With a national election approaching in Japan (February 8, 2026), there has been a lot…

Britain can easily increase military expenditure while increasing ODA to honour its international obligations

It is hard to keep track of the major shifts in world politics that are going on at the moment. I am in the camp that saw the extraordinary confrontation between Trump/Vance and Zelensky as demonstrating how embarrassing the US leadership has become. I am not a Zelensky supporter by any means but the behaviour of the US leadership was beyond the pale as it has been since January. I am no expert on geopolitical matters but it seems obvious to me that the US is now opening the door further for China to become the dominant nation in the world as the US sinks further into the hole and obsesses about who should thank them. And the latest shifts are once again going to demonstrate how dysfunctional the EU architecture has become. If it is rise to the post NATO challenge then its obsession with fiscal rules will have to end and they will have to work harder to create a true federation. I am skeptical. The shifts are also once again demonstrating that mainstream economic thinking is dangerous, something I can claim expertise to discuss. The recent decision by the US Administration to hack into the USAid office is probably not the definitive example of this point because it is more about being bloody minded than ‘saving’ money. It will just further open the door for China though. However, the decision by the UK Labour government to reduce Overseas Development Assistance (ODA) to (according to Starmer/Reeves logic) ‘pay’ for a rather dramatic increase in military expenditure is a classic example of how policy goes astray when mainstream economic thinking in general, and the British fiscal rules, specifically are used to guide policy.

I have previously covered the ODA issue in these blog posts among others:

1. Myopic meanness – Australia’s ODA cuts to its neighbours in the Pacific (April 5, 2022)

2. Advanced nations must increase their foreign aid (April 7, 2021).

3. Australia’s Overseas Aid cuts reveal a nation that has lost its spirit (May 15, 2017).

4. Australians have plenty of reasons to be ashamed – ODA is one of them (December 29, 2016).

5. Australia’s generosity to other nations is collapsing (April 9, 2015).

ODA goals

There are countless examples from the last several decades where privatisation, outsourcing, funding cuts, imposing so-called ‘contestability’, etc has produced poor outcomes for citizens while not achieving the ‘stated’ goals.

I say ‘stated’ because of course what politicians claim is the goal and what they really want to achieve are often two different things.

I am sure that Trump and Vance set out from the outset over the weekend to assemble the media in the Oval Office in order to humiliate Zelensky.

It was nothing to do with peace but rather was probably to set the cat among the Europeans, who Trump has been criticising for some years for not spending enough on the defense of their own borders.

Zelensky was installed by the Americans in the first place and is once again being manipulated to serve US ends, which are now clearly different.

Back to the story – the announced cuts in foreign aid are another example of policies using false logic.

In 1970, the 25th Session of the General Assembly of the United Nations passed Resolution A/RES/2626(XXV) – and Paragraph 43 stated that::

… Each economically advanced country will progressively increase its official development assistance to the developing countries and will exert its best efforts to reach a minimum net amount of 0.7 percent of its gross national product at market prices by the middle of the decade.

The commitment was not met by many advanced nations, including Australia.

Thirty-two years later the UN reaffirmed the goals – Report of the International Conference on Financing for Development – at the Monterrey meetings (March 18-22, 2002) stating:

… we urge developed countries that have not done so to make concrete efforts towards the target of 0.7 per cent of gross national product (GNP) as ODA to developing countries …

The – The 0.7% ODA/GNI target – a history – is worth reading (short).

The ODA/GNI ratio tells us how much the government of any country is allocating to ODA relative to the size of the economy (the nation’s total income).

The latest OECD – Development Co-operation Report 2024 – notes that:

We feared the worst and yet the recent data on poverty has hit hard. Thirty years of progress in eradicating extreme poverty have been derailed by the Covid-19 pandemic, ensuing economic shocks and debt distress, by war and conflict, and, as predicted, by the serious effects of climate change.

Depending on who counts and how, between 700 million and 2 billion people live in extreme, absolute or multidimensional poverty in low- and middle-income countries …

Now is the time to address these issues, before these goals become harder and more costly to reach in the face of impacts of climate-induced extreme weather, shifting agriculture patterns, rising sea levels, and potential mass migration between and within countries.

The Report also noted that “Less than one of every ten US dollars, or 9.5%, of Development Assistance Committee (DAC) members’ bilateral official development assistance went to grants for poverty-reducing sectors in 2022”.

And that share has been declining (“However, the trend indicates a decline in ODA to LDCs since 2020, suggesting a diminishing focus on pro-poor allocation in recent years (2020-22)”)

Wealthy nations are increasingly abandoning their desire to reduce world poverty and inequality and are instead using ODA for other purposes.

For example, in recent years, Australia has diverted ODA funding from hospitals, education, infrastructure etc and pumped it into maintaining the

privatised prisons on Manus Island and Nauru, where we have been sending people seeking refugee protection.

That is, for Australia, running prison camps is ODA!

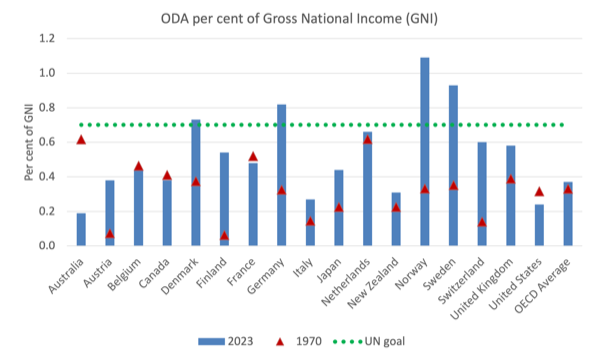

To see what the major Western economies have been up to, the following graphs are good summaries.

The next graph shows the movements in the ODA/GNI ratios between 1970 (red triangles) and 2023 (blue columns) for selected (advanced) OECD nations.

The dotted line represents the 0.7 per cent target.

In 1970, when Australia signed up to the 0.7 per cent target, we devoted 0.62 of GNI to ODA and we were a considerably poorer nation in material terms then now.

Most nations have failed dismally to honour the international agreement that they signed up for – to devote at least 0.7 per cent of GNI to ODA.

Two countries in this list – Australia and the US – have actually gone backwards since they signed in 1970.

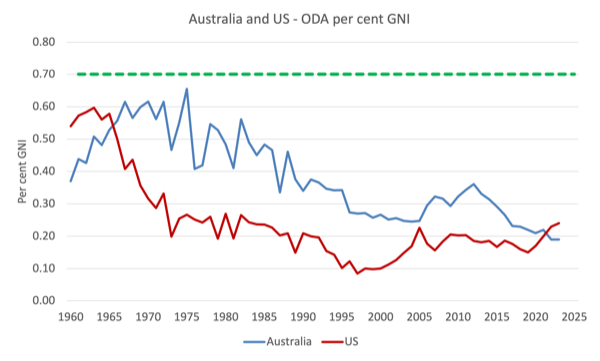

The following graph shows the time series from 1960 to 2023 of ODA/GNI ratio for Australia and the US (OECD data for this variable was first collected in 1960).

As neoliberalism and the fetish about fiscal deficits took over the public policy debate, these countries cut the proportion of GNI devoted to foreign aid.

For Australia, the ratio is now at record lows and successive governments have shown no inclination to reverse the downward trend.

Who knows what will happen with the USAid cutbacks.

The news reports are already indicating massive damage to the poorest people in the world is happening as a result of USAid initiatives being shut down.

The Chinese government has been fairly transparent with respect to foreign aid.

In 2018, it created the China International Development Cooperation Agency (CIDCA) and their – Belt and Road Initiative – has been a sound strategic intervention as they seek to increase their influence in the global economy.

In 2021, the Chinese government proposed the – Global Development Initiative (GDI) – to the General Assembly of the United Nations, which was designed to accelerate progress towards their 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (the so-called 2030 Agenda).

The AidData lab at William and Mary University publishes an excellent – AidData’s Global Chinese Development Finance Dataset, Version 3.0 – which helps us to understand what is happening with Chinese development finance.

Latest estimates suggest Chinese ODA/GNI was around 0.36 per cent and rising (so well above the US, for example).

While the Western nations have become increasingly infested with neoliberalism and have failed to honour international ODA goals, the Chinese have stepped into the void and used ODA to gain influence in various part of the world – the Pacific, Asia, Africa etc.

It doesn’t bode well then that Western nations are responding to the rising geopolitical insecurity with promises to increase military spending while at the same time cutting ODA.

Their ostensible justification is that they do not have the financial resources to maintain ODA in the face of an urgent need to increase military spending.

Guns versus Butter

This ‘justification’ harks back to the old ‘guns and butter’ stories that first-year macroeconomics students used to encounter early on in their undergraduate courses.

Students learn about ‘opportunity cost’ which just means that to evaluate the cost of using resource A in outcome A is the sacrifice of not being able to use the resource elsewhere.

As an aside, this is the principle that guides us in Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) to say that exports are a ‘cost’ – because a nation is sending its real resources overseas and depriving local users access.

Students also learn about the ‘production possibility frontier’ – which says that all resources are being used fully.

A nation that is operating on its PPF is at full capacity and cannot easily produce any extra output given its resource base.

The textbooks introduce students to the classic – Guns versus butter model – which says that if a nation wants to produce more guns (which is usually constructed as public spending) then it must forego butter production (usually constructed as private output) because resources have to be transferred from one allocation to another.

Accordingly, the opportunity cost of public production is the loss of private production.

Students rote-learn this nonsense and repeat it endlessly in examinations and essays before entering the labour market themselves whereupon they perpetuate it, usually dressed up as the statement ‘public spending is inefficient and private sector spending is market determined and therefore efficient’.

More generally, the ‘guns versus butter’ story tries to get students to understand the choices between defense resource usage and other possible uses.

Students then toy with evaluating the overall benefits of such choices which depend, in part, on the state of geopolitics.

But be clear – this story is about real (productive) resources not financial resources.

Moreover, most economies fail to fully utilise their productive resources.

And providing jobs for the unemployed when there are idle resources does not involve a trade-off – there is very little ‘opportunity cost’ involved, which is why governments should always maintain full employment and have a safety net – Job Guarantee – in place.

It should be obvious then that when characters like Starmer (I read that Trump was impressed by his ‘Sir’ title, which tells you everything really) tell the British people that they are facing a ‘guns versus butter’ type scenario and the urgency of the Russian threat means they have to increase military spending and cut ODA, they are not being frank.

Research from the Center for Global Development (published February 26, 2025) – Breaking Down Prime Minister Starmer’s Aid Cut – finds that:

… the UK’s Prime Minister Keir Starmer announced that he would fund an increase in the UK’s defence spending by cutting its aid budget from 0.5 percent of gross national income (GNI) now, to 0.3 percent in 2027 …

… he’s planning a reduction in aid to 0.3 percent of GNI which means a 40 percent cut, and the lowest share of GNI on aid going to overseas development since 1999. The only other time a Labour Government spent under 0.3 percent of GNI on aid since 1960 was in 1997-99 when Tony Blair took on Conservative spending plans when he first came to power.

The UK network for ‘organisations working in international development’ – Bond – has been tracking the implications of Starmer’s cuts – Prime Minister Keir Starmer announces cut to Official Development Assistance (ODA) to fund defence – what we know so far (February 25, 2025).

Even before the military announcement that came after pressure was applied by Trump during Starmer’s recent visit to the US, the UK was hacking into its ODA spending and international commitments.

And now, it has broken a major election promise:

In their manifesto ahead of last year’s election, Labour promised to “restor(e) development spending at the level of 0.7 per cent of gross national income as soon as fiscal circumstances allow.”

Of course, with the fiscal rules in place there would never be a ‘fiscal circumstance’ that would allow the UK to honour its commitments.

This is not a ‘guns versus butter’ choice, which is about real resources.

The British government is not facing a financial shortfall in sterling other than the self-imposed fiscal rules.

The fact that ODA expenditure does not really compete in terms of available real resources with military expenditure is also telling.

Moving towards the 0.7 per cent of GNI target for ODA is financially achievable even with an planned 0.2 per cent of GNI increase in military expenditure.

The fact is that the British government can achieve both goals.

I make no judgement on whether the extra military expenditure is necessary (I don’t know) although I suspect with so many bad actors in that region, including Russia and the US presumably bailing out of its historical military support for Europe, something has to change.

But I do know that the ODA helps improve the lives of ‘millions of marginalised people worldwide’ (Bond quote) and should never be cut.

I am aware of the debate about the effectiveness of ODA – whether it actually reaches the target rather than being eaten up by consultants and administrators.

But that is a separate discussion and cutting overall spending given the rise in poverty and inequality is not the solution to that issue.

Conclusion

This is another example of how mainstream obsession about financial constraints on currency-issuing governments leads to policy choices that devastate the most disadvantaged segments of humanity.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2025 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Perhaps America is overgoverned, and needs less States, rather than more. This may reduce the likelihood of knuckleheads getting elected into positions of power?

Resource constraints prevent additional spending. (Further exceeding Earth’s resource limits is inherently counterproductive to well-being. We’re toying with the generation of a significant non-linear ecosystem response.)

Your economic take always a good read Bill ! Your Geopolitical take not so much! Too influenced by the neocon neoliberal Globalist press!

Ian Mackie: Power ultimately rests with the State. It always has – whether it be a band or tribe (hunter-gatherer societies) of chiefdom or ‘State’ – and for good reason. It’s a matter of who ‘owns’ or who captures the power of the State. If State power didn’t matter, why would Trump have run for US Presidency three times, twice successfully? And why would morons like Musk be buzzing around him like flies to sh#t? The power of the State needs to be possessed by the masses (true democracy) and those elected to serve the masses need to use the power of the State to generate ecologically sustainable and equitable (oikonomic) outcomes – outcomes that benefit the masses, present and future. For all sorts of reasons, this doesn’t occur anywhere (State power is used by those who capture it to fashion an economic system resembling institutionalised chrematistics, a.k.a. neoliberalism), which is why true democracy is an illusion and not a single economy is based on oikonomic principles.

The USA is not over-governed. The USA has been poorly governed by the Left and the Right, probably since 1776. The ineptitude of the Left has led to the rise of the Right. The most vulnerable and disadvantaged Americans have had a gutful and are venting their anger and frustration out at the ballot box. The hubris of the incompetent Left prevents them from seeing or acknowledging this.

John: Resource constraints don’t limit the spending power of a currency-issuing central government (CICG). They limit what it and the rest of us can purchase and therefore how much we can all spend without triggering inflation. Bill’s point is that if the UK Govt spends more on defence, it won’t reduce its ability to spend (more) on ODA – a non-existent fiscal trade-off circulating amongst people who don’t understand the fiscal powers of a CICG, which is just about everyone, including the economics profession, who remain silent in large part because they, too, don’t understand the fiscal powers of a CICG.

If there are insufficient real resources (i.e., those for sale are already earmarked for purchase), the UK Govt can use its taxation powers to do what taxes are designed to do from a macroeconomic perspective – that is, reduce non-govt spending to provide the resource space for the UK Govt to spend more on everything, including defence and ODA. Since the UK population is amongst the 20% of the world’s population that consumes about 80% of the world’s resources, the extra spending on ODA would hardly constitute the robbing of UK citizens of something they have an equitable right to claim. Hence, the only debate should be whether the additional real resources that will be allocated to defence is a better use of the real resources than the forgone consumption and investment spending of a higher taxed non-govt sector (if there are no spare real resources at present), which is what Bill means when he talks about opportunity cost.

I can’t trust the USAID, they have done some good infrastructure projects like water desalination plants in Pakistan which could be shut down now with the cuts but they are very shady.

Like the time they started a social media site in Cuba to spread American propaganda

https://apnews.com/article/technology-cuba-united-states-government-904a9a6a1bcd46cebfc14bea2ee30fdf

Or the Ukraine Government privatization website for selling state assets, scroll down and you’ll see USAID logo (they haven’t bothered removing it).

I think the austerity, “sound finance” policies imposed by WB, IMF and foreign investors on the global south countries is the bigger issue than cuts in aid.

That’s an excellent synopsis, Philip, and I concur with much of what you write, especially your observation of US governance. It is the country whose ascendency parallels the Industrial Revolution and fossil fuel bonanza. Its currency is the reserve for oil – and all that flows from that resource. It knows nothing else. Everything it does is predicated on money and profit.

It’s naive to think the golden calf is somehow immune from exploitation, corruption and criminality – but that is exactly what has transpired.

As for peace, it can only happen when the warring parties lay down their arms. All of them. It is that simple and has always been so. But simple does not equate to easy. It takes real courage to acknowledge the obvious and work towards reconciliation, trust, collaboration and respect. Remind me why we need guns and bombs other than making profits for the MIC? Protection against animal predators – use tranquillising darts not bullets. Other than killing each other, weapons make no sense whatsoever.

It would take a very brave leader to say they were going to disarm and cease all weapons manufacture and sale; that their military would adopt a humanitarian role in principle. Imagine what could be achieved if the resources we squandered on killing each other and destroying much of the environment in the process, could be applied to the real existential threats facing humanity in this epoch.

But I don’t hear many voices on the world stage imploring we come to our senses. Just more of the same. Sure, we can fund anything we want as CICGs including money for more and ever more costly weapons. Just because we can do something doesn’t mean that we should. Perhaps it isn’t just the US that has become corrupted and infested by greed, avarice and malice.

Or am I just simple, stupid and naive?

Perhaps to illustrate how widespread this disease has become, I note tonight the comments of my own PM and Chancellor in the UK – extolling the virtues of increased military spending in Ukraine (and Israel & etc) for the oikonomy (thank you PL) in Britain. My local arms dealer BAE Systems’ share price increased 19% today on the news.

Just imagine, eh?