I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Japan … just wait … your days are numbered

I was reading this IMF working paper today – The Outlook for Financing Japan’s Public Debt – which was released in January and was on my pile of things to catch up on. The paper is now being used by journalists to predict doom in the coming years for the Land of the Rising Sun. As I note, the stark deviation of the Japanese experience with the predictions of the mainstream macroeconomics models has given the conservatives a headache. As an attempt to reassert their relevance to the debate, the mainstream commentators are inventing new ploys so that they can say – yes we agree that the facts in the short-run don’t accord with our models but brothers and sisters just wait for what is around the corner. My assessment is that they have been saying this for 20 years already. In 5 more years, they will still be disappointed and still prophesying doom. They are pathetic!

Anyway back to the IMF paper. It opens with the excellent comment that must astound those commentators who mindlessly rehearse the mainstream macroeconomic textbook mantras that they poach out of Mankiw and other sources.

… Since the early 1990s, JGB yields and fiscal variables, such as public debt and the deficits do not appear to be linked. During the 1990s the 10-year Japanese Government Bond (JGB) yields declined steadily from 7 percent to below 2 percent, while net public rose from 20 percent of GDP to 60 percent of GDP. Since 2000, net public debt has further climbed to 90 percent of GDP, while long term yields have remained fairly stable at below 2 percent …

More recently, fiscal deficits have again widened sharply, reflecting both discretionary measures and automatic stabilizers in response to the global slowdown. JGB yields picked up in early 2009 following announcements of a series of stimulus packages, but they still remain low by historical standard. With the general government deficit projected to stay around 10 percent of GDP in 2010, public debt will exceed 110 percent of GDP in net terms (225 percent of GDP in gross terms) – the highest among advanced economies.

As an editor I would advise the author to change “do not appear to be linked” in the first sentence to the more accurate “are not linked in any way”.

Japan is the second largest (still) economy in the World. It runs a fiat monetary system like most nations since 1971. Its central bank’s operations are very similar to the operations in most nations. Fiscal policy in Japan is implemented in a similar way to most nations in the World. So it is not some special case although it does have some distinctive cultural features and one important institutional difference relating to the absence of public retirement pension plans and an emphasis on private or corporate provision.

Anyway, the debate about the relatively large Japanese public debt ratios is quite interesting. In a recent Economist article (published April 8, 2010) – Sleepwalking towards disaster – we read:

FOR years foreign observers gave warning that Japan’s combination of economic stagnation and rising public debt was unsustainable. Over the past two decades the country has stumbled in and out of deflation, slipped down the global league tables on many social indicators and amassed the largest gross public debt-to-GDP ratio in the world (a whopping 190%). Yet government-bond yields have remained stubbornly low and living standards, by and large, are high. Visit the country and you will see no outward sign of crisis. Politicians and policymakers have bickered and schemed, but have mostly chosen to leave things as they are.

That cannot go on much longer. The figures are getting worse. Japan urgently needs radical policies to tackle the problems, and new leaders to implement them.

The point is that economists etc have been lining up with predictions of a Japanese apocalypse as the budget deficits persisted, interest rates stayed at zero, long-term rates were similarly very low and stable and inflation fell and at times deflation was the issue. If we had the inclination (and I could go back through my press cuttings and assemble quotable quotes over the years) we would be able to produce a time series of predictions of disaster from all the major economists who comment on Japan.

Year-in, year-out they have been peddling the same line. And we waited patiently.

Those of us who work within the framework provided by Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) have never predicted a meltdown in Japan. It all made sense within the stock-flow consistent monetary framework that is one of the basic building blocks of MMT.

In the early 1990s, there was a major collapse in private spending in Japan, a nation already committed for cultural and institutional reasons to a high private saving rate. The collapse followed the bursting of a very large property price boom. Japan then entered its lost decade.

The Japanese government was overly cautious with respect to the provision of fiscal policy stimulus. They initially adopted an expansionary role which delivered modest real GDP growth. But, over this period they were constantly harassed by the deficit-terrorists and in 1997 succumbed to the pressure and introduced a contractionary budget. The economy, which was showing some signs of recovery given the fiscal support, nose-dived.

This led to the period of expansionary monetary policy. Over most of this period the Bank of Japan (BOJ) ran two distinctive policies: (a) its zero-interest-rate policy (ZIRP) which began in February 1999 – in its official statements the BOJ said it would maintain the call rate (the short-term policy rate) at zero until deflationary concerns are dispelled” (Source: BOJ Statement April 1999); and (b) a policy of quantitative easing which saw the BOJ from March 2001 adding bank reserves in excess (by a large margin) of the volume needed to ensure its liquidity management operations could maintain the zero policy rate.

The ZIRP policy wasn’t consistent and in some periods the call rate was allowed to rise to 0.25 of a percent but mostly it was held at zero. The BOJ has consistently told the financial markets that the ZIRP would only be relaxed when the annual core inflation rate has “been positive for several months and, moreover, is expected to remain positive”.

Researchers have studied whether the ZIRP actually impacted on the term structure. A number of poor mainstream studies tried to deny the impact and instead said the long-term rates were just a function of the deflation and would spike up at any time if growth was expected. They were wrong – as usual.

In 2004, the Bank of International Settlements held a conference in Switzerland on the theme – Understanding Low Inflation and Deflation. One paper presented at the Conference – Japan’s deflation, problems in the financial system and monetary policy – by Naohiko Baba, Shinichi Nishioka, Nobuyuki Oda, Masaaki Shirakawa, Kazuo Ueda and Hiroshi Ugai (hereafter Baba et al) – examined several features of the Japanese monetary policy.

Contrary to earlier studies, the authors found that the ZIRP had:

… significant effects on the term structure of interest rates

Further, in relation to the quantitative easing (QE) the authors find that the aim was to maintain “ample liquidity supply by using the current account balances (CABs) at the BOJ as the operating policy target and the commitment to maintain ample liquidity provision until the rate of change in the core CPI becomes positive on a sustained basis”. The CABs are the central bank reserves held by the commercial banks.

To give you an idea of how significant the QE was in volume, Baba et al note that the BOJs commitment to a liquidity target on the CABs was:

… raised several times, reaching ¥ 30-35 trillion in January 2004, compared to the required reserves of approximately ¥ 6 trillion.

So to maintain the stable zero interest rate the BOJ just had to leave around 6 trillion yen in the system but instead within 3 years of the policy beginning had added almost 6 times that volume.

Two things to note about this. First, the growth in the bank reserves (base money) did not generate anything like a proportional increase in the broader monetary aggregates. MMT teaches you that increasing bank reserves does not increase the ability of the private banks to lend (create credit). This is a myth that mainstream macroeconomics textbooks perpetuates.

Second, the rather significant increase in bank reserves in Japan did not push up inflation which remained persistently wedded to crawling along the horizontal axis (that is, at zero) and occasionally cutting it into the negative orthant. Again this defied mainstream macroeconomics predictions. However, from a MMT perspective it was to be expected.

Please read the following blogs – Building bank reserves will not expand credit and Building bank reserves is not inflationary – for further discussion on this point.

The Japanese government also reintroduced fiscal stimulus after the 1997 catastrophe. The evidence suggests that it was this move that promoted real GDP growth in the subsequent period which persisted weakly until the recent crisis. The evidence also suggests that the monetary policy interventions were less effective for the reasons I explain in the two blogs noted in the last paragraph.

Baba et al make an interesting observation on Japanese fiscal policy:

Aggressive fiscal policy supported by aggressive monetary expansion could function as a powerful weapon to fight deflation. In a sense, the BOJ has partially provided such a framework by maintaining a near-zero short-term interest rate for almost 10 years. The fiscal authority, however, has stopped shy of exploiting this environment, as can be seen by sharp reductions in public investment since 1996.

So if they had have been more aggressive earlier and consistently so, the lost decade might have been just a drawn out recession and they would have resumed robust growth much earlier than they did.

As a result of the obvious facts – rising public deficits, rising public debt ratios, low interest rates and deflation – the mainstream commentators are stuck for words. It has been interesting watching the way they have attempted to reimpose themselves upon the debate. The Economist quote above gives you an inkling. But the IMF paper I referred to at the outset refines the attempt.

The task to be sure is to concede the facts – plead special circumstances – and then reassert the mainstream claims about rising interest rates and inflation risk by appealing to certain “trends”.

The IMF paper argues that the:

… factors behind the low and steady JGB yields, including Japan’s large and growing pool of household savings, stable institutional investors, and strong home bias … are likely to persist helping to keep down JGB yields, but that over time, the market’s capacity to absorb public debt will likely diminish as population aging reduces savings inflows and financial reforms enhance risk appetite … but over a longer-horizon, fiscal consolidation will become critical for ensuring the smooth financing of government operations.

So despite the mainstream claim that “expansionary fiscal policy has a positive effect on government bond yields” the Japanese economy doesn’t validate that conjecture. But eventually when these “trends” assert themselves it will become consistent with the mainstream theory – that is the line we are being sold in this paper.

The empirical work presented in the IMF paper “point to a weaker impact of the primary deficit on JGB yields” which is also “statistically insignificant”. For non-econometricians out there that means there is no impact. The coefficient on the relationship is not different to zero!

Even when you control for JGBs held by the BOJ or use high-frequency data the “overall impact of primary deficits on JGB yields is close to zero”.

The reasons given by the IMF paper are now well known. There is a large pool of household assets so that “Japan had enjoyed relatively high household saving rates (over 10 percent) until around 1999 when they began to decline sharply. High savings were typically attributed to various factors, such as the seniority wage system, the existence of sizeable bonuses, rapid growth, and sluggishness of consumption (habits).”

So households like to manifest their saving by purchasing risk-free JGBs.

There is a “(s)trong home bias … JGBs have been financed largely by domestic investors (94 percent of holdings as of end-2008), who may exhibit more stable behavior than foreign investors”.

It is clear that the household sector does not like risky speculation in Japan. Perhaps this is because they have enjoyed strong support by governments (and firms) for maintaining low unemployment and underemployment.

Finally, there are several “large and stable institutional holders” in Japan that purchase JGBs. “The Japan Post Bank (previously the postal savings) and the Government Pension Investment Fund have invested … around 35 percent of the total JGBs”. Further the BOJ holds large stocks of JGBs.

However, according to the IMF paper all of this is about to change and make “yields more sensitive to the debt level as standard theory predicts”.

The Economist article noted above expresses it this way:

There are three big reasons why the crisis in Japan’s public finances will eventually come to a head. The first concerns government bonds. The state has for years relied on domestic savers to buy them. But as Japan’s people age and run down their savings, they will have less money to invest in government bonds … Japan might then have to rely on foreigners to finance its debt, and they will want much higher returns. That will, at the very least, provide an acute reality check. Goldman Sachs says some foreign investors are already positioning themselves for a “meltdown”.

Another Economist magazine article published on April 8, 2010 – Japan’s debt-ridden economy – clarified the Goldman strategy:

They were buying options to prepare for two related events: a sharp rise in long-term interest rates because of an erosion in debt sustainability, and a slump in the yen caused by capital flight from Japan

So the basic argument thus being rehearsed is that ageing population is now dis-saving and consumption rates are rising. So the household sector will over time demand less JGBs which “could also affect the market capacity to absorb public debt”.

It is so patently ridiculous that I was laughing when I read it. Can’t these characters invoke a bit more guile than this in their pathetic attempts to reinstate their credibility in relation to Japan?

Note that the BOJ holds large stocks of JGBs. They could easily hold more and more! The low yields will persist even if the household sector and the big pension funds and post bank take a declining proportion.

Would this matter? Not a single bit.

Further, given that the Japanese government is a fiat-currency issuing body operating in a flexible exchange rate environment the debt-issuance is voluntary anyway. So if things started to get ugly with respect to its access to investors they could simply take the first step into the post-1971 reality and stop issuing debt. New arrangements with the central bank could then be introduced within the legal framework to account for the net spending without the accompanying reserve drain.

This would not increase or reduce the inflation risk associated with a growing economy. But in the Japanese case, inflation is hardly going to be a problem the government will have to deal with.

Finally, the increased domestic consumption will stimulate the local economy and reduce the public deficits anyway. The government could assist this process by increasing basic pensions and introducing a Job Guarantee to absorb the unemployed who live in public parks and rely on charity organisations for food.

As an aside, the Japanese government would be doing the world a service if they thwarted the speculative positions taken against it by GS!

The IMF paper doesn’t understand any of this because they are still operating with macroeconomic models based on gold-standard/convertible currency logic. Their solution is predictable:

Over the medium term, it is critical to establish a credible framework for ensuring fiscal sustainability. The framework will need to feature a clear timetable for comprehensive tax and expenditure reforms to be implemented once the economy recovers.

The fiscal sustainability term is now being used by all these commentators with nothing added to give it any meaning. It is “as if” we know what it means. So we are beguiled into loose thinking about austerity, public spending cuts etc without the slightest understanding of what this would mean.

These discussions about fiscal sustainability never provide a stock-flow consistent macroeconomic framework which would allow us to follow through on the consequences of some of the “comprehensive tax and expenditure reforms”.

Please read this suite of blogs – Fiscal sustainability 101 – Part 1 – Fiscal sustainability 101 – Part 2 – Fiscal sustainability 101 – Part 3 – to see what fiscal sustainability really means.

The April 8, 2010, Economist magazine article, in its desperation to be relevant, goes even further than the IMF proposals:

What’s more, rising social-security payments as the population ages are likely to put even more pressure on public financing, while the shrinking workforce will mean even slower growth and smaller tax revenues. In 1990 almost six people of working age supported each retiree. By 2025 the Japanese government expects that ratio to fall to two. At some point Japan may have no other option than a domestic default in which the older generation, who hold most of the government bonds, will see the value of their investments cut to reduce the pressure on the younger generation. Such an intergenerational transfer would come at enormous political and social cost, not least in a society with such a strong sense of communal well-being.

And such an intergenerational transfer will never occur. The Japanese government are smart enough to realise they have all the cards. They issue the currency. They will always be able to service the JGB payments. The only problem facing Japan is whether there will be enough real resources available to provide a rising standard of living to their citizens of all ages. If there are then the Japanese government will be able to provide them in lieu of private provision.

There is no financial constraint facing the government and the idea of it having “no other option than a domestic default” is a pathetic attempt to capture the readers’ interest.

You might like to read these blogs – US federal reserve governor is part of the problem – The US should have universal public health care – Another intergenerational report – another waste of time – Democracy, accountability and more intergenerational nonsense – for further discussion about the intergenerational debate.

Australia heading for an out of control real estate bubble

Not!

This little digression, continues my theme exposing those commentators (and central bankers), who have in in recent months been talking up the proposition that our economy is about to overheat and the first signs are in the emerging real estate price bubble. For readers from abroad, this has occupied many column inches in recent months.

While continuing its obsession for putting up interest rates despite 12.8 per cent of the available labour resources being underutilised (either unemployed or underemployed), the RBA said in its decision statement last week that:

Credit for housing has been expanding at a solid pace.

This was one of the major reasons for the further hike in interest rates. Well it is untrue! Unambiguously so. These NAIRU-merchants lie just to ensure they can get control of the policy agenda again having lost it to the more effective fiscal interventions at the height of the crisis.

Yesterday, the ABS released its Housing Finance data for February and it showed that:

The number of owner occupied housing commitments (trend) fell 4.0% (down 2,138) in February 2010 compared with January 2010. Decreases were recorded in commitments for the purchase of established dwellings excluding refinancing (down 1,478, 4.9%), the refinancing of established dwellings (down 378, 2.7%), the construction of dwellings (down 196, 2.8%) and the purchase of new dwellings (down 86, 3.8%).

Here is a comment from a bank economist (one of the rare times I agree with their assessment – but when several months of data is staring you in the face!):

House credit growth is not, as the bank would have us believe, solid. That is simply not true and, more to the point, the bank has said previously that house price growth isn’t a problem unless accompanied by a build-up in leverage. This argues for a softer rate hike touch.

Today the Australian Bureau of Statistics released its Lending Finance, Australia data for February, which provides a more general view of credit conditions in the economy. Guess what?

Housing finance for owner occupiers fell by 4.4 per cent in the last month. Total personal finance commitments decreased 0.3 per cent (trend) and the “trend series for the value of total commercial finance commitments decreased 0.4%”.

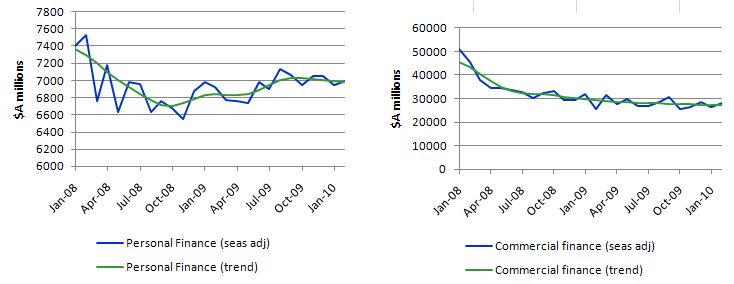

The following graph shows the seasonally-adjusted (blue lines) and trend estimates (green lines) for total personal finance and total commercial finance in $A millions from January 2008 (the month before the crisis emerged in Australia) to February 2010. You can tell the story yourselves. Pretty clear and somewhat contrary to what the RBA is trying to spin as it seeks to justify its irresponsible interest rate hikes at present.

Another bank economist joined the throng (Source):

Over all it highlights the weak environment that we’re in. It’s not a guaranteed recovery that we’re in.

In case it wasn’t obvious, the Australian so-called “growth miracle” has been driven by the fiscal stimulus not the “mining boom”. The fiscal stimulus is being withdrawn – far too early – and the strength of private demand is there for all to see – tepid at best.

If the US economy stalls which is possible and China stalls – the latest figures from China are not encouraging (I will write about them another day) – then our cosy, smug “get back into budget surplus” obsessed government will have undone all the work they did in preventing the recession. Together with the equally smug RBA our macroeconomic policy is not well balanced or targeted at the present.

Coming up

A Fiscal Sustainability “Teach-in” Counter-Conference looks like happening in Washington DC on Wednesday, April 28, 2010. Why there and then?

Well the Peter G. Peterson Foundation is one of the places deficit terrorists hang out and it is sponsoring a “Fiscal Summit” in Washington, DC on that day to discuss fiscal responsibility and fiscal sustainability. The cast of speakers is a disgrace. All of them mainstream naysayers. Very little meaningful dialogue will come out of this meeting but because of their influence the outcomes that do emerge may impact badly on policy.

To counter this bias in the public debate a MMT alternative was initially proposed by Joe Firestone. It is a great initiative. He is now being supported by a bevy of helpers who are working to make it a reality.

I am very privileged to have been invited as one of the key speakers and if things turn out I will report from there the week after next. If you can come down to the US Capital for the day it would also be an excellent way of showing support for an alternative view of the policy and the opportunities the fiat monetary system offers governments desiring to advance public purpose.

The way forward is for people-based movements to counter the biases that are imposed on policy by the bankers and their cronies. Events like the “Teach-in” are essential parts of that mobilisation. The Teach-in movement goes back to the Vietnam War days and were effective vehicles for ultimately ending US involvement in that hideous invasion.

I will post more updates as the event format and location etc become clearer.

Also coming up

I have also been reading the report released yesterday by the Iceland Truth Commission. I might have something to say about this very interesting analysis in due course.

That is enough for today!

That is fine but what about The number of non owner-occupied housing commitments?

In Japan – would it be over-simplistic to say that people are simply ‘banking with the Government’ rather than ‘banking with the banks’? Monies that were once saved horizontally are being saved vertically.

If an increasing proportion of loans made by banks are not being redeposited back in the private banking system but, instead, are used to buy government bonds would this not have an effect similar to what is being witnessed?

If the governments are going to bail the banks out regardless and people do not trust the banks any way, it might makes things quicker to miss out the banks entirely.

Dear Senexx

Value of dwelling commitments (% change January 2010 to February 2010):

— Total dwellings -3.4 per cent

— Owner occupied housing -4.4 per cent

— Investment housing -1.1 per cent

Number of dwelling commitments (% change January 2010 to February 2010):

— Owner-occupied housing -1.8 per cent

— Construction of dwellings -3.0 per cent

— Purchase of new dwellings +0.7 per cent

— Purchase of established dwellings -1.8 per cent

Do you have a point to make?

best wishes

bill

Billy, I would have thought that a reduction in debt would have a good thing given that mortgage debt to GDP ratio is sitting at 85% and rising. Our personal debt levels are appalling. Looking at your graph, personal finance is only off $400m from it\’s Jan 08 high. Over $7 billion, it\’s bugger all really. The scary graph is the commercial lending that is down over $2 billion. It seems that job producing debt is slowly declining (explains the high underutilisation rate – can\’t get a decent job) while those who are still employed are gorging on all sorts of consumer crap (explains the high underutilisation rate – have to work in retail). Perhaps the reduction in housing finance is nothing more sinister than people simply saying \”I\’m not going to pay that sort of money\”. If interest rate rises has forced people to live within their means, then in the long term, this has to be a good thing. Given that interest rate rises has tempered the consumer credit binge surely has to be a good thing given the high debt levels the nation is a proud owner of, it\’s just a shame about the collateral damage.

Dear Glen

I agree with you but the aggregate demand space left by the decline in private spending has to be filled. That is why attempts to cut the federal deficit are very ill advised.

best wishes

bill

Fuguez,

private savings with the banks end up in the government as the result of interest rate policy. Cash balances of private sector are somehow a good proxy of bank reserves which are absorbed in the OMO operations of the central bank.

On the other hand, access to government bonds aligns risk-less income opportunities of financial and non-financial parts of private sector.

You might say that private sector “banks” directly with the government but this sounds to me like a needless and semantic complication of reality

For Joe Firestone or coordinator of counter-Peterson conference that you

are trying to put together for end of April that Prof Mitchell refers to above:

Please contact me I’m in the DC area and may perhaps be able to donate some

services for the Conference for you to avoid some costs if the budget

is tight.

Resp, Matt Franko, matt_franko@mac.com

New word for today.

Look up: orthant

orthant

generally,for a n-dimensional distribution the probabilities of individuals falling into the 2n orthants into which the sample space is divided by the co-ordinate planes Category: Mathematics

Found on http://www.mijnwoordenboek.nl/definition

Orthant

In geometry, a closed `orthant` is one of the 2`n` subsets of an `n`-dimensional Euclidean space defined by constraining each Cartesian coordinate axis to be nonnegative or nonpositive. That is, a closed orthant is the analogue of a closed quadrant in the plane and a closed octant in three-dimensional space. A closed orthant is defined by a system of inequalities :ε`i“x“i` ≥ 0 for 1 ≤ `i` ≤ `n` on the coordinates `x“i`, wher…

Found on http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Orthant

Dont know how I am going to fit this in to a conversation today but I will try.

On Topic. I am confused in regard to how Japan can stimulate its economy from here. Agreed the debt is not a problem at all as it is domestic and Japan can print as much money as it likes. But how do you get consumption up so that when the stimulus fades away the real long term domestic demand keeps everyone employed. The Gov cant just keep building Schools and bridges forever can it? What did I miss?

Last mile update!!!!

Mark Thoma just posted an article written by MMTer Rebecca Wilder. http://economistsview.typepad.com/economistsview/2010/04/deficit-hysteria-is-now-mainstream-thinking.html#comments

Bill, apparently not because I expected Investment Housing to be rising.

Dear Bill,

Have you or some of your MMT colleagues – pioneers advised the Japanese government in their economic decision making? Or the Japanese government were just some of billy blog regulars? 🙂

Bill,

About : “If we had the inclination (and I could go back through my press cuttings and assemble quotable quotes over the years) we would be able to produce a time series of predictions of disaster from all the major economists who comment on Japan.”

That would make for interesting epistemological study… if you have the chance, please, I’m a taker.

Lucky Punch,

I think you are wrong about this:

“Agreed the debt is not a problem at all as it is domestic and Japan can print as much money as it likes.”

because the debt need not have to be domestic to be safe. It’s a common misconception, and wished Bill had insisted a bit more on this. Is there another post pertaining to that issue?

Bill and everyone else following,

“Note that the BOJ holds large stocks of JGBs. They could easily hold more and more! The low yields will persist even if the household sector and the big pension funds and post bank take a declining proportion. Would this matter? Not a single bit.”

I sense that there is a bit of gap here either in the explanation or, more likely, in my understanding.

Why did the BOJ accumulate the JGBs in the first place? My recollection is that buying treasury bonds is the primary operation by which a central bank supplies liquidity (reserves) to the interbank market. In fact, the opposite is likely to happen when the government runs a deficit : treasury bonds are sold by the central bank to offset the increase in reserve resulting from the deficit.

Please, some clarification would be highly appreciated.

“Further, given that the Japanese government is a fiat-currency issuing body operating in a flexible exchange rate environment the debt-issuance is voluntary anyway. So if things started to get ugly with respect to its access to investors they could simply take the first step into the post-1971 reality and stop issuing debt. ”

I take it, this is *in part* what the BOJ has been doing as part of QE. Specificaly, the “BOJ raised several times, reaching ¥ 30-35 trillion in January 2004, compared to the required reserves of approximately ¥ 6 trillion. “. In interpret it as : Less than 100% deficits were matched by issuance of debt. Am I right?

“About : “If we had the inclination (and I could go back through my press cuttings and assemble quotable quotes over the years) we would be able to produce a time series of predictions of disaster from all the major economists who comment on Japan.”

That would make for interesting epistemological study… if you have the chance, please, I’m a taker.”

Well, I’m still a taker, and found one, so thought I’d start posting them here, for the record, when I bump into one:

“The balance sheet of a central bank, like that of any other entity in the monetary economy, has to consist not only of assets and liabilities but also of a surplus of the former over the latter. With this own capital or equity it safeguards itself against the threat of bankruptcy. Only because economists have forgotten this old wisdom, dubious recommendations, most prominently by Paul Krugman, were made in recent years to the Bank of Japan to salvage the deflation-ridden Japanese economy by engaging in large scale purchase of long-term government debt. The idea that such a policy will lift bond prices and lower short-term interest rates and, thereby, trigger an upswing, does not take into account that this could bankrupt the Bank. The more this policy succeeds in dispelling deflation and the more the economy prospers, the higher long-term interest rates will be. This increase in yield will decrease the value of the bonds held by the Bank of Japan: “If the Bank held only 10 percent of the long-term government bonds outstanding and interest rates rose by two percentage points, the resulting losses would wipe out the institution’s entire capital and reserves” (Lerrick, 2001, 13).”

THE EUROSYSTEM AND THE ART OF CENTRAL BANKING*

by Gunnar Heinsohn and Otto Steiger

Paper to be presented at the 19èmes Journées Internationales d’Economie Monétaires et Bancaires, Lyon, 6 et 7 juin 2002.

Bx12 says: Tuesday, May 18, 2010 at 13:11…continued

“It is true that in a liquidity crisis of a counterparty of the central bank the latter usually does not have the time to check whether the former is solvent or insolvent…After the terror attacks of 11 September 2001 the Federal Reserve Bank of New York did not even have time to round up a defensive line of commercial banks. Instead it swung its discount window wide open because Wall Street was closed and the money markets barely functioned. In regular times the weekly total lent through the discount window is a mere $ 200 million. Yet, within a day of the New York Bank’s announcement that the window is open to provide liquidity, it received demands for $ 46.25 billion in one-day funds. It effectively lent $ 38.25 billion (Ip et al. 2001, 6).

In this case, all the risk of loosing its equity was with the New York Bank. Yet, it was clear that in the worst case the Treasury would refund the Bank with tax-payers’ money to keep it operating because a central bank cannot create money out of nothing, as many an economist believes, but risks its equity when it creates money. Thus, the Ministry of Finance forms the final defensive line for a central bank’s function as lender of last resort (cf. Goodhart, 2000b, 11 f.; Schoenmaker, 2000, 220-222).”

This line of reasoning, that Treasury ultimately serves as the lender of last resort/backing of the CB because of its ability to tax is shared, seemingly, by Willem Buiter.

So, what would happen in operational terms, if equity was swallowed up in a time of crisis as above?