Here are the answers with discussion for this Weekend’s Quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of Modern…

Saturday Quiz – November 6, 2010 – answers and discussion

Here are the answers with discussion for yesterday’s quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of modern monetary theory (MMT) and its application to macroeconomic thinking. Comments as usual welcome, especially if I have made an error.

Question 1:

The price at which the central bank provides reserves to the commercial banks is restricted by its target monetary policy rate.

The answer is True.

The facts are as follows. First, central banks will always provided enough reserve balances to the commercial banks at a price it sets using a combination of overdraft/discounting facilities and open market operations.

Second, if the central bank didn’t provide the reserves necessary to match the growth in deposits in the commercial banking system then the payments system would grind to a halt and there would be significant hikes in the interbank rate of interest and a wedge between it and the policy (target) rate – meaning the central bank’s policy stance becomes compromised.

Third, any reserve requirements within this context while legally enforceable (via fines etc) do not constrain the commercial bank credit creation capacity. Central bank reserves (the accounts the commercial banks keep with the central bank) are not used to make loans. They only function to facilitate the payments system (apart from satisfying any reserve requirements).

Fourth, banks make loans to credit-worthy borrowers and these loans create deposits. If the commercial bank in question is unable to get the reserves necessary to meet the requirements from other sources (other banks) then the central bank has to provide them. But the process of gaining the necessary reserves is a separate and subsequent bank operation to the deposit creation (via the loan).

Fifth, if there were too many reserves in the system (relative to the banks’ desired levels to facilitate the payments system and the required reserves then competition in the interbank (overnight) market would drive the interest rate down. This competition would be driven by banks holding surplus reserves (to their requirements) trying to lend them overnight. The opposite would happen if there were too few reserves supplied by the central bank. Then the chase for overnight funds would drive rates up.

In both cases the central bank would lose control of its current policy rate as the divergence between it and the interbank rate widened. This divergence can snake between the rate that the central bank pays on excess reserves (this rate varies between countries and overtime but before the crisis was zero in Japan and the US) and the penalty rate that the central bank seeks for providing the commercial banks access to the overdraft/discount facility.

So the aim of the central bank is to issue just as many reserves that are required for the law and the banks’ own desires.

Now the question seeks to link the penalty rate that the central bank charges for providing reserves to the banks and the central bank’s target rate. The wider the spread between these rates the more difficult does it become for the central bank to ensure the quantity of reserves is appropriate for maintaining its target (policy) rate.

Where this spread is narrow, central banks “hit” their target rate each day more precisely than when the spread is wider.

So if the central bank really wanted to put the screws on commercial bank lending via increasing the penalty rate, it would have to be prepared to lift its target rate in close correspondence. In other words, its monetary policy stance becomes beholden to the discount window settings.

The best answer was True because the central bank cannot operate with wide divergences between the penalty rate and the target rate and it is likely that the former would have to rise significantly to choke private bank credit creation.

You might like to read this blog for further information:

- US federal reserve governor is part of the problem

- Building bank reserves will not expand credit

- Building bank reserves is not inflationary

Question 2:

The Australian dollar is currently appreciating strongly against many key currencies and this has put pressure on our international competitiveness. Given the terms of trade are so strong, a cut in wages and the rate of inflation would be the way to restore competitiveness. This would help maintain strong export growth.

The answer is Maybe.

This question also applies to the EMU nations who cannot adjust their nominal exchange rate but are seeking export-led demand boosts as they cut government spending.

The temptation is to accept the dominant theme that is emerging from the public debate is telling us.

However, deflating an economy under these circumstance is only part of the story and does not guarantee that a nation’s competitiveness will be increased.

We have to differentiate several concepts: (a) the nominal exchange rate; (b) domestic price levels; (c) unit labour costs; and (d) the real or effective exchange rate.

It is the last of these concepts that determines the “competitiveness” of a nation. This Bank of Japan explanation of the real effective exchange rate is informative. Their English-language services are becoming better by the year.

Nominal exchange rate (e)

The nominal exchange rate (e) is the number of units of one currency that can be purchased with one unit of another currency. There are two ways in which we can quote a bi-lateral exchange rate. Consider the relationship between the $A and the $US.

- The amount of Australian currency that is necessary to purchase one unit of the US currency ($US1) can be expressed. In this case, the $US is the (one unit) reference currency and the other currency is expressed in terms of how much of it is required to buy one unit of the reference currency. So $A1.60 = $US1 means that it takes $1.60 Australian to buy one $US.

- Alternatively, e can be defined as the amount of US dollars that one unit of Australian currency will buy ($A1). In this case, the $A is the reference currency. So, in the example above, this is written as $US0.625= $A1. Thus if it takes $1.60 Australian to buy one $US, then 62.5 cents US buys one $A. (i) is just the inverse of (ii), and vice-versa.

So to understand exchange rate quotations you must know which is the reference currency. In the remaining I use the first convention so e is the amount of $A which is required to buy one unit of the foreign currency.

International competitiveness

Are Australian goods and services becoming more or less competitive with respect to goods and services produced overseas? To answer the question we need to know about:

- movements in the exchange rate, ee; and

- relative inflation rates (domestic and foreign).

Clearly within the EMU, the nominal exchange rate is fixed between nations so the changes in competitiveness all come down to the second source and here foreign means other nations within the EMU as well as nations beyond the EMU.

There are also non-price dimensions to competitiveness, including quality and reliability of supply, which are assumed to be constant.

We can define the ratio of domestic prices (P) to the rest of the world (Pw) as Pw/P.

For a nation running a flexible exchange rate, and domestic prices of goods, say in the USA and Australia remaining unchanged, a depreciation in Australia’s exchange means that our goods have become relatively cheaper than US goods. So our imports should fall and exports rise. An exchange rate appreciation has the opposite effect which is what is occurring at present.

But this option is not available to an EMU nation so the only way goods in say Greece can become cheaper relative to goods in say, Germany is for the relative price ratio (Pw/P) to change:

- If Pw is rising faster than P, then Greek goods are becoming relatively cheaper within the EMU; and

- If Pw is rising slower than P, then Greek goods are becoming relatively more expensive within the EMU.

The inverse of the relative price ratio, namely (P/Pw) measures the ratio of export prices to import prices and is known as the terms of trade.

The real exchange rate

Movements in the nominal exchange rate and the relative price level (Pw/P) need to be combined to tell us about movements in relative competitiveness. The real exchange rate captures the overall impact of these variables and is used to measure our competitiveness in international trade.

The real exchange rate (R) is defined as:

R = (e.Pw/P) (2)

where P is the domestic price level specified in $A, and Pw is the foreign price level specified in foreign currency units, say $US.

The real exchange rate is the ratio of prices of goods abroad measured in $A (ePw) to the $A prices of goods at home (P). So the real exchange rate, R adjusts the nominal exchange rate, e for the relative price levels.

For example, assume P = $A10 and Pw = $US8, and e = 1.60. In this case R = (8×1.6)/10 = 1.28. The $US8 translates into $A12.80 and the US produced goods are more expensive than those in Australia by a ratio of 1.28, ie 28%.

A rise in the real exchange rate can occur if:

- the nominal e depreciates; and/or

- Pw rises more than P, other things equal.

A rise in the real exchange rate should increase our exports and reduce our imports.

A fall in the real exchange rate can occur if:

- the nominal e appreciates; and/or

- Pw rises less than P, other things equal.

A fall in the real exchange rate should reduce our exports and increase our imports.

In the case of the EMU nation we have to consider what factors will drive Pw/P up and increase the competitive of a particular nation.

If prices are set on unit labour costs, then the way to decrease the price level relative to the rest of the world is to reduce unit labour costs faster than everywhere else.

Unit labour costs are defined as cost per unit of output and are thus ratios of wage (and other costs) to output. If labour costs are dominant (we can ignore other costs for the moment) so total labour costs are the wage rate times total employment = w.L. Real output is Y.

So unit labour costs (ULC) = w.L/Y.

L/Y is the inverse of labour productivity(LP) so ULCs can be expressed as the w/(Y/L) = w/LP.

So if the rate of growth in wages is faster than labour productivity growth then ULCs rise and vice-versa. So one way of cutting ULCs is to cut wage levels which is what the austerity programs in the EMU nations (Ireland, Greece, Portugal etc) are attempting to do.

But LP is not constant. If morale falls, sabotage rises, absenteeism rises and overall investment falls in reaction to the extended period of recession and wage cuts then productivity is likely to fall as well. Thus there is no guarantee that ULCs will fall by any significant amount.

Further, the reduction in nominal wage levels threatens the contractual viability of workers (with mortgages etc). It is likely that the cuts in wages would have to be so severe that widespread mortgage defaults etc would result. The instability that this would lead to makes the final outcome uncertain.

Given all these qualifications, the answer is maybe (but undesirable).

You might like to read this blog for further information:

Question 3:

If the budget deficit rises then government policy is becoming more expansionary and this carries the risk that nominal aggregate spending growth might exceed the real capacity of the economy to respond by increasing real output.

The answer is False.

Again this question has two premises – a statement and a related consequence. In this case the statement that “If the budget deficit rises then government policy is becoming more expansionary” is false and the related consequence that “this carries the risk that nominal aggregate spending growth might exceed the real capacity of the economy to respond by increasing real output.” is true.

Taken together the answer is false.

First, it is clearly central to the concept of fiscal sustainability that governments attempt to manage aggregate demand so that nominal growth in spending is consistent with the ability of the economy to respond to it in real terms. So full employment and price stability are connected goals and MMT demonstrates how a government can achieve both with some help from a buffer stock of jobs (the Job Guarantee).

Second, the statement that a “If government net spending increases (rising budget deficit) then policy is becoming more expansionary” is exploring the issue of decomposing the observed budget balance into the discretionary (now called structural) and cyclical components. The latter component is driven by the automatic stabilisers that are in-built into the budget process.

The federal budget balance is the difference between total federal revenue and total federal outlays. So if total revenue is greater than outlays, the budget is in surplus and vice versa. It is a simple matter of accounting with no theory involved. However, the budget balance is used by all and sundry to indicate the fiscal stance of the government.

So if the budget is in surplus it is often concluded that the fiscal impact of government is contractionary (withdrawing net spending) and if the budget is in deficit we say the fiscal impact expansionary (adding net spending).

Further, a rising deficit (falling surplus) is often considered to be reflecting an expansionary policy stance and vice versa. What we know is that a rising deficit may, in fact, indicate a contractionary fiscal stance – which, in turn, creates such income losses that the automatic stabilisers start driving the budget back towards (or into) deficit.

So the complication is that we cannot conclude that changes in the fiscal impact reflect discretionary policy changes. The reason for this uncertainty clearly relates to the operation of the automatic stabilisers.

To see this, the most simple model of the budget balance we might think of can be written as:

Budget Balance = Revenue – Spending.

Budget Balance = (Tax Revenue + Other Revenue) – (Welfare Payments + Other Spending)

We know that Tax Revenue and Welfare Payments move inversely with respect to each other, with the latter rising when GDP growth falls and the former rises with GDP growth. These components of the budget balance are the so-called automatic stabilisers

In other words, without any discretionary policy changes, the budget balance will vary over the course of the business cycle. When the economy is weak – tax revenue falls and welfare payments rise and so the budget balance moves towards deficit (or an increasing deficit). When the economy is stronger – tax revenue rises and welfare payments fall and the budget balance becomes increasingly positive. Automatic stabilisers attenuate the amplitude in the business cycle by expanding the budget in a recession and contracting it in a boom.

So just because the budget goes into deficit doesn’t allow us to conclude that the Government has suddenly become of an expansionary mind. In other words, the presence of automatic stabilisers make it hard to discern whether the fiscal policy stance (chosen by the government) is contractionary or expansionary at any particular point in time.

To overcome this uncertainty, economists devised what used to be called the Full Employment or High Employment Budget. In more recent times, this concept is now called the Structural Balance. The change in nomenclature is very telling because it occurred over the period that neo-liberal governments began to abandon their commitments to maintaining full employment and instead decided to use unemployment as a policy tool to discipline inflation.

The Full Employment Budget Balance was a hypothetical construct of the budget balance that would be realised if the economy was operating at potential or full employment. In other words, calibrating the budget position (and the underlying budget parameters) against some fixed point (full capacity) eliminated the cyclical component – the swings in activity around full employment.

So a full employment budget would be balanced if total outlays and total revenue were equal when the economy was operating at total capacity. If the budget was in surplus at full capacity, then we would conclude that the discretionary structure of the budget was contractionary and vice versa if the budget was in deficit at full capacity.

The calculation of the structural deficit spawned a bit of an industry in the past with lots of complex issues relating to adjustments for inflation, terms of trade effects, changes in interest rates and more.

Much of the debate centred on how to compute the unobserved full employment point in the economy. There were a plethora of methods used in the period of true full employment in the 1960s. All of them had issues but like all empirical work – it was a dirty science – relying on assumptions and simplifications. But that is the nature of the applied economist’s life.

As I explain in the blogs cited below, the measurement issues have a long history and current techniques and frameworks based on the concept of the Non-Accelerating Inflation Rate of Unemployment (the NAIRU) bias the resulting analysis such that actual discretionary positions which are contractionary are seen as being less so and expansionary positions are seen as being more expansionary.

The result is that modern depictions of the structural deficit systematically understate the degree of discretionary contraction coming from fiscal policy.

You might like to read these blogs for further information:

Question 4:

If all national governments simultaneously run public surpluses then it is not possible for all their private domestic sectors to save overall.

The answer is True.

The question tests a knowledge of the sectoral balances and their interactions, the behavioural relationships that generate the flows which are summarised by decomposing the national accounts into these balances, and the constraints that is placed on the behaviour within the three sectors that is evident in the requirement that the balances must add up to zero as a matter of accounting.

Once again, here are the sectoral balances approach to the national accounts.

We can view the basic income-expenditure model in macroeconomics in two ways: (a) from the perspective of the sources of spending; and (b) from the perspective of the uses of the income produced. Bringing these two perspectives (of the same thing) together generates the sectoral balances.

From the sources perspective we write:

GDP = C + I + G + (X – M)

which says that total national income (GDP) is the sum of total final consumption spending (C), total private investment (I), total government spending (G) and net exports (X – M).

From the uses perspective, national income (GDP) can be used for:

GDP = C + S + T

which says that GDP (income) ultimately comes back to households who consume (C), save (S) or pay taxes (T) with it once all the distributions are made.

Equating these two perspectives we get:

C + S + T = GDP = C + I + G + (X – M)

So after simplification (but obeying the equation) we get the sectoral balances view of the national accounts.

(I – S) + (G – T) + (X – M) = 0

That is the three balances have to sum to zero. The sectoral balances derived are:

- The private domestic balance (I – S) – positive if in deficit, negative if in surplus.

- The Budget Deficit (G – T) – negative if in surplus, positive if in deficit.

- The Current Account balance (X – M) – positive if in surplus, negative if in deficit.

These balances are usually expressed as a per cent of GDP but that doesn’t alter the accounting rules that they sum to zero, it just means the balance to GDP ratios sum to zero.

A simplification is to add (I – S) + (X – M) and call it the non-government sector. Then you get the basic result that the government balance equals exactly $-for-$ (absolutely or as a per cent of GDP) the non-government balance (the sum of the private domestic and external balances). This is also a basic rule derived from the national accounts and has to apply at all times.

The private domestic sector is only one part of the non-government sector – the other being the external sector.

Most countries currently run external deficits. This means that if the government sector is in surplus the private domestic sector has to be in deficit.

However, some countries have to run external surpluses if there is at least one country running an external deficit. That country can depending on the relative magnitudes of the external balance and private domestic balance, run a public surplus while maintaining strong economic growth. For example, Norway.

In this case an increasing desire to save by the private domestic sector in the face of fiscal drag coming from the budget surplus can be offset by a rising external surplus with growth unimpaired. So the decline in domestic spending is compensated for by a rise in net export income.

So if all governments (in all nations) are running public surpluses and some nations are running external deficits (the majority), public surpluses have to be associated (given the underlying behaviour that generates these aggregates) with private domestic deficits.

Even if the external sector balance was zero, the proposition would still be true. At least one private domestic sector would be unable to save overall.

These deficits can keep spending going for a time but the increasing indebtedness ultimately unwinds and households and firms (whoever is carrying the debt) start to reduce their spending growth to try to manage the debt exposure. The consequence is a widening spending gap which pushes the economy into recession and, ultimately, pushes the budget into deficit via the automatic stabilisers.

So you can sustain economic growth with a private domestic surplus and government surplus if the external surplus is large enough. So a growth strategy can still be consistent with a public surplus. Clearly not every country can adopt this strategy given that the external positions net out to zero themselves across all trading nations. So for every external surplus recorded there has to be equal deficits spread across other nations.

You might like to read these blogs for further information:

- Sad day for America

- Fiscal austerity – the newest fallacy of composition

- Stock-flow consistent macro models

- Barnaby, better to walk before we run

- Norway and sectoral balances

- The OECD is at it again!

Question 5: Premium Question

From the US National Accounts, you find that in 2006, the share of Personal consumption expenditure in real GDP was 69.9 per cent and by 2008 it had fallen to 69.8 per cent. Similarly, the share of Gross private domestic investment on real GDP was 17.2 per cent in 2006 and by 2008 had fallen to 14.9 per cent (and further to 11.8 per cent in 2009). The net export deficit over the same period (2006 to 2008) fell from -5.7 per cent of real GDP to -4.9 per cent in 2008. Finally, the share of Government consumption expenditures and gross investment in real GDP rose from 18.8 per cent in 2006 to 18.9 per cent in 2008 (and 19.7 per cent in 2009). These relative changes tell you that real GDP was lower in 2008 compared to 2006 because the increase in Government spending and the falling negative contribution of net exports were not sufficient to offset the declining contribution from consumption and investment.

The answer is False.

The detail in the question relates to expenditure shares in real GDP and clearly does not tell you anything about the growth in GDP. All that you are being told are that the shares are changing over the period 2006 to 2008 in favour of public spending.

The shares are given by the following equation:

where A(t) is the value of aggregate A in quarter under consideration (say Personal consumption expenditure) and GDP(t) is the value of GDP in the same quarter.

So a change in the public spending share from 18.8 per cent in 2006 to 18.9 per cent in 2008 just says that in 2008 the flow of public spending is a greater proportion of the flow of real output in 2008 than it was in 2006. The rising share could be associated with a declining, constant or growing real GDP.

The fact you know that over this time that real GDP growth in the US was falling is irrelevant – the question asks whether you can conclude from the information before you.

The other related measure is the contributions to GDP growth which tell you each quarter what the expenditure components contributed to the GDP growth in that quarter.

From the Australian National Accounts – December 2009 you can find the definition of the contributions to GDP growth which is represented by the following equation:

where A(t) is as before; A(t-1) – value of aggregate A in previous quarter; and GDP(t-1) – value of GDP in previous quarter.

The ABS indicate that “the contributions to growth of the components of GDP do not always add exactly to the growth in GDP. This can happen as a result of rounding and the lack of additivity of the chain volume estimates prior to the latest complete financial year.

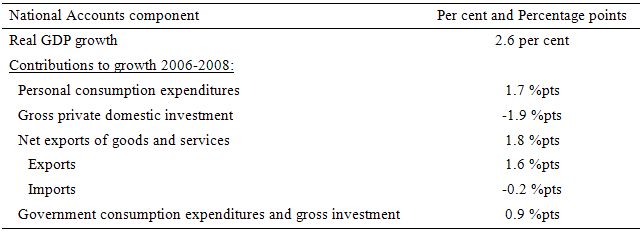

From the US National Accounts data you see that real GDP grew in 2005-06 by 2.7 per cent; then slowed to 2.1 per cent in 2006-07, 0.4 per cent in 2007-08 and plunged to -2.4 per cent in 2008-09. Over the period 2006-2008, real GDP grew overall by 2.6 per cent. The following table breaks down the contributions to that growth by the individual spending components (computed as per the Equation above).

The point of the question (if any) is to warn you into being careful to clarify the concepts being used before drawing conclusions. Too many people think they know what these terms mean and either mis-use them themselves to reach erroneous conclusions or allow themselves to be fooled by others who are touting erroneous conclusions.

If you are interested in more detail on national accounts then the 5216.0 – Australian National Accounts: Concepts, Sources and Methods, 2000 – is the place to go. Recommended reading if you want to get all the concepts and stock-flow relationships really sorted out. The system is universal and used by all statistical agencies.

i was wondering what Bill, what is your opinion of this idea that americans have been profligate for years ahnd spending well beyond there means. the evidence they often point to is increases in consumption as a share of gdp

Regarding the exchange rate question, if the Australian Dollar is rising more than that government desires, couldn’t the government just spend more money (“print” it) and thus cause the Australian dollar to weaken? I realize that per MMT putting more money in the economy isn’t inflationary as long as there was spare capacity in the economy, but would it weaken the Australian dollar against other currencies?

“Fourth, banks make loans to credit-worthy borrowers and these loans create deposits. If the commercial bank in question is unable to get the reserves necessary to meet the requirements from other sources (other banks) then the central bank has to provide them.”

Or, can the central bank either lower the reserve requirement or find some other way to lower the effective reserve requirement?

“But the process of gaining the necessary reserves is a separate and subsequent bank operation to the deposit creation (via the loan).”

Does it have to be subsequent? Are excess reserves “waiting” for a deposit to be created? That means the reserves were created before the deposit from the loan?

I have a question (not directly related to the quiz). More knowledgeable commenters – please correct me if I am getting anything wrong!

I was thinking about quantitative easing and “wealth effects.” One of the ways that quantitative easing could actually have a negative economic effect is that by buying longer term government bonds in QE, the Central Bank is actually decreasing the budget deficit by replacing interest bearing bonds non-interest bearing reserves, thus taking the money that would have been paid in bond interest out of the economic system. If the Central Bank theoretically decided to buy back ALL government bonds (which would be functionally the same as the government not issuing any bonds in the first place), then there would be no more interest payments as a part of the “national debt.” This would be fiscally contractionary, because interest payments on bonds are a significant portion of government expenditures (5% in the US). I began to wonder if maybe there was a way that monetary policy could actually work (at least theoretically) by doing the OPPOSITE and being fiscally expansionary.

So my question is this: what would happen if the Central Bank temporarily raised (short term or overnight) interest rates to an absurdly high level? What would happen if rather than LOWERING interest rates in the hope of spurring private sector lending (which as we know does not work in a balance sheet recession when there is a lack of demand for loans from creditworthy borrowers, and is furthermore rather irrelevant because loans create deposits, etc), the Central Bank took the opposite approach and raised interest rates to such an extent that the fiscal impact of the interest payment would overshadow the impact of stunting of whatever limited lending is going on at the moment in the private sector. While mainstream economics holds that raising interest rates “cools down” the economy, if the Central Bank were to raise rates high enough, could that actually do the opposite and stimulate the economy? What if, for a short 1 day period, the Central Bank raised interest rates for a 1 day deposit to 100%? Then all of the money that were deposited in the central bank for that one day would have doubled due to the massive interest payments. The Central Bank could raise interest rates as high as it thought was necessary in order to increase private sector net financial assets, and then could lower rates once again.

One problem I can see with this is that all of the interest would go to the banks which can actually deposit at the Central Bank. (That seems like quite a racket, huh?). This would basically be like a fiscal helicopter drop, wouldn’t it (albeit a drop straight into the lap of the banksters)? While it is not the best way to increase the budget deficit and stimulate the economy, isn’t that something that would help and that Central Banks have the power to do?

Maybe this is a crazy idea or wrong somehow, but I figure I can’t find out if I don’t ask!

“Regarding the exchange rate question, if the Australian Dollar is rising more than that government desires, couldn’t the government just spend more money (“print” it) and thus cause the Australian dollar to weaken?”

Yes, assuming that it buys (and holds!) financial assets denominated in foreign currency with its newly printed money. China has been practising an extreme case of this since before I was born, in maintaining a steeply discounted peg against the US$. And many countries defend “dirty floats,” in which the exchange rate is permitted to change, but only within a band around its present value (essentially limiting the rate of change to ensure that business has time to adapt to trends and to filter out some of the noise in the ForEx rate).

However, the currency (or currencies) you target can retaliate by doing the same to you. This causes inflation for both parties to the currency war, so if two countries both adopt neo-mercantilist ForEx policies targeting the other country, they will end up in a game of chicken and one of them will have to back down.

“Or, can the central bank either lower the reserve requirement”

Yes, but manipulating the reserve requirement is a cumbersome way to maintain a target rate, because the reserve requirements times the target rate is an overhead for the banks. So if you allow the reserve requirements to fluctuate, you’re making the banks’ overhead less predictable, for no perceptible gain. It’s far simpler and more transparent to let the rediscount rate change instead.

“or find some other way to lower the effective reserve requirement?”

Yes. The way to “lower the effective reserve requirement” without lowering the explicit reserve requirement is to permit the growth of a shadow banking system. That is to say, legalise organised counterfeiting. Legalising organised counterfeiting is usually considered A Very Bad Idea among those who have the best interests of the economy in mind and are even marginally smarter than a sack of hammers (Greenspan, Bernanke, Summers, Geithner, Rubin and Paulson are not included in this group of people, for either or both reasons…).

– Jake

Re JakeS’s “However, the currency (or currencies) you target can retaliate by doing the same to you. This causes inflation for both parties to the currency war, so if two countries both adopt neo-mercantilist ForEx policies targeting the other country, they will end up in a game of chicken and one of them will have to back down.”

Excuse a newby’s question, but I’m trying to get my head around these operations. As I understand it from Bill’s posts, inflation is the price rise which results from an excess of demand. I can also see how if your currency loses value versus another country’s, then the price of goods from that other country might be more expensive, i.e. inflationary. But other than the price of imports, dropping the value of one’s currency in the international exchange markets isn’t inflationary in and of itself, is it? So if two countries are targeting each others currency, their efforts could negate each other.

“But other than the price of imports, dropping the value of one’s currency in the international exchange markets isn’t inflationary in and of itself, is it? So if two countries are targeting each others currency, their efforts could negate each other.”

But it will push both of them down relative to the rest of the world. Which will mean that at some point one of them will pull out from the inflationary pressure of devaluing relative to countries that are selling them coal/oil/machine tools/pick your favourite structural import dependency.

The inflationary push from the cost of imports is simply not negligible. Not in general, and particularly not when you’re in a competitive devaluation scenario.

– Jake

“The inflationary push from the cost of imports is simply not negligible. Not in general, and particularly not when you’re in a competitive devaluation scenario.”

If this is so, then that might be a problem with the MMT advice to spend whatever it takes to reach full employment. I don’t remember Bill ever addressing it.

“So my question is this: what would happen if the Central Bank temporarily raised (short term or overnight) interest rates to an absurdly high level? What would happen if rather than LOWERING interest rates in the hope of spurring private sector lending (which as we know does not work in a balance sheet recession when there is a lack of demand for loans from creditworthy borrowers, and is furthermore rather irrelevant because loans create deposits, etc), the Central Bank took the opposite approach and raised interest rates to such an extent that the fiscal impact of the interest payment would overshadow the impact of stunting of whatever limited lending is going on at the moment in the private sector.”

There are three problems with this, and all relate to the purpose of intervening in a business depression in the first place:

The first problem is that this only helps the financial sector. Helping the financial sector is not the main point of intervening in a business depression; the main point of such intervention is to prevent the liquidation of your industrial plant (and, more to the point, the organisations, the know-how and the distribution chains that operate it). The way you do that is by making your industrial sector more valuable to its creditors alive than dead. You do that by giving it orders for work – that is, promising it money that it can pay to its creditors, but only as long as it is capable of carrying out useful work.

Think of it this way: A hedge fund has borrowed a lot of money on a very narrow margin, to launch a hostile takeover of a steel mill. Then the hedge fundies saddled the mill with most of the debt (as is standard practise – if things go sour, the hedge fundies slither out of the arrangement under cover of limited liability, because the target company is a separate accounting entity). Now the crash comes, and the steel mill is teetering on the brink of bankruptcy. Who’s losing here? The steel mill, obviously, is losing. The hedge fundies are losing. And the bank that lent to the hedge fundies is losing. Now, if you make the bank whole, the hedge fund and the steel mill still go belly-up. If you make the hedge fund whole, the steel mill goes belly-up, but the bank is also made whole. And if you make the steel mill whole (say by ordering a boatload of steel in order to expand your rail net), you not only make all three involved companies whole at the same time, you also gain some (hopefully) productive infrastructure.

Incidentally, this is why (aside from knee-jerk neoliberalism and plain mean-spiritedness) the financial sector usually hates effective intervention to stop an industrial depression: It moves relative wealth from the financial to the industrial and public sectors. In terms of absolute wealth, of course, the financial sector will be better off, because they will be made whole along with the industrial sector. But in *relative* terms – which is what matters for the financial sector’s *power* over the rest of society – they lose out.

The second problem is that many businesses have part of their debt in variable-rate arrangements, such as overdrafts. So unless you literally make it an overnight operation (which basically reduces it to a helicopter drop into the banks’ reserve accounts), you will cause an untenable debt burden for already struggling going concerns. This will lead to unnecessary liquidations of industrial going concerns – and the whole point of intervention is to protect your industrial sector from suffering under the FIRE-initiated liquidation spree.

The third problem is that it matters where you spend money during a balance sheet recession. Basically, the problem in a balance sheet recession is that there are no creditworthy borrowers. This means that as long as you are in a balance sheet recession, any money that finds its way into a bank will be taken out of circulation, either by being destroyed in paying down loans or by being left to rot in a reserve account with the central bank. So helicopter drops of money into the financial sector are going to have a very, very low multiplier effect on actual demand. See the example in point #1 for why spending farther away from the financial sector gives higher multiplier effects.

– Jake

“”The inflationary push from the cost of imports is simply not negligible. Not in general, and particularly not when you’re in a competitive devaluation scenario.”

If this is so, then that might be a problem with the MMT advice to spend whatever it takes to reach full employment. I don’t remember Bill ever addressing it.”

It might be a problem, but you’d have to get into some pretty contrived scenarios for it to matter very much.

Mobilising idle capacity in your economy is only inflationary to the extent that this formerly idle capacity uses its newfound remuneration to either a) do things that cause inflation in the domestic economy [The causes of domestic inflation are, AFAIK, not well understood. At least, I’ve never seen any particularly convincing mechanism presented for domestic inflation. Or rather, there are lots of possible mechanisms that sound plausible, but which provide no easy way to estimate their relative importance (or lack thereof).] or b) import goods, thus damaging your trade balance, and requiring you to devalue your currency, creating imported inflation in the process.

Now, inflation has three undesirable consequences: It damages your competitiveness, and thereby your balance of trade. It causes you to require more specie of whatever commodity you use to back your currency. And it reduces the value of money as a medium to store wealth.

The first can be fixed easily by devaluation (imported inflation is always, to zeroth order at least, less than the gain in competitiveness from devaluation, since imports make up less than 100 % of your economy – this ensures that the imported inflation will converge to a finite number when you iterate the process). And the second can be easily fixed by issuing fiat money, which does not require any specie in the first place. Which is why floating fiat currencies are such a nice invention: They sidestep the two most immediate undesirable consequences of inflation.

The final problem, that it debases the currency as a store of value, can be partly ameliorated by indexing wages, pensions and other currency-denominated non-financial sector cash flows to your chosen inflation index. But only partly, because you still have to keep inflation low enough that your typical economic actor will spend most of the money he receives before its value has noticeably degraded. In practise, if you want a quick and dirty rule of thumb, inflation seems to become uncomfortable for the real economy at around ten percent per year.

So the questions you want to ask yourself before launching a job guarantee are “how much of their new money are the recipients going to spend on imports?” and “how much inflation do we believe that their spending will cause domestically?” Once you’ve answered those two questions, you can compute whether the expected domestic inflation and imported inflation from the resulting chain of devaluations will put you over what you consider acceptable inflation. If your upper limit is in the 8-12 % per year range, the answer is most likely to be “no.”

As an aside, ten percent per year is *five times* the Bundesbank’s (I mean the ECB’s, no I mean the Bundesbank’s) target rate – which, by the way and incidentally to this discussion, it pulled completely out of its… thin air, let’s say. The treaties only say “price stability” – they don’t say “choke hold on the real economy,” they don’t say “2 %” and they certainly don’t mention pleasing the bond market god. Although they do mention that the ECB is not permitted to purchase member state debt on issuance, but is permitted to engage in open market operations. Which usually leads me to make sarcastic remarks on the purifying power of the bid-ask spreads of major international investment banks, which are apparently able to turn “sovereign debt” into “monetary instruments.” Yeah, I’m European and yeah, I’m bitter about Trichet, Weber and their buddies causing a constitutional crisis due to their ideological objection to proper, responsible economic governance.

Oh, and (moderate) inflation moves power from the financial sector to the productive economy. But that’s not a bug, that’s a feature.

– Jake