In the annals of ruses used to provoke fear in the voting public about government…

Field trip to the Philippines – Report

I have been working in Manila this week as part of a ‘knowledge sharing forum’ at the House of Representatives which was termed ‘Pathways to Progress Transforming the Philippine Economy’ that was run by the Congressional Policy and Budget Research Department, attached to the Congress (Government). I am also giving a presentation at De La Salle University on rogue monetary policy. It has been a very interesting week and I came in contact with several senior government officials and learned a lot about the way they think and do their daily jobs. I Hope the interactions (knowledge sharing) shifted their thinking a little and reorient to some extent the way they construct fiscal policy. This blog post reports (as far as I can given confidentiality) what went on at the Congress.

Ironically, I have been staying at a hotel that was built in 1976 to host the IMF/World Bank Annual Meeting in Manila.

It was the product of a massive government assistance to private property developers and construction companies.

Since then, the hotel has been the preferred choice when the top echelons of Chinese leadership including Xi Jinping, Hu Jintao and Jiang Zemin visit Manila.

Given that history I thought it was appropriate that I was housed there (-:

It is also adjacent to the central bank building (a huge complex) and the Department of Finance.

That also seemed appropriate (-:

And it is close to the waterfront promenade which is about the only place in the locality that one can go for long runs in the early morning without being killed by the manic traffic congestion in the Greater Manila area or die from exhaust poisoning.

But what might be a truly beautiful locality is somewhat neglected and rundown, which goes for much of the city and provides the government, in my view, with massive potential to create jobs to alleviate the chronic underemployment and poverty.

The Philippines is what world authorities call a middle-income nation.

In Manila, there are pockets of extreme wealth immediately adjacent to areas of crippling poverty where children lie in gutters absent from participation in education.

One runs past the highly protected Manila Yacht Club on the seafront where the marina seems to be housing some of the largest luxury boats one could ever see, and then immediately comes across countless people living in appalling conditions, who attempt to eke out survival selling all sorts of junk.

As an aside, in Melbourne, for example, I find younger people offer their seat on the trams to me in deference to my age, which still is a tradition in my home town.

The response to age in Manila appears to be hawkers coming up to me offering black market viagra for a few pesos (-:

Of course, I politely declined but wondered what visitors get up to in this city.

These hawkers are all over the place and one also regularly encounters very young children who come up and tug on your pockets seeking a few pesos.

It is almost Dickensian.

But it tells me there is tremendous scope for progress given the extent to which the nation is wasting its most valuable resources, a point I will return to.

The other thing that I have been musing about in relation to my current work on degrowth, delinking and breaking colonial dependencies is how far removed from such a narrative are nations such as the Philippines.

Everyone I have spoken to wants faster growth and material accumulation, which would be an outrageous aspiration in advanced nations but is perfectly understandable in the context of a nation like the Philippines.

Trying to bring those two ‘worlds’ together to save the planet is an almost insurmountable task and I will have further discussions today with officials to further understand this issue.

But walking through the streets of Manila – dodging traffic and motor cycles (and viagra sellers!) – the overwhelming feeling I have had is how far away from reaching a point where degrowth could become a topic of conversation in countries like this.

When I am living in Japan, it is easy to see such a narrative emerging.

But in Manila, it seems like a road to far.

That is a challenging thought.

On Wednesday (January 22, 2025), I travelled out to the House of Representatives complex near Quezon City, which is a 25 kms journey that can take two hours or so given the traffic congestion.

I was invited to come to the Philippines to speak at the workshop organised by the CPBRD of the House of Representatives.

My friend, Professor Jesus Felipe also spoke. He worked at the Asian Development Bank for many years and is now at De La Salle University in Manila.

In the past, we have worked together on ADB sponsored projects studying economic development in Central Asia and Pakistan and so we have a long working association.

The meeting was attended by more than 100 senior officials from the major economic policy areas of government – Central Bank (BSP), Department of Finance, Department of Treasury, Department of Budget Management, and other related policy making departments and economic research institutes.

These are the people who design and implement economic policy in the Philippines and so it was a really good chance to talk to those who influence things here in one room rather than having separate meetings which would have been impossible.

In his introduction, Jesus laid out the fundamentals of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) given that the Philippines has its own currency and floats it on international markets.

That introduction laid the foundations for my presentation, which began by noting that at the end of December 2024, the Secretary of Finance, Mr Recto (they call the responsible portfolio Minister Secretaries here in the way the US government categorises these positions) released the 2025 fiscal statement – Recto: PHP 6.326 trillion national budget for 2025 most powerful tool to deliver the biggest economic benefits to Filipinos, reaffirms DOF’s commitment to work hard in funding it.

The statement launched a 6.3 trillion peso national spending initiative which represented a 9.3 per cent growth in appropriations.

Government spending will constitute around 22 per cent of GDP in 2025, which the officials believe represents ‘big government’.

I pointed out that this was actually a fairly modest government footprint relative to other nations.

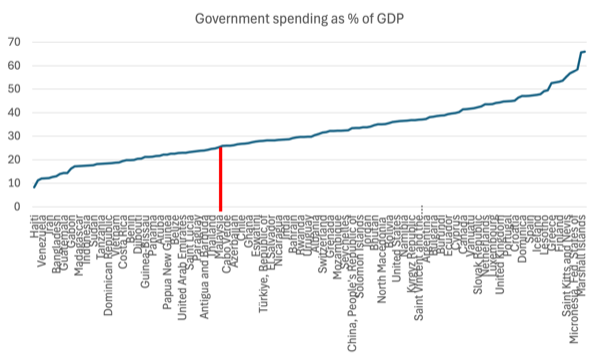

Consult the data – Government expenditure, percent of GDP – to see the point.

Out of 152 nations for which the IMF supplies this measure, the Philippines is standing at rank 53 (from smallest to largest) – so there are about 100 nations that have larger government sectors.

The following graph shows the distribution of the 152 nations and the vertical line demarcates the Philippines.

Surrounding the Philippines (in percentage of GDP) are

Qatar 24.3 per cent

Thailand 24.6 per cent

Cambodia 24.8 per cent

Malaysia 25.3 per cent

Philippines 25.9 per cent

Cabo Verde 26.0 per cent

Togo 26.0 per cent

Azerbaijan 26.2 per cent

Senegal 26.6 per cent

Chile 26.8 per cent

The Bahamas 26.9 per cent

The point is that perceptions are very significant influences on how policy makers think and in this case, the ‘belief’ that the government sector has a ‘large footprint’ when in fact it is relatively small, is an important ‘noise’ in the discussions.

The Secretary’s statement noted that of the 6.4 trillion national budget for 2025, 4.64 trillion was being supported by revenues, which is framing that conditioned my following discussion.

The statement also noted:

Secretary Recto reassured the public that the DOF will ensure that the country has enough funds to meet its needs and that every centavo will be spent efficiently on programs and projects that will greatly benefit the people.

And:

He emphasized that the DOF will strive to not just meet but exceed its revenue targets to generate more resources—just as the country’s strong fiscal performance this year has demonstrated.

In my slide I highlighted:

– “the country has enough funds”

= “to generate more resources”

– “strong fiscal performance”

And then posed the following questions:

1. What does “supported by revenues” mean?

2. What does “ensure the country has enough funds” mean?

3. What does “to generate more resources” mean?

4. What is a “strong fiscal performance” mean?

5. Most important question: Is this a full employment fiscal policy or not?

Those questions provided the talking points to further illustrate the essential differences to the way an MMT economist thinks and the mainstream framing.

The Philippines issues its own currency and has ‘infinity minus a peso’ spending capacity in financial terms.

So it makes no sense to spend a second considering that the government might not have enough funds (of its own currency) or by framing the fiscal challenge in terms of proportions of the total spending commitment that is ‘supported by revenue’.

Further, the focus on financial resources diverts attention from the real challenge – utilising the productive resources that are available effectively.

The day before the workshop I had taken a long walk (several kms) through the city and I saw a lot of ‘wasted resources’ – principally the citizens in the informal economy living in poverty with little work and shelter.

Generations of Filipinos in the streets and the children not in school and begging for pesos.

In the discussion yesterday, an official claimed that there was no fiscal space for the government because ‘everybody accepted’ that the nation was at full employment.

It was a stunning observation after what I saw the day before in the streets.

The official unemployment rate is low – true.

But even the official data shows that there are 15 per cent of the survey underemployed.

And 30 per cent of those classified as employees in the official data are classified as working in ‘Elementary Occupations’ – which are precarious, low-paid, and low-productivity activities.

But more stark is the fact that around 80 per cent of total ’employment’ is in the informal economy, not captured in the official data that is collected using the ILO’s Labour Force framework.

So to think that the nation is remotely close to operating at full employment is crazy and the problem is that that misperception or accepted version conditions the policy choices.

Which, in my view is why there is so much resource waste here and so much poverty.

For a few pesos, the government could make a massive difference to the lives of the poorest citizens.

In this context, I asked the following questions:

1. Why hasn’t the fiscal policy plan outlined a major public sector job creation program.

2. Why not provide jobs at least at a socially inclusive minimum wage?

3. Why not provide full-time positions to eliminate underemployment?

4. Why not provide training ladders within the jobs to increase skills?

The officials said there were some job creation schemes, but when one examines them it is clear they are small and do little to solve the national problem, even if they help the participants individually.

What they indicate is that scaling up these interventions would deliver massive benefits to the population and would provide a real chance to reduce the poverty and resource wastage.

The government’s aspirations are to create high-level manufacturing industries (become a leading producer of EVs, for example), but in my view they are a distance away from having the capacity to achieve that aim and would get much larger immediate returns by starting with job creation programs in the areas where abject poverty is the defining characteristic.

There urban areas need significant work to improve the quality of life – starting with cleaning the streets and the drains and the waterways.

When I go out running I see tens of thousands of jobs that could be relatively easily offered which would radicalise the local environment and improve the living standards here.

That would be a good place to start but the national fiscal statement did not allow for any such intervention.

I also discussed the proposition that the limited social security system here would soon ‘run out of funds’.

This is a repeating claim and is nonsensical.

The system, which is characterised by several different funds, has several problems, including low coverage and need to expand coverage and improve benefits.

But the schemes can never ‘run out of money’ unless the national government chooses that option for political purposes.

Spending precious time debating endless actuarial assessments that produce elaborate graphs showing insolvency points diverts the officials from the actual challenge.

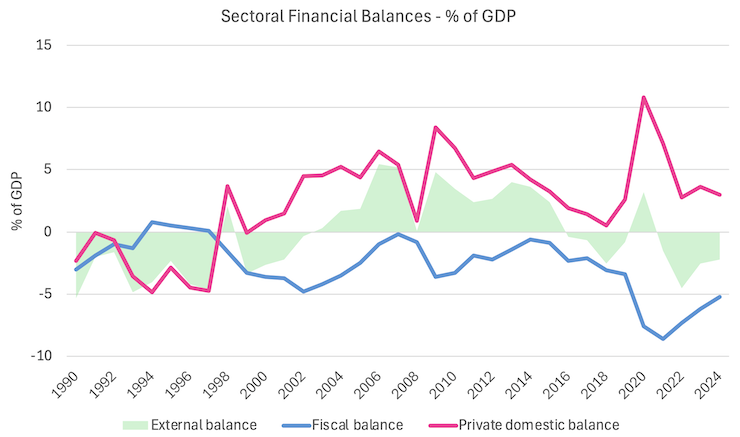

I used this graph which shows the financial balances of the government, external and private domestic sectors from 1990 to 2024 to illustrate some essential points.

It allows us to understand that when fiscal policy shifts, the private domestic sector’s financial balance shifts more or less in the opposite direction, if the external sector balance is relatively stable.

It also helps start a narrative about what happens when governments seek to reduce the fiscal deficit – which is the medium-term aim of the government.

Clearly, after the pandemic support, the government is now trying to reduce its fiscal position and that is forcing the private domestic sector towards deficit.

Such a growth strategy is ultimately unsustainable and there is evidence that private debt in the Philippines has grown substantially in the last several years.

Ultimately, the increasing precariousness of the private balance sheets will lead to a correction (spending reduction) and then the country heads to recession and the government is forced to increase its fiscal deficit.

I noted this allows us to differentiate between ‘good’ and ‘bad’ fiscal deficits.

A ‘good’ deficit results when the government fills the non-government spending gap to push the economy to full employment.

A ‘bad’ deficit is when the government tries to move towards surplus and the fiscal drag does not match the spending and saving desires of the non-government sector, and the resulting recession reduces tax revenue and forces the government to increase welfare outlays, which ultimately see the fiscal deficit increasing.

That led to a lot of discussion in the Q&A section of the workshop and prompted the ‘full employment’ comment I noted above.

The reality is that there is significant ‘fiscal space’ in terms of idle real resources in this country and denying that reality leads the policy makers down unproductive dead ends that spend time talking about financial ratio while ‘Rome burns’.

I also discussed the national debt issue and noted that during the early years of the pandemic the BSP basically credited bank accounts on behalf of the fiscal departments to fund the policy interventions.

For example, on March 23, 2020, the BSP purchased PHP300 billion BTr bonds and on March 26, 2020 it remitted PHP20 billion to the Treasury as dividends on the large holdings of government bonds held by the central bank (BSP).

This was a case of the government lending to itself.

Right pocket sells bonds to the left pocket and pays the left pocket interest returns, which are then remitted back to the right pocket of government as dividends.

It is an elaborate accounting charade that attempts to hide the reality that the government is just spending its own currency and does not need tax revenue or debt issuance to ‘raise funds’.

In that context, I asked the officials the following questions:

1. What does it mean for government debt to be ‘manageable’ (a term used by an official report when the rising public debt level was being scrutinised in recent years)?

2. What would happen if the government stopped issuing debt that is denominated in foreign currencies? (Around 35 per cent of total public debt is such and exposes the country to the vagaries of export markets – totally unnecessary).

3. What would happen if the Department of Finance simply stopped issuing long- and short-term domestic debt and instructed the BSP to see all government payments were cleared (think March 2020)?

4. What were the consequences of the government just lending to itself during the pandemic – good or bad?

5. What would happen if it simply wrote all of its government debt holdings off?

6. Who would notice?

Those questions prompted a lot of discussion.

Finally, at the end of the workshop, an official from the Congressional Policy and Budget Research Department (Mr Aquino) presented me with the following gift:

Which characterised the tremendous warmth and hospitality that everyone has given me during my stay here for which I am very appreciative.

Conclusion

Today I am off to the local university to present a seminar on why New Keynesian monetary policy prioritisation is a failed policy strategy.

Unlike yesterday, today will be a different type of talk, technical and academic.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2025 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Thank you, Prof. Mitchell, for your efforts in Japan, Philippines and around the world! Here is a letter just published in Hill Times (Canada), along with a footnote to the letters editor:

Re: Questions remain about how Liberals missed deficit target by over $20-billion, says PBO, Disregarding fiscal anchors has become ‘a unique feature’ of the current government, says Chrétien-era Finance Canada official Eugene Lang,

IAN CAMPBELL | January 9, 2025

Under the stringent watch of Paul Martin (1994-96), severe budget cuts decreased Canada’s economic growth by 3.5 percentage points, downloaded costs onto provinces, and led to an explosion of homelessness that still troubles us today.

The economy can be likened to a cup. While we want to avoid overfilling and causing inflation, neither should we underfill, tolerating unnecessary recession and an excess level of joblessness.

Today’s economic punditry ignore the high cost of keeping unemployed almost 1.5 million Canadians who are not contributing to economic production, and whose skill levels, mental health and family life deteriorate over time, leading to expensive and intractable social problems.

Real fiscal irresponsibility is failure to recognize that the job of government is not to meet arbitrary fiscal “anchors” but to create a fully productive economy that allows Canadians to earn income, contribute to society, and share the benefits.

Footnote:

1. William Mitchell is Professor in Economics and Director of the Centre of Full Employment and Equity (CofFEE), University of Newcastle, NSW, Australia

http://bilbo.economicoutlook.net/blog/?p=49936

“We cannot say anything about the goodness or badness of a fiscal position just by comparing financial ratios or numbers.

***

We need a functional context before we can make any assessments.

***

The context is provided by what the other sectors – private domestic and external – are doing and how well the government is meeting functional objectives such as full employment, high quality public services, etc.

The purpose of fiscal policy is not to record particular deficits or surpluses, but to use the capacity of the currency-issuing government to advance desirable socio-economic objectives.

If the government is achieving those objectives, then whatever the fiscal balance turns out to be will be the ‘appropriate’ balance.

***

Similarly, looking at levels of outstanding public debt and concluding higher is worse reflects a failure to comprehend what public debt is and how it arises.”

http://bilbo.economicoutlook.net/blog/?p=31487

“Forget the deficit. Forget the fiscal balance. Focus on what matters – employment, equity, environmental sustainability. And as we would soon see – the fiscal balance will just be whatever it is – a relatively uninteresting and irrelevant statistical artifact.”

Wonderful report. Great to hear you were well received. Please post your university talk if you can. Yes, degrowth is the duty of rich, privileged nations and classes first and foremost.

Very informative Bill. Paying attention to how the streets are when you travel is so important to getting a feel for the reality of life within a nation. If you only mingled with the PMC from hotel to venue to hotel you would have seen so much less than reported. For nations like the Philippines with such a large and scattered population and marked side-by-side wealth extremes it should be about ensuring self sufficiency in food production and energy as well as developing an adequate living environment for everyone before or while working up any grandiose manufactures, of such as EVs, for export to the benefit of foreigners.

Those in charge don’t want to do the social good stuff but want to be able to point to the “sexy” big ticket items for export as a measure of their political success and for public acclamation. A change of mindset isn’t easy. I hope that the reception of your explanatory words and answered questions will lead on to a substantive change but it’s a long hard road to hoe, as you well know. Persistence and more persistence. You will need a few local “product champions” to carry on the advance of an understanding of MMT into the Philippines. Best of luck in fostering such folks.

The debt trap means cutting government spending, until every penny the economy produces goes to pay interest on that debt.

The debt trap is the face of colonialism, both old and new.

Progressives are those who say “lets finish all remaining empires”; lets finish the debt trap.

Doesn’t look like it, right?

But then, there are so many thing we didn’t know about, right?

Somebody has been captured by the siren song of economic growth. 🙂

“In his introduction, [Prof. Jesus Felipe] laid out the fundamentals of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) given that the Philippines has its own currency and floats it on international markets.”

From what is stated later in the article, I would guess that what holds the Philippines back from “full” monetary sovereignty is the fact that the central government either issues debt denominated in foreign currencies (e.g., the US$) or is forced to borrow (from the IMF ?) in foreign currencies. Is this in fact the case?

I would like to know because in discussions of MMT we rarely hear from countries that have only some of the characteristics of monetary sovereignty.

So this is what neoliberal imperialism leads to….