I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Vignettes of madness

It is the Easter holidays and I am not writing as much today. But there have been some stunning examples of how mad the world has become with respect to matters economic. I present three vignettes of such madness which highlight the way in which lies and outright lies are dominating the policy agendas of governments at the expense of workers and their families. It is also raining outside and getting cooler so good weather for sitting down and writing – holiday notwithstanding.

Madness 101

The first bit of madness came last week with the news that the OECD Urges Japan to Raise Sales Tax. I thought for a moment the OECD had got their dates mixed up and thought it was April 1 (“fools day”). But then I remembered the OECD play the fool all year round so don’t have to wait for a specific day to trigger their madness.

The Wall Street Journal took a typically uncritical approach – which means in financial journalism land – take the press release from the neo-liberal organisation and repeat it without asking any questions which might allow a reader to form a degree of informed skepticism.

These journalists are just mouthpieces for the conservatives.

The OECD considers that Japan will suffer a significant short-term dent in its expected growth as a result of the earthquake/tsunami but that the activity associated with the massive reconstruction effort will boost growth later 2011 and into 2012. I agree with that assessment.

Please read my blog – Earthquake lies – for more discussion on this point.

The OECD estimates, however, suggest that even once real GDP growth recovers as the reconstruction begins, Japan will still experience below-trend economic activity.

Notwithstanding that, the OECD now claims that the Japanese government has to now balance the needs of the reconstruction effort with what they describe as “a critical fiscal situation” (Source). That is, the Japanese government is being bullied into cutting their deficit at a time when growth is likely to be slow, especially in private spending.

The OECD Secretary General claimed (in relation to the Kobe situation) that:

This time, reconstruction spending will have to be combined with efforts to improve the fiscal situation …

The OECD claim that the private sector will have to “shoulder” the burden of the reconstruction – as if losing whole villages and thousands of people isn’t a “burden”.

The reason? They claim that:

In light of the debt situation, this may need to be funded by shifting expenditures and by short-term increases in revenues, appealing to the Japanese people’s sense of solidarity … Tax reform should be spelled out and announced in fiscal year 2011, and tax increases should begin as soon as possible … A doubling in the consumption tax to 10% would be just a first step.

It is at that point you realise how distorted this sort of commentary is. Even by their own estimates private consumption growth is predicted to be significantly negative in 2011 and tepid in 2012. So a further tax impost will slow that down further.

In addition, private investment geared to the domestic market will slow as well.

The OECD claims that “time was running out” for the Japanese government to reduce its public debt. What exactly do they mean by that? Answer: it is left as a nebulous assertion.

What could it mean?

That the Japanese government faces a solvency issue? Answer: impossible – it issues the yen and can meet all debt obligations whenever.

That no-one will want to buy bonds anymore? Answer: so what? The Bank of Japan will always step in if the private bond markets are saturated. What is the likelihood that the private bond market will be saturated. Highly unlikely but irrelevant anyway.

That interest rates will soar? Answer: the Bank of Japan effectively controls or can control all relevant interest rates. Japan has had two decades of growing deficits with rising public debt issuance. Over that period, interest rates have been near zero and inflation hovering on either side of deflation.

Japan has consistently shown that the the neo-liberal panics that public deficits and debt will “run out of time” and cause accelerating inflation and sky-rocketing interest rates are false. Japan proves that rising deficits are not inflationary and that central banks can control interest rates (keeping them near zero) indefinitely.

Interestingly, the OECD noted that the Bank of Japan had kept long-term interest rates low after the disaster and claimed that they should continue to do this “through additional buying of Japanese government bonds”. At present the BOJ is a heavy buyer of Japanese government bonds in the secondary market.

The reality is that they could buy them at issue (in the primary market) if instructed by the Japanese government. The private bond markets know this and this means there will be no reluctance to buy the debt.

But the notion that the reconstruction requires the private sector to “pay” for the government spending is nonsensical and efforts to enforce that stupidity will just damage economic growth and impart unnecessary suffering on people who have endured deep trauma in their lives.

Madness 201

Yesterday, I read a report that Deutsche Bank have some “sovereign risk index” which they mindlessly apply to all nations and make outlandish statements about which nations are about to default.

I cannot make the DB report available so I direct you to the News Limited rag (our daily national newspaper) – The Australian – which carried this story about the DB report on Saturday (April 23, 2011) – US economy just a notch above Greece. It was a syndicated article from the UK Times. It was another mindless reiteration of a media release – no critical scrutiny at all.

The story goes:

US finances are in almost as troubled a state as the worst-hit members of the euro zone, economists say, underscoring the pressing need for Washington to reach agreement on how to reduce the deficit.

A gauge of “sovereign risk” from economists at Deutsche Bank placed the United States just behind Greece, Ireland and Portugal among 14 advanced economies.

The report, from economists led by Peter Hooper, warned that a failure to make substantial political progress on deficit reduction “would substantially raise the risk of a bond market crisis”.

DB = BS

There is no sovereign risk when it comes to the United States. The EMU nations operate within a totally different monetary system in which they have surrendered their currency sovereignty and are exposed to the risk that bond markets will stop lending their governments the necessary cash to continue their deficits.

The United States government can never run out of cash unless the polity stupidly determines that they will artificially restrict their capacity to spend by refusing to raise their self-imposed debt limits.

The DB report claims that the risk of US default is low but that:

Reputation and reserve currency status can be lost, and failure to move US fiscal policy off its currently unsustainable path would certainly increase the risk.

The journalist should have questioned the link between solvency risk and reserve currency status. There is no link. The US government has a low risk of default not because it is a widely used currency around the world.

The reason is has no financial risk is because it is a sovereign issuer of the US. Just like Japan, the UK, Australia, Canada and almost every country – right down to the smallest most unstable nation. None of them have any financial risk of reaching a point where their governments can no longer honour debts denominated in their own currency.

The reserve currency status or otherwise has nothing to do with it. Whenever I read that sort of conclusion – as in the DB report – I conclude the authors do not understand the characteristics of the monetary systems that they are claiming to be experts about.

Madness 301

The Congressional Budget Office has just released (April, 2011) their annual assessment of the impact of the automatic stabilisers on the US government budget balance – The Effects of Automatic Stabilizers on the Federal Budget. You can find the accompanying data set HERE.

They provide a detailed account of how they calculate the impacts of the automatic stabilisers – that is, decompose the budget outcome into structural and cyclical components. They also provide annual and quarterly data.

I was critical of their methodology in this blog – Structural deficits and automatic stabilisers. You should also read this blog – Structural deficits – the great con job! – where I discuss general problems involved in computing structural deficits.

This blog – The dreaded NAIRU is still about! – is also related.

In effect, their methodology leads them to understate the degree of excess capacity (that is, underestimate the GDP gap). But things are bad enough if we just take their downwardly biased estimates at face value.

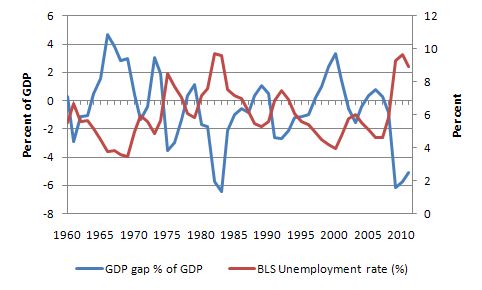

The GDP gap equals actual (or projected) GDP minus potential GDP and the following graph shows the GDP gap as a percentage of GDP (left-hand axis – blue line).

I added the unemployment rate from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics (right-hand axis – red line) to demonstrate the close inverse relationship between movements in real GDP away from potential and the dynamics of the unemployment rate – just in case any of you entertain notions that the variations in the unemployment rate are driven by changing preferences of individuals (the neo-liberal story).

The mirror image relationship is compelling. What does it suggest? The basic – the first rule – that you learn in macroeconomics is that – spending generates income and output. Cut spending and you cut output.

In the short-term, cutting output increases the real GDP gap. If that gap rises persistently, then eventually the potential output level also falls as investment is curtailed. Over this entire period, unemployment worsens or becomes entrenched at high levels. The costs of maintaining output gaps of this size – the daily costs of lost income – are huge.

No legislature in their right minds would give a second’s thought to cutting spending with such an output gap. That is Madness 301.

Not only will they worsen the situation in the interim but they will also be imposing lifetime costs on the youth who are either jobless as a consequence of the lack of opportunities or whose parents are in the same position.

Conclusion

Short blog today – happy holiday if you are in a position to enjoy it.

I also recognise all the soldiers who died on both sides during the Anzac invasion. Today is not only Easter Monday but also Anzac Day. Once you learn more about it you realise how poorly managed our front-line troops were by the pompous and incompetent British generals who were just exerting their colonial power.

Note on Saturday Quiz

I note that some people are making claims about the lack of economic content in the Saturday Quiz and that they are bored with it.

First, the questions all test economic understanding. Words are important however and the use of terms is important. Part of the challenge I try to set for your enjoyment relates to being concise about terminology.

Second, the quiz is purely voluntary and provided free of charge. If you don’t like it – it is quite simple – don’t do it! Better that way than clogging up the comments section with statements about being bored etc.

That is enough for today!

Bill

I’m new to your blog and a total novice in macroeconomics. As a novice, I didn’t expect to be up to comprehension required for #2 & #5. This week was my second quiz and I put a lot more effort into understanding how I came up with wrong answers.

For example regarding #1: I learned to distinguish between “monetary base” and “money supply” (with the help of Wikipedia); that aggregate demand is the sum of public & private spending (I was fuzzy on that obvious fact); and how banks “make loans and get reserves” as opposed to “first banks get reserves to make loans”. Rereading some of your weekly blogs, I found out that mainstream economists think inflation is more likely to result from money creation than debt-issuance. The question made me think about how to use what I thought I understood. I know there is a difference between a superficial understanding and the ability to use knowledge analytically. I’m not unhappy with my progress!

I enjoy your analysis of current news items. These are also instructive in the application of MMT concepts.

For people who want to invest the effort, your blog is an excellent place to learn how the economy works.

I appreciate your rigor, clarity, and most of all your effort to make this all possible.

I had thought about getting textbook on macroeconomics before finding your blog.

Now, I’m really glad I found this site first. I would have spent a lot of time learning the wrong things!

Cheers

Bill, the chart is even more powerful when you invert the output gap series and add the deficit. Quite simply, the gap leads the deficit – Reliably, consistently, and over a long, long time frame. You don’t need MMT or anything else to appreciate what this means – quite simply, while the deficit is the output of revenues and expenses, it really is more about the progress of the macro economy, and the effect it has on those variables via stabilisers and compounding of activity. Makes you wonder why the conservative side of things don’t get it, or why the progressives aren’t more effective at calling them out on their expansion through austerity claims.

Dear Mr Mitchell

Peter and Paul both owe you 1000. Peter only pays you back 500, so he has partially defaulted. Paul pays you back the full 1000, but those 1000 are worth only half of what they were worth when you lent them to him. In both cases, you get back only half your money. This illustrates that there are two ways of defaulting: not paying back and paying back in inflated dollars.

You hammer on the fact that governments which enjoy monetary sovereignty can’t become insolvent. I quite agree. However, they can default by paying off their debt in inflated currency. An historical example was the Weimar Republic. It managed to wipe out a considerable portion of its war debt through the hyperinflation of the 1920’s.

The neo-liberal fear of growing government debts may be seen as quite logical once we bear in mind that economic liberalism is primarily about the defense of the interests of the wealthy. Many wealthy people are lenders, and their net worth can be reduced by debt-ridden governments trying to default on their public debt through inflation. Of course, many wealthy people are borrowers as well because nearly all business have debts.

Anyway, my point is that insolvency and default on debt are different things for a state which has monetary sovereignty. James

James, would you say then that governments are defaulting every year given ‘any’ positive number for the inflation rate?

There is a post about Weimar above right, under Categories, which was a completely different circumstance. It’s worth a read given the vast differences between current conditions, and those that enable a hyperinflation.

James, I think it is very simple: do not lend you money! Spend it! And nobody will cry.

Weimar Germany, Hyperinflations, Government debt, defaulting on loan repayments, implying that the money base and money supply are one in the same…… Oh Dear..Her we go again.

Dear apj

Low inflation has been a fact of life in nearly every country for decades now. It reveals no evil intentions on anybody’s part, and it is perfectly predictable. I merely wanted to point out that holders of government bonds can’t always be sure of getting their money back without losing purchasing power just because governments with their own currency can’t go insolvent.

As to the hyperinflation of the 1920’s in the Weimar Republic, I’m not sure what the causes were, but I doubt very much that bondholders were happy because they received their full nominal value back. James

Bill,

I think the people who are bored with the quiz must be the people who already have a thorough understanding of MMT. For those of us who haven’t quite got it all yet, the quiz is invaluable. Keep at it. It is much appreciated and I’m sure a lot of others would agree.

Cheers,

Cooper

If MMT is ever going to get anywhere it will need an army of followers with answers to pretty much any question the opposition can throw at them.

The Saturday Quiz and the solutions Bill provides are a very good way to arm people with the information they need to bring down the orthodoxy.

To the afflicted the Saturday Quiz is addictive, like pulling the lever on a poker machine: you know the result will (usually) be a crushing blow to your self esteem, but every now and then, you score a 5, and that’s the random reinforcement that feeds the addiction.

I just hope Bill doesn’t demand that we buy chips (with real $) to play.

Seriously though, the quiz and the follow-up is a great learning tool (as Alan says), and at this stage of MMT’s expansion, it’s invaluable.

“Weimar Germany, Hyperinflations, …… Oh Dear..Her we go again.”

Alan, many new people read and are interested in this blog; we don’t know all the preceding questions

and answers. I’m interested in what James Schipper has said. These are the questions I ask (though I have once been told to “read xxx from 1887”, which is a bit arrogant, really. Bill, though, has answered some of my points politely and respectfully!).

If this is supposed to be a club of like-minded, well-researched, opinionated folk, then so be it. I wouldn’t be admitted to that club. If it is for interested, though less well-read, open-minded readers, I’ll carry on reading and learning. From the repeated comments as well as the erudite, learned ones.

James @ 10:48

“I merely wanted to point out that holders of government bonds can’t always be sure of getting their money back without losing purchasing power just because governments with their own currency can’t go insolvent.”

I realise you were just making a point, which sounds fair enough to me (ignoring Weimar).

But what do the bond vigilantes know that the media mouthpieces don’t ?

The last auction of 10 year US Treasuries was oversubscribed, driving the yield down to something around 3%.

I think they know that the insolvency hype is total BS, and don’t seem to be too concerned about inflation either.

Dear Elizabeth (at 2011/04/26 at 20:19)

All commentators are welcome here as long as they debate the points and do not get personal. There is no club for the cognoscenti operating here.

best wishes

bill

Elizabeth,

I won’t speak for Alan, but I must confess that when I first read James’ post I too had that “here we go again” feeling: on all the MMT blogs which allow comments, the hyperinflations of the Weimar Republic and Zimbabwe are frequently presented, triumphantly, as not just the last nail in the coffin of MMT, but the brass handles and floral tribute. It was not exactly an original contribution.

James’ question however was a genuine one as shown by subsequent comment.

Like apj said, Bill has an excellent essay in the archives pointing out the dis-similarities, and why the Weimar and Zimbabwe experiences are not relevant. But the billyblog archive is huge, and I guess nobody can expect newcomers to be up to speed on all the old worn-out debating points before sticking their necks out and posting comments, especially under their real names !

Clearly, what billyblog needs is a FAQ section.

I do know that Weimar and Zimbabwe would be amongst the first questions addressed, preceded only by the usual fears of MMT and inflation, which, sadly, Paul Krugman is yet to get his head around.

Thanks for your replies. For John Armour “The last auction of 10 year US Treasuries was oversubscribed, driving the yield down to something around 3%.”

I read something over the weekend in Zero Hedge about China

http://www.zerohedge.com/article/china-proposes-cut-two-thirds-its-3-trillion-usd-holdings

Is this relevant?

Regards,

Elizabeth

Hi Elizabeth,

I wouldn’t venture an opinion on the implications of China diversifying it’s foreign reserves in the manner described in that article. Like you, I’m a relative newcomer to the wonderful world of monetary mechanics.

I will say however that some of the things in that article surprised me. I’ve always understood that China’s holdings of US Treasuries were only about 1 trillion, with Japan’s a bit less. I think the figure of 3 trillion might be China’s total foreign holdings, denominated in US dollars. That being so, the wording was a bit misleading.

I’m also wary of articles that describe the US Fed’s quantitative easing as “printing money”. I start to look for an agenda. QE is just an asset swap between the Fed and commercial banks. Even Bernanke tried to straighten out the financial journalists on this one (to little effect it seems). If the writer can’t get the basics right, I wonder about the rest.

Cheers, John

@ John Armour Tuesday, April 26, 2011 at 21:27

Second that: often have wished the subject search through the archive (growning daily) was better defined. Wish I could search by commentator too! Still, learning should be fun and that’s what I like best about billy blog.

Cheers,

jrbarch

@James Schipper

Yes, hyperinflation is in effect a type of default. But what’s your point? The USA has low inflation and also has low inflation expectations, check out TIPS yields. There is no default risk, however you want to define a default.

@Bill Mitchell

I don’t think finance journalists are mouth pieces for conservatives per se. Financial publications exists these days solely to provide content so as to get eye balls so as to make money. It is not just the News ltd press. Have a look at business spectator, IMO a left of centre publication. Same deal. They report rent a quotes from unaccountable pundits with miserable forecasting records, and all of this without any critical analysis of the claims being made. Thus, press releases and so on and regurgitated without any analysis. To be honest I think you should start playing the game the and send press releases out from your economic research centre.

Will the US have to keep unemployment at a permanently high level to keep inflation at bay? A weakening dollar and probable intensification of the competition for natural resources seem likely to put upward pressure on the prices of goods (as import prices will be higher in US dollar terms).