Today, we solve the 'Case of the Missing Report'. Recall from - The Case of…

Zimbabwe for hyperventilators 101

Zimbabwe is the new Weimar Republic. Not! Zimbabwe is the front-line evidence that shows that government deficits will generate hyper-inflation. Not! Zimbabwe is the demonstration of the folly of a fiat monetary system. Not! Zimbabwe is an African country with a dysfunctional government. Yes!

First we should make sure what we are talking about. The right think that when the workers get a pay rise it is inflation. It is not. The left think that when the corporate sector increase the price of a good or service it is inflation. It is not. It is also not inflation when the exchange rate falls pushing the price of imports up a step. It is also not inflation when the government increases a particular tax (say the GST) by x per cent to some new level.

So while a price rise is an essential pre-condition – a necessary condition – for what we call inflation it is not a sufficient condition. That is, the observation of a price rise will be required to define an episode as being inflationary (at some point) but observing a price rise alone will not be sufficient to categorise the phenomena that you are observing as being an inflationary episode.

Inflation is the continous rise in the price level. That is, the price level has to be rising each period that you observe it. So if the price level or a wage level rises by 10 per cent every month, then you have an inflationary episode. In this case, the inflation rate would be considered stable – a constant rise per period. If the price level was rising by 10 per cent in month one, then 11 per cent in month two, then 12 per cent in month three and so on, then you have accelerating inflation. Alternatively, if the price level was rising by 10 per cent in month one, 9 per cent in month two etc then you have falling or decelerating inflation.

If the price level starts to continuously fall then we call that a deflationary episode.

Hyper-inflation is just inflation big-time!

So a price rise can become inflation but is not necessarily inflation. Many commentators and economists get this basic understanding wrong – often and continually.

Second, it also follows that cyclical adjustments in price levels by firms from what they are currently offering at depressed levels of activity to what the price levels that are defined at their normal operating capacity levels are also not sensible to consider as inflation. When the economy is in poor shape, firms cut prices in an attempt to increase capacity utilisation by temporarily suppressing their profit margins and hence maintain market share. As demand conditions become more favourable the firms start increasing the prices they offer until they get back to those levels that offer them the desired rate of return at normal capacity utilisation. Have you tried hiring hotel accommodation recently in the tourist areas? Big discounts are on offer but they will disappear once the economy improves. It is not helpful to call that inflation.

Responsible fiscal practice

Now at the risk of repeating myself a million times, this is the macroeconomic sequence that defines responsible fiscal policy practice. This is basic macroeconomics and the debt-deficit-hyperinflation hyperventilating neo-liberal terrorists seem unable to grasp it:

1. The sovereign government, which is not revenue-constrained because it issues the currency, has a responsibility for seeing that the workforce is fully employed.

2. Full employment means less than 2 per cent unemployment, zero underemployment and zero hidden unemployment.

3. The sovereign government can purchase any real good or service that is available for sale in the market at any time. It never has to finance this spending unlike a household which uses the currency issued by the sovereign government. The household always has to finance its spending (as do state and local governments in a federal system).

4. The non-government sector typically decides (in aggregate) to save a propoportion of the income that is flowing to it. This desire to save motivates spending decisions which result in the flow of spending being less than the income produced. If nothing else happened then firms would reduce output and income would fall (as would employment) and households would find they were unable to achieve their desired saving ratio.

5. The government sector must in this situation fill the spending gap left by the non-government sector’s decision to withdraw some spending (in relation to its income). If the government does increase its net contribution to spending (that is, run a budget deficit) up to the point that total spending now equals total income then firms will realise their planned output sales and retain current employment levels.

6. The government sector’s net position (spending minus revenue) is the mirror image of the non-government’s net position. So a government surplus is equal $-for-$, cent-for-cent to a non-government deficit and vice versa. So if the non-government sector is in surplus (a net saving position) then income adjustments will render the government sector in deficit whether it plans to be in that state or not. If income is falling in fhe face of rising saving behaviour of the non-government sector and that spending gap is not filled by government net spending then the budget deficit will rise (as income adjustments cause tax revenue to fall and welfare payments to rise). You end up with a deficit but the economy is at a much less satisfactory position than would have been the case if the government had have “financed” the non-government saving desire in the first place and kept employment levels high.

So a responsible government will attempt to maintain spending levels sufficient to fill any saving. You will note I have discussed this in broad aggregates (government – non-government) rather than taking the so-called leakages and injections approach which decomposes the non-government sector into foreign and domestic and considers tax, saving and import leakages against the government spending, investment and export injections. No particularly interesting things emerge at that level of aggregation which are relevant here. We get all the basic insights by keeping it simple.

Getting causality right

If we think about the Weimar Republic for a moment, the problems for them began long before the hyperinflation, which really went off in 1923. Following World War I the reparations payments required under the Versailles Treaty squeezed the German government so badly that they eventually defaulted. The Treaty was just a bloody-minded pay-back by the victors of the war and brought so much subsequent grief to the World in the 1939-1945 War that you wonder what was going on in their heads.

Anyway, for historians, you will recall that the French and Belgian armies then retaliated after the German default and took over the industrial area of the Ruhr – Germany’s mining and manufacturing heartland. The Germans, in turn, stopped work and production ground to a halt. The Germans kept paying the workers in local currency despite limited production being possible and you can imagine that nominal demand quickly started to rise relative to real output which was grinding to a halt. The crunch came when the export trade stalled and the only way the German Government could keep paying their treaty obligations etc was to keep spending. The inflation followed.

But think carefully about the causality here – it was not a normal situation at all where a sovereign government was trying to finance the saving desire of the non-government sector and keep employment and output levels high.

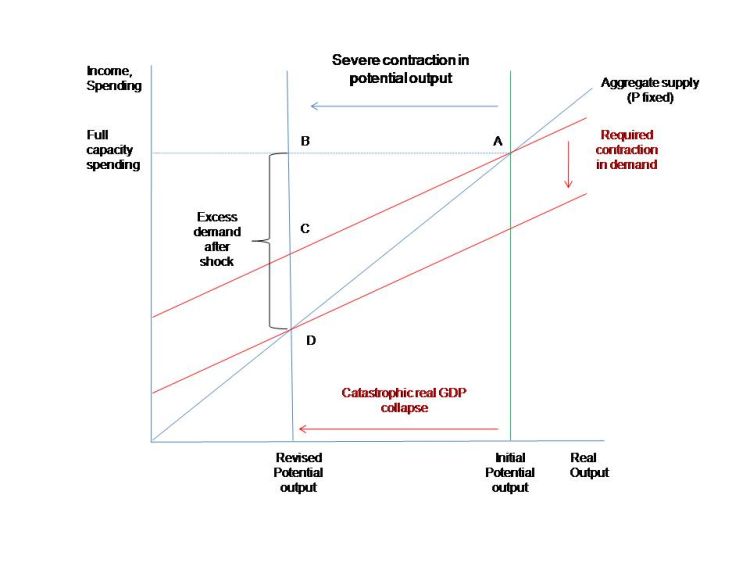

I sketched the following simple diagram to give you an idea of what might go on when a severe supply shock (contraction) occurs. It is not perfect but makes the point (you have to impose your own dynamic motion on the chart). The horizontal axis is real output and full-employment potential output is shown by the vertical green line (inferring no bio-unsustainable production levels!) The vertical axis is spending or demand in real terms. The trick is that the price level is held constant in this diagram. The 45 degree line is the fixed-price aggregate supply curve indicating that firms will supply whatever is demanded at the fixed price up to capacity (Point A). After A, supply capacity would be exhausted and inflation would then enter the picture.

The red line (top) which intersects Point A is the aggregate demand line and shows the current state of spending in the economy at different real income levels. It is upward sloping because consumption rises with national income and it is less than 45 degrees because not all income is consumed (some saving). So it is the sum of all demand components (consumption, investment, net exports and government spending).

If we assume that shangri la prevails then we are initially at Point A. There will be full capacity output, stable prices, some non-government saving and a budget deficit to match.

Now imagine that some dictator comes along and starts taking land off the original farmers (who were productive) and gives it to those who do not understand how to farm or have no real interest in farming, in this primarily agricultural economy. The potential output would steadily contract and I have shown a particular revised potential line (a contraction of the overall capacity of the economy to produce).

If you think about current demand levels in relation to that new dramatically reduced supply potential you quickly see there is a huge excess demand (spending) measured by the gap between Points B and D. But, in fact, as the income levels fall, the economy would actually contract along the top red aggregate demand line (as income falls, so does consumption and saving). At Point C there is still excessive demand (spending) in relation to the new potential capacity.

So demand would have to be reduced downward (red line shifting down) until it intersected the new supply constraint at the 45 degree line at Point D. Point C could theoretically be associated just as much with a budget surplus as a budget deficit – that is, you cannot directly implicate the conduct of fiscal policy with the excess spending automatically or even necessarily.

The upshot is that the price level would be rising in this economy long before it reached Point D from Point A because of the chronic excess spending relative to the dramatically lower capacity.

Zimbabwe …

The hyperventilators out there in debt-deficit hysteria land have been increasing using Zimbabwe as their modern equivalent of the Weimar Republic and as the front-line attack dog in their squawking campaign to get rid of deficits again. The problem is that they clearly have not read much history nor analysed Zimbabwe very well at all.

It is obvious that the nice coloured Zw currency has steadily been debased and replaced by notes with more and more noughts on the end of the 1.

So what went on? The Zimbabwean Government is sovereign in the Zw dollar, although recent decisions to allow US dollars to freely trade within the economy is likely to undermine that sovereignty if tax collections in Zw become difficult to achieve.

In the same way that the Treaty of Versailles was directly responsible for the plight that Germany found itself in during the 1920s, the white racist regime that ruled prior to 1980 and which had broken away from the colonial arrangements with Britain, set up the conditions that are now destroying Zimbabwe. White minority rule in Colonial Africa created such an unfair sharing of land between the whites and blacks that a backlash was always going to occur. The same sort of breakdown will threaten South Africa which is trying to reinvent itself (peacefully) in the post Apartheid era (not very successfully may I add).

Whites who constituted 1 per cent of the population owned 70 per cent or more of the productive land. After the civil war of the 1970s and the recognition of independence in 1980s, Mugabe’s government more or less oversaw relatively improved growth with stable enough inflation outcomes.

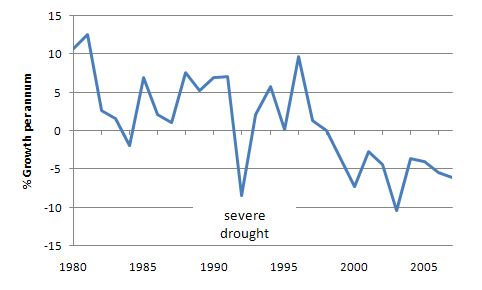

In this World Bank Report 1995 you see the data shows that the economic performance was variable but reasonable. The economy underwent a severe drought in 1992-93 which pushed the inflation rate up but it soon came back to usual levels.

The following graph is of GDP growth since independence in 1980 to 2007 (data from IMF). The performance up until about 2000 provided no sign of the disaster that has followed. GDP growth looked to be like many other nations – variable and usually positive except for the harsh drought in 1992-93.

The problems came after 2000 when Mugabe introduced land reforms to speed up the process of equality. It is a vexed issue really – the reaction to the stark inequality was understandable but not very sensible in terms of maintaining an economy that could continue to grow and produce at reasonably high levels of output and employment.

The revolutionary fighters that gained Zimbabwe’s freedom from the colonial masters were allowed to just take over productive, white-owned commercial farms which had hitherto fed the population and was the largest employer. So the land reforms were in my view not well implemented but correctly motivated.

Like the allies after Versailles, you sometimes do not get what you wish for. The whites in Zimbabwe had always been reluctant to share with the majority blacks and ultimately reaped the nasty harvest they sowed.

From an economic perspective though the farm take over and collapse of food production was catastrophic.

Unemployment rose to 80 per cent or more and many of those employed scratch around for a part-time living.

So the land reforms represented the first big contraction in potential output. A rapid demand contraction was required but impossible to implement politically given that 45 per cent of the food output capacity was destroyed.

The situation then compounded as other other infrastructure was trashed and the constraints flowed through the supply-chain. For example, the National Railways of Zimbabwe (NRZ) has decayed to the point the capacity to transport its mining export output has fallen substantially. In 2007, there was a 57 percent decline in export mineral shipments (see Financial Gazette for various reports etc).

Manufacturing was also roped into the malaise. The Confederation of Zimbabwe Industries (CZI) publishes various statistics which report on manufacturing capacity and performance. Manufacturing output fell by 29 per cent in 2005, 18 per cent in 2006 and 28 per cent in 2007. In 2007, only 18.9 per cent of Zimbabwe’s industrial capacity was being used. This reflected a range of things including raw material shortages. But overall, the manufacturers blamed the central bank for stalling their access to foreign exchange which is needed to buy imported raw materials etc.

The Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe is using foreign reserves to import food. So you see the causality chain – trash your domestic food supply and then have to rely on imported food, which in turn, squeezes importers of raw materials who cannot get access to foreign exchange. So not only has the agricultural capacity been destroyed, what manufacturing capacity the economy had is being barely utilised.

Further, goods and services have also been prevented from flowing in via imports because many importers abandon goods at the border when they are hit by exhorbitant import duties.

Taken together, the collapse of production has seen the unemployment rate rise to 80 per cent or more. The rising unemployment has further choked any household income growth and aggregate demand has fallen even further.

As a consequence, GDP growth has been contracting at around 7 or 8 per cent per year and the economy’s potential capacity level has been falling dramatically as investment dries up.

Further, the response of the government to buy political favours by increasing its net spending without adding to productive capacity was always going to generate inflation and then hyperinflation.

But while the hyperinflation was almost inevitable it provides no intrinsic case against a government that is sovereign in its own currency and who runs permanent deficits to pursue full employment – under the guidelines specified above – responsible fiscal management.

When you so comprehensively mismanage the supply side of your economy as the Zimbabweans did the only way to avoid inflation is to severely contract real spending to match the new lower capacity. More people would have starved and died than already have if the Government had have cut back that severely.

But this disaster has nothing much to do with budget deficits as a means to ensure high levels of employment in a growing economy (where capacity grows over time) where the non-government sector also desires to save. A private sector investment boom would have caused the same outcome both in inflation and the political problems of fighting it. So will the hyperventilators also say we should not have net private investment?

The historical context is important to understand because it created the political circumstances which have made the hyperinflation inevitable. But these historical vestiges from the colonial white-rule bear very little relevance to the situation that a modern sophisticated fiat monetary system will face.

Conclusion

So hyperventilate as you like but Zimbabwe does not make a case against the use of continuous budget deficits in defence of full employment.

Bad Governments will wreck any economy if they want to.

A wise government using the fiscal capacity provided to it by a fiat monetary system can engender full employment and equity yet also sustain price stability.

Thanks for the detailed analysis view. It always strikes me that the critics of fiat money who point to Zimbabwe do not also argue for the dissolution of the army and the police force because in oppressive regimes they can be used against the people.

Dear Sean

Yes I agree. Any institution can fail if it is misappropriated by evil idiots. The gold standard monetary system would deliver the same result as the fiat monetary system is delivering in Zimbabwe at present. They could scrap paper money and some other token would hyperinflate.

I actually think the more interesting question is that these things emerge out of state rivalries and chauvanism (in 1920s) and colonial bastardry in Zim’s case. That is much more interesting to examine and come to terms with than trying to blame the monetary system.

best wishes

bill

Thanks for the great analysis. I was waiting for something like this.

Dear Bill –

Thanks for providing a better description of Zimbabwean events I have seen so far coming from non-Zimbabweans.

Some additional facts regarding what pushed Zimbabwe to the brink:

-The collapse of the agric sector led to the closing of other related industries pushing unemployment beyond 80% and output down.

-Tough economic and political climate gave an impetus for those able to migrate out of Zimbabwe to do so.

-In turn the diaspora send money to relatives in Zimbabwe, increasing their purchasing power on a dwindling output base.. contributing also to inflation.

-The central bank (RBZ) was also involved in various Quasi-fiscal activities which pulled the economy into further doldrums.

Now Zimbabwe is almost completely dollarized .. and inflation is in single digits .. the big question is: How can the government regain its power to provide full employment?

Nota

I believe the Rand and Euro are also traded in Zimbabwe, actually don’t they trade just about any currency?

Did ZWE have external debts? I think this had allot to do with the hyperinflation. Making external debt contracts in non-sovereign currencies ( ie hard currencies) .

Dear JC McCutcheon

Yes, Zimbabwe had significant external debts in foreign currencies – the vast majority of it being owed to so-called “official creditors” including multi-lateral creditors (for example, the IMF, the African Development Bank and the World Bank). They were massively in arrears on their debt repayments to the IMF and the World Bank as they were to other external creditors. Most of the debt stock was actually an accumulation of interest owed in arrears to the three organisations I note. This occurred largely because they were forced by these institutions to recapitalise the defaults on their interest payments – so the principal kept growing.

But that doesn’t explain their hyperinflation. That is much more easily understood as the trashing of their capacity to produce real goods and service (drastic reduction in aggregate supply potential). Then, unless mass starvation was the goal, aggregate demand could not be cut fast enough to match the almost 60 per cent reduction in capacity. This is not to say that the government was acting sensibly and humanely. Neither is accurate as far as I can see.

The other point is that in a modern monetary economy a sovereign government should never borrow in a foreign currency. Zimbabwe should have defaulted on all their foreign debt in the same way that Argentina successfully defaulted. That would have included telling the IMF and the World Bank to get lost.

best wishes

bill

It is certainly enlighting that the more you read on Weirmar and Zimbabwe the more that you see it was not a simple case of “printing money” that caused the hyperinflation that is trotted out everytime QE and/or Government deficits are talked about.

I would like your thoughts on instead of privatisation, private/public projects, and bond financing that Governments issue currency to pay for things like the National Broadband Network, the Adelaide-Darwin railway (which was financed via private sector borrowings but the builders of the railway had to sell it because they couldn’t pay their debts), and all the tollways being built in our capital cities.

I think that the current financing of infrastructure adds unnecessary cost. For example, I live in Brisbane. The Gateway Bridge has been a 6 lane bidge since it was built in the early-80s. However, the road at the southern end was only a two lane tar and blue metal (same as a suburban street) road. The about the decade later the state government had to duplicate the road taking it to four lanes, and now they are in the final stages of making it 6/8 lanes for most of it. In between capacity upgrades, there was the upgrade in the road surface to that used on highways. (However, they are also now duplicating the bridge so that there will be 12 lanes feeding onto a 6 lane road – so no doubt in 5-10 years time the state government will probably be announcing a further upgrade). So wouldn’t it be more effective and efficient for all stakeholders (except probably the building contractors) if the Federal Government had currency financed the project and done at all at once – a 6 lane bridge feeding onto a 6 lane road.

Also, what are your thoughts on the Federal Government issuing currency to acquire the infrastructure assets (e.g. Brisbane Port, QR coal hauling business) that the Qld Government has for sale? But then again, the sales would probably not be needed if the Federal Government would currency financed the infrastruture projects that the Qld Government has/will need to borrow to build.

Also, Eric Jansen of itulip.com believes that there will be high inflation in the US, not hyperinflation, for the one of reasons that you outlined above. The GFC has seen credit cut for many businesses, sending them out of business and thus removing productive capacity from the economy and thus seeing the US arriving at point C on your graph.

Great piece Bill

Was Russias “default” in the late 80s a result of debts in a foreign currency?

And when you talk about debts in a foreign currency, how does that occur? As I understand it (or probably misunderstand it) when you sell your goods to another country, you get paid in their currency and then often times turn around and purchase a bond denominated in their currency. Conversely when you buy from someone else it is in your currency and they may turn around and buy a bond form you in your currency. Are their instances where you buy from someone in their currency and then sell a bond in their currency which at a later date you cannot pay? Or are the govts participating in currency markets and making bad trades.

Thanks

Bill,

Finally got around to reading this one – your blog is growing on me…keep up the good work!

How is it that a private sector investment boom generates THE SAME hyperinflationary collapse as failed land reform? You lost me with that one…

Also,

So the land reforms were in my view not well implemented but correctly motivated.

The statement above nicely encapsulates the delta between our respective world views. Things are way easier when the “implement-ees” provide THEIR OWN motivation and are granted a few degrees of freedom. Pharaoh…let my people go! (that one was for alienated)…

Thanks c smith. 🙂

Dear c smith

I hope you stick around and keep talking with us. Diversity is a wonderful thing.

What I actually said was:

But this disaster has nothing much to do with budget deficits as a means to ensure high levels of employment in a growing economy (where capacity grows over time) where the non-government sector also desires to save. A private sector investment boom would have caused the same outcome both in inflation and the political problems of fighting it. So will the hyperventilators also say we should not have net private investment?

This was in the context of the massive supply side contraction brought about by the poorly implemented land reforms. The point was that the growth in nominal demand (from whatever source) was grossly excessive once 60 odd percent of the nation’s productive capacity is gone. So all forms of nominal spending had to be cut severely not just government spending in the short-run. You might argue investment spending adds to capacity and it surely does but after a lag and in the meantime the demand side add would have driven the hyperinflation.

I said: So the land reforms were in my view not well implemented but correctly motivated.

I don’t mind having a different world view on things. In most cases, as a matter of values, I would agree with you that people’s fortunes are best left to their own discretion and management. I am anti-authority (that doesn’t come from within). Have a look at my political compass assessment for a clue.

But what modern monetary theory tells both of us, even if our value sets don’t exactly overlap, is that there are consequences of the government transactions with the non-government sector at the macroeconomic level which constrain what we do at the micro level. So, for example, if there is deficient aggregate demand overall, it doesn’t matter what the “implement-ees” want (say a job) – they are powerless to move the aggregate ration! That is a legitimate role for government to play in ensuring the rations are removed to actually allow the “implement-ees” to implement their destiny.

I also don’t categorise people in terms of their productivity levels – which was an implication of one of your earlier comments in relation to mass unemployment. I rather classify them as “implement-ees” – each one wanting to implement their own destiny and the outcomes being of importance to that particular person and their loved ones and more broadly all of us. I don’t assume your wishes and desires or your children’s hopes etc are subordinate to my own or those of anyone else.

Stay around and keep arguing.

bill

Impressive history recital. Unfortunately, you appear to neglect the natural growth of money supply (M1) – which through its multiples – can more than make up for the savings rate within the private sector. Thus it is not by any means necessary for government spending to make up for aggregate savings.

Indeed, a “deficit” must be created to finance such savings but that deficit can occur in the natural growth of credit to both consumers and the private sector as the money supply expands. And government does not necessarily need to provide any spending inputs to maintain private sector growth. However, money supply growth/contraction is not synchronous in nature with growth/contraction of aggregate savings (at best, plesiochronous.) Due to propagation delays and financial eddy currents, government intervention can – as in not must – help to smooth the wrinkles as it were. However, prop delays due to government intervention tend to be more excessive due to the relative inefficiency of government spending processes. As a result, it is very easy for governments to over-react and create greater perturbations in the economy than might otherwise be experienced if aggregate savings, credit, and interest rates were left to their own devices.

Otherwise, an interesting read.

O.B. Ron Quixote,

As I understand it:

I\’m unsure what you mean by M1, as M1 is defined as government currency plus demand deposits but then you state something akin to the money multiplier process. perhaps I have misunderstood you, but I am going to assume you are referring to bank money.

When a bank issues a loan a matching deposit is created as a matter of account. any deposit which exists without a corresponding loan, is either because of an external account surplus, or due to a government deficit spending. Consider the following simple example:

In a closed economy where the government balances its budget and has no outstanding debt. All deposits which exist, exist as a residual from loan creation, that is, they represent a loan which has not been paid back. At the aggregate level all financial assets must equal financial liabilities and the private sector has not networth and therefore cannot net save.

[O.B. Ron Quixote,

Unfortunately, you appear to neglect the natural growth of money supply (M1) – which through its multiples – can more than make up for the savings rate within the private sector. Thus it is not by any means necessary for government spending to make up for aggregate savings.

As I understand it:

I\’m unsure what you mean by M1, as M1 is defined as government currency plus demand deposits but then you state something akin to the money multiplier process. perhaps I have misunderstood you, but I am going to assume you are referring to bank money.]

I understand it the same way, and I think it’s wrong. Only the government can accommodate a desire to net save by increasing the deficit.

Why is 2% unemployment desirable? Seems a little far fetched to me for a number of reasons.

1. If work is so easily available people will raise their expectations and hold out for better jobs, prolonging the time it takes to find a new job.

2. Technology changes, relocation of industries offshore, and other such changes will mean that many people are left with skills that are no longer in demand, but will be reluctant to start a new job at less pay.

3 + other traditional economic explanations for unemployment.

How do we know 2% is the ‘magic’ number? Is there any period in history where this was acheived?

Anyway, moving along.

You go on to say…

“The non-government sector typically decides (in aggregate) to save a propoportion of the income that is flowing to it. This desire to save motivates spending decisions which result in the flow of spending being less than the income produced. If nothing else happened then firms would reduce output and income would fall (as would employment) and households would find they were unable to achieve their desired saving ratio.”

But private saving rates in Australia recently have been negative. If there is a rising private debt balance isn’t the opposite true?

Anyway, if someone could direct me to a more detailed technical explanation of MMT I would appreciate that.

Cameron

Cameron, there is nothing magic about 2%. All magic is with the last person who want a job getting it. Whether it is at 2% or 20% is irrelevant.

Re negative savings rate you should also include corporate savings into the equation. Anyway consistent negative saving rate is not sustainable. Therefore government should at some point of time intervene and dampen private demand in the area which drives negative savings most (i.e. bubbling).

Russia in 1998 is an example of how much the flat earth economists are wrong in what determines the value of a currency

Russia had a fixed fx rate of 6.45 rubles to the US dollar going into the August crisis.

At the end, rates on gko’s went to over 200% until there was no interest rate where holders of rubles did not want to cash them in at the CB for dollars. Dollar reserves were depleted, and no more dollars could be borrowed to support the currency.

Instead of simply floating the ruble and suspending conversion the CB simply shut down the payments system and the employees all walked out the door.

It was several months before the payments system was restarted.

There was no confidence, no faith, and no expectations of anything good happening.

The ruble went from 6.45 to about 28 or so in what has turned out to be a one time adjustment.

There was no hyper inflation, and not even much inflation as per Bill above, just a one time adjustment.

Pretty much the same for Mexico when it’s fixed fx regime blew up in the mid 90’s. The peso went from about 3.5 to 10 in a one time adjustment.

These are two examples of stress far in excess of whatever the US, Uk, and Japan could possibly face, yet with no actual inflationary consequences, as defined.

http://www.moslerforsenate.com

Your analysis is simplistic and ignores a number of key parts of the collapse of the zimbabwean economy.

Firstly you ignore the impact of the decision made in 1997 to award the War Veterans an unbudgeted compensation package which blew out the fiscus. The only was to fund this was to create money through debt and therefore fuel money supply growth. If you look at the Zimbabwe dollar against the Greenback and the Zimbabwe inflation rate you will see it spikes at this time.

You also fail to deal with the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe’s massive involvement in the Zimbabwe economy from a quasi-fiscal side. The Reserve Bank was essentially printing money hand over fist to fund the loss making parastatals, the newly resettled farmers, and of course the Zanu-PF bigwigs.

That was why the really big hyper-inflation took off after 2005 rather than at the height of the land invasions in the early 2000.

I suggest you read a Zimbabwe economist like John Robertson for a more thorough and correct analysis of the true situation

I just finish watching a program on America’s crumbling infrastructure: roads, bridges, water supply especially in CA and most important the electric grid. The estimate is a 1.5 trillion over five years to bring the grid into the 21st century. Questions: Would this not generate millions of jobs? If I can see this as a benefit to the economic expansion, where are our current political leaders? I have yet to see a political leader from either party speak to the irrelevance of deficits and need to improve infrastructure and the net consequence of such improvement to the economy. How does one go about improving basic economic knowledge?

Barri

Bill,

In your statement: “Inflation is the continous rise in the price level,” you have not dealt with the issue of what actually causes this phenomenon of a rise in the general price level.

There are two side to the price level: 1) a numeraire 2) good or service being priced. In a fiat monetary system such as Zimbabwe was (and remains, only now they have competing fiat currencies), all prices of goods and services are measured in terms of fiat currency, the numeraire. The general price level can only rise when the numeraire loses value relative to those goods and services, i.e. purchasing power. It simply cannot be otherwise. As a central bank and government manage the currency, they alone are responsible for a loss of purchasing power of their fiat currency. This is why the function of protecting the value of the currency is enshrined as the role of central banks in most constitutions.

The Zim$ lost value as the Mugabe government monetised the fiscal deficit and to settle external debts to the likes of the IMF. This led to a rapid depreciation of the Zim$ relative to goods and services, particularly as the supply of goods and services dried up in the local economy owing to govt regulation, and as the currency was overvalued on Zim foreign exchange markets, meaning foreigners would not accept in payment Zim$ for their goods and services.

With the US announcing today it will print another $600bn over 6 months and use $300bn in proceeds of maturing MBS’ to buy Treasury debt, it means over 6 months the Fed will monetise nearly the entire CBO-projected US fiscal deficit of $1.1 trillion for 2011. It is absurd and the path Zimbabwe embarked on in the early noughties.

Sure, a ‘wise’ government can manage a currency, but historically ‘wise’ governments such as that of the US can turn decidedly ‘stupid’ in a very short space of time. This is the risk of a fiat monetary system. Always has been, and always will be, and is the reason no fiat currency has ever survived.

Regards, Chris

Dear Gosman:

I frequently re-read this particular blog to refresh my understanding of hyperinflation episodes. I re-read it after reading this discussion, http://www.shadowstats.com/article/hyperinflation-2010, which provides little insight as to mechanisms, other than to caution against “printing money.”

I followed up your reference to John Robertson with his Synopsis of the Zimbabwe situation presented at a conference in Leipzig in May or June, 2009, http://odettejohnrobertson.blogspot.com/2009/06/from-john-robertson.html. The loss of agricultural productivity, as a result of the Land Reforms, is the entire focus of his discussion, and the solution being to re-establish productivity to feed the domestic population. He does not mention the currency, or government printing presses or central banks.

His views seem to support the analysis presented by Dr. Mitchell in this blog. Your points seem to be secondary events; obviously “inflation” of the currency cannot occur if the government simply stops printing it and it ceases to exist. But then prices for food in USD ( or whatever money circulates) would go up as those few with some USD bid up prices for the limited food available. It seems that some sort of inflation will always occur if essential products are in very limited supply.

I still find Dr. Mitchell’s analysis to be the most compelling and insightful I have found yet.

I await his textbook with great anticipation.

In the same way we can imagine that the government burns all money collected as taxes and spends money out of thin air, we can also imagine that they burn all money collected from bond sales. The selling of a bond is like collecting a tax and then later creating money out of thin air and giving it to the people you taxed as a stimulus. While the bond is out it reduces demand like taxes do.

Do you agree that my explanation of bonds is in the MMT spirit? Are there other MMT people who have explained it this way?

I think this means that if bond sales slow to below the rate bonds are being issued that there will be demand released that is inflationary. In fact, if bond sales get really bad it could lead to hyperinflation.

@Vincent ~

This would only be true if bonds were issued only on a hold-to-maturity basis. Since they are not (and cannot effectively be), they can be exchanged as if they were cash with anyone who would accept them in liu of cash for whatever goods or services were being provided. Bonds are effectively currency that pays interest for a certain period, while currency is effectively bonds that pay zero interest. But for the interest, they are identical.

Bill — I wish you had time to answer all the questions — the ones which have answers, that is.

I’m new to MMT but not to Chartalism. Thanks for the explanation from your perspective of Zimbabwe. It is very helpful to clarify the MMT position.

Would you explain each of the Latin American hyperinflations with reference to each of their idiosyncrasies, or is there a unifying theme to which you could point?

Also, would it be too crude to ask whether the main distinction between MMT and Chartalism is that MMT tries to build policy on the back of the observations of Chartalism? To a newby, these policies appear to have at their root the choice of expediency over equity (to use Keynes’ turn of phrase).

Some unifying themes, I think, in Latin American inflation – foreign denominated debt, widespread indexation, high interest rates which serve to inflate rather than disinflate. Unemployment, dependence on imports rather than native industry, weak tax systems are others.

Distinctions between Chartalism, Keynesianism & MMT depends on how you like to lump or split. To me, they are the same thing, the same discipline, monetary economics, as it has developed through time.

Don’t know where or in what regard Keynes opposed expediency to equity. MMT / Keynesian policies, above all the JG, are both. They’re expedient because they are equitable. Full employment is equitable to the debtor, while price stability is equitable to the creditor. The austerity of modern mainstream economics, with the commodity theory of money at its heart, inequitably & inexpediently causes mass unemployment for no reason at all, destroys titanic quantities of real wealth.

Chris says:

“The general price level can only rise when the numeraire loses value relative to those goods and services, i.e. purchasing power. It simply cannot be otherwise.”

This is NOT true.

Cost-push inflation is one example that contradicts your assertion.

MMT

modern monetary theory

ABC News

https://youtu.be/-1Yw4jdkQL4

Bill,

After the collapse of the Weimar Republic and the Nazi takeover, Germany rearmed at a galloping pace, which meant an increase of industrial capacity and efficiency and the restoration of full employment. The pre war years saw Germany going from hyperinflation and dire poverty to readiness for a war that gave European powers and America a six year-long real headache. In the meantime Germany led the way in some of the military technologies that defined the second half of the century.

Can this transformation be taken as a good (good as in illustrative, not in the aims) example of the capability of the fiscal sovereignty you talk about?

Land redistribution, for political reasons, was not well managed. It was obvious in the 1970s that the unequal distribution of land was a major cause of the civil war, probably the major cause. A fellow officer had a theory in 1979 that he could solve the political problem by giving every soldier, of whatever side, 10 ha of state land or APA in exchange for a modern automatic weapon. I disliked him and failed to look at it seriously. I now think he was right. The question was whether there was enough land available without serious confiscations.