net spending is voluntary only. In financial terms, there is no such requirement. The US government knows that and the bond markets know that. If at any point, the bond markets considered they had more “power” than they actually have and started to make life difficult for the US government (under the current arrangements) those voluntarily-imposed requirements would change very quickly. Japan has had larger deficits to match against public debt issuance for two decades now and they have never had any trouble finding purchasers despite near zero yields over that time. Please read my blog – Who is in charge? – for more discussion on this point. Mankiw then really becomes tragic:

Less obvious, however, is how far we are from the day of reckoning … [the bond market] … trusts our leaders to get the government’s fiscal house in order, eventually, and is waiting patiently while they exhaust the alternatives. But such confidence in American rectitude will not last forever. The more we delay, the bigger the risk that we follow the path of Greece, Ireland and Portugal. I don’t know how long we have before the bond market turns on the United States, but I would prefer not to run the experiment to find out.He will die wondering. But in conflating the US with the EMU nations really provides an insight into why Mankiw is puzzled and asking these questions. The US has zero risk of following in the path of Greece, Ireland and Portugal. The reason is obvious – they operate different monetary systems. The US is a sovereign issuer of its own currency, the other three nations surrendered that luxury when they joined the EMU and operate using a foreign currency (the Euro). There is no legitimate comparison between nations that operate within a fiat currency system where the sovereign state has the monopoly on currency issuance and nations that operate within the Eurozone. The questions that Mankiw is asking reflect that fact that the economic framework he is operating in considers that there is a US risk of insolvency. That should be his fundamental question: Why use a framework that is in denial of the basic reality of the monetary system? If there is no risk of default arising from financial considerations and the federal government can always fund itself without recourse to the bond market – then other questions not asked by Mankiw become more compelling. Such as: how to design an adequate employment-rich fiscal intervention to ensure there is full employment at all times. Conclusion Most of the denial that is around at present among economists arises from the fact that their tool box is insufficient to understand what has actually happened. I sense that there is a lot of ad hoc work going on at present – tinkering around the edges of New Keynesian models to try to incorporate the financial sector more realistically etc. This work will remain fundamentally flawed because the intrinsic nature of these models is inapplicable to the world that we live in. It would be better – in this spirit of admitting there are things that are not known – to abandon those frameworks and adopt frameworks that not only predicted the crisis but can more consistently explain what is going on. It is clear that the economy is riddled with uncertainty and there are lots of guesses and judgements that we make as economists in forming views of the future. But the questions we ask about the uncertainties should be conditioned by a sound understanding of how the monetary system operates and differences between monetary systems. It is a waste of time to ponder whether a nation like the US faces insolvency risk just because Greece does. It is a waste of time designing responses to ward of a bond market strike when those responses damage economic growth and are based on the false assumption that the bond market matters much. The questions Mankiw says are puzzling him just arise from an inadequate framework of analysis. That is where I would be putting my effort. I have run out of time today. I am travelling this afternoon. Tomorrow, my blog will be late and will probably be a short commentary on the Australian federal budget which is presented tomorrow night (19:30). But I won’t get back from my current travels until late tomorrow so the blog will be delayed. That is enough for today!]]>

“From NYT article: “AFTER more than a quarter-century as a professional economist, I have a confession to make: There is a lot I don’t know about the economy. Indeed, the area of economics where I have devoted most of my energy and attention – the ups and downs of the business cycle – is where I find myself most often confronting important questions without obvious answers.”

Typical clueless, spoiled, rich, and overpaid economist. Either doesn’t understand medium of exchange (the difference between currency with no bond attached and the demand deposits from debt), has the dumb idea that real aggregate demand is unlimited so however fast the supply side grows is how fast real GDP will grow, or some combination.

Dean Baker on the 1981-82 recession:

“That was a classic Fed induced recession. The recession came about because the Fed pushed interest rates through the roof. The answer was easy: lower interest rates. When the Fed did lower rates, there was enormous pent-up demand for houses and cars, which sent the economy soaring.”

Were people tricked into debt because of certain price and wage expectations from the 1970’s? What was/is going on if more and more lower and middle class debt is not producing price inflation?

That reminds me….I have to get along to see Mankiw do stand up…..funny guy. This is another in a plethora of articles pondering where oh where did macro get it so wrong….and then refuse to look at not only the alternatives to their thinking (or rather, actively try and tear down competing descriptions of the economy), but how the system works in practice. It really beggars belief, but it is humurous watching these economists running about losing the woods for the trees.

And to comapre 1981-82 with 2008-9….please. Even teh mainstream should call him out for being a complete knucklehead on this one.

As for the great moderation, and at the risk of sending Bill into a rage……a day 1 student in technical analysis would look at the great moderation and conclude that when it breaks, it will break hard, as all trends do. And by god, did it break hard! They might also describe a rising wedge-type formation with a pretty flat top and rising GDP troughs from 1980 onward. Pretty clear stuff.

Why were those troughs rising? Would it possibly have had something to do with the steady juggernaut of a downward trend in the Fed Funds rate? Could it be?!?! How strange that each trough in GDP preceded a massive lurch lower in the Funds rate, with the Funds rate never quite getting back to the previous peak in this ENTIRE period before being called upon again to ultimately reach a new low. Ahhh, those were the days…..days when interest rates had some elasticity relationship with demand for debt. Alas, nowhere to go now….and yet, modern macro doesn’t want to seem to even want to go there….

Mankiw is an economist!!??? I read a story of his once, Principles of Economics, and concluded he wrote fiction.

“What is going on if more and more lower and middle class debt is not producing price inflation?”

My view is that baby boomers are saving for the retirement, and that takes demand out of the economy.

How about

“How long is the long run”.

I would say that a long run that is long than half a generation’s working lives is of no use whatsoever. Everything in economics that is based on longer time periods than that is of *no use* in determining policy – because it would require sacrificing entire lives to the cause.

So if that means we have to have models that deal with a sequence of short runs, then that is how it has to be. Real human lives demand no less.

@Neil Wilson

I have had the impression that economists see the world as a binary state: short run and long run with no time based connection between the two extreme case scenarios. The transition between long run and short run expected outcomes occurs by some kind of magic. Maybe it is also because they see everything as being in equilibrium. The real world is dynamic and continuous. There has to be a time based mechanism by which a short run outcome transitions to a long run outcome. What is needed are models that are time dependent and reduce to the long run scenario as t->infinity and reduce to the short run scenario as t->0 (or similar small number) but describe all states over time and not just these toy states in equilibrium that economists imagine.

@apj

yes it is humourous, … until you realize what kind of influence these people have.

Bill and others,

The following links may be of interest:

John quiggin engages with chartalism

http://johnquiggin.com/2011/05/09/some-propositions-for-chartalists-wonkish/

And Robert Murphy:

http://mises.org/daily/5260/The-UpsideDown-World-of-MMT

“If you then take into account that Mankiw and his ilk preached that the problem of the business cycle was largely solved by inflation targetting monetary policy and passive fiscal policy, I guess the crisis and its aftermath would be confounding.

The “Great Moderation” is a term used by mainstream economists to describe the fact that both GDP growth and inflation were less volatile in the period from the mid-1980s to the onset of the financial crisis.”

The “Great Moderation” was nothing more than trying to use more and more debt (mostly private but some gov’t) to stabilize and grow an economy and to make sure workers did not retire too soon or at all. Unfortunately, almost all economists can’t understand the concept of too much debt (whether private or gov’t).

And, “The Great Moderation became the norm in mainstream economics and further distracted them from seing what was really going on in financial markets which ultimately manifested as the global financial crisis.”

Replace “financial crisis” with a “too much debt crisis.”

“Taking U.S. performance over the past 50 years as a benchmark, the potential for welfare gains from better long-run, supply side policies exceeds by far the potential from further improvements in short-run demand management.”

Typical clueless, spoiled, rich, and overpaid economist with no concept of what happened during The Great Depression or anything before it. He should be paid about USD $10,000 per year or less with no benefits so he can understand the demand side.

Amazing that Mankiw would put question 3 in writing and have it published in the NY Times!

“What the “Great Moderation” left us with was a major financial collapse leading to a collapse in private spending and the recession that ensued. Along the way it created a huge private debt burden and increasing income inequality.”

Price inflation targeting and NGDP targeting without targeting the amount of debt is nothing more than an excuse to allow the spoiled and the rich to use positive productivity growth and cheap labor to get the labor market oversupplied so they can exploit it to “steal” the real earnings growth and retirement of the lower and middle class.

Hehe… Dean Baker gave a commentary on that same article — just mentioning it here because I think Baker has all but signed up to MMT.

http://bit.ly/lHdgup

“After all, the real threat to those holding U.S. government bonds is inflation, not insolvency, unlike the euro zone countries that Mankiw refers to in his piece. The United States can always print more dollars to meet its obligations. Greece cannot do the same with euros.

The idea being pushed by many in policy circles that at some point the bond markets will lose faith in the ability of the U.S. government to pay its debts is absurd on its face. This would be like saying that if I issued iou’s, that were payable in my iou’s, that the markets would be worried about my ability to meet my commitments.”

On the subway this morning I read the latest “Schumpeter” column in the Economist. Like Mankiw’s article Saturday I see this as evidence the “Neo-Classicism” in economics has “advanced” into a Baroque if not Rococo phase where cherubs, clouds and gilding decorate an underlying structure so distorted that it can only be achieved by hanging plaster veneer off the decaying and ancient structure above it.

These guys are doing to economics what “post-modernists” did to architecture thirty years ago: it is solid veneer, a surface that represents nothing but the fantasies or delirium of those who built it.

When the structure above begins to leak, all those frescoes, all that plaster, those angles and cherubs and all that gold plating will come crashing down. Unfortunately it won’t land on those who devised it.

PZ’s post said: “”What is going on if more and more lower and middle class debt is not producing price inflation?”

My view is that baby boomers are saving for the retirement, and that takes demand out of the economy.”

If the baby boomers are saving (emphasis on the “If part”), then who is going into debt and what assumptions about the future are they making?

mdm,

Niether of your two links have addressed these issues with any seriousness. The first one admits as much in his preamble. The second one focuses on an extraneous detail and, because he misunderstands its relevance uses it to make some glib assertions.

John Quiggin’s post is an honest attempt by its author to advance his understanding by posing some questions he’d like to see Bill or someone like him respond to that begins and concludes by soliciting such comments.

Robert Murphy is quite certain he knows all there is to know and attempts to end the conversation with a smirk of superiority.

mankiw doesn’t understand economics, and doesn’t understand the world. example?

read his book, every example, exercise or discussion in microecon is about ice-cream.

where does he live? how many ice-cream there are in that country? Why they produce only ice-cream?

John,

I just meant to provide the links for Bill and anyone else interested. I didn’t mean to imply anything else.

John & mdm

I’m new to MMT but reading Murphy’s critique was very irritating. He seeks to review the accounting relationships but eventually gives way and adds layers of his ideology that by definition are not present in the accounting relationships:

“So the accounting tells us that the right-hand side must get bigger too. It may happen partially because people cut down on consumption and save more (due to higher interest rates and their expectation of higher tax burdens in the future), but it may also happen because private-sector investment goes down. In other words, as the government borrows and spends more, the equation tells us we might see lower private consumption, rising interest rates, and real resources being siphoned out of private investment into pork-barrel spending projects. I can tell my “story” of the dangers of government deficit spending with that equation just fine”

Incidentally, I was just having an argument with someone and I wanted to point out that Britain’s QE didn’t require taxation (yeah, I know… duh). But I came across this video on the Bank of England website:

http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/education/inflation/qe/video.htm

Now, it’s complete rubbish, of course. QE does not — as the BoE robot-woman says — increase private sector spending and investment. But still, I thought this video was interesting from a didactic point-of-view. It clearly says that the central bank creates money ‘electronically’ and gives the general impression that such currency is used to prop up aggregate demand (even if they’re wrong about how this works).

Anyway, maybe others can find a use for it too…

I’ve only briefly read Murphy’s post, hopefully someone will reply in detail but I agree with your assessment. Though in saying that I’d like to see his argument that the “so what” argument addressed.

There’s also the issue of investment and savings and the direction of causality, Murphy uses the conventional direction which MMT rejects, and the use of a barter model – I believe most MMTers would follow Post Keynesians in arguing that the logic of a barter economy is fundamentally different to the current monetary production economy.

I wonder what if Murphy believes that both the private sector and government sector can leverage at the same time? or does he assume that the adjustment process is very quick.

Phillip P

“Now, it’s complete rubbish, of course. QE does not – as the BoE robot-woman says – increase private sector spending and investment.”

For consideration?

“To be sure, there is no proof that QE2 led to the stock-market rise, or that the stock-market rise caused the increase in consumer spending. But the timing of the stock-market rise, and the lack of any other reason for a sharp rise in consumer spending, makes that chain of events look very plausible. The magnitude of the relationship between the stock-market rise and the jump in consumer spending also fits the data. Since share ownership (including mutual funds) of American households totals approximately $17 trillion, a 15% rise in share prices increased household wealth by about $2.5 trillion. The past relationship between wealth and consumer spending implies that each $100 of additional wealth raises consumer spending by about four dollars, so $2.5 trillion of additional wealth would raise consumer spending by roughly $100 billion.

That figure matches closely the fall in household saving and the resulting increase in consumer spending. Since US households’ after-tax income totals $11.4 trillion, a one-percentage-point fall in the saving rate means a decline of saving and a corresponding rise in consumer spending of $114 billion – very close to the rise in consumer spending implied by the increased wealth that resulted from the gain in share prices.”

http://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/feldstein33/English

“Another enigma here is that the alternative view – that in the long run, national income is a function of the quantity of money – has clear and overwhelming substantiating evidence from all economies at all times. Both evidence and standard theory argue that the expansionary open market operations that are the hallmark of quantitative easing, not bank recapitalisation, should have been policy-makers’ first priority last autumn. In the next crisis they must accept that money, not bank credit by itself, is the variable, which matters most to macroeconomic outcomes.”

June 2009

http://standpointmag.co.uk/node/1577

Bit lost here guys, does the debt not have to be repaid at some point? or does it just keep ballooning out forever? what about the interest on the debt isn’t that going to hurt at some point?

Sam the man “Bit lost here guys, does the debt not have to be repaid at some point? or does it just keep ballooning out forever? what about the interest on the debt isn’t that going to hurt at some point?”

The idea is supposed to be that inflation and economic growth means that the ballooning debt never becomes any harder to afford. In the UK the interest on gov debt is currently less than inflation and anyway thanks to quantative easing much of that gov debt is actually owned by the UK gov and so the interest is paid back to its self. If gov of different countries have reciprocal holdings of each other’s debt and so pay interest to each other then that also means that globally gov debt need not become un-affordable. To me the key question is not whether this can be executed but rather whether it is beneficial to do it.

Soooo good. This is the man who posted a piece about his wedding in his NYT column. sheesh.

Here is Yoram Bauman on Mankiw for those who haven’t seen it. Hilarious.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_embedded&hl=en&v=VVp8UGjECt4&gl=US

@ Postkey

Sorry, that should have read that QE does not lead to private sector spending and investment in any direct manner — it may well lead to these outcomes by bumping up the stock market and generating a ‘wealth effect’, but I don’t think that’s how the central banks picture it working. And besides — I don’t think that’s a very desirable outcome.

On this:

“…that in the long run, national income is a function of the quantity of money …”

Urm, isn’t that sort of circular logic. How do they prove that national income is a ‘function’ of the quantity of money. Just because the money supply is high when national income is high this doesn’t imply causality — unless there’s something I’m missing…

Sam the Man:

If you look at the absolute value of the U.S. debt since WWII it NEVER goes down. I take that to mean that we never paid back any of the WWII debt, despite the claims the “Greatest Generation.” What does go down is the debt as a percentage of GDP. Inflation and growth are what takes care of the debt.

stone said: “The idea is supposed to be that inflation and economic growth means that the ballooning debt never becomes any harder to afford.”

GaryD said: “Inflation and growth are what takes care of the debt.”

So what happens if your economy goes from mostly supply constrained to mostly demand constrained and that economy is still trying to grow supply more than demand?

Fed Up “So what happens if your economy goes from mostly supply constrained to mostly demand constrained and that economy is still trying to grow supply more than demand?”

-I guess what happens is that the build of of net financial assets gets employed in commodity speculation creating price spikes in commodities that mean that demand starts becoming more of a constraint. There becomes a financial need for massive inventories of oil, wheat, iron etc that cost a fortune to store and that inventory oscillates in value. Essentially the build up of net financial assets allows genuine real wastefulness to build up (eg inventories of commodities, bloated financial system etc etc). That wastefulness then creates a supply constraint. If almost everyone is employed either as a grain store operative or as a hedge fund manager, then there will not be enough people doing useful jobs and so the supply and demand imbalances will be “cured” :).

PZ, your explanation could be right, but the problem with it is that aggregate demand includes demand for investment goods. If it was just that the boomers were saving for retirement, then why don’t firms take advantage of the pool of savings to invest for the future? This failure of savings to lead to real investment requires explanation. (Not saying that you don’t have an explanation for this; just it needs explanation.)