In my commissioned research activities, which are separate from the basic academic research that occupies…

RBA makes the wrong decision

Last month, the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) held its policy rate unchanged at 4.5 per cent contrary to what the bank economists expected. I said at the time in this blog – RBA confounds the market economists – but that’s easy – that RBA made the correct decision. It reflected the fact that the world economy is still in trouble as the fiscal austerity in various places starts to bite. It also reflected the fact that the trends in the local economy are far from clear and solid evidence is available to suggest that despite the boom in primary commodity prices (from Asia) our economy is still fragile. The labour market has considerable slack (12.5 per cent underutilisation rates) and housing and sales are flat or in decline. Most importantly (for the RBA) inflation is moderating in Australia. Nothing much has changed in the meantime and I was expecting (along with all my bank economist friends) for the RBA to hold its line again. Yesterday, the RBA confounded us all and pushed rates up by 25 basis points. But even more stark was the decision by the formerly public bank (privatised by the neo-liberals) – the CBA – to push its standard mortgage rate up by 45 basis points after announcing a huge and increasing profit earlier in the week. The RBA made the wrong decision yesterday.

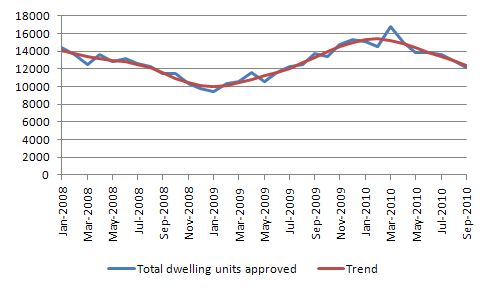

The day after the Reserve Bank of Australia hiked interest rates again, the Australian Bureau of Statistics released the latest data on – Building Approvals, Australia – for September. The trends in this data is one of the indicators we use to assess the heat of the housing construction market.

What is the story? Answer: Deteriorating!

The ABS report that:

The seasonally adjusted estimate for total dwellings approved fell 6.6% and has fallen for six months.

The seasonally adjusted estimate for private sector houses approved fell 2.2% and has fallen for four months.

The seasonally adjusted estimate for private sector other dwellings approved fell 15.7% following a rise in the previous month.

The seasonally adjusted estimate for the value of total building approved fell 3.2% in September. The seasonally adjusted estimate for the value of new residential building fell 5.4% and the value of residential alterations and additions rose 1.0%. The seasonally adjusted estimate for the value of non-residential building fell 0.7%.

The following graph (using the ABS data release today) shows you clearly which way this market is heading.

There is no hint of a building head of inflation steam heading from this source.

The ABC National News said this of the data:

Total dwelling approvals are now at their lowest level since June 2009 … The annualised pace of new dwelling construction dropped to 146,000 homes in September, well below the 200,000 homes many economists believe are needed annually to keep up with demand from a growing population … [they quoted a bank economist] … “the fall is a natural outcome of stimulus being withdrawn … The housing recovery in 2009/10 was entirely due to both monetary and fiscal policy being squarely aimed at this sector during the worst of the global financial crisis” …

First, the stimulus worked and was instrumental in providing some growth in dwellings to ease the shortage. Stifling that growth will add inflationary pressures! If you want output to keep pace with demand you have to stimulate capacity. Our central bank doesn’t seem to understand that as it goes in search of the future (sometime out there in the haze) inflation bogey.

Second, there is significant capacity potential that can be developed and real resources available to build it should demand rise. The economic growth that would follow would be non-inflationary. But the RBA seems to think that growth has to be curtailed now. More on that later.

In the light of today’s data release the Housing Industry Association declared war on the RBA saying that:

The weak housing outlook is compounded by yesterday’s interest rate hike by the Reserve Bank which, due to the additional independent 20 basis point increase by the Commonwealth Bank, will act like a sledgehammer on confidence and economic activity in the non-resource sectors.

This total 45 basis point increase in home-lending rates will seriously dent new home demand and confidence, and is worrying as it follows the removal of the First Home Owners Boost and the impact of previous rate hikes.

Expect to hear that message over and over as the unelected RBA continue to think they can “experiment” with the economy and apply their NAIRU-obsessed mentality on all sectors whether they are growing or not.

The RBA decision

Yesterday, the RBA surprised everyone (including me) and increased interest rates. In the formal statement from the RBA Governor announcing the decision to increase interest rates by 25 basis points we read that:

… The prices most important to Australia remain at very high levels, with the result that the terms of trade are at their highest since the early 1950s …

Public spending was prominent in driving aggregate demand for several quarters but this impact is now lessening. While there has been a degree of caution in private spending behaviour thus far, the rise in the terms of trade, which is now boosting national income very substantially, is likely to lead to stronger private spending over the next couple of years, especially in business investment.

… the moderation in inflation that has been under way for the past two years is probably now close to ending … Inflation is likely to rise over the next few years …

the economy is now subject to a large expansionary shock from the high terms of trade and has relatively modest amounts of spare capacity. Looking ahead, notwithstanding recent good results on inflation, the risk of inflation rising again over the medium term remains. At today’s meeting, the Board concluded that the balance of risks had shifted to the point where an early, modest tightening of monetary policy was prudent.

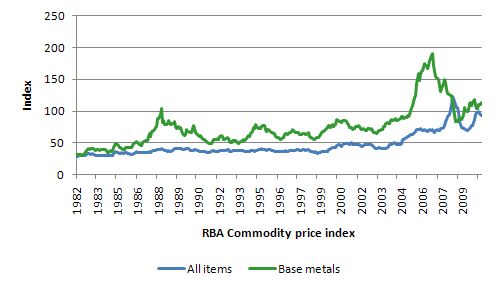

This is what they are worried about. The following graph shows quarterly movements in the RBA Index of Commodity Prices – G5 (since July 1982). It is clear that primary commodity prices are rising again and will probably get back up to where they were before the crisis hit as long as China keeps growing. Australia is a primary commodity exporter and thus enjoys these strong terms of trade.

The reality though is that the export sector remains a negative net contributor to overall national income. However, the RBA is signalling that they think the resources tied up in servicing the growing export market at present (principally in mining) will strain our capacity and inflation will be the result.

The Theory and the reality

Mainstream monetary theorists – the type that become central bankers or who the central bankers read – argue that inflation targeting provides the central bank with a framework or structure which allows it to promote understanding and dialogue with the public such that inflation expectations are purged and lower interest rates sustained.

They believe that inflation targeting eliminates inflationary biases in an economy because the central bank has a strong motive to maintain the policy stance.

They claim that it promotes transparency, accountability and credibility – the explicit announcement of price stability as the major focus of monetary policy makes it transparent and credible. The setting of known inflation targets places a discipline on monetary authorities to avoid so-called non-optimal policy shifts.

Credibility thus suggests that the public trust the central bank to maintain its nerve and act consistently to achieve price stability. Central bank credibility is considered by supporters of inflation targeting to a principle mechanism by which the economy purges inflationary expectations and risk premiums on interest rates

The problem is that the RBA’s behaviour now has become totally unpredictable.

They do have a formal inflation target and tell us more or less which data series they use to measure inflation.

So they say they desire to keep the annual inflation rate between 2 per cent and 3 per cent. They use two major indicators of inflation which are purged of outlier tendencies: a) “the 15 per cent trimmed mean (which trims away the 15 per cent of items with both the smallest and largest price changes)”; and (b) “the weighted median (which is the price change at the 50th percentile by weight of the distribution of price changes)”.

Please read this article – Measures of Underlying Inflation – for more information.

Further, please read last week’s blog (October 28th, 2010) – Not only smokeless, but looking rusty and unusable – which coincided with the ABS release of the latest inflation data for more information about these inflation measures and how the RBA claims they use them.

So you would think that if the desirable inflation measures were within the targeted band and falling (and related measures which feed into the inflation process) were benign or also falling then the RBA would conclude it should maintain a stable monetary policy stance. That would be the transparent and accountable behaviour.

But you would be wrong. In fact, they do not behave transparently at all. They achieve total opaqueness by defining the 2-3 per cent inflation target in terms of “future” inflation – a medium-term outlook. The trouble is that the medium-term is not specified in any sensible way. It is somewhere out there …

The conclusion you reach is that there is no precision in this process at all. They somehow have an in-built inflation bias that sees exploding prices everywhere even when all the current indicators are soft. Apparently we will experience strong investment in the coming 2 years and that will drive inflation up.

Why will it? Answer: apparently we are close to full capacity.

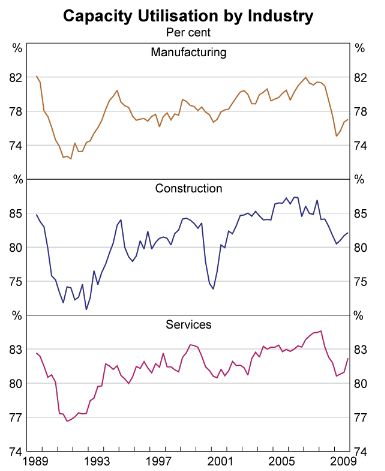

In its – February Monetary Policy Statement – the RBA produced this graph.

They concluded in relation to that graph that:

From around mid 2009, measures of capacity utilisation began to recover, and are now back above long-run average levels … these measures suggest that the economy starts the cyclical upswing with considerably less spare capacity than earlier thought likely.

If you believe that you would believe anything.

First, comparison with long-run averages conditioned by the data of the last two decades doesn’t tell us all that much because the government deliberately ran the economy at a below full-capacity level. They fell prey to the NAIRU concept (see below). The upshot was that we started to consider that the economy was “fully employed” when the reality was that there was huge volumes of labour resources lying idle for want of work.

So I don’t see that we are running out of capacity any time soon although I acknowledge that the relatively small mining sector might be growing fast at present.

Second, manufacturing remains in decline and will decline further in the coming months as a result of the appreciating exchange rate which is being exacerbated by the RBA pushing interest rates up further.

Third, construction is slowing as a result of the withdrawal of the fiscal stimulus. The major contribution of growth in construction in the last 18 months was the large public infrastructure projects. With housing and investment property approvals in trend decline (see data above) the outlook for construction is not strong at present.

Fourth, the services sector case is interesting. What capacity are we talking about in a largely labour intensive sector? Labour right!

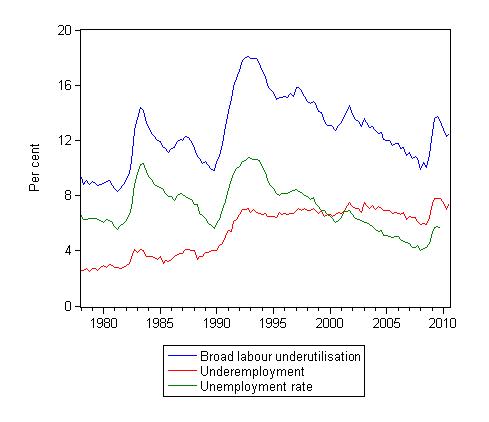

Well this graph is the latest from the latest ABS Labour Force data. The blue line is the ABS measure of broad labour underutilisation (the sum of underemployment and unemployment), the red line is the underemployment rate and the green line is the unemployment rate.

At present, the broad wastage of labour is 12.5 per cent with the underemployment rate being 7.4 per cent and the unemployment rate being the difference. Even at the height of the last boom the broad wastage was around 8.8 per cent.

These are conservative measures of the amount of labour that is being wasted because it excludes the hidden unemployed (who exited the labour force) and the other categories of marginal workers who could work if there were the right set of conditions.

But the 12.5 per cent represent idle work hours available from workers who are active, ready and willing. There is nothing marginal about that wastage.

It is often claimed that these workers (1.2 million odd) are not skilled enough to take the jobs that are emerging. This is the NAIRU nonsense that tries to claim that most unemployment is structural and therefore imposes an inflation constraint beyond which growth in nominal aggregate demand cannot be met with real output and employment increases.

Please read my blog – The dreaded NAIRU is still about! – to disabuse yourself of this sort of argument.

The NAIRU concept does not stack up theoretically or empirically. It is well established that changing labour market imbalances reflect cyclical adjustment processes which render any estimated macroequilibrium unemployment rate to be cyclically sensitive and therefore not the basis of an inflation constraint.

The NAIRU hypothesis suggests that any aggregate policy attempt to permanently reduce the unemployment rate below the current natural rate inevitably is futile and leads to ever-accelerating inflation. The vertical Phillips curve is accepted by most economists, monetarists and Keynesians alike.

However, the empirical world supports the notion that imbalances reverse when aggregate demand regains strength. The last thing we should be doing at present is to abandon job creation policies and start thinking that training programs and worker-attitude-correction strategies will produce any jobs.

Please read my blog – The structural mismatch propaganda is spreading … again! – for more discussion on this point.

I remind you of this insight from Michael Piore (1979: 10) which remains true today:

Presumably, there is an irreducible residual level of unemployment composed of people who don’t want to work, who are moving between jobs, or who are unqualified. If there is in fact some such residual level of unemployment, it is not one we have encountered in the United States. Never in the post war period has the government been unsuccessful when it has made a sustained effort to reduce unemployment. (emphasis in original) [Unemployment and Inflation, Institutionalist and Structuralist Views, M.E. Sharpe, Inc., White Plains]

But think about the service sector capacity. These jobs are mostly low-paid, low-skilled positions which require minimal training. So even if the 12.5 per cent of idle workers cannot drive a complicated piece of mining equipment (and I even would contest that claim) they can certainly flip a few burgers or whatever. So the claims about the service sector being close to exhausting its capacity have to be seen as ludicrous.

In this context, the central bank is captive to the following basic propositions which represent a “consensus” position among mainstream monetary economists (taken from Masson et al.(1997) ‘The Scope for Inflation Targeting in Developing Countries’, Working Paper 97/130, International Monetary Fund):

(1) An increase in the money supply is neutral in the medium to long run; i.e., a monetary expansion has lasting effects only on the price level, not on output or unemployment.

(2) Inflation is costly, either in terms of resource allocation (efficiency costs) or in terms of long-run output growth (breakdown of ‘superneutrality’), or both.

(3) Money is not neutral in the short run; i.e., monetary policy has important transitory effects on a number of real variables such as output and unemployment. There is, however, at best an imperfect understanding of the nature and/or size of these effects, of the horizon over which they manifest themselves and of the mechanisms through which monetary impulses are transmitted to the rest of the economy. And, a corollary of (3).

(4) Monetary policy affects the rate of inflation with lags of uncertain duration and with variable strength, which undermine the central bank’s ability to control inflation on a period-by-period basis.”

So in turn:

(1) They believe that monetary policy influences the money supply and it has no medium to long run on real output or employment. That is, the NAIRU nonsense. They deny that there are any lasting real effects of scorching aggregate demand.

Please read my blog – Inflation targeting spells bad fiscal policy – for more discussion on this point.

(2) They consider inflation to be more costly than persistent unemployment even though the latter costs economies millions of dollars of lost income every day and damages peoples lives irretrievably when the duration is long. There has never been credible evidence that modest inflation is costly.

(3) Monetary policy does suppress real output and employment in the short-run but they haven’t got a clue about these impacts – they do not know:

- The magnitude of the impacts.

- They do not know the duration.

- They have no idea of the path-dependencies involved – that is, the damage caused to potential growth rates by restricting capacity augmentation.

- They have no idea of how many bankruptcies they cause among households who are carrying record levels of debt;

- They have no idea of the impact on housing capacity development which as noted above is likely to be inflationary should they restrict supply when there is an obvious excess demand for low-cost housing in Australia at present.

- They do not really know how their policy changes work – through which channels.

(4) They do not have a clue of the relationship between interest rate changes and the inflation dynamics. This leads to risk averse behaviour where they act as they did yesterday – pushing rates up even though all the indicators are benign or falling – so it becomes a “just in case” approach – no precision – just guesswork.

The IMF paper quoted above says:

Inflation targeting in principle helps to redress this asymmetry by making inflation, not output or some other target variable, the explicit goal of monetary policy and by providing the central bank a forward-looking framework to undertake a pre-emptive tightening of policies before inflationary pressures become visible (emphasis in original).

The problem is that if aggregate demand is sensitive to their policy changes – and they surely believe it is – then they are deliberately damaging economic growth well before we are close to full capacity. They deliberately adopt a recession-biased approach where unemployment is seen as a policy tool rather than a policy target.

Given we cannot vote them out at any election – I find this intervention into our lives deplorable.

Inflation expectations

I have noted before – Inflation targeting spells bad fiscal policy – that the credible studies of inflation targetting which cut through all the mainstream ideology and confront the theory with the facts conclude that:

- On average, there is no evidence that inflation targeting improves performance as measured by the behaviour of inflation, output, or interest rates.

- Average inflation fell for non-targetters and targetters between the pre-targeting and targeting periods, but the targeters did not experience lower inflation rates.

The problem is that the rise of inflation-obsessed monetary policy coincided with the eschewal of discretionary fiscal policy and this imparted a recession-bias into the advanced economies. The stagnant nature of the European labour markets over the 1990s and beyond is a strong indicator of this sort of bias.

Even Franco Modigliani (who was one of the inventors of the term NAIRU) saw the light a bit later in life and pointed out in 2000:

Unemployment is primarily due to lack of aggregate demand. This is mainly the outcome of erroneous macroeconomic policies … [the decisions of Central Banks] … inspired by an obsessive fear of inflation … coupled with a benign neglect for unemployment … have resulted in systematically over tight monetary policy decisions, apparently based on an objectionable use of the so-called NAIRU approach. The contractive effects of these policies have been reinforced by common, very tight fiscal policies (emphasis in original) – ‘Europe’s Economic Problems’, Carpe Oeconomiam Papers in Economics, 3rd Monetary and Finance Lecture, Freiburg, April 6.

One of the other spurious claims made for inflation targeting is that central bank independence and the alleged credibility bonus that this brings should encourage faster adjustment of inflationary expectations to the policy announcements.

In terms of inflation expectations, the RBA continually claims that the inflation psychology has been expunged from the Australian economy as a result of their targetting regime. This is one of their consistent arguments that by acting ahead of any evidence of inflation they are keeping expectations of inflation at bay.

In the 1970s and 1980s this was a principle mainstream argument to justify using tighter monetary policy. The claim was the inflation has a life of its own even after the fundamental excess demand drivers are rendered benign. Allegedly, price setting agents (firms, trade unions etc) continue to make nominal demands based on their expectations of persistent inflation.

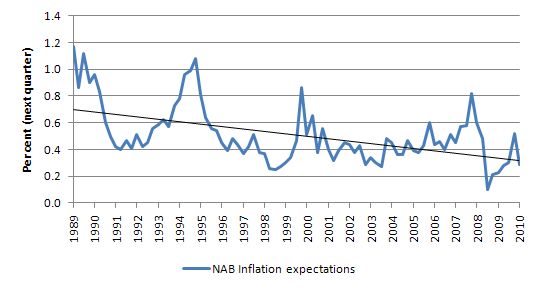

But if you consult the following graph it is hard to see any wave of inflationary expectation. At present the RBA definitely cannot be taken serious if they think we think inflation is just about to break out and so these expectations have to be expunged.

The following graph shows the NAB inflation expectations series which is derived from “the National Australia Bank Quarterly Business Survey respondents’ average expected increase in the price of final products in the next three months”. You can download this data from the RBA – Other Price Indicators – G4. The downward sloping black line is the simple linear regression (that is, the trend).

But what about their claim that inflation targetting did expunge inflationary expectations from the economy in the 1990s? As usual, the mainstream economics claim does not reflect the reality.

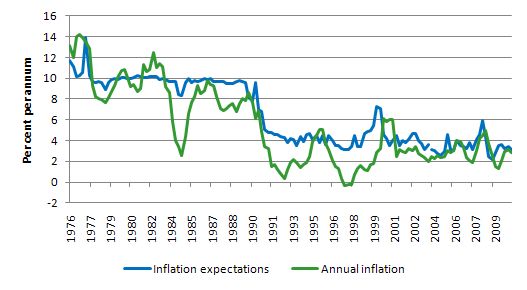

The next graph shows the median expected inflation rate for the year ahead (blue line) (from Melbourne Institute series) along with the annual inflation rate (green line) and the longer time span allows us to make some important observations.

First, inflationary expectations were not expunged by inflation targetting in Australia which began in 1994. The major recession of 1991 did the trick and had nothing to do with inflation targetting.

In fact, there were no inflationary pressures in the economy (GST period apart) after the 1991-2 recession. So it is hard to attribute the improved inflationary performance to the conduct of monetary policy at all.

Second, how does the mainstream explain the fact that the inflation expectations series (from Westpac/Melbourne Institute) which records price change sentiments in percent for a year ahead were consistently above the evolution of the actual inflation rate measured as the annualised change in the quarterly Consumer Price Index since inflation targetting was introduced?

If the inflationary expectations series is a valid indicator of underlying sentiment in the economy, then consumers are persistently erring in their forecasts, that is, failing to learn. How long does it take them to learn? What are the implications of this stupidity?

In a speech made in 2003, the RBA Governor – claimed that:

One reason for this is that there continues to be a significant proportion of households who anticipate inflation of 10 per cent or more even after a decade of inflation of 21/2 per cent. Presumably our message has yet to filter through completely.

It seems that the message still isn’t getting through completely.

Why this matters is because the underlying theory that the mainstream use (including central banks) is that households and individuals are rational, optimising decision-makers who have the capacity to form their expectations rationally. The Ricardian households are assumed to have perfect foresight. Many mainstream models that purport to inform the economic policy debate assume individuals have rational expectations – that is, they cannot be wrong consistently.

The reality – as is usually the case – tell us that these mainstream economic models are totally wrong.

Does the decision really matter?

As I note every time I discuss changes in interest rates I am always in two minds.

There are two important questions regarding the role of monetary policy. First, how sensitive is the real economy to interest rates movements? During recessions, monetary policy has little proven effects in activating an economy. In bad times lower interest rates do not induce consumer expenditure. And likewise, lower interest rates do not induce more investment (by making borrowing cheaper) as during these periods there tends to be excess capacity and output is not being sold.

Empirical evidence suggests that the interest elasticity of investment is at best low, non-linear, and asymmetric. While an increase in interest rates might moderately reduce investment during economic booms (when the economy is at or above capacity), the reverse is not true. In general, it is the outlook for profitability, rather than the price of credit, that influences investment.

For this reason, direct credit control is a more effective instrument of monetary policy than the interest rate. If monetary policy includes direct credit controls it may be reasonable to assume that there will be some effect on aggregate demand.

Further, the mainstream think that monetary policy changes are the appropriate vehicle for pricking asset price bubbles. What evidence do they have for that? Answer: no credible evidence. it is likely that if the central bank keeps increasing interest rates it will stop the bubble but at that point the central bank induces a collapse in the overall real economy.

For monetary policy to be “effective” it has to really damage the real economy in a significant way because it is such a non-targetted tool – it impacts broadly across the spending stream. It is far better to address specific sector price movements using fiscal policy which can zero in on the basics driving the bubble without damaging the rest of the economy.

The probable best conclusion is that monetary policy is mostly a very ineffective means of managing aggregate demand. It is subject to complex distributional impacts (for example, creditors and those on fixed incomes gain while debtors lose) which no-one is really sure about. It cannot be regionally targeted. It cannot be enriched with offsets to suit equity goals.

The regional issue is important. In cases like this, when, say a major city (for example, Sydney) is booming and housing prices are escalating, increasing interest rates impacts severely on the stagnant areas of the country.

In Australia at present the evidence is clear – mining is booming and the rest of the economy is moving along much more moderately. If the RBA policy changes are to be effective they would have to damage the weaker sectors as well as stifle the booming sector. The RBA claimed yesterday that:

The Board is also cognisant of differences in the degree of economic strength by industry and by region.

But they really have no idea of how their decision will impact on the weaker sectors and regions. And when they eventually ascertain the impact it will be too late.

This would not be the case using a well-targetted fiscal instrument – mostly in the form of specific taxation measures that can discriminate by region and demographic-income-property cohorts. You can never get that richness in policy design using monetary policy.

Further, if public housing is considered undesirable as a solution the federal government (with some constitutional reforms) could set up a fund to allow access to cheap mortgage instruments to low-income families and allow them to purchase housing (publicly- or privately-provided) with minimal distortion to the price distribution. MMT tells us that the federal government can always afford to do this.

Conversely, fiscal policy (when properly designed and implemented) is a much better vehicle for counter-stabilisation.

However, the impact of monetary policy also has to be considered in relation to the levels of debt that households are currently holding.

Australian households have record levels of debt and in the financial crisis lost a large slab of their nominal wealth. The RBA has always claimed that the debt was manageable because asset values were rising at a faster rate.

I always found the argument to be dubious given that a rising proportion of the “assets” being purchased with the increased debt were subject to significant private volatility (for example, margin loans to buy shares). But even more troublesome was the direct link between the debt-binge and the real estate booms which have pushed “investment” funds into unproductive areas at the expense of other areas of economic activity which would have generated more employment.

When the private sector is carrying very large debt burdens, the number of households and firms who are on the margins of insolvency increases.

Their capacity to make compositional changes to their expenditure to maintain their nominal contractual commitments declined dramatically in situations such as that.

At that point, interest rate rises can quickly accelerate the bankruptcy rates and lead to further real output falls.

This is especially important given our earlier point that the impacts of using monetary policy (interest rate variations) as the principle counter-stabilisation tool are unclear.

In the current situation, the RBA cannot know what the commercial banks are going to do. So when the RBA tightened by 25 basis points yesterday as an expression of where they wanted rates to sit they could not have known that the CBA (Commonwealth Bank) would immediately increase the standard mortgage rate by 0.45 basis points.

A 45 basis point rise given the oligopolistic (anti-competitive) nature of our big 4 banks is a significantly larger tightening of “monetary policy” than the RBA intended. That is, if the impacts are as the RBA predicts then there will be more real damage than their actual policy announcement would have estimated.

What sort of policy precision does this imply? How do they know that the overall impact won’t push the economy back into real decline? Answer: The RBA does not know and that is the problem of using monetary policy in this way.

Further, what is the impact of interest rates on inflation anyway? Increases in interest rates might be effective when inflation is caused by demand pressures. However, interest is a cost of doing business, and tends to be included in price. For this reason, raising interest rates will reduce inflation only if the effects on interest-sensitive spending (lowering aggregate demand) are greater than the effects on costs and prices. When inflation comes from the supply side, it is quite unlikely that higher interest rates will do anything to lower prices, indeed, they will probably add to supply-side induced inflation by raising costs.

Some believe that increases in interest rates allows a nation to avoid importing inflation due to currency depreciation. The down side is that higher interest rates may dampen investment prospects and the higher currency value may negatively affect exports. Likewise, higher interest rates will increase costs and thus induce higher prices. History is full of many examples of countries trying to use higher interest rates to protect the currency, only to find that the policy was impotent.

Raising interest rates by hundreds of basis points cannot compensate investors for losses due to large currency depreciations. Indeed, the higher rates can stoke a run out of the currency as currency speculators bet that the monetary policy will fail to stabilise the currency.

Further, it is clear that the RBA decision is exacerbating the exchange rate appreciation being driven by the rising commodity prices. The RBA’s decision will certainly damage the competitiveness of traded-goods industries that do not enjoy the bouyancy of demand conditions in world markets. So in the case of Australia this is manufacturing and agriculture.

The interest rate rises reinforce the impact on the exchange rate of the strong primary commodity prices. What will be the impact? Answer: The RBA does not know and that is the problem of using monetary policy in this way.

The bottom line is that this is all seat of the pants stuff at a time when there is no credible inflation threat. If the policy works as the RBA thinks then they are just damaging our change to eat into the huge pool of idle labour. They are damaging the chance to push closer to full employment. That is vandalism.

Conclusion

I could have embarked on a major bank bash today but decided against it. The behaviour of the CBA is appalling and I hope the Federal government is serious when it says it will legislate to make it much easier for consumers to shift banks and take their loans elsewhere. I recommend all existing customers of the big-four banks ring up the Newcastle Permanent Building Society and shift your accounts to them. It is a much more civilised institution.

Overall, yesterday’s RBA decision was a mis-use of its power.

Aside: the US Democrats get what they deserve

I note that the latest news tells us that the Republicans sweep Democrats from House in the mid-term elections in the US and that the manic Tea Party lot has become influential.

The soon to be speaker of the House, conservative John Boehner was quoted as saying:

Our new majority will be prepared to do things differently … It starts with cutting spending instead of increasing it, reducing the size of government instead of increasing it, and reforming the way Congress works. It’s clear tonight who the winners really are and that’s the American people.

I am sorry to disagree. The Democrats got what they deserved – they have been appalling given that two years ago they had a clean sweep to really do something good with America. But the American people are not the winners out of this.

Cutting public spending right now is the worst thing that the US government should do. Both sides of the English-speaking Atlantic are now headed in the same direction – back into the economic malaise.

The alleged 40 per cent of voters who claimed they supported the Tea Party tells me the US education system has failed.

So all my pals in the US – sorry! We have a spare room at our house. You know the address!

That is enough for today!

I was in Melbourne last week, walking around DFO. There are a helluva lot of imported goods at seriously discounted prices. If the RBA was not supporting the high AUD by increasing rates, surely the discounting trend would turn around and you would see higher prices on imported goods. At VW they had reasonable prices (and good fuel economy) the salesman was claiming a waiting list of several months. I didn’t check at Holden but I’m guessing it was next day delivery on most models. I’m interested to know if imported inflation factors into the bald one’s thoughts.

This is another straw on the back of the housing Camel. I can’t see the Camel holding out for much longer. Investors will be getting next months revised interest charges in the post soon. Even if they can reduce their losses through neg gearing, how much longer can they enjoy losing money with little prospect of capital gain?

Too boot! Deficit terrorising glove puppets in temporal ascendency in Europe and the US. Dedicated followers of fashion e.g. Ms Gillard and the ALP will soon be joining the chorus. Good old Oz might not be such a desirable refuge in 6 months time.

Hope you’ve got enough tinned food Bill….. for when the refugees come a knocking at your door.

BTW what was that thing about not forgetting to bring the Ashes?

Me being a Pom and all, I’m suspecting you might regret that bit of hubris. We have a few decent Yarpies on the payroll now ;).

Is it Aussie skittling time already. Doesn’t time fly!

Bill,

I know you’re not a blog-on-demand service, but perhaps you might find this statement, supposedly made by Commonwealth bank boss Ross McEwan……..

“Commonwealth Bank retail chief Ross McEwan said the bank no longer felt itself bound by Reserve Bank moves, telling ABC radio “the relationship with the Reserve Bank overnight cash rate over the last three years has just about – not quite but just about – become irrelevant”.

“The funding areas that we are getting our money from, they do not relate to the Reserve Bank overnight cash rate. That’s a position that we have not described well to our customers.”

……….startling enough to be worthy of a post?

Is he saying that big 4 will now ignore the RBA and simply do as they please?

Would anyone else care to comment on this apparent development?

“Is he saying that big 4 will now ignore the RBA and simply do as they please?”

You seem to be under the misapprehension that the central bank controls private bank’s interest rates.

It doesn’t. Competition for money determines private bank’s interest rates and they drive it down to the central bank rate if competition is sufficiently fierce.

Clearly there is insufficient competition in the banking market at the moment and a government listening to the real market signals would start capitalising new ones to force the existing banks into line, or out of business.

“they could not have known that the CBA (Commonwealth Bank) would immediately increase the standard mortgage rate by 0.45 basis points”

anybody … is that standard a variable floating rate?

If so, what’s the index and the typical spread?

The more I think about the (unpredictable) RBA, the more they leave me flat and confused. Mining may well have some capacity issues, but the rest of the economy doesn’t appear to. This results in the rather intriguing outcome whereby the RBA is effectively making the rest of the country tighten up in honour of our mining heroes. But to what end? Mining couldn’t care less about cash rates. There is enough profit in their products to begin with, and their borrowing terms at present are astronomically good (see Fortescue’s latest bond offering where investors simply cannot get enough). But if you look at demand indicators like Retail, Credit, and Buiilding Apps, it’s quite clear that there Is a general softening there. Take Credit growth….it’s not exactly booming, and yet, the RBA appear to think borrowers need to be taught a lesson! If the RBA continue down this road, I fear they are going to really regret it.

Dear Lefty (at 2010/11/03 at 21:35) and JKH (at 2010/11/03 at 22:04)

I was going to talk about that exact issue in today’s blog but I ran out of the time I allocate to write it and so I left it. I had produced the following graph which shows the spread between the RBAs policy rate and the standard variable mortgage rate since January 1996. You can see the spread has ballooned in recent years.

This relates to the CBA bosses comments. They claim that with more of their funding coming from abroad they are bound by the rates they have to pay in external wholesale markets than the cost of local funds which tend to follow RBA target rate movements. They say that that the cost of external borrowing has risen and that they are now duty bound to their shareholders to pass those costs on.

Three points:

(a) In the lead up to the crisis the costs of external funding in wholesale markets was very low (historically) and they did not pass that on in the form of a lower spread. All that has happened is that costs have moved back towards something that better reflects the risk and so we might call that a more normal situation;

(b) I could also have graphed their net profit performance over the same period and it has been rising dramatically with a dip last year given the crisis affecting bad debts. Westpac recorded an 81 per cent rise in their profit figure today, for example. Further executive remuneration continues to sky-rocket.

(c) The banks are also under pressure from the class action that is being fought out now which I predict they will lose. This is about gouging type behaviour and allegations of illegal charges. As a consequence, they are starting to relax some of these extra charges they impose on their customers and so they desire to make that up in more direct ways via an increasing spread.

We might start bank bashing if I continue. Bottom line: they are guaranteed by government to never fail. I would place caps on their profits as a symmetrical public act before nationalising them.

Hope that helps.

best wishes

bill

By the way, the RBA knew full well that banks would raise rates by more (for JKH’s benefit, by 20bps more than the RBA’s 25bps rise, making the standard var rate 7.81pc I think). How? Because each CEO has been screaming about it so loud, and so publicly, that the regulators are looking into the behaviour in terms of it being sneakily collusive. Nothing will come of any study/enquiry of course, but no-one, particularly the RBA, can be surprised. The CBa retail comments seem quite arrogant too. Why didn’t they raise them last month…..or thr month befor….or the one before that? Banks getting are getting away with selling the increase I funding costs by referencing the change from mid-07, also known as all-time tight levels in funding costs. A rolling 5yr average would tell a very different story I’d imagine.

Dear apj (at 2010/11/03 at 22:13)

You said:

That is the problem. They will not regret anything because they are unelected and ultimately unaccountable. They have every one fooled that they are independent and above the political system. If their policy choices harm the real economy then it will be the unemployed and those who lose their houses that will be regretting it.

best wishes

bill

Dear Andrew Wilkins (at 2010/11/03 at 19:12) and Neil Wilson (at 2010/11/03 at 21:25)

I will try my best to stop anybody talking about cricket – especially the one-day and 20-20 variety – on this blog. I might be fooling myself but I aim for a modicum of sophistication here! Games played by the colonialists and their minions are not very appealing. (–:

best wishes

bill

ps Australia is likely to be slaughtered anyway!

Thank you Neil. I do seem to vaugely remember Bill saying something to this effect in the early days of this blog. Time to re-read and refresh I guess.

apj, I wonder if mining really adds to the general spending stream to anywhere near the extent that the RBA seem concerned it does (or will do). Apparently we are experiencing an “expansionary shock” and the mining sector is” flooding Australia with some serious money “. Mining went almost belly up early last year but recovered very strongly on the back of China’s huge stimulus. It’s had plenty of time to hit us with the results of this expansion but like youself, I have noticed that demand indicators don’t appear to reflect any such thing occurring.

How much does mining really add to broad consumer demand? It’s a tiny employer, less than 2% of the total labour force. Mining workers may earn very high wages but they just don’t seem numerous enough to make a big impact on demand outside their local area.

Big iron ore, big coal, big alumina – these are extremely lucrative but how much of that lucre finds it’s way into the domestic spending stream? Much of this is claimed by foreign shareholders as far as I’m aware.

Then there’s mining investment, a goodly portion of which would have to be in gigantic mining machines (operated by a handfull of men rather than employing millions of men on picks and shovels). Can anyone show me the big manufacturing workshops in Victoria where all these capital goods are built from scratch? Or is it mostly imported? If it is, then this part of their investment leaks out of the economy without passing through very many hands.

I really do think that the claim of “mining is Australia’s golden goose” is fairly overblown.

Was the pre-GFC inflation derived from the booming mining sector or more from a boom in household credit growth that was occurring at the same time?

The RBA appear to believe that a roaring new boom – including a boom in private credit – is soon to take off. I am not convinced.

Thanks, Bill (Wednesday, November 3, 2010 at 22:25),

My anecdotal memory suggests Canadian banks may have been generally more robust in their competitive pricing behaviour on the same type of mortgage.

Canadian variable rate mortgages are indexed specifically against the prime rate, which itself floats against the CB bank rate. The index spread depends on cyclical margin considerations as well as borrower specific credit risk.

My recall is that there was extremely aggressive discounting of the variable rate mortgage spread for several years prior to the crisis, abrupt widening as the crisis developed, and now some partial retracement of the former discounting. My ineptness with actual data retrieval precludes more detail or verification.

It would be interesting to hear more on the class action suit in a future blog, if you are so inclined.

Yes, Republicans seize the House. Make gains in the Senate. But I always try to look on the bright side: in a thousand years we’ll all be dead, and then nobody will care anyway.

“The problem is that the RBA’s behaviour now has become totally unpredictable.

They do have a formal inflation target and tell us more or less which data series they use to measure inflation.”

If I may play devil’s advocate (as I know no one else would disagree with you on this topic), the RBA is not really unpredictable at all, just the month to month timing perhaps and in the big scheme of things this is not really important (except to those economists who think it is their jobs to make these predictions on the first week of every month). The RBA has been extremely clear that they want rates nudged up from these levels and another move to 5% is fully expected over the next quarter or so.

How exactly would you like the RBA to operate Bill? In reality underlying CPI has been around 3.2-3.5% in recent years so does that actually mean rates have been too easy? Did you actually read this or any of the periodical SOMP releases when you print your housing or underemployment charts? The RBA has said they cannot target every sector because MP is a blunt instrument however the tradeable sector is running the hottest it ever has and the associated risk to the economy outweighs that of the non-tradeable sector. They fully accept the economy is 2-speed.

I know you would like rates at 1% forever and could no doubt find a chart of underemployed people sitting on their bums at Bondi Beach to justify this but I think your anger is better directed at the Government who has cornered the RBA into this action. With the RBA mandate as it is, their decision on rates is straightforward.

These ridiculous double and triple first home buyer grants have been a major contributor to pushing property prices beyond the affordability of the average person and the continuation of negative gearing has institutionalised leveraged bahaviour in the minds of Australians. These are just two examples of ways the Govt could have acted in this or past cycles to indirectly help the RBA take pressure of MP. I could name a dozen more so I think your non-stop RBA bashing really is a bit unreasonable.

And how nice for self-funded retirees and those who might actually have a bob or 2 in the bank to receive a little pay increase compared to the rest of the world. Higher rates are universally condemned in the press but that clearly is not the entire picture.

bill says:

Wednesday, November 3, 2010 at 22:28

“That is the problem. They will not regret anything because they are unelected and ultimately unaccountable. They have every one fooled that they are independent and above the political system. If their policy choices harm the real economy then it will be the unemployed and those who lose their houses that will be regretting it.”

Conspiracy! LOL. The new neo-socialist RBA-terrorist.

Tell that to John Howard who got the boot because the RBA hiked during the election campaign.

There is much commentary and outrage in the press about the CBA (and banks in general) raising raes, but there is hardly any rational analysis. A couple of things that rarely get mentioned:

1) Most banks are also putting up their deposit rates. However they don’t put up deposit rates at the same time that they put up mortgage rates, they put them up as necessary in order to keep deposits in the bank. I think it’s fair to say that the spread between deposit rates and mortgage rates is probably as narrow as it has been in a very long time. But because mortgage holders outnumber deposit holders in Australia, any movement in rates and it’s effect on the entire nation is always portrayed in how it effects borrowers only.

2) Related to the above point, the overall net interest margin of the major banks has been narrowing. It is now probably around 2% to 2.5%. Is this reasonable or unreasonable? Any comments / outrage about bank profits that talk about $Xbn in profits is meaningless unless that figure is related to the amount of assets and /or equity in the bank.

Gamma says:

Thursday, November 4, 2010 at 4:15

“2) Related to the above point, the overall net interest margin of the major banks has been narrowing. It is now probably around 2% to 2.5%. Is this reasonable or unreasonable? Any comments / outrage about bank profits that talk about $Xbn in profits is meaningless unless that figure is related to the amount of assets and /or equity in the bank.”

An excellent point and one which guys like Bill and other senior academics like to point out when silly journos or ‘neo-liberal deficit-terrorists’ moan about the horrors of deficits and debt. It isn’t the absolute level of the profits that should be focused on but rather the ROE of the banks. A convenient switch-a-roo on their part.

My only gripe in this regard is with CEO’s Kelly and Norris who tearfully point out that ‘the cost of raising money on the international money markets has increased’ but are sneakily using 2006-2007 as reference which is a period of ridiculously tight bank MTN spreads vs USTs. If they used say the past decade’s average issuance spreads then they wouldn’t have much of an argument.

I wouldn’t attribute any of these CPI forecast divergences to stupidity — you are measuring two different things: expectations of future prices of a present fixed basket of goods that people would like to buy, when they expect to buy them, versus some increase in the total “consumption utiles” delivered per dollar spent.

People don’t look at a computer 10 times more powerful than the previous model, but which costs the same as the previous model, as being 10 times cheaper. Firms don’t view the next version of Microsoft Office as being twice as cheap even though it has twice the features for the same cost. Moreover, when there is a recession, and people substitute lower cost goods for higher cost goods, that does not mean they view prices as declining, even though CPI will decline somewhat because of this substitution.

If every year there is a holiday sale, and during the recession, the store cuts prices a bit more and sells a greater proportion of its inventory, then CPI will measure this as a greater price cut than people’s perceptions, because households don’t see quantities, they only see advertised prices – to them the product was a little cheaper “for one weekend”, but to the store, 30% of their gross sales were discounted by 1/3, whereas last year 10% were discounted by 1/4.

This does not mean that people have a psychological bias, but the CPI measure has a theoretical bias, in that it assumes that consumption is perfectly flexible — that if I buy a summer shirt in the winter, or go to an early bird dinner instead of when I would prefer to eat, or drive to an outlet mall instead of to my regular store — that none of this has a consumption cost. Therefore prices are falling, but I am “too stupid” to appreciate how much. I consistently underestimate how much prices have “really” fallen, and so we can through consumer choice and expectations out the window and just assume that people behave as automatons in our models.

RSJ,

“If every year there is a holiday sale, and during the recession, the store cuts prices a bit more and sells a greater proportion of its inventory, then CPI will measure this as a greater price cut than people’s perceptions”

“Moreover, when there is a recession, and people substitute lower cost goods for higher cost goods, that does not mean they view prices as declining, even though CPI will decline somewhat because of this substitution.”

I don’t know which CPI index you are referring to specifically, but neither of these comments is correct for the AUD CPI measure.

1) The CPI in Australia is a price index over a fixed basket of goods which is re-weighted every 5 years or so to reflect changes in consumption. So substitution will not effect the inflation measure within these 5 year intervals.

2) Price levels for particular goods are not determined as the average price paid for all stock sold. They are determined by observing quoted prices at regular intervals during the quarter.

In fact the AUD CPI attempts to measure exactly the same thing that you suggest the consumer inflation expectation is, namely changes in “prices of a present fixed basket of goods that people would like to buy, when they expect to buy them”. Granted, this might be different for other countries inflation indices.

In RBA Govenor Glen Stevens speech on the 25Th of October, during question time, he said it looked very similar to 2006 to 2007. I thought that made it obvious the rate would go up. In O6 and 07 Mining was stealing workers from lower profit businesses in our cities and towns who could not compete with the wage offered by the miners. Stevens thinks we are going back to that, listen to his answers to confirm this (link below). Stevens also said he believes that the transmission of money to the wider economy from the mining boom will be generally far reaching through the economy. So that is the excuse for pushing up rates, it punishes some parts of the economy but overall the transmission of money through the country will offset most of the bad. He mentions a figure of 150 Billion. On the third of May 2006 the RBA cash rate was 5.75 and by the 5Th of March 2008 it was 7.25! Stevens has only just started raising interest rates. it didnt bite last time until he got it up over 6.75% so he wont get the result he wants at the current 4.75%.

My view is Stevens thinks he got behind the game in 06 and 07 and he is determined to be in front of the demand for labour this time. It is a house of cards that depends on the price of one commodity, Iron Ore.

You can listen to the speech here http://boardroom-pc.streamguys.us/files/RBA/RBA20101025_GS/

(Sorry I dont know how to link it.) Listen to question and answers by Glen Stevens number 2, 3 and 5. Takes about 6 min.

I would probably agree with that Punchy – that’s what Stevens thinks.

But I maintain doubts about just how far and wide reaching the transmission of mining revenue is. As I said previously, mining employs only a tiny percentage of the workforce and when it is said that Australia is getting an excellent price for it’s minerals, I think it might be more accurate to say that well-heeled shareholders in places like New York, London and Zurich are getting an excellent price for Australia’s minerals.

The Queensland and Western Australian state governments may be raking in decent mining royalties but with their politically-motivated commitement to return their budgets to the biggest surpluses as soon as possible it’s obvious that they won’t be spending any great deal of that money.

I wonder if Stevens considers that the pre-GFC resource boom happened to coincide with a private credit boom and a great run up in house prices?

“I was going to talk about that exact issue in today’s blog but I ran out of the time I allocate to write it and so I left it. I had produced the following graph which shows the spread between the RBAs policy rate and the standard variable mortgage rate since January 1996. You can see the spread has ballooned in recent years.”

Thanks for the chart and the explanation Bill. Cheers.

I also don’t believe the economy is threatened by inflationary pressures from investment spending in the mining sector. If Glenn is truthful when he says he is trying to act premptively. We must assume the investments are commited but haven’t been made yet, so we don’t know for sure what the inflationary impact would be. I’m sure Bill will say no impact unless we actually get close to full capacity.

During 06 an 07 the housing market was ramping up and there was an associated increase in mortgage credit. Surely this was creating substantialy more inflationary pressure than mining investment. It was also helping to grow the Banks bottom line. The situation is very different different today when the Banks are struggling to increase their net mortgage lending. They are maintaining their bottom line by increasing the interest spread on mortgages.

The Banks signalled very clearly to Glen they wanted a rate rise so they could hang their excessive rate increases on the RBA’s rise. (Like nobody would notice!) I wouldn’t know what pressure was put on Glen in private, he made one public display of resistance at the 1st call then found a lame excuse on the 2nd calling. Rewards await the other side of the revolving door.

Here in Asia they are absolutely paranoid about QE2 creating hot money inflows, thereby creating asset bubbles. They are in a quandry, knowing interest rates will attract more foreign capital but still wanting to dampen domestic inflation. The inflationary concerns are around both asset inflation and CPI.

To echo one of Rays good points, Asian countries have all taken legislative steps to deflate their housing markets in reaction to dramatic currency inflows. Only this morning. Malaysia which is one of the least competent countries, announced 70% LVR requirements. Interestingly, the Asians are very happy their stock markets are being pumped, but recognise they will fall at the flick of a Goldman Sachs switch. They also believe Australia is the canary in the coal mine and are reacting strongly to every RBA move. Glenn is aware of this and is probably in the same camp. He has his hands tied by ineffectual Government leadership. He can’t use his blunt tool to differentiate between asset inflation and consumer price inflation.

There are also neo-liberal ideological beliefs that support the rate rises. In the neo-liberal paradigm, savings and profits are valued higher than labour. Glen is getting a good nights sleep with the thought he is rewarding the prudent and punishing the profligate.

There is still the issue of large consumer price increases should the AUD fall. In a macro economic long term sense I don’t know if this is significant. But with the large carry trade and hedge fund positions around the AUD, this would be a political hot potato were the AUD to reverse sharply. Sorry I lost a valid point with the cricket distraction, but I do want to understand this piece of the jigsaw in macro economic terms.

Dear Bill (just as an aside from the above discussion, and as I understand it),

Have been thinking about the broad civil aspects of human monetary systems: vis – our evolution through primitive tribal, slave, feudal and capital economies.

Even in the days of barter, there was a need for a dynamic medium of exchange (say conch shells), apportioned to the available goods and services. In later days, gold was used; but (as I understand it) problems arising from international trade and the same constraints that the conch shells faced persisted, and led to its abandonment. The US$ took its place, and today, the more pernicious aspects of its hegemony are being countered in proposals to mediate its power, through competition from the Euro, or a basketful of BRIIC? currencies. This could easily become an excuse for further conflict!

Again, as I understand it, all currencies of all sovereign countries that have not been pegged now float free, and are not tied to any physical commodity like gold or conch shells, or by proxy the $US. These currencies are fiat (let it be), exist in cyber space, and are represented by some physical token as a symbol of value (attributes: quantum, quality or meaning, purpose). In other words, over the course of human history, the medium of exchange has shifted from something physical – over which there was no absolute control or efficacy – to something that is in essence conceptual, and within human jurisprudence.

Pictorially, the door of the ancient cage of medium of exchange has been opened, but the little sovereign bird refuses to fly free – chained only by the skyways, its nature, and the natural world!

Many, I take it, don’t want this bird to fly free; nor hear its song! Some are afraid that free from its cage, it will turn into a monster and devour us all! But the door is already open, forever.

For the first time in human history, there appears (if I understand things correctly) the possibility – to not only stabilise the medium of exchange; but for the sovereign government of any country to gain sufficient control over its own economy, to be able to provide full employment to its population, and essential public services – given natural constraints. To put it in context: it’s a much ‘greater step forward for mankind’ than the nonsense uttered by Armstrong while collecting rocks on the moon. I wonder if we will take it?

In the same way, humans could create a separate dynamic medium of exchange for international trade, within human jurisprudence. And in gaining sufficient control over their national economies, help lay bare the excuses used in appropriating others.

I sincerely hope that 12 hours/day you spend in your little room can one day be eased Bill, and you get enough daylight and sun in accordance with the blueprint of the human organism! It’s the broad brush-strokes that interest me in your blog and in the comments. Cheers …

jrbarch

Gamma — It’s hard to not weigh by share of household expenditures or do hedonic adjustments in a price index. You have to do it as the goods basket is changing and product offerings are changing.

From that point on, it’s more a question of how aggressive or accurate the adjustments are made.

Resetting the weights every 5 years instead of every year actually makes the situation less accurate than if it was reset every year, and the statisticians know this, so they do a broad reset every 5 years but continuous resets as data comes out.

The process in AUS seems to be pretty much the same process as the BLS with benchmark years. Weights are assigned based on percent of household income spent on the purchase, and hedonic adjustments for quality, with adjustments made as soon as data is available.

So, even though the HES is every 5 years, it contains broad published categories like “autos”. But for the subcategories (e.g. premium cars vs. economy cars), then those would be revised based on sales volume or other purchase data as soon as is possible or practical.

I did some digging:

http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/0/B32B905A8A817531CA25705F001E57A7?opendocument

“The weighting pattern for the Australian CPI is based on the acquisitions concept and so the pricing of goods and services is also based on this conceptual approach for consistency …”

“…weighting practices vary at different levels of the CPI. At published levels, weights are reviewed about every five years. Typically these reviews follow the release of data from the Household Expenditure Survey (HES).At the unpublished levels the weights can be varied at any time. At the elementary aggregate or price sample level there is no explicit use of weights”

Regarding hedonic adjustments, you can see for yourself that pretty much every category is subject to a hedonic adjustment. For example:

“8.120 Audio and visual products are subject to frequent changes in styles and models. These changes quite often improve the quality of the products. Where the product currently priced for the CPI has been subject to such changes, an adjustment is made to ensure that the concept of pricing to ‘constant quality’ is maintained.

8.121 Computer products are likely to continue experiencing significant technological and quality improvements and conceptually, these changes will need to be reflected in the CPI prices. Since the ABS estimates are based on the US BLS computer indexes, no quality adjustments are made to the ABS price estimates as quality changes would have already been taken into consideration in the BLS indexes.”

Regarding Sales:

“8.60 ‘Sale’ or ‘special’ prices for clothing items are acceptable for the CPI provided:

the style name is available to be repurchased from the supplier

a full size and colour range is available

the ‘special’ requires no reciprocal commitment from the customer (e.g. to make a bulk purchase)

the promotional price applies for the full day on which the field officer visits.”

But note that clearance sales are not counted. I.e. if there is some residual inventory and there may not be enough for every shopper to buy, then it is not counted.

For autos:

“Quality adjustment

8.101 Whenever any specification change is made to a vehicle that affects its motoring performance, economy, comfort level, safety or durability (i.e. a change which affects the quality of the vehicle), an adjustment is made to the car’s reported price to allow for that portion of the price change that can be attributed to the quality change. In practice, these price adjustments are made at the time of the change or the new model release.”

jrbach

Nice post. The only people who favour giving the little fiat bird a fly around, are those who feel disenfranchised by the current system AND recognise the opportunity presented by a sovereign issuance of currency. Alas we free birders are few and far between. A few noble souls locked in dungeons tapping furiously away.

The lock ’em up brigade are the ones who seek to benefit from the current system OR fellow disenfranchised souls searching for a solution and arriving at the wrong answer.

As a realist, the odds are not looking good for free birders. The resources available to the jailors dwarf our paltry efforts. We do have the mighty sword of truth as our principal weapon so all is not lost. I dearly hope Bill continues. I guess he could shorten the blog and get out a bit more if he wants 😉

“During 06 an 07 the housing market was ramping up and there was an associated increase in mortgage credit. Surely this was creating substantialy more inflationary pressure than mining investment.”

Yes, exactly what I have long thought.

“The situation is very different different today when the Banks are struggling to increase their net mortgage lending. They are maintaining their bottom line by increasing the interest spread on mortgages.”

Now this is interesting to ponder where this might lead. Australian households are widely regarded as being the most (or among the most) over-leveraged in the world. Most of this is mortgage debt with average house prices somewhere from five to seven or eight times (depending on whose figures you believe) average household income. A combination of tax perks and incentives for housing investors – negative gearing, and in this case the ability to write off losses made on investment property against the investors total income, the halving of the capital gains tax some years later and then a series of first home buyer grants by the previous government and the current one have all gone into pumping up Australian house prices FAR beyond what I paid just over 10 years ago.

Australians appear to have reached a point where most of them have either no ability or no desire to take on any more debt relative to income. If the banks continue to jack up mortgage rates ahead of the RBA, how long before large numbers of over-extended borrowers can no longer meet their mortgage committments? I’m not suggesting that the banks would deliberately act in a suicidal manner but exactly where the “snapping point” might be is unlikely to be able to be seen clearly in advance.

Then again, many US banks extended large numbers of loans that they must have at least suspected could not be paid back, no doubt in the knowledge that if they got themselves in the shit, the government would run to their rescue.

Lefty,

Intuition tells me Australia will eventually endure a house price crash, just like the US and now the UK. From my starw polls, most Australians believe immigration, demand for minerals and investment in mining will be sufficient for the lucky country to muddle through.

I’m not so sure. Credit growth for housing has been a huge factor in the past 10 years economic growth and commodity prices have always proved fickle in the longer term.

Besides, if you can accept inputs from a Pom. I strongly believe Australia should set stricter guidelines for resource depletion, water use, agricultural land usage and population levels. It would be a shame if such a resource rich country ever became a net food importer. How long do you want the coal, iron ore and gas to last? 1,2, 3 or more generations?

Andrew Wilkins says:

Thursday, November 4, 2010 at 11:45

“The Banks signalled very clearly to Glen they wanted a rate rise so they could hang their excessive rate increases on the RBA’s rise. (Like nobody would notice!) I wouldn’t know what pressure was put on Glen in private, he made one public display of resistance at the 1st call then found a lame excuse on the 2nd calling. Rewards await the other side of the revolving door.”

AW, brother, as a crusty old banker of some insight I can absolutely assure you that the RBA does not do favours to the Banks and certainly does not give them an inside run as you have alluded to. If I had to guess I’d say the way the CEO’s were carrying on, that Stevens almost dared them to go independently in Oct so he would not have to. They didn’t so he did. Smart move by the Banks.

Funny how all the politicians are out slagging the Banks but they themselves deserve a certain part in it. Changing fiscal policy is very easy to do by the hand but difficult by the electorate. There is absolutely no political resolve to fix this issue easily as it would reverberate on what many say is ‘Australian’. (the right to negatively gear, get first home-buyer relief and maintain progressive stamp-duty scales).

RSJ, nice response. I accept your point that quality / hedonic adjustments are included in calculation of the CPI. In fact I didn’t actually dispute that in my original response. I agree that this could be a source of diversion of the calculated CPI and inflation expectations.

But the 2 points I made were that:

(1) SALE PRICES. Yes agree sales prices are taken into account, but not the sales volumes. Adjustments for the VOLUME of sales at reduced prices don’t occur therefore don’t skew the CPI downwards. Price samples are taken at various times throughout the quarter, so even if a large proportion of sales occur on a single day or week due to a sale, price samples are still taken at those other times when the product is not on sale and sales volume is lower. My understanding is that the price average is not scaled by volume of sales.

(2) PRODUCT SUBSTITUTION. As you have written, at the pubished levels, reweighting only occurs every 5 years. So if people switch from one (published) product to another this will not effect the calculation during this 5-year period. The classic example of this was in 2006 when a cyclone destroyed most of the banana crop in North Queensland. Banana prices went up massively (around 500%), and the recorded consumer price inflation was very high during that quarter. In reality, people just didn’t eat as many bananas (which obviously makes sense – a shortage was the cause of the price increase), they ate other fruit or something else. But the weighting of bananas was still fixed at the same amount, which is why the CPI print came in so high. At the unpublished level, I don’t know what re-weighting adjustments are made for substitution, but if it involved substituting a lower quality product, then I would imagine this would be taken into account, as per your previous points on quality adjustments.

So I don’t think that either sales (price reductions) or product substitution skews the calculation of the CPI lower than people’s general perception of what inflation is, to me it seems to be taken into account well.

Andrew,

I agree with everything you say there.

On housing, here is the latest ABS building approval data. It continues it’s downward plunge showing no signs of levelling out.

http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs%40.nsf/mf/8731.0

Combine this with house price growth for the September quater just gone – 0.1% and something looks potentially unpleasant to me.

Bill – this trend occurring as the BER stimulus is winding down does not seem to bode well for employment in the construction sector (among other ominous things).

Must dash – trivia night at the pub calls.

jbrach @ 12:21

Check out A. Mitchell Innes, “What is Money” (1913) for the debt theory of money. It’s in the mandatory readings over at Warren’s place.

http://moslereconomics.com/mandatory-readings/what-is-money/

TomH above:

Really interesting read – thanks Tom! So, it reminds me that ‘value’ cannot be represented by anything physical, because it is a dynamic quality in a human being. Therefore, its our values that need to change? Cheers …

jrbarch

Gamma,

Yes, you make a good point — you are right in that sales are mostly irrelevant, but you are still not going to get away from the substitution costs.

Think about it this way:

* Prices are sticky and we have monopolistic competition, which means people are willing to grant market power to firms. They are willing to “overpay” to get a certain type of good rather than switching to a different, competing good that has a lower cost. This is not “irrational”, because the household decides its own utility from consuming.

That means when they switch to a different good because they can no longer afford the good that they want to consume, they will not consider the lesser good to be “cheaper” but will obtain less utility per dollar spent because they were forced to make the switch. That is what I meant when I said that people determine price inflation by the types of goods that they are accustomed to buying when they are accustomed to buying them.

Now, you can argue that this type of subjective valuation is not the purview of a price index — except that it is! That is the whole point of hedonic adjustments — to measure the consumption “value” provided per dollar spent. But the current mechanisms of measuring that price index are based on some economic assumptions, namely perfect competition, so that consumption has zero substitution costs, whereas component increases in quality directly provide a consumption benefit.

And who is to say that households are not correct?

Middle class households used to have grand pianos in their living rooms and doctors used to make housecalls. Over time, these things became too expensive, and we substituted away to cheaper things. There is an ongoing process of substituting to cheaper things. But that does not mean that this substitution was costless from the point of view of the consumer. It is only costless if you assume perfect competition.

I think this is how we can get away with arguing that real GDP just keeps growing exponentially, even though resources are finite. I’m not saying that it’s not growing, but it may not be growing exponentially, when properly deflated. In the end GDP growth will be driven by the markup and will continue to grow exponentially independent of resource constraints, at least as long as we do not take substitution costs into account when determining the GDP deflator. The “ideal” consumption basket will always be drifting out of reach.

Not re-balancing the basket often works against you, because it means that the drift term gets larger before resets.

Who knows, maybe in the future, fresh fruit will be seen as a luxury that only the wealthy can afford, but I’m sure everyone will be buying some synthetic fruit equivalents that can be mass produced for a fraction of the cost, and yet households will still be complaining about rising prices when the CPI says otherwise. By “objective” measures, households will be getting more fibre or vitamins per dollar spent, but that does not mean that the price of consumption is decreasing. The hedonic adjustments are not really hedonic.

Now it makes sense that these types of life-style resets will be more intensive during recessions.

For example,

Suppose that prior to the recession, households that ate brand cereal were willing to pay a 10% premium to eat the brand cereal, and that 80% of the households did that, with 20% buying bulk cereal and seeing no value difference between the two.

Now assume that there are some income losses, and the price of brand cereal falls by 5%, and the price of premium cereal falls by 5%.

After the adjustment, only 50% of the households eat the brand cereal, and 50% eat the bulk cereal.