I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Let’s just focus on inflation

It’s Friday and today has been very hot (nigh on 40 Celsius). One could also easily get hot (under the collar) just engaging in one’s daily reading given the amount of misinformation and sheer terrorist journalism and public commentary there is at present. The IMF released its latest Economic Outlook calling for a general return to surpluses. Why have we fallen prey to this insidious notion that government surpluses are normal and deficits are for fighting fires? In fact, the latter is more the truth. Surpluses are only required if the external sector is so strong that the economy will overheat if the government doesn’t drain private purchasing power. Anyway, I just stay calm through it all … like any good modern monetary theory (MMT) soldier. There is a war going on out there in ideas land and cool heads are needed.

The other day (November 15, 2009) I read that China has now become the biggest risk to the world economy and that:

Credit has exploded. Allocated by Maoist bosses for political purposes, it has become absurd. China is rolling as much steel as the next eight producers combined. It is churning more cement than the rest of the world. Fixed investment is up 53pc this year. Once you know that Hunan authorities have torn down two miles of modern flyway so that they can soak up stimulus by building it again, or that the newly-built city of Ordos is sitting empty in Inner Mongolia, you know what must come next.

I couldn’t help feeling that with a growing population they are going to need a few new cities – and buildings have to go up before people will live in them. So what’s the issue? That area of China (located in the Inner Mongolian Autonomous Region) is part of the Central Asian region that I am working on with the Asian Development Bank at the moment. My assessment is that it sure needs quality housing.

And while I do not support building roads and tearing them up again – if only from an environmental perspective – each time the Chinese government does that and employs the gang of workers to finish the project they sustain their national income and help workers support their families.

The point I would make is that the problem is a lack of imagination rather than something devilishly wrong with using fiscal policy.

Anyway, we are told that “you know what must come next”. I wonder what will come next from those evil Maoist bosses! Will they tear the city down before anyone moves there? They would be idiots if they did but that says nothing about the effectiveness of fiscal policy in creating jobs and underwriting private saving. It just says they are idiots.

Why didn’t this journalist find out how many jobs had been created directly and indirectly by the construction of the new city? That would have been a story to focus on rather than try to run the argument that they are a pack of evil communist wastrels.

And don’t all politicians whether they are evil and Maoist or Tory and whatever allocate funds for political purposes? (see below).

The article was one of many these days blaming China and its “beggar-thy-neighbour” policies for the continued “havoc with global trade” and risked “tipping the world into a second leg of the Great Recession”. Serious stuff.

Beggar-thy-neighbour policies refer to a stance that will benefit on nation but harm another. It arose in the convertible currency fixed exchange rate days (gold standard) when external surplus nations held all the cards. External deficit countries were forced under this system to contract their domestic economies so that they could hold their exchange rate at the agreed parity.

But in a flexible exchange rate system the concept doesn’t have much traction. In the case of China though, the commentators are demanding that it stop is peg against the US dollar. Why then are they also not calling for Germany to stop pegging its “economy” against that of Spain or Portugal. The former enjoys a strong trade position while the latter countries are bearing the brunt of the meltdown.

Apparently:

China is still exporting overcapacity to the rest of us on a grand scale, with deflationary consequences … By holding the yuan to 6.83 to the dollar to boost exports, Beijing is dumping its unemployment abroad – “stealing American jobs” …

Western capitalists are complicit, of course. They rent cheap workers and cheap plant in Guangdong, then lobby Capitol Hill to prevent Congress doing anything about it. This is labour arbitrage. At some point, American workers will rebel …

All the trading between the countries is voluntary. If the US workers do not want to buy the cheap Chinese goods then they have the capacity to boycott Walmart in their millions and start buying local crafts at village fairs instead.

It is astounding to me that the export-led growth strategy that China has followed has been eulogised by the mainstream economics profession as the exemplar of modern development and now China has proven to be good at it we don’t like it any more.

Ah, but it is all about that exchange peg. Then why does the US or any country allow any country to peg against anyone, including itself? Why does the mainstream advocate dollarisation in developing countries? Total hypocrisy is the only reason I can think of. When a nation is weak it suits the US to enslave it via dollarisation. But when it gets clever and gets the US population to buy stacks of goods that it makes, and, provides incentives (cheap labour) for the capitalists to set up shop there … then it is a different story.

The other point is that it reflects an obsession about trade that is at the core of mainstream thinking. The US Government has the capacity to spend US dollars to create any sort of domestic economy they would like. They are actually better placed than other places (such as Australia and most developing nations) because it still has a capital goods sector.

The Chinese are clearly attempting to expand their domestic market. As a poor country it didn’t have the health and aged support pension sophisticatation that advanced nations possess. A lack of this type of support leads to higher levels of household saving. The Chinese have already started to increase pensions and provide better health insurance for its citizens. Eventually local consumption will rise.

But this misses the point that as long as they are prepared to net ship goods and services in ridiculous quantities and as long as US citizens value those goods and services (why they do is a question worth exploring) – then both parties get what they want – the US a higher material standard of living and the Chinese some sense of security holding all those US denominated financial assets.

It is a perverted sense of values but the juxtaposition has been voluntarily arrived at. Further the current account deficit does not mean that the private domestic sector in the US has to be increasingly indebting itself as is the common misconception.

As long as the public sector runs a deficit as big as the current account deficit and the net saving desire of the domestic private sector then growth can continue without private leverage overall.

The article concludes with this:

The world economy is still skating on thin ice. The West is sated with debt, the East with plant. The crisis has been contained (or masked) by zero rates and a fiscal blast, trashing sovereign balance sheets. But the core problem remains. The Anglo-sphere and Club Med are tightening belts, yet Asia is not adding enough demand to compensate. It is adding supply.

So clearly it is up to the Anglo-sphere and Club Med to add demand. If China ends up with massive excess supply then that might be an environmental disaster (wasted resources) but cannot really undermine conditions in the advanced world.

If they try dumping even cheaper goods then the World has trade rules to stop that. The US could in those case also just impose exchange controls.

Anyway, this analysis resonates with the overnight call by US Democrat senator for the Congress to say no to the bill to increase the debt ceiling. This would effectively (under current law) put a cap on the deficit. Bayh said that a bipartisan push is needed to tame ballooning national debt.

You might like to read the blog response of my colleague Randy Wray to this call. I don’t intend to repeat what he has said.

Bayh reports that Congress are being asked to increase the “debt ceiling” that the US government imposes on itself. He writes that if they increase this limit there will be:

… dire consequences … Long-term deficits drive up interest rates for consumers, raise prices of goods and services, and weaken our country’s financial competitiveness and security.

The bigger our deficits, the fewer resources we have to make critical investments in energy, education, health care and tax relief for small businesses and middle-class families.

The bigger our deficits, the more we must borrow from foreign creditors like China, allowing governments with competing interests to influence our economic and trade policies in ways that run counter to our national interest.

So this is not a case of Maoist bosses running out of control in a fiscal frenzy but rather “respectable” democrats and GOPs who are also endangering the very fabric of the American economy.

The Latest IMF estimates are forecasting the US deficit will peak at 11.2 per cent of GDP this year, drop to 10.7 per cent of GDP in 2010 and 9.4 per cent of GDP in 2011.

To put that it perspective, in 1942 the US government deficit was 14.2 per cent of GDP, rising in 1944 to 30.3 per cent of GDP and then falling in 1945 to 21.5 per cent of GDP.

In the last 69 years, the US has only run 12 surpluses and each time it did a major downturn followed which pushed the budget quickly back into deficit.

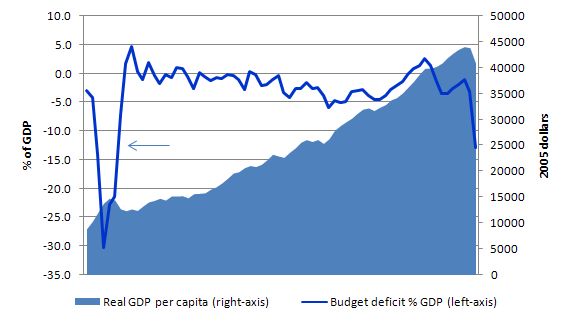

America enjoyed massive growth in its prosperity over the long period of deficits. The following graph shows US budget deficits as % of GDP and Real GDP per capita (in 2005 dollars) since 1940 (to 2008). The data comes from the US Bureau of Economic Analysis.

I put an arrow on the graph coinciding with fiscal contractions in the aftermath of the Second-World War. Have a look at the Clinton surpluses also. Both times GDP per capita declined (or growth slowed dramatically). If you look carefully you will see this pattern occurs regularly across the time period shown.

The contraction at the end of WW2 might be illustrative of what might happen if the deficit-terrorists got their way and Obama (himself being one) started cutting net spending. Real GDP per capita declined dramatically.

The other claims he makes with respect to interest rates are misleading in the extreme.

It is true that debt-issuance increases the term structure of interest rates which has distributional outcomes for borrowers and lenders. This follows directly from the fact that debt issuance allows the central bank to drain excess reserves and hold interest rates higher than they would otherwise be.

The link between the term structure and the real sector is not well established although it is usual to argue that the higher than otherwise rates damage investment spending. The evidence is weak. Thus, it is hard to consider the impact of debt-issuance to be a significant real sector cost, in the range of interest rate effects that are observed.

It is also true that the “bigger our deficits, the fewer resources we have to make critical investments in energy, education, health care” and that is because the whole purpose of net spending is to deploy resources that would otherwise be idle. So as long as the net public spending is targetting areas of public purpose and advancing welfare the fact they reduce idle resources is a good thing.

But the size of the deficits do not prevent the government from offering “tax relief for small businesses and middle-class families”. The decision to provide tax relief just comes down to whether the government thinks the private sector (or groups within it) should have a larger access to real resources than at present.

If it wants those groups to have more purchasing power then it can always give the tax relief without compromising its own net spending ambitions. There is no zero sum game operating here. The only question is whether overall aggregate demand is sufficient to drive output at levels which will achieve full employment.

If the tax relief is desirable and the increased purchasing power would drive nominal demand faster than the economy can absorb it then the government would have to cuts its own spending to provide “room” for the increased private spending.

This is not rocket science. But you have to understand what the purpose of net public spending is in the first place so that you don’t go down these illogical dead-ends that the Senator has trapped himself in.

Bayh then told us why he would be voting no in the bill to increase the capital limits:

… The easy path is simply to borrow until the credit markets will no longer allow it …

This approach violates something fundamental in the American character. Every generation before us has been willing to make the tough decisions and hard sacrifices required to ensure our children and grandchildren inherit a better way of life and stronger country. Now, it is our turn.

For this reason, I will vote “no” on raising the debt ceiling unless Congress adopts a credible process to balance our books and eliminate the red ink.

Well the even easier path is to stop borrowing altogether … and this is why in our little E-mail MMT Workshop today (a discussion of some sorts goes on most days between the MMT theory camp) the US contingent decided to advocate for a “NO” vote too. Surprised?

MMT tells you that there is no reason to borrow other than for operational reasons associated with draining bank reserves such that the central bank can “hit” a positive target interest rate. In the current crisis most central banks are now paying a competitive return on excess (overnight) reserves, which is equivalent to issuing debt anyway. Why?

It is equivalent because the payment of the overnight rate allows banks to earn on their idle reserves and stops them trying to off-load the funds onto the interbank market (meaning the central bank maintains control of its target rate). A bond issued is just a promise to provide a return on bank reserves – with the difference that the central bank drains the reserves out of the monetary system and gives the bond-holder a bit of paper. Upon maturity the reserves return … with the stroke of a keyboard … and the returns are paid as well. So functionally equivalent.

And I would refer you back to the graph above to wonder whether the grandchildren at various times would have hated their grandparents for allowing the government of the day to run a budget surplus.

The idea that it is necessary for the Federal government to stockpile financial resources to ensure the future generations are better off has no application. It is not only invalid to construct the problem as one being the subject of a financial constraint but even if such a stockpile was successfully stored away in a vault somewhere there would be still no guarantee that there would be available real resources in the future anyway.

Discussions about governments saving for the grandchildren completely misunderstand the options available to the Federal government in a fiat currency economy.

The best thing to do now is to maximise incomes in the economy by ensuring there is full employment. This requires a vastly different approach to fiscal and monetary policy than is currently being recommended by the deficit-terrorists.

If by chance there are sufficient real resources available in the future then their distribution between competing needs will become a political decision which economists have little to add.

Long-run economic growth that is also environmentally sustainable will be the single most important determinant of sustaining real goods and services for the population in the future.

Principal determinants of long-term growth include the quality and quantity of capital (which increases productivity and allows for higher incomes to be paid) that workers operate with. Strong investment underpins capital formation and depends on the amount of real GDP that is privately saved and ploughed back into infrastructure and capital equipment.

Public investment is very significant in establishing complementary infrastructure upon with private investment can deliver returns. A policy environment that stimulates high levels of real capital formation in both the public and private sectors will engender strong economic growth.

It is also ironic for the current mainstream belief expressed by Bayh and his cohort, that for all practical purposes there is no real investment that can be made today that will remain useful 50 years from now apart from education, in the hope that when the time comes we will best be able to deal with whatever real problems arise.

Unfortunately, they choose to address the problems of the distant future as monetary problems, and conclude that we need “austerity” today to prepare us for the future. And, both ironically, and as evidence of the lack of understanding of the real problems we could be addressing, public education is universally one of the first expenditures that are reduced.

Finally, a return to the pursuit of surpluses will ultimately be self-defeating. For all practical purposes any fiscal strategy ultimately results in a fiscal deficit as unsustainable private deficits unwind. But these deficits will be associated with a much weaker economy than would have been the case if appropriate levels of net government spending had have been maintained.

Financial stability as a public good

What would happen if the government didn’t issue any bonds? I will write more on this subsequently but here I just provide some sort of framework for thinking about this question.

As a political statement I consider the fundamental responsibility of government macroeconomic policy is to maximise real national output in a way that is sustainable (social, economic and environmental).

In a modern monetary economy this requires aggregate spending levels such that all those who wish to work have that opportunity. Further, the citizenry demands price stability as a matter of fairness and thus accept it as a legitimate political goal.

So the question is how debt-issuance will advance those goals.

The current financial system is linked to the real economy via its credit provision role. Both households and business firms benefit from stable access to credit. An economy’s financial system is stable if its key financial institutions and markets function “normally”.

To achieve financial stability:

- The key financial institutions must be stable and engender confidence that they can meet their contractual obligations without interruption or external assistance; and

- The key markets are stable and support transactions at prices that reflect fundamental forces. There should be no major short-term fluctuations when there have been no change in fundamentals.

A paper by A.D. Crockett (1997) ‘Why is Financial Stability a Goal of Public Policy’, in Maintaining Financial Stability in a Global Economy, a Symposium Sponsored by the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, Wyoming, August 28-30: 5-22, said (page 6):

Stability in financial institutions means the absence of stresses that have the potential to cause measurable economic loss beyond a strictly limited group of customers and counterparties. Occasional failures of smaller institutions and occasional substantial losses at larger institutions are part and parcel of the “normal” functioning of the financial system. Indeed, they serve a positive function by reminding market participants of their obligation to exercise discipline over the activities of the intermediaries with whom they do business.

Financial stability requires levels of price movement volatility that do not cause widespread economic damage. Prices can and should move to reflect changes in economic fundamentals. Financial instability arises when asset prices significantly depart from levels dictated by economic

fundamentals and damage the real sector.

Collapses brought on by injudicious speculation that do not affect the real sector or that can be insulated from the real sector by appropriate liquidity provisions are not problematic.

The essential requirements of a stable financial system are (taken from a Report written by Warren Mosler and me – Working Paper version):

- Clearly defined property rights;

- Central bank oversight of the payments system;

- Capital adequacy standards for financial institutions;

- Bank depositor protection;

- An institutional lender-of-last resort when private institutions refuse to lend to solvent borrowers in times of liquidity crisis;

- An institution to ameliorate coordination failure among private investors/creditors;

- The provision of exit strategies to insolvent institutions.

While some of these requirements can be provided by private institutions, all fall in the domain of government and its designated agents. However, we argue that none of these requirements rely on the existence of a viable public debt market.

Private goods are traded in markets where buyers and sellers exchange at prices that reflect the margin of their respective interests. At the agreed price, ownership of the good or service transfers from the seller to the buyer. A private good is “excludable” (others cannot enjoy the consumption of it without being party to the transaction) and “rival” (consuming the good or service specific to the transaction, denies other potential consumers its use).

Alternatively, a public good is non-excludable and non-rival in consumption. Private markets fail to provide socially optimal quantities of public goods because there is no private incentive to produce or to purchase them (the free rider problem). To ensure socially optimal provision, public goods must be produced or arranged by collective action or by government.

So it is clear that financial system stability meets the definition of a public good and is the legitimate responsibility of government.

But is achievement is not at all dependent on public debt-issuance.

What about the inflation bogey?

If the government continued to net spend but did not issue debt wouldn’t this just be printing money? Governments do not print money. Mints print currency notes for circulation. Governments do not spend by printing money. They rather credit bank accounts. Please read my blogs – Quantitative easing 101 and The deficit and debt debate – for more discussion on this point.

I heard a new theory the other day that sounded a akin to mainstream economics – well that association was made by someone who knows me the most and is eminently more literate than me. Phlogiston theory, was a wild-idea in the C17th that tried to explain oxidisation. Phlogiston … just say it out aloud a few times for yourself and enjoy the sound – was alledgely a “fire-like element … that was contained within combustible bodies, and released during combustion”. Mainstream monetary theory is similar in its alchemy – it posits strange unseen forces are afoot which cause chaos and are exclusively related to government spending.

Phlogiston theory started to stumble once scientists found metals that “gained weight when they burned” when the theory said that they would lose weight because they had lost phlogiston. All sorts of ad hoc responses were provided by the theorists to explain this. It took the founder of modern chemistry Lavoisier to show “that combustion requires a gas that has weight (oxygen)” that the theory was finally declared kooky.

Mainstream economics has been in denial about the effectiveness of fiscal policy for years preferring to promote monetary policy as the vehicle to stabilise the business cycle, which in modern times has become to scorch the real economy to keep inflation under control. Of-course, there is no evidence that inflation targetting delivers lower or more stable inflation rates anyway. Please read my blog – Inflation targeting spells bad fiscal policy – for more discussion on this point.

They teach students about the Neutrality of money which our favourite book (not!) Mankiw describes as (First edition Principles of Economics, p.616):

When the central bank doubles the money supply the price level doubles, the dollar wage doubles, and all other dollar values double. Real variables, such as production, employment, real wages, and real interest-rates, are unchanged. This irrelevance of monetary changes for real variables is called monetary neutrality.

[Mankiw then gives the following analogy to help students learn!]

… a similar change would occur if the government were to reduce the length of the yard from 36 to 18 inches: As a result of the new unit of measurement, all measured distances (nominal variables) would double, but actual distances (real variables) would reman the same. The dollar, like the yard, is merely a unit of measurement, so a change in its value should not have important real effects.

Now this is a good Saturday quiz (sort of an essay) question. Can you spot to devious sleight of hand here. It is not that he admits this might only hold in the long-run. This is based on his observation that if the government altered the length it would cause “confusion and various mistakes” – meaning that it could have “real” effects. Just like money supply changes – as he asserts. But this is not the devious part of the story.

The analogy breaks down because while the alteration of the unit of measurement is direct the increase in high powered money (via say net public spending) does not directly impact on prices. They just assume (assert) it does via the Quantity Theory of Money, which begins with an identity MV = PY, where M is the stock of money, V is the velocity or the times the stock turns over per measurement period, P is the price level and Y is the real output level.

Clearly from a transactional viewpoint this has to hold. All the transactions (left-hand side) have to equal the value of production (right-hand side). That doesn’t get us very far.

So the next thing they do is to assume that V is constant and ground in the habits of commerce – despite it moving all over the place regularly. They also assume that Y will always be at full employment so it can be taken as fixed.

Then like a child could conclude changes in M -> directly to changes in P (if V and Y are considered fixed).

So the assertion that the real side of the economy (output and employment) are completely separable from the nominal (money) side and that prices are driven by monetary growth and growth and employment is driven wholly by the supply side (technology and population growth), rests on the assertion that the economy is always at full employment.

Anyone with a brain could tell you that if business firms can respond to higher nominal spending (that is, higher $ demand) – either by increasing production or increasing prices or increasing both – and they cannot increase production any more (because the economy is at full employment) then they must increase prices to ration the demand.

That is a basic presumption of modern monetary theory (MMT). But typically, firms prefer to respond to demand growth in real terms to maintain their market share and thus invest in new capacity if they think spending will grow in the future and vice versa.

When the economy is in a state of low capacity utilisation with significant stocks of idle productive resources (of all types) then it is highly unlikely that the firm will respond to a positive demand impulse by putting up prices (above the level that they were before the downturn began). They might stop offering fire sale prices but that is not what we are talking about here.

Conclusion

All sovereign governments should stop issuing public debt forthwith. If there are legislative impediments preventing this then they should legislate those impediments away. Then we can concentrate on the real impacts of public spending and forget eliminate a lot of the nonsensical narrative that goes on about the evils of public debt.

Then the debate would focus on inflation … and the proof will be in the pudding! We will not be judging the net spending behaviour of the government on spurious grounds relating to misrepresentations of the impacts of public debt – that was created using the funds the government spent anyway.

That’s enough for today.

Admin note

There have been big storms around this way this afternoon and they have knocked my servers out a few times. If you were having trouble accessing the site that is the reason. Sorry.

Saturday Quiz returns tomorrow …

I have so many quotes this week that will make great questions … sometime tomorrow.

Dear Bill,

private good is “excludable” (others cannot enjoy the consumption of it without being party to the transaction) and “rival” (consuming the good or service specific to the transaction, denies other potential consumers its use).

Isn’t the “rival” condition sufficient? After all, if the good is consumed by the buyer then that surely excludes others. Or am I missing something?

Cheers

Graham