I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Counter-cyclical capital buffers

Recently (July 2010), the Bank of International Settlements released their latest working paper – Countercyclical capital buffers: exploring options – which discusses the concept of counter-cyclical capital buffers. This is in line with a growing awareness that prudential regulation has to be counter-cyclical given the destabilising pro-cyclical behaviour of the financial markets. Several readers have asked me to explain/comment on this proposal. Overall it is sensible to regulate private banks via the asset side of the balance sheet rather than the liabilities side. The countercyclical capital buffers proposal is consistent with this strategy and would overcome the destabilising impact of a reliance on minimum capital requirements that plagued the first two Basel regulatory frameworks. However, I would prefer a fully public banking system which can deliver financial stability and durable returns (social) with much less risk overall.

Background

Some of section and the next is based on a paper I wrote with Luke Reedman in 2002. Here is a link to the working paper version of the paper – Fiscal policy and financial fragility: why macroeconomic policy is failing.

What parades now as macroeconomic policy is a mishmash of half-truths and fallacy. At present governments around the world are being hectored by the IMF and other organisations into pursuing pro-cyclical austerity policy stances – which are an abuse of their fiscal policy capacity and responsibilities. In their latest latest paper on restoring growth in the Eurozone, the IMF model various public surplus debt profile scenarios.

The aim is to get public balances back into surplus as soon as possible, despite their being no sign that bank lending and private spending is picking up.

Unless a nation enjoys a strong trading environment, governments that pursue public surpluses are relying on the increased indebtness of the private sector to maintain economic growth. This strategy is unsustainable because private agents eventually increase saving to restore their balance sheets. Economic growth then falters, unemployment rises and the automatic stabilisers generate a public deficit.

To elaborate, we define involuntary unemployment as labour unable to find a buyer at the current money wage. In the absence of government spending, unemployment arises when the private sector, in aggregate, desires to spend less of the monetary unit of account than it earns. Nominal (or real) wage cuts per se do not clear the labour market, unless they somehow eliminate the private sector desire to net save and increase spending.

The non-government sector depends on government to provide funds for both its desired net savings and its tax obligations. The private sector cannot by itself ‘net save’ because saving is a signal to lend and so savers are always in an accounting sense matched by a borrower.

To obtain these funds, non-government agents offer real goods and services for sale in exchange for the needed currency units. This includes, of-course, offers of labor by the unemployed.

Thus, unemployment occurs when net government spending is too low to accommodate the need to pay taxes and the desire to net save. In general, deficit spending is necessary to ensure high levels of employment.

Persistent budget surpluses also force the private sector into increasing indebtedness. The sectoral balances (private, public and external) in the national accounts are:

(1) (S – I) = (G – T) + (X – M)

Equation (1) says that total private savings (S) is equal to private investment (I) plus the public deficit (spending, G minus taxes, T) plus net exports (exports (X) minus imports (M)), where net exports represent the net savings of non-residents.

Thus, when an external deficit (X – M < 0) and public surplus (G - T < 0) coincide, there must be a private deficit. While private spending can persist for a time under these conditions using the net savings of the external sector, the private sector becomes increasingly indebted in the process. So when the IMF is recommending a return to public surpluses they are really implying (though they do not say this) that private debt is better than public debt (given the stupid arrangements that governments have to issue debt when they net spend). Public surpluses just introduce fiscal drag (a draining of aggregate demand) to the economy. They do not provide a government with any 'saving" which can be used later to fund future public expenditure. It is a total neo-liberal myth that one budget position (a low deficit or surplus) provides a nation with more capacity to engage in a fiscal expansion that a higher deficit. To disabuse you of that myth, here is a quote from a paper I wrote with Warren Mosler in 2002:

Government spends by crediting a reserve account. That balance doesn’t ‘come from anywhere’, as, for example, gold coins would have had to come from somewhere. It is accounted for but that is a different issue. Likewise, payments to government reduce reserve balances. Those payments do not ‘go anywhere’ but are merely accounted for. In the USA situation, we find that when tax payments are made to the government in actual cash, the Federal Reserve generally burns the ‘money’. If it really needed the money per se surely it would not destroy it. A budget surplus exists only because private income or wealth is reduced.

In a recent FT article written by ECB boss Trichet, which was described in – this article – as exhibiting all the passion of a new religious convert” – Trichet “derides the previous economic panacea of boosting government spending to soften the economic downturn”. He said:

With the benefit of hindsight, we see how unfortunate was the oversimplified message of fiscal stimulus given to all industrial economies under the motto: “stimulate”, “activate”, “spend”! A large number fortunately had room for manoeuvre; others had little room; and some had no room at all and should have already started to consolidate … [there is] … little doubt that the need to implement a credible medium-term fiscal consolidation strategy is valid for all countries now.

The budget surplus may be applied to running down debt (that is, forcing the private sector to liquidate its wealth to get cash) but this strategy is finite. So budget surpluses destroy liquidity (debiting reserve accounts) which is deflationary. The weaker demand conditions force producers to reduce output and layoff workers with rapid increases in joblessness. Investment irreversibilities driven by uncertainty of future demand conditions then retard capacity growth and prolong the downturn.

So the austerity measures are really setting the world up for the next crisis. At the best of times, for economic growth to occur, the pursuit of public surpluses necessitates an increase in the net flow of credit to the private sector and increasing private debt to income ratios.

At some point a threshold is reached where the private sector, by circumstance or choice, becomes unwilling to maintain these deficits? For this reason, the reliance on rising indebtednesses to underwrite private spending is ultimately, an unsustainable growth strategy.

The private sector (and the spending the debt has supported) becomes increasingly vulnerable to interest rate increases, declining asset values and lost incomes.

This insight is at the heart of Minsky’s Financial Fragility Hypothesis and has implications for the latest offering from the Bank of International Settlements on countercyclical capital buffers as a preventative measure to offset future financial crises.

Of-course, with bank credit so weak at present, the austerity measures being implemented will more than likely stifle growth much earlier than would be the case if the private sector was embarking on a new wave of borrowing.

Minksy Financial Fragility hypothesis

Two questions are raised by the aggregate demand structure above. First, what motivates and enables the private sector to run deficits over extended periods? Second, how long can this process continue? Minsky’s Financial Fragility hypothesis provides insight into these two questions.

The type of economic system envisaged by Minsky is a modern capitalist system consisting of long-lived, expensive, and privately owned capital assets with sophisticated financial arrangements (debt contracts) designed to fund the acquisition of such assets.

For Minsky, it is the processes and consequences of the investment in such capital assets in a modern capitalist system that forms the theoretical crux of the Financial Fragility hypothesis.

The Financial Fragility hypothesis has two fundamental propositions noted in the introduction:

- First, the economy has financing regimes under which it is stable and financing regimes under which it is unstable.

- Second, expansions driven by private spending are typified by agents taking increasingly fragile investment positions.

Debt-holders, meet their repayment obligations using cash flow derived from the investor’s operations and/or fulfillment of owned contracts (both income cash flows); the sale of capital or financial assets (portfolio cash flows); and/or the issuance of debt (balance sheet cash flows).

The articulation between expected income cash flows and contractual obligations are what Minsky terms ‘financial relations’ with three categories being identified:

- An investor is hedge financing if realised and expected income cash flows are sufficient to meet all their payment commitments.

- An investor is engaged in speculative financing if their balance sheet cash flows exceed expected income receipts and they roll-over existing debt.

- An investor becomes a Ponzi financial unit if they increase debt to meet the gap between their balance sheet cash flows and expected income receipts. So unlike hedge units, speculative and Ponzi financing units must engage in portfolio transactions to fulfill their payment commitments.

While the Financial Fragility hypothesis focuses on business enterprises, similar ‘financial relations’ apply to households. The debt financing of owner-occupied or investment housing also requires households to meet contractual payments from income, portfolio, and balance sheet cash flows.

It is the relative weight of income, balance sheet, and portfolio payments in an economy that determines the vulnerability of the financial system to disruption. An economy in which income cash flows are dominant in meeting payment commitments is relatively immune to financial crises whereas an economy is potentially financially fragile and crisis-prone if portfolio transactions are relied on for meeting payments.

Over a period of prolonged prosperity, the economy endogenously transits from stable financial relations (an aggregate liability structure dominated by hedge finance) to unstable financial relations (an aggregate liability structure dominated by speculative and Ponzi finance). This dialectic is exacerbated by the pursuit of public surpluses.

To understand the hypothesised dynamics, we begin in the aftermath of a recession where all investing units (hedge, speculative and Ponzi) re-evaluate their safety margins. Units that encountered stress in meeting debt obligations inflate their safety margins, even though they remained solvent during the downturn.

This process is referred to as ‘balance sheet restructuring’ or ‘reliquification’. A typical expansion begins with a public deficit providing a floor under income cash flows and loose monetary policy allowing investors to validate the pre-existing debt structure.

Simultaneously, government debt is fed into the portfolios of banks and other financial institutions, decreasing the exposure of the banking and financial systems to default. This combined with the balance sheet restructuring allows the economy to emerge from crisis with a more ‘robust’ financial structure than it had when the crisis took place.

This process has been proceeding over the last year and a half as governments implemented their fiscal stimulus programs. The austerity push will prematurely terminate this process – premature in the sense that the process of balance sheet restructuring within the private sector is far from complete. There is no thirst for private debt at present and banks are definitely not feeding a credit expansion. The latest IMF paper provides strong evidence for the last point.

So there is every danger that the world economy will dip back into recession under the demand-draining pressure of the fiscal drag.

According to Minsky, if the economy does not dip back into recession, the recovery then gives way to a period of economic tranquility where the cash flow, capital value and balance sheet characteristics of borrowers and lenders continue to improve. As this period endures, investing units observe that realised quasi-rents on capital assets begin to exceed expectations.

In hindsight, it appears that safety margins incorporated into liability structures were too pessimistic as the effective demand for the goods and services of businesses exceeds ex ante aggregate supply. In the short run, firms accommodate the excess through higher capacity utilisation rates. But eventually investment rises and begins to draw on external debt and equity funds.

For a unit to increase its liabilities there must be corresponding lender. The Financial Fragility hypothesis asserts that bankers live in the same climate of expectation as the managers of capital assets. The increase in debt-financed investment depends not only on the expectations of investors, but also on the willingness of bankers to ratify, if not drive the leveraging.

Borrowers previously considered too risky now become acceptable risks. The same pattern emerges in the liability structures of financial intermediaries. Debt levels rise as views about an ‘appropriate’ liability structure change. The heightened expectations breed a disregard for the possibility of failure the expectations of a normal business cycle are replaced by the expectation of steady economic growth.

This change of state, called the economics of euphoria by Minsky, is characterised by the development of significant imbalances in credit and asset markets.

The strong economic growth is driven by large private deficits generated by excessive investment in capital assets and household items based on unrealistic expectations of income cash flows and freely available credit. Such periods are also accompanied by growing public surpluses through the operation of the automatic stabilisers and/or explicit spending cutbacks.

Through phases of recession, recovery, tranquility, and euphoria, the economy endogenously moves from robust to fragile financial structures. The fragile structure characterised by high levels of speculative and Ponzi finance becomes vulnerable to a multitude of shocks, any of which, in isolation or concert, can alter perceptions of future income flows needed to validate the debt structure and drive the economy into crisis.

Prudential regulation in a Minsky world

The latest financial crisis has shown categorically that financial markets operate in a pro-cyclical manner which is consistent with Minsky’s insights. So in strong economic times, there is excessive risk-taking and then the opposite occurs after a recession.

While the financial market players like to present themselves as being important, in fact they a followers – and operate in herds and this drives the de-stabilising pro-cyclical behaviour.

At present, the banks are behaving very conservatively because they have been making larger provisions for bad debt which has impinged on their capital buffers. This conservatism is now impeding growth and so fiscal policy is required to sustain any semblances of a recovery. The austerity programs fail to acknowledge this fact.

Some commentators are pointing out that the surprise UK GDP growth figures are a sign that austerity is not damaging. That assessment is far-fetched. What the last week’s national account result from the UK tells us is that there was sufficient fiscal stimulus added to aggregate demand to get the economy moving again. The austerity impacts are yet to come. They will be damaging.

The fact that financial markets operate in a pro-cyclical manner means that financial regulation should lean against the wind – that is, provide counter-cyclical capacity to the economy. In this way, the need for significant fiscal responses is reduced.

We have known about this for years but governments failed to introduce adequate regulatory environments. They were being constantly pressured by the neo-liberals to break down regulation because the financial market players knew that, in general, they could pocket the upside returns (made larger by excessive risk-taking) and socialise the downside losses (for example, all the recent bailouts).

BIS counter-cyclical capital buffers

In December 2009, the Bank of International Settlements put out two discussion papers – Strengthening the resilience of the banking sector – consultative document – which outlined “a package of proposals to strengthen global capital and liquidity regulations with the goal of promoting a more resilient banking sector” and – International framework for liquidity risk measurement, standards and monitoring – consultative document – which outlined “a package of proposals to strengthen global capital and liquidity regulations with the goal of promoting a more resilient banking sector.”

The BIS said that:

The objective of the Basel Committee’s reform package is to improve the banking sector’s ability to absorb shocks arising from financial and economic stress, whatever the source, thus reducing the risk of spillover from the financial sector to the real economy.

These proposals will form part of the yet-unofficial Basel III accord. The key features will be more strict definitions of Tier 1 capital. Please read the blog – Bond markets require larger budget deficits – for more detail on that.

Further, the BIS are proposing to introduce a leverage ratio which will curtail excessive banking leverage and also supplement the risk-based assessment frameworks used by banks.

Another major change is the proposal to introduce a framework of counter-cyclical capital buffers. This framework will help attenuate the excessive cyclicality of the minimum capital requirement and conserve capital in good times.

The aim is to curb the pro-cyclical behaviour of the financial markets and to protect the banking system from excess credit growth.

Recently (July 2010), the BIS released their latest paper – Countercyclical capital buffers: exploring options – which discusses the concept of counter-cyclical capital buffers. This is in line with a growing awareness that prudential regulation has to be counter-cyclical.

As background, in this blog – Bond markets require larger budget deficits – I outlined the system of banking supervision based on capital adequacy requirements which has been developed by the Bank of International Settlements.

The idea of countercyclical capital buffers is simple. They aim to protect the banking system from future potential losses. The BIS say in their latest working paper that:

The proximate objective of countercyclical capital standards is to encourage banks to build up buffers in good times that can be drawn down in bad ones. Buffers should not be understood as the prudential minimum capital requirement. Instead, they are unencumbered capital in excess of that minimum, so that capital is available to absorb losses in bad times. Countercyclical capital buffer schemes can be thought of as having two closely related ultimate objectives … One is to limit the risk of large-scale strains in the banking system by strengthening its resilience against shocks. The second is to limit the banking system amplifying economic fluctuations. In most circumstances, the difference between the objectives is not significant. For example, it is precisely when the financial system experiences large losses that its impact on the macroeconomy is strongest, through the induced credit contraction and asset fire sales. However, the relative weight assigned to the two objectives can colour the assessment of various schemes. For instance, a policy maker with a focus on the first objective may be less tolerant of reductions in capital buffers in bad times even if this helps to sustain overall lending.

So by forcing banks to build up capital during growth periods, the proposal reduces the chance (and size) of a credit explosion. The banks would also not have to raise capital in bad times just when it is most difficult to do so (the so-called paradox of capital).

This proposal is a so-called “third layer” of protection. The BIS envisage a model that has the following features.

Layer 1 is the minimum capital requirement faced by all banks and expressed as some percentage of “risk-weighted assets”. Failing this requirement would trigger an “operational intervention” – assets sales, forced capital raising or amalgamation with a competitor.

Layer 2 is the “conservation buffer” which would be some extra percentage above the minimum capital expressed in terms of risk-weighted assets. Falling below this buffer (but remainging above Layer 1) would place restrictions on the bank’s capacity to distribute its earnings.

Layer 3 is the market-specific “counter-cyclical buffer” above the conservation buffer. It only becomes binding during a period of “excess aggregate credit growth” that is “associated with a build-up of system-wide risk”. The BIS claim this might happen every 20 years years.

The BIS working paper discusses two approaches to determining the counter-cyclical buffer. They say:

A major distinction for countercyclical capital schemes is whether conditioning variables are bank-specific (bottom-up) or system-wide (top-down). The evidence … indicates that the idiosyncratic component can be sizeable when a bottom-up approach is employed. This would imply large differences in the values of the adjustment factors across banks, even in times when broad financial stability pressures build up. In addition, the persistence of bank-specific factors can be very low, so that the volatility in the target for the countercyclical capital buffer could be substantial, sometimes changing size and direction considerably in several successive periods.

For a top-down approach, the analysis shows that the best variables, which could be used as signals for the pace and size of the accumulation of the buffers, are not necessarily the best signalling the timing and intensity of the release. Credit seems to be preferable for the build-up phase. In particular when measured by the deviation of the credit-to-GDP ratio from its trend, it has proven leading indicator properties for financial distress.

So they suggest a “market-based” rather than a “bank-based” system.

The challenge in designing this sort of scheme which would work more or less like an “automatic stabiliser” is that the minimum capital requirement against which the buffer would be calculated is itself cyclical.

The paradox of capital relates to the way in which the minimum capital requirements actually work to undermine the stability of the financial system (this is the so-called paradox of capital). In bad times, as the Minsky ponzi phase is unwinding, the banks have to write-down their poor assets which reduces capital. If a bank drops below the minimum capital requirement they have to raise new capital (or sell assets) just when it is most difficult to do so. The risk of failure is then magnified.

So the countercyclical capital buffers are meant to address this weakness in the minimum capital rules. So when there is a crisis and the banks are writing-down bad assets, the capital buffers are diminished rather and this reduces the risk of driving the bank below the minimum.

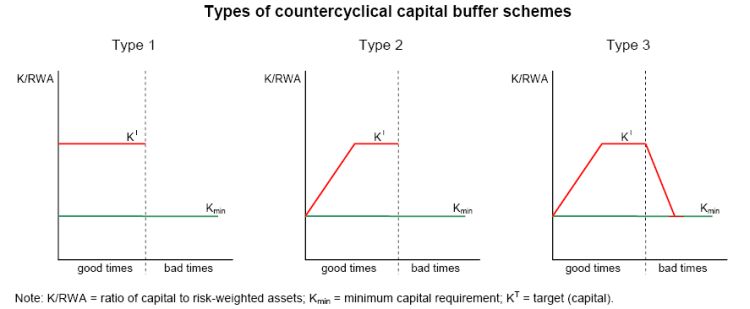

The following graph is taken from the BIS Graph II.1 and shows the different types of counter-cyclical buffer schemes that are possible.

First, in the left-panel, in good times the banks would face a fixed percentage above the minimum but no requirement in bad times other than the minimum.

Second, in the centre-panel, requires “an increasing target in good times, possibly until it reaches some upper limit”. The “build-up could be related to some conditioning variable (eg credit, earnings, a credit spread).

Third, release from the requirement “could either be instantaneous once bad times arrive (see Graph II.1, middle panel) or gradual, if it is linked to the same or another conditioning variable (see Graph II.1, right-hand panel).”

At this stage of the discussion phase, the BIS has offered very little specific information about the calibration of the buffers. How big will they be and what size is best?

The new developments are an improvement on Basel I and Basel II. Basel I was not very effective for many reasons, including:

- There was only a partial differentiation of credit risk across the 4 asset categories.

- The 8 per cent capital ratio was static and didn’t reflect changing market circumstances (rising risk).

- There was zero recognition of the term-structure of credit risk – that is, they did not incorporate the “maturity of a credit exposure”.

- They did not properly recognise portfolio diversification effects.

There were other problems and this led to the 2007 Basel II Capital Accord. You can read all the changes introduced by Basel II HERE. Essentially it added “operational risk” (losses arising from human error or management failure) and defines new ways of calculating credit risk. New approaches to assessing these risk exposures were recommended.

The problem with the Basel framework is that it gave banks an incentive to underestimate credit risk. The banks are allowed under the framework to use their own models of risk assessment to reduce the required capital and increase returns. Part of those returns are the fabulously large bonuses that are now common in private banking. It is clear the managers failed to allocate adequate capital as the risk exposure of their banks was increasing rapidly in the lead up to the crisis. It is clear that a system of self-regulation and the ability to under report risk failed.

So now there is a recognition that the minimum capital requirements are inadequate and can destabilise the financial system.

The obvious way a bank which is sitting on its requirement capital ratio can expand its capacity to lend is to increase its capital – which is exactly what the framework is designed to induce.

This raises the obvious tension that exists between the banks and the regulators. The former complain that any limitations on their leverage ratios reduces their profitability. Yes – which is exactly the intention.

Earlier this year (March 29, 2010), Andrew Sorkin in his New York Times column last week entitled – The Issue of Liquidity Bubbles Up – was arguing that any move to increase capital requirements for banks in the US would stifle economic prosperity. He quotes the now totally discredited Alan Greenspan:

A bank, or any financial intermediary, requires significant leverage to be competitive … Without adequate leverage, markets do not provide a rate of return on financial assets high enough to attract capital to that activity. Yet at too great a degree of leverage, bank solvency is at risk.

While this is correct, it makes a good (unintentional) case for public banking. Over what period do we compute the rate of return? What do we include in this calculation?

If we were to include the massive losses and public bailouts that were required to prevent the entire world financial system from collapsing then the risk-weighted returns would be negative by a long way. A public banking system can deliver financial stability and durable returns (social) with much less risk overall.

Conclusion

But overall, it is sensible to regulate private banks via the asset side of the balance sheet and that is the strategy employed by the capital requirements framework. It is also clear that higher capital requirements and more attention to “off-balance” sheet activity is now necessary.

In a system where the capital requirements are too low, the public exposure to bank failure is that much higher and the moral hazards are high. While the best option is to nationalise the banking system and make it 100 per cent focused on public purpose, the more realistic case is to ensure private banks have adequate buffers to insulate the system against panic.

That will reduce profitability (narrowly defined) but enhance social returns.

The other angle is that private investors would probably accept lower returns if there were tighter capital requirements because their risk exposure is lower. However, total costs to the sector rise when capital requirements rise.

In these blogs – Operational design arising from modern monetary theory and Asset bubbles and the conduct of banks – I outlined how I would reduce the role of banks which would make them much easier to regulate.

That is enough for today!

Bill –

I’m a bit concerned about one of your assumptions:

Unless a nation enjoys a strong trading environment, governments that pursue public surpluses are relying on the increased indebtness of the private sector to maintain economic growth. This strategy is unsustainable because private agents eventually increase saving to restore their balance sheets. Economic growth then falters, unemployment rises and the automatic stabilisers generate a public deficit.

How often does that ever happen?

I know the private sector are sometimes pushed into restoring their balance sheets by the threat of rising interest rates, but that’s the result of government policy, not a desire to save. I’m struggling to think of a single example of faltering economic growth being a spontaneous result of decreasing private debt – 21st century Japan’s the only possible example that comes to mind, but it does enjoy a strong trading environment.

Here is a simpler solution: stop banks making loans. That is, we have two types of organisation: first, banks, which take deposits and transfer money when asked to do so.

Second all other entities and organisations (including individual people). This second group IS allowed to lend. The result would be an end to commercial bank created money (which is pro-cyclical, and which is the root of the problem). And as to the idea that would would reduce the total stock of money, which in turn might be deflationary, that’s no problem: just increase the monetary base.

Ralph Musgrave –

ISTR Bill’s previously shown that commercial banks don’t really create money – ’tis an illusion, and the money’s really all created by central banks.

Aiden: Not true. There are two basic sorts of money. First, central bank created money, i.e. monetary base or “high powered money”. Second, there is commercial bank created money.

Semantics? You say ‘money’ we say ‘credit?’ Ie commercial banks create credit.

Haven’t read the full paper yet, but this is the core challenge in redesigning the banking system. Everything else is window dressing by comparison.

Pro-cyclical capital strategy should include much tighter regulatory control over the discretion for pro-cyclical bank share buybacks. The record for long term share value is a total disaster.

And I don’t think they should give up on the idea of contingent capital whereby debt is converted to equity pro-cyclically.

Not sure why you characterize this as asset side regulation. There are two components to bank capital requirements. One is risk weighting of assets. The second is the quantity and quality of capital. Both sides of the balance sheet are regulated here – the way in which risk is calculated on the asset side and the way in which that risk is insured on the other side. Also, risk analysis is not limited to the asset side. Capital is also required for market risk and operational risk, whose characteristics permeate the entire balance sheet. (I would guess you may characterize it as asset side regulation as a fit with the MMT policy option of unlimited fed funds.)

And there is quite a contrast implicit here in the importance of excess capital (very high) versus the importance of excess reserves (near zero).

Yeoman’s work, Bill.

As usual.

Hope they’re listening.

My conclusion would be that Basel Accords are variations on the theme that there must be SOMETHING they can do about the pro-cyclicality of our non-permanent, debt-based type of money systems – where money is created and destroyed by making loans, and then another round of the financial instability cycle of Minsky’s hypothesis is again in play.

So, after this, Basel IV?

Gotta agree with Ralph.

Again.

The problem is neither the banking system, nor the financial system, per se.

It is the monetary system.

Thanks, Bill, for letting me say that out loud, your a great bloke yourself.

If money creation – you know the provision within the national economy for adequate circulating medium to provide for the exchange of available goods and services – is restored to our national governments, to whom any true economic democracy would place such an enormous power, then we could tell the BIS they need to get back to studying international balance sheets, with less emphasis on meeting financial stability targets (not defined) through external manipulation of private capital markets.

Basel II and III be damned.

The governments of whom the currency is denominated would now be responsible for financial stability by ensuring the proper level of monetary ‘grease’ to keep supply and demand in motion in their national economies.

This is the opposite of the BIS’ yearning for yet another level of capital-calls aimed at easing the exact pro-cyclicality that comes from what Friedman called “the private creation and destruction of capital” through fractional-reserve banking, using debt-based money.

I still say the monetary policy purposes and mechanisms laid out in the 1939 Program for Monetary Reform were all that were needed for ending the financial instability cycle known as booms and busts.

I often wonder what Minsky would have done with his life under such a system of relative financial stability.

Available here.

http://www.economicstability.org/history/a-program-for-monetary-reform-the-1939-document

Thanks.

Adjusting capital requirements over the business cycle is a decent first step, and a far better approach to macro stabilization than adjusting short-term interest rates.

JKH . . . regarding contingent capital . . . converting debt to equity sounds good. But a number of papers I’ve read on contingent capital have been suggesting instead contracts to provide capital as a payoff essentially to options that go “in the money” when the bank needs more capital or similar sort of trigger (like a mkt event). I find those approaches lacking because it is at precisely the moment that all those contracts go in the money that the ability to make good on them would be in question (i.e., the ability to get st financing to settle such contracts in the midst of a crisis). That wouldn’t be a problem with basic convertible debt as you suggest, though.

Scott,

I haven’t spent much time looking at contingent capital, but I like the basic concept as a complement to an improved regulatory resolution authority.

The problems I’m aware of around the contingent capital concept (forced debt conversion version) are two-fold, roughly:

a) Complications around specifying the trigger event, and associated potential for market gaming

b) Challenges in selling it as a security

I have to think that with a sufficiently high yield there would be a market for it. No doubt it would be a very high cost of capital – closer to pure equity than debt cost.

What about SIV’s? Are they attempts to avoid capital requirements?

I still think one of the best regulators is higher interest rates.

Bill, Scott, JKH,

If we want to disaggregate private sector “savings” monetary flow to emphasise the effects described by Minsky –

In the basic formula:

(S – I) = (G – T) + (X – M)

shouldn’t S be split into

private sector savings equal sum of saving in the form of government money/bonds and the reduction of stock of private loans?

with some (minor) additional assumptions not shown here leads us to

S = dM/dt + dBL/dt -dLh/dt

where

stock of money deposits is M

bonds held by households BL

loans Lh

This would capture the impact on changes of the stock of credit money on the aggregate demand

basically dLh/dt is the measure of leveraging or deleveraging of the private sector

(I took the idea and symbols from page 382 of “Monetary Economics” by Godley and Lavoie – I believe it is guaranteed their balance sheet is correct)

If we look now at the real numbers the gyrations in dLh/dt over time can be quite substantial and it may be a few % of GDP

from RBA’s d02hist.xls

the stock of owner-occupied housing credit:

Dec 2008 $688.2bln Dec 2009 $755.5bln

what generated an additional flow of $67.3bln over 12 months while GDP is estimated to be $1.116 trillion what gives us 6% of GDP

and this was only for home owners – I haven’t mentioned investment housing which probably should be captured in “I”

not all of the money created by the banking system in the form of credit may have been used to purchase final products (new homes)

Please let me know whether I am wrong here as this is how I understand the dynamic process driving bubbles and debt deflation.

I still have to read a lot and I haven’t managed to properly digest the models provided by Godley and Lavoie. Unfortunately it all takes a lot of time…

Thanks,

Adam

Adam (ak),

I’m not in a position to piece together all your data sources, but in reverse order:

Regarding A. housing credit change of $ 67 billion, this type of number is only a partial function of GDP, since much housing credit finances purchases of existing houses. Purchase of existing houses is an asset swap at the macro level with net saving of zero, as opposed to actual saving deployed in new housing as a component of GDP.

Regarding sector financial balances, the government, private sector, foreign sector model is quite macro. Only the government/non-government level is more macro. Each tripartite sector has two bilateral balances with the other two sectors. The private sector has bilateral balances with government and foreign sectors. The balance with the government sector consists of holdings of reserves, currency, and bonds. The balance with foreigners consists of a complex of asset liability positions in numerous categories – e.g. foreign equities held by the private sector; bonds issued by the private sector and held by the foreign sector. Bank deposits are part of it going in both directions.

Decomposing the private sector into the household sub-sector and the business sub-sector is more illuminating, but more complicated. One must “drill down” one more level from the tripartite split into the quadrilateral split. E.g. deployment of saving splits into new household real assets (residential real estate and durables) and the change in household net financial assets. The change in household NFA incorporates among other things the incremental embedded stock market value of the change in retained earnings (saving) of business – tricky stuff in terms of market valuation versus book value saving.

“Deleveraging” is something that is context dependent. It’s about reducing debt in some sense, or reducing the relationship of debt to net worth in some sense, but one must be precise about use in context.

JKH,

Thank you for the response.

I am obviously trying to recalibrate and reconcile with the reality the well-known “Minsky dynamic model”. I believe that the right topology of the flows and stocks comes from Godley and Lavoie rather than the ad-hoc Circuitist micro model and that swings in aggregate demand caused by the speculative activity on the housing market are much smaller than shown by the model.

I think that the effect of the asset swap related to buying existing houses financed by new loans will be an increase in BL and M (bonds and deposits) held by the private sector so they will be absorbed and no net contribution to S will occur.

A has a house B wants to buy

B takes a loan for X dollars (Lh increases by X)

B pays X dollars to A (obviously some money leaks to Real Estate agents, State Government etc)

A deposits X dollars in the bank (M increases by X)

But for a new house X dollars will contribute to aggregate demand flowing through the economy.

Is this correct?

For the mentioned period about 1/6 .. 1/5 of the houses financed were new. This may correspond (yes I know this may not be true) to the amount of credit money injected to the economy which would be then about 1% of GDP

source:

REMOVE_THIS_http://www8.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/allprimarymainfeatures/75E4234DA3B28E16CA2576E100133B66?opendocument

So we don’t have 6% contribution to GDP but still something which may have a significant impact on the economy.

However compensating for 1% loss of GDP if there is a housing slump is not such a big deal provided that extreme neoliberals who want budget surpluses ASAP are not in power.

Bill,

Basel III proposes both capital and *liquidity* standards as you indicated in your message. While you covered the capital provisions a bit, you did not say much about liquidity. I think that ignoring the liquidity part is a mistake. Here’s why:

It is well known and documented, by now, that the 2007-2008 financial crisis started with liquidity problems that developed into full-blown liquidity crisis that led, for some financial institutions, to solvency break-downs.

Let’s imagine imagine bank A granting a loan that results in a deposit in bank B. Obviously, the bank A reserve account has to be funded to make the settlement possible. In the pure and frictionless MMT world, the settlement is not a problem: bank A grants the loan first and looks for funds afterwards, possibly on the interbank market at a small cost of the interbank rate.

In the real and messy world, prudent commercial banks know quite well how dangerous it might be to rely on the interbank market uncollateralized borrowing and they carefully plan, or at least do their best to plan, using rather sophisticated software capable of predicting cash in/outflows in order to fund *future* draw-downs through their retail depository network first and the wholesale market second, in this order, or through selling their liquidity buffer securities or just using buffer cash. In no bank I am familiar with, either in Canada or the United States, is funding predictable loan related or line of credit draw-downs done as an afterthought, through the interbank market. Granted, there were/are commercial banks such as Continental Illinois who relied on fed funds or Northern Rock who funded its activity through brokered deposits and neglected the importance of the traditional core deposits — their fate is well known.

The real or perceived counterparty risk in the interbank market on both sides of the pond led to an IM freeze and to the situation when banks prefer to hoard cash in order to be able to settle their positions.

Basel III is well aware of liqudity risks and the importance of proper liquidity management. That’s why the Basel liquidity proposal, in particular, calls for a 30-day liquidity buffer in order to cover projected net cash outflows after which the bank will either manage to provide required funding or it will be properly ‘resolved’/shutdown.

The MMT proponents do themselves a disservice by painting a simplistic unrealistic and therefore dangerous picture of how interbank settlement occurs (or should occur) in the real world. While the loan-> deposit causality holds in most cases, the mantra “loans make deposits” led some MMT neophytes to state, rather bizarrely, that core deposits do not play much of a role in the modern banking. In this thread, JKH stated that “the importance of excess reserves [is] (near zero).” Fortunately, the Basel folks think differently wrt ‘reserves’ aka “liquidity buffers”.

Thanks.

Adam (ak)

Looks OK to me, but again I’m not familiar with Australian data classifications.

VJK,

You’re right. Liquidity management is very important, and I was wrong to reference it in such a slipshod fashion. For an individual bank, it’s about ensuring operationally smooth access to reserves – not to be relying on last resort type funding. That sort of access to reserves is generally managed by sensible liquid asset policies, and the development of retail and wholesale funding networks.

The MMT point is that central banks generally provide the reserves that the system requires in total; it’s then up to the individual players to compete effectively at all times for their required share of system reserves.

In normal environments, the macro provision of excess reserves by the central bank is for purposes of interest rate control over the policy rate. At the margin of reserve management, whether an individual bank has a treasury bill to sell in exchange for reserves or the reserves themselves is not that important, and it may have been in that sense I was making the reference. There’s no corresponding systemic mechanism regarding a macro provision of the capital that the banking system requires, at least not in normal operating circumstances. So it is in that sense that a marginal excess capital position is more significant than a marginal excess reserve position. But you’re right to point out the critical importance of ongoing liquidity management in general.

VJK,

Good points about banks’ worries. In fact it was precisely the reason Bank of Japan did the Quantitative Easing operations and the ECB started the LTROs in large scale in 2009.

VJK, you are correct but your example tells how misplaced current regulation is.

As long as bank has sufficient capital vis-a-vis its assets and cash flows that they can generate, it is quite clear that this bank is a viable business. Liquidity considerations actually become external and in a proper design should be automatically addressed by the central bank. This is exactly, as Ramanan said, what happened during this crisis. So in terms of regulations it might make sense to provide unlimited liquidity to commercial banks on ongoing basis and devote much more time and attention to real risks of banks which is credit risk. This concerns not only central bank efforts but also significant efforts undertaken by each and every bank in this world.

Sergei,

Uncollateralized money markets are based on trust. For example, when interbank market participants suddenly realize, correctly or incorrectly, that the counterparty credit risk cannot be judged with a sufficient degree of confidence (asymmetric information), the market breaks down very quickly as no one can trust anybody any more. Thus, counterparty risk feeds liquidity risk and vice versa in a sort of self-reinforcing positive feedback loop. As I said earlier, the counterparty real or perceived risk leading to liquidity break-down leading to insolvency collapse is recent, well-known to anyone who bothered to look at the events, documented and even researched in numerous academic and non-academic publications.

So, your suggestion to concentrate mainly on credit risks won’t work in the real world due to the bank-participants opaqueness, as was discovered during the GFC, which makes counterparty risk estimation close to impossible, at least for now. In the light of the latest Goldman Saks pronouncements to the effect that the dog-eat-dog modern financial menagerie ‘culture’ is normal (see the Abacus debacle), it would be naive to rely on the old-world dying culture of trust (Canada may be somewhat of an exception, but for how long ?). That leaves us with a voluntary or regulation imposed mandatory liquidity cushion option, *or* with a fully accomodating central bank. The latter represents an obvious moral hazard, ‘Bernanke’s put’, and besides the f.a. CB is not what we have in our current reality unless you count the aforementioned ‘put’.

VJK, you misread my comment. The argument was exactly for unlimited liquidity provided by the Central Bank which, by the way, should have the best information about capital position of commercial banks. Any liquidity regulation tries to obscure the real problem behind bank runs which, as you said, is trust. In banking trust equals capital. So unlimited liquidity provision is no moral hazard since it relies fully on proper capital position of the bank. Banking business is by definition a long-term business. Any bank with cash generating capacity of its assets being justified by its capital position is a viable banking concern. Liquidity risk is then one of those short-term destructive forces which can not add any value but only destroys it. It is a cost of business which is not required by nature but is rather imposed by misplaced regulation. And government is there not just to regulate for the sake of bureaucracy but to minimize and cure market deviations from socially efficient outcomes.

Bill-

Is it possible for you to comment on the paper by Kalecki regarding a capital tax as a counter-cyclical buffer?

http://gesd.free.fr/kalecki43.pdf

I would be very interested in your opinion.

VJK,

You make some excellent points, including a couple that I have attempted to make here previously, although probably with less clarity.

In a banking crisis or time of stress, the imagined distiction between a “liquidity problem” and a “solvency problem” breaks down. Banks rarely suffer from liquidity problems without some underlying uncertainty over their long-term solvency. Solvency concerns feed liquidity concerns and vice versa.

Also, I agree with your observation that within the MMT community (and other “alternative” economic communities) there are some big misconceptions about the way the banking system actually works. Much is made of the fact that the “money multiplier” model of banking is incorrect, but in the excitement of this discovery, some have latched onto an equally incorrect and crude caricature, this notion that “loans create deposits”, and that the central bank will supply all required funds and that banks do not worry about sourcing deposits or funding.

In reality the causality is not that clear and simple. The demand and supply of loans and deposits will effect one another, and it is not possible to say “deposits cause loans” (as the money multiplier model does) or “loans cause deposits”.

And banks most certainly have to source deposits. No bank in Australia funds their loan book in the overnight funds market, nor could they.

Sometimes it is necessary to talk simplistically (that is, ignoring qualifications and detail) to get your point across. One expects full articulation and data in professional publications, but blogs posts and comments are another matter. There is always a level of detail is just too complicated for people not familiar with the subject (most blog readers) to grasp. I think that Bill hits a pretty happy medium. Often, the comments elaborate the finer points. Often, I have to read through some of this several times, and even then I don’t get all. But over time it dawns, when the points are repeated from different angles.

For example, the complications of “loans create deposits” have been explained previously in posts as well as in extensive comments, e.g., by JKH and some others who are knowledgeable about banking operations. But when addressing someone that says “deposits create loans” or “banks lend on reserves,” then a simple counter like “loans create deposits, and reserves follow” is in order. Usually, the people making such claims don’t have a clue about banking operations anyway, and trying to explain the details to them would be useless. I’ve tried, even though my knowledge is very limited; they can’t even get that much. Moreover, in a blog that aims to be accessible, it would not a appropriate for the level of the readership.

If this rule were followed, neoliberals would never be able to say anything because anyone who is not an accomplished econometrician could not understand what is being said. Same with every field of any complexity. Complex issues get boiled down and in the course of it, a lot gets lost that people familiar with the field know is somewhat misleading.

For this reason, elaboration in the comments is a great service. I admit that sometime some of this goes beyond me at the moment, but over time I start to catch the drift. So thanks for the detailed explanation. I know enough now to follow this discussion, although when I started out it would have been beyond me.

This is the political problem, and it is why technocrats want politically independent control as much as possible. That has advantages and disadvantages politically. Democracy is sacrificed to efficiency and the presumption is made that the technocrats in charge have it right. That’s a problem.

I think that Sergei basically has it right here. The financial sector is fundamentally broken, when the players no longer trust each other. At one time deals were done on a handshake, with the knowledge that anyone who went back on it would automatically be blackballed. Trying to add regulation doesn’t work in the end. The incentives have to be changed, accountability strengthened, and sunshine introduced.

I am almost with Bill in calling for a switch to public banking across the board. But over time, that will become corrupt, too. No system is perfect, because human beings are not perfect. So, “the price of freedom is eternal vigilance.”

Gamma, loans create deposits and it is an accounting fact. However as Tom says format of blogs requires some corners to be cut and certain concepts to be simplified. But this does not mean that these concepts are wrong. Yes, you are right that banking is more complex than “loans create deposits”. But does it really add extra value to the message of a blog? One should not expect every aspect to be covered in a blog post which is just a couple of pages long. However if you want to add complexity feel free to do it. There are no dogmas on this blog and discussion is always open.

Regarding your concerns. In real life in banking asset generation and liability generation functions in operational sense are pretty much independent businesses. Reason? Because there are too complex on their own to mix them together. However the typical business cycle dictates the following logic: 1) assets are planned 2) funding needs and structure are determined 3) both points are executed. Critical point is that they are executed upon independently. But by looking closer you can still see that assets (loans) generate deposits (funding needs) and this is a conceptual point.

I’m with Sergei and Tom here. Further, I don’t see that the issues brought up by VJK and Gamma are correct interpretations of MMT. When I’ve challenged VJK on it, he found one quote from one person (Winterspeak) on one blog from 1.5 years ago. And when did any of us say that banks don’t have to concern themselves with the their liability side? Only if one twists our words to mean something we didn’t actually intend can that be true.

On a lighter, but related note, as Sergei suggests, if VJK or Gamma put together what either of them considered to be a very careful description of bank operations, from their comments I’ve seen in the past I doubt MMT’ers would have much to disagree with.

A big bank can have $ 50 billion in liquid assets, broad sources of liability funding, and do meticulous liquidity and cash management planning in order to match assets and liabilities in a reasonably deliberate fashion on a daily basis (and they do). In a “normal” banking system environment, involving no quantitative or qualitative easing, the central bank will provide the reserves that the system demands in order to equilibrate the short term policy interest rate, and no more reserves than that. In such a normal environment, banks will seek to manage their excess reserve positions to a very fine margin, on a daily basis.

There is nothing in that set of facts that invalidates the MMT idea that loans create deposits, or that the banking system doesn’t need excess reserves in order to lend, or that individual banks don’t need reserves before the fact in order to lend. Yet that scenario involves very prudent cash and liquidity management on the part of the banks. And there is certainly nothing implicit in the MMT approach to this subject that suggests banks routinely rely on overnight funding. Banks attract all manner of maturities of retail and wholesale funding on a daily basis and do it for a reason and price for it. One of the MMT points is simply that the central bank is there as a last resort source of reserves if needed by individual banks. That point has never suggested that banks routinely manage their liquidity affairs in such a reckless fashion as to routinely take advantage of such a last resort facility. (One interesting example of this is that even in the depths of the financial crisis, Goldman Sachs, having turned itself into a bank with normal Fed access, only once tested the primary credit line it had received from the Fed in doing so – and only for $ 10 million.)

Gamma:

Re. “In reality the causality is not that clear and simple.”

Recent empirical research (http://epublications.bond.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1058&context=theses) confirms earlier Howells and Hussein findings wrt. loans-deposits Granger causality for G-7 banking systems. Mostly, the causality is bidirectional (not surprisingly) although money supply is predominantly endogenous except UK and US until the monetary regime change in 90’s when money supply had apparently been, according to the research, exogenous.

Sergei:

“In real life in banking asset generation and liability generation functions in operational sense are pretty much independent businesses.”

Not in Canada where there is a close cooperation between loan officers and liquidity managers. How else can a liquidity manager anticipate and cover cash outflows without any information about loan and line of credit related draw-downs ? How can loans/LoC even be properly priced without employing something like FTP (fund transfer pricing) ? Now, perhaps there are more commercial banks like Northern Rock that may have built a Chinese wall between those responsible for granting loans and the liquidity[risk] managers, I don’t know.

Scott:

The gentleman in question has recently re-iterated his 1.5 year old conviction that core deposits are not needed in the same thread. The statement is quite funny to any bank practitioner who knows that, statistically, demand deposit cash inflows move in the direction opposite to line of credit down-draws. That practical observation has been reflected, for example in this research paper: http://fic.wharton.upenn.edu/fic/papers/06/0609.pdf.

Thanks.

I should add to my 8:33 that the whole purpose of bank reserve management is to match assets with the sum of liabilities and equity in notional terms. In that sense, the reserve account at any point in time is a mirror image of the notional match or mismatch on the rest of the balance sheet (including any statutory requirement for some minimum reserve level). And it is the incremental activity across the rest of the balance sheet that drives sources and uses of reserve funds. Those that understand MMT would never say that banks don’t need deposits any more than they would say banks don’t need loans. That’s the broad function of banking, and the main substance of notionally matched assets with liabilities and equity. And they would never say that banks don’t use reserves when they settle the transfer of funds to other banks, or that banks don’t source reserves when they settle the transfer of funds from other banks. What MMT does say is that there is no requirement for new system reserves at the precise point where the banking system creates new loans. Similarly, there is no need for an individual bank to expect a system injection of new reserves when it makes a new loan. And similarly, given the reasonable sophistication of normal bank liquidity management practices (e.g. typically large stockpiles of non-reserve liquid assets, and various sources of new funding liabilities), there is no need for either the system as a whole or individual banks to stockpile reserves per se prior to making new loans. This latter point, when combined with the fact that central banks normally set and provide any required increase in any statutorily required minimum reserve level following the new deposit activity that generated the requirement, is in essence the refutation of the bogus textbook multiplier theory.

JKH,

Very well said, if that’s the ‘official’ position of MMT high powers, cool. Much better that the statements below:

Mosler:

Loans create deposits. Most people believe you need funds, deposits, or savings to lend. Absolutely not true.

Bank capital NOT a constraint on lending

http://moslereconomics.com/2007/12/05/bank-capital-not-a-constraint-on-lending/

“Not in Canada where there is a close cooperation between loan officers and liquidity managers. How else can a liquidity manager anticipate and cover cash outflows without any information about loan and line of credit related draw-downs ? How can loans/LoC even be properly priced without employing something like FTP (fund transfer pricing) ?”

The reporting of current loan activity to the liquidity manager is a function of requirements based on relevant notional limits. The vast bulk of dollar volume of clearings is not reported in this way.

The Royal Bank branch manager in Eyebrow, Saskatchewan does not notify the Bay Street reserve manager that he is making a $ 100,000 loan to his top customer, despite the fact that he’d probably feel good in doing so. On the other hand, infrequent and particularly large items may be reported for heads up purposes.

Bank transfer pricing systems are mostly about macro interest rate risk management and benchmark pricing for both loans and deposits. They have virtually nothing to do with daily reserve management, which is the relevant MMT operational focus.

VJK,

That’s my reading of what MMT says, or should say, based on what I think I understand about MMT.

I’ll hear about it if MMT disagrees with it or qualifies it.

Yikes. Don’t get me started on capital.

Hadn’t even seen that Mosler piece; thanks.

That’s not the way I’d present it, and haven’t in the past. Although I understand that view.

Use of the word “constraint” is a very delicate exercise; it can be quite context dependent, where the context and its boundaries need to be defined quite clearly.

I think I’ll pass on a response for the moment. But I would approach the general idea of a capital constraint somewhat differently.

FYI, big reserve player:

http://townofeyebrow.com/

VJK . . . as I told you previously, Mosler’s point (if you read it) is clearly referring to a bank’s sustainable growth rate. If they achieve a particular return, capital is replenished to enable them to grow assets at that rate. You’ve conveniently left out repeatedly another sentence in that same link where he says “And banks currently do have a lot of ‘room’ for lending with current capital levels,” perhaps because it doesn’t fit your repeated attempts to portray MMT a particular way. Having talked to Mosler for years about these issues, I highly doubt JKH and him disagree in any significant way, but I could always be wrong I suppose.

Scott,

I think that’s right. I agree that capital is mostly endogenous to the general banking system flow of funds, that banks normally generate the capital they require internally, and that if required there is a price at which new capital can be sourced through equity raises that are essentially endogenous deposit conversions. I’d refine it somewhat to include reference to what is typically a sophisticated framework for making micro decisions on alternative allocations for capital within a given banking organization, given a finite level of capital at any point. And at the macro level, I’d refine it by observing that in the normal course there is no system provider of sufficient capital funds the way there is for reserves. Those sorts of refinements go to the point of defining exactly what one means by the word “constraint”, in context.

JKH . . . I agree completely. Thanks.

Scott:

I am disappointed about that: “perhaps because it doesn’t fit your repeated attempts to portray MMT a particular way.” Is it a thinly veiled attempt at an ad hominen, at least in tone ? Is ad hominem a generally accepted argument pattern amongst economics professionals ?

There is no need to ascribe any sinister motives to my comments and assume a defensive position — they are what they are: attempts to clarify MMT’ers position on certain issues and dispel misconceptions, whenever I see those misconceptions, about those issues. JKH comments were quite useful, by the way, and I want to thank him.

One can certainly tap dance around Mosler’s “no capital”, no funds” comments, but they speak for themselves as it were.

I’m sorry, VJK, but you’ve repeatedly misrepresented the views of MMT’ers even when the actual meaning already has been explained to you. It has given the appearance, valid or not, that you have a chip on your shoulder against MMT. Such comments, particularly where repeated as you have done, are the actual ad hominen at play here. If you are truly just trying to clarify MMT’ers positions, then simply say so. Instead, you say ‘the typical MMT view is X and here are the reasons X is wrong.’ That is quite different from simply seeking a clarification or attempting to dispel a misconception, particularly where your description of MMT’s understanding of X is usually wrong, and where it has been previously explained to you that your description of MMT’s understanding of X is wrong.

To extend the Mosler case, he was responding to Jan Hatzius’ arguments in late 2007-early 2008 that bank capital would fall by X amount, and this would, result in 10x (or something like that) reduction in total bank lending capacity. His point was to explain the endogeneity of bank capital basically as JKH was putting it for the system as a whole and I was explaining for an individual bank. This isn’t tapdancing–context matters–and it wasn’t the first time you had seen these explanations in response to this exact misrepresentation.

Having read through the comments here I’m still no clearer as to what *are* the restrictions on bank lending and what is the direction of causality. Nor am I clear as to what evidence there is to show that is the case.

Are the restrictions and causality somehow different at macro level than they are at the micro level of an individual bank?

Neil, there is no formal direction of causality in the current system where banks have to take care of their liquidity position because regulation requires. Assume there is no liquidity regulation and CB always stands ready to provide unlimited liquidity to any bank with sound capital position then the causality will become explicit. So with existing regulations bank do have to take care of liability side.

However asset and liability businesses are absolutely independent in operational sense. The FTP system that VJK is referring to is not a “talking” mechanism between assets and liabilities. It is a matching mechanism which relies much more on business strategy than current market conditions or bank position in terms of its liquidity.

“Having read through the comments here I’m still no clearer as to what *are* the restrictions on bank lending and what is the direction of causality. Nor am I clear as to what evidence there is to show that is the case.”

I’ll give this another shot, since I seem to be in the mood.

The “restrictions” on bank lending as it pertains to this discussion are that banks at both the macro and micro level must be adequately capitalized to support lending and other forms of risk taking. My personal interpretation has been that this is a form of constraint, where “constraint” is defined in that context. If a bank is not adequately capitalized, it must raise capital or incur the wrath of the regulator, at least. This was the purpose of the “stress tests” for the banks in both the US and Europe. Some banks were/will be forced to raise capital as a result of those tests.

The Mosler view as described in the link noted above is that bank capitalization is an endogenous phenomenon and is not a constraint. This is because banks typically generate adequate capital internally and if required can raise capital externally by pricing the transaction so as to attract the required market appetite for new bank equity. At the right price, enough people will trade deposits for new bank shares. I don’t have a problem with that interpretation, using “constraint” in that context. That use is not in conflict with certain banks failing their stress tests and having to raise capital, because indeed they did raise capital successfully (so far, in the US).

In the case of reserves, the central bank provides adequate reserves to the banking system in total in order to ensure the regular operation of the system at targeted policy interest rates and meet any additional balance sheet requirements of the central bank (e.g. quantitative easing). In particularly stressed environments, individual banks may have difficulty meeting their own reserve requirements without accessing central bank credit. This can be due to systemic market turbulence and/or specific bank funding problems. The latter can be associated with market fears of capital adequacy, which has a knock on effect for day to day liquidity operations.

The general MMT view is that banks are not reserved constrained in lending because of the central bank’s pivotal role in providing adequate system reserves and because of commercial bank access to last resort central bank credit. That does not mean that individual banks cannot face difficulty in funding through regular channels in certain unusual circumstances as noted above. If particular banks face severe funding pressures at a chronic level, it’s likely that will be associated with market perception of their capital position as well, and it’s quite possible that their lending operations will be affected at least temporarily in that dually stressed liquidity/capital situation. But that is not the normal banking situation at all, and it’s usually capital related as well.

Quite apart from this fine tuning of the meaning, the main purpose of noting that “banks are not reserve constrained” is to dismiss the incorrect textbook explanation of the multiplier, which insists that banks lend AS A FUNCTION OF some pre-supplied/sourced stock of excess reserves at both the individual and systemic levels. That textbook causality is absolutely incorrect. Banks lend as a function of credit worthy demand, provided they are adequately capitalized to support the risk assessment attached to any new lending and assuming they practice normal and prudent liquidity management to ensure ready access to their required share of existing system reserves when they need them for settlement of new transactions.

P.S.

The final paragraph of 21:07 above explains why the current $ 1 trillion in excess reserves at the Fed has nothing to do with bank lending motivation. Banks lend according to risk assessment and capital allocation. The $ 1 trillion excess is simply another form of liquidity for banks, ensuring access to settlement balances in much the same way as treasury bill or other liquid asset holdings. There is widespread misinterpretation of this system excess reserve position, across in the blogosphere and by economists at large, MMT / Post Keynesians excepted.

VJK,

“Loans create deposits. Most people believe you need funds, deposits, or savings to lend. Absolutely not true.”

I could not see this quote you attibuted to W. Mosler in the link: http://moslereconomics.com/2007/12/05/bank-capital-not-a-constraint-on-lending/

Did I miss it, or was it somewhere else? It looks like a clanger to me, but it is out of context of course.

JKH:

“Bank capital grows endogenously- it’s not a constraint on lending apart perhaps from the very near term.”

At the risk of raising Scott’s suspicions about my dark designs wrt.MMT even further, I’d like to kick this dead horse {Mosler’s capital comment) one last time:

1. The remark about bank raising capital endogenously is, well, pretty trivial as credit creation on *all* credit markets, be it bond markets, stock market or any arbitrary IOU market is as endogenous as credit money creation at a bank. What deep insight am I missing ?

2. Trying to raise capital in December 2007 for any bank at any market, endogenously or otherwise, would be a pretty tough affair, no (bailout measures immediately spring to one’s mind) ?

In my humble opinion, upon re-reading, the bank capital comment quality is not terribly high and the heading is truly misleading even when taken in the context unless of course I am missing something.

JKH:

The current $ 1 trillion in excess reserves is mostly if not solely the result of trust loss in the interbank market. The banks willingly hoard the extra cash just to be able to settle their reserve accounts without reliance on the broken network of trust.

I am wondering whether any data is available as to excess reserve distribution among major US banks (I doubt).

I agree with everyone here that in the narrow sense banks are not materially constrained by their reserve balances at the the central banks (ie for Australian banks these are called exchange settlement balances). We don’t even have minimum reserve requirement here in Australia.

However a couple of observations:

1) Some people incorrectly extend this idea to the belief that banks are not constrained by deposits, and that banks do not need to source deposits or debt funding. This is wrong. You can think of it in the sense of liability management, or the more traditional notion that banks borrow money from the public (depositors or bond holders) to lend, but either way it is the same – banks must source deposits/funds. I’m not saying this is the “official” MMT position, but it is an occassional misunderstanding amongst people on this site and others.

2) Banks are not directly constrained by reserves (exchange settlement balances) but this does not mean that reserves are irrelevant. Banks are constrained by the amount of capital they have in relation to their risk-weighted assets. Reserves are a form of asset which are allocated zero risk weighting in the capital adequacy ratios (as opposed to mortgages which have a higher risk weighting). The large amount of reserves in the US banking system may not be having an effect on bank lending at the present moment, but there may come a time when they do.

3) In Australia, government and semi-government debt plays an essential role in the cash and money markets. These debt instruments can be considered a kind of quasi-money as banks hold them in their liquidity portfolios as an immediate source of funds in leau of exchange settlement deposits. There are 2 reasons banks hold securities rather than ES balances – (1) ES balances receive 25bps less than the cash rate and (2) the semi-government securities trade at a small yield premium for the risk on the semi-sovereign issuers. This quasi-money is far more important than the cash balances, but receives very little attention in posts and comments.

4) Why is this whole thing about reserves such a big deal anyway? Seems very much like an academic argument, in all senses.

Thanks all

“The general MMT view is that banks are not reserved constrained in lending because of the central bank’s pivotal role in providing adequate system reserves and because of commercial bank access to last resort central bank credit”

The central bank doesn’t provide them for free though AIUI. There has to be collateral and they pay an interest rate. I understood that the collateral is usually a government bond.

So I don’t see how that gets us anywhere. The bank has to have a store of government bonds to get central bank funding.

Memo to self: Tattoo on wrist:

JKH:

VJK, it seems to me there were two issues at the beginning of the crisis, liquidity and solvency. After the failure of Lehman and general knowledge that a lot of institutions were in trouble, the interbank market froze and the Fed had to step in as LLR. That was proper and correct. Then, what “should” have happened under the law and regs didn’t happen. Instead of putting the insolvent institutions into resolution, the government in its infinite wisdom decided to put into effect a plan that is still unfolding to conceal their situation and let them recapitalize by giving them favorable conditions to do so. The banks subsequently showed their gratitude by stiffing the people that saved them.

Much of the extra 1T in reservers is the result of QE which has more to do with influencing long term rates, which the Fed did by buying MBS dreck to get it off the big banks books. So it was part of the rescue plan, not a direct provision of liquidity.

At least from my perspective.

Gamma:

I am glad I am not alone in my puzzlement regarding your point (1) .

Thanks.

VJK,

“What deep insight am I missing?”