I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Are things improving for US workers?

I have been tied up most of today so have little time to write my blog. I was interested in the most recent US labour market data which suggested that in net terms there was some improvement in employment growth. I wondered how this translated into increasing the probability that an unemployed person might get a job and how likely it was that an employed person would lose their job. The recovery is clearly nascent and risks being squashed by the moronic leadership being shown in the US Congress at the moment. So how far has the US labour market come since the recession started? Gross flows analysis allows us to gain insights into this sort of question. So are things improving in the US?

The nature of macroeconomic demand constraints on the labour market is that individuals are powerless to do anything about them. If there are not enough jobs then that is binding on individuals. The mainstream textbook models which says that workers can improve their prospects by agreeing to work for lower than the going wage does not improve their chances of gaining employment in a demand-constrained economy.

Please read my blog – What causes mass unemployment? – for more discussion on this point.

The problem with the political shenanigans going on in the US at present is that they appear to be in denial about the realities of an economy that has been severely traumatised and now, still very delicate, is showing signs of recovery.

To help us determine how much recovery has been occurring I wondered how much easier it is for an unemployed worker to gain employment now relative to say a year ago? Are new entrants into the labour market more likely to gain employment? What is the chance of a worker losing their job?

These sorts of questions can be answered by examining the Gross labour flows that are available from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics. I updated my databases this morning and now have data up to March 2011.

To fully understand the way gross flows are assembled and the transition probabilities calculated you might like to read these blogs – What can the gross flows tell us? and More calls for job creation – but then. For earlier US analysis see this blog – Jobs are needed in the US but that would require leadership

By way of summary, gross flows analysis allows us to trace flows of workers between different labour market states (employment; unemployment; and non-participation) between months. So we can see the size of the flows in and out of the labour force more easily and into the respective labour force states (employment and unemployment).

The various inflows and outflows between the labour force categories are expressed in terms of numbers of persons. But a useful alternative presentation is to compute transition probabilities, which are the probabilities that transitions (changes of state) occur. For example, what is the probability that a person who is unemployed now will enter employment next period.

So if a transition probability for the shift between employment to unemployment is 0.05, we say that a worker who is currently employed has a 5 per cent chance of becoming unemployed in the next month. If this probability fell to 0.01 then we would say that the labour market is improving (only a 1 per cent chance of making this transition).

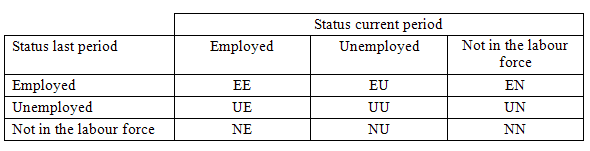

The following table shows the schematic way in which gross flows data is arranged each month – sometimes called a Gross Flows Matrix. For example, the element EE tells you how many people who were in employment in the previous month remain in employment in the current month. Similarly the element EU tells you how many people who were in employment in the previous month are now unemployed in the current month. And so on. This allows you to trace all inflows and outflows from a given state during the month in question.

The transition probabilities are computed by dividing the flow element in the matrix by the initial state. For example, if you want the probability of a worker remaining unemployed between the two months you would divide the flow (U to U) by the initial stock of unemployment. If you wanted to compute the probability that a worker would make the transition from employment to unemployment you would divide the flow (EU) by the initial stock of employment. And so on.

So for the 3 Labour Force states we can compute 9 transition probabilities reflecting the inflows and outflows from each of the combinations.

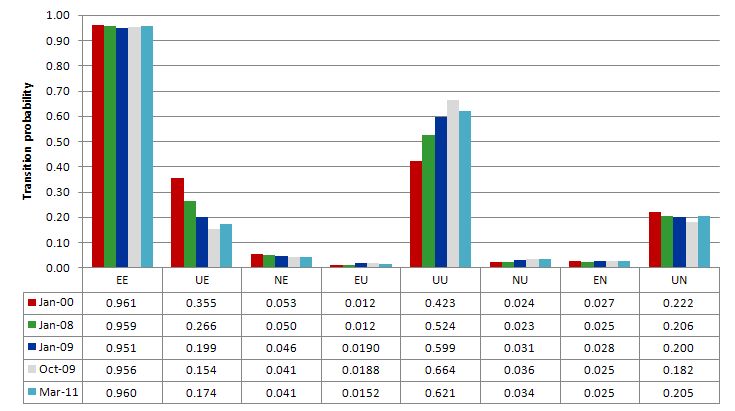

The first graph compares the US transition probabilities for various months during the crisis up until March 2011 (see the accompanying Table for values). The data is from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics. I also include the January 2000 observation which is the month when the chances of leaving unemployment for employment (UE) was the highest in this data set (since 1990).

The inclusion of October 2009 is because it was the month with the lowest UE transition during the crisis. January 2009 was the lowest EE transition probability.

The data shows that there has been slight improvement in the EE probability – that is, the likelihood an employment person will remain employed in the next month (not necessarily with the same employer though).

Significantly, there has been definite improvement in the chances of an unemployed worker gaining employment relative to October 2009. They now have a 17.4 per cent chance instead of a 15.4 per cent chance.important point is that

But the important point to note is that the value for January 2000 was a peak (0.355) and the transition probability has been declining in waves since then. A worker now has around 1/2 the chance of gaining work compared to that peak. In Australia this probability is currently around 25 percent.

The EU probability has fallen since the depth of the crisis but is still above its historical average.

Workers currently not in the labour force (which includes new entrants about to enter) have a much higher likelihood of becoming unemployed than employed should they choose to participate in the labour force.

Overall, the data suggests some slight improvement in the US labour market but it is still performing well below its pre-crisis status.

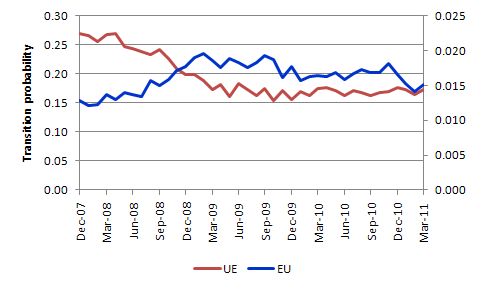

The next graph shows the transitions into and out of unemployment since December 2007. What is striking about the time series is that apart from the initial plunge where it becoming much harder for an unemployed worker to gain employment and much easier for an employed worker to become unemployed, the transitions are very stable over this 3 and a quarter year period.

This tells us that the labour market is stuck in a very persistent recessed state with only slight improvements occurring. In other words, the recovery is very drawn out.

Cutting public spending in an environment as fragile as this is likely to set the recovery back if not put it in reverse.

You might like to compare these results with those I produced recently for Australia which I wrote about in this blog – Australian Labor Government abandons its roots.

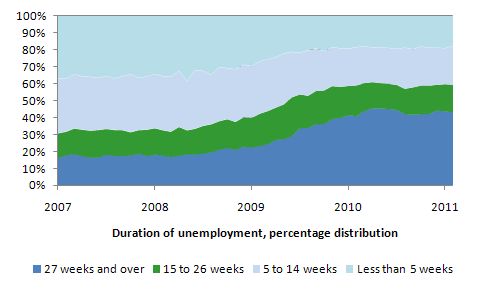

The problem that is encountered when you get persistent stagnant outcomes such as are demonstrated by this data is that short-term unemployment transitions into long-term unemployment with associated skill loss and a range of other financial problems (for example, asset loss through savings exhaustion, mortgage default). These then compound the social and personal costs which include increased health problems, increased family breakdown and more.

The US Bureau of Labor Statistics tell us that in January 2007, the average duration of a spell of unemployment in the US was 16.3 weeks. In March 2011 an unemployed person on average was in that state for 39 weeks and this duration is rising.

The following graph shows the percentage distribution of the duration of unemployment and is taken from this article from the BLS – Duration of unemployment in February 2011.

The BLS say that in February 2011:

… 43.9 percent of unemployed persons had been jobless for 27 weeks or more. This group made up 43.8 percent of unemployed persons in January. In February 2010, 41.0 percent of the unemployed had been jobless for 27 weeks or longer. The number of long-term unemployed (those jobless for 27 weeks or more) was 6.0 million in February 2011.

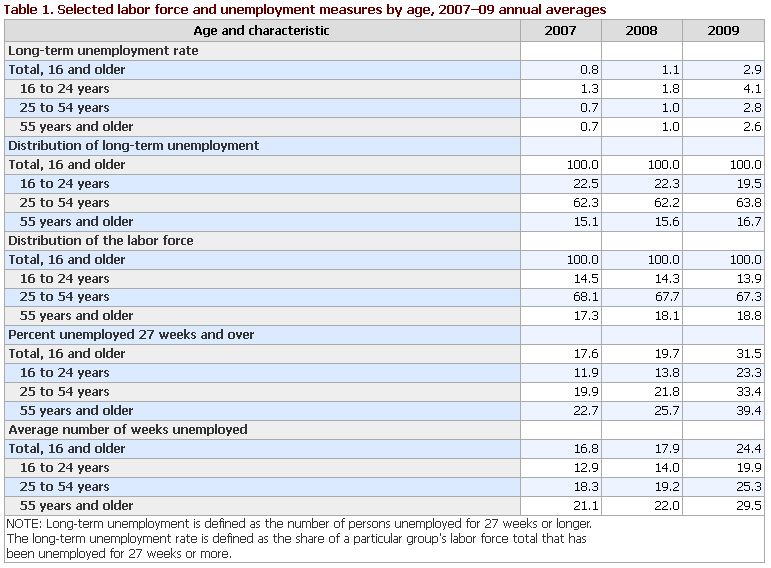

The following table is taken from BLS Long-term unemployment experience of the jobless and lets you see how long-term unemployment has evolved across the age distribution.

The Table was included in thisBLS article – Long-term unemployment experience of the jobless – which I haven’t time today to discuss in detail. But a salient fact from that article is that:

Younger workers were overrepresented among the long-term jobless in 2009, making up 19.5 percent of all persons unemployed for 27 weeks or more, compared with 13.9 percent of the labor force …

At first glance, it appears that younger workers in the current economic downturn have been hit particularly hard by long-term unemployment because of their high long-term unemployment rate and their disproportionate share of the long-term jobless.

So America’s future!

Radio discussion on Australian government’s flawed fiscal strategy

I did a long interview yesterday with the independent current affairs radio program – The Wire on the current debate surrounding the Australian Treasurer’s claims that the budget in May has to be even tighter to get to surplus in the wake of the collapse in revenue as a result of the economy slowing down.

The Wire describe the segment – Rivers of gold dry up in this way:

Treasurer Wayne Swan addressed a media conference in Brisbane, in his last major address before handing down his 4th budget in May. It came to no surprise that he was warning us to expect a tough budget, in the wake of natural disasters in Australia and Japan. Besides dealing with the predicted nine billion dollar blow to the economy caused by cyclones floods and tsunamis, the treasurer also says the next wave of the mining boom won’t bring in the so-called rivers of gold we say during the Howard years. But is the state of the economy just due to unforseen circumstances or is it as Tony Abbott said-just bad economic management? Featuring Bill Mitchell, Director of the Centre of full Employment and Equity at the University of Newcastle.

You can hear a reasonably full excerpt of that interview – HERE if you are interested.

Conclusion

It is now only slightly easier to transit from unemployment to employment in the US compared to a year ago but much harder than at the onset of the crisis. An unemployed American worker is much more likely to drop out of the labour force than to enter employment.

With the youth now suffering chronic long-term unemployment now is the time to be creating jobs not undermining them.

Some leadership is required.

I have run out of time today.

That is enough for today!

Great to hear you in radio land Bill. I saw Marshall’s interview on BNN a couple of days ago doing likewise via the New Economic Perspectives site in respect of Obama’s proposed deficit reducction plan.

I have to say that BillyBlog is the most accessible and ‘in depth’ site I’ve come across on Modern Monetary Theory although I find Pragmatic Capitalism very good too.

There seems to have been a deliberate intent for MMT developers to start blogging to get their message across a couple of years ago but although I’ve seen articles and comments from Scott, Randall and Stephanie and others in various places plus, of course, their contributions to New Economic Perspectives, it seems to me that that if these guys and gals could adopt a similar approach to yours then the message would become that much louder.

I just want to say that I have only recently discovered your blog. And, I would like to say how much I appreciate the opportunity to learn, in greater detail, how important aspects of the economy function. So, thank you for all the work you put into making that possible for me.

I live in the USA and it is great to have acesse to your current evaluation of our employment status. I liked the way you explained where the data came from, how you analyzed it, and then how to interpret the results. So much more useful than the usual way these are reported in the media i.e. this month x went up/down 0.1%. I learned a lot!