I have been a consistent critic of the way in which the British Labour Party,…

Civil society is in jeopardy in the UK as funding cuts erode local government capacity

I keep hearing from friends who live in Britain that I will be shocked when I get there on Thursday of this week after a nearly four year absence. One friend, who has just returned said that the deterioration in the public infrastructure is now fairly evident. Despite my absence, I have been keeping a regular eye on the data and so these anecdotal reports and reflections come as no surprise. It is obvious that the Tory government has sought a depoliticisation strategy by cutting local government spending capacity as a way of diverting blame for the consequences of their austerity push. The problem now is that after 13 or so years of Tory rule, the cuts are eating into the very essence of civil society in Britain. Like all these neoliberal motivated cuts, the cuts to council grants will prove to be myopic. The dystopia they are creating will come back to haunt the whole nation.

I wrote about this topic in these blog posts:

1. The austerity attack on British local government – Part 1 (April 30, 2019).

2. The austerity attack on British local government – Part 2 (May 2, 2019).

This document published by the House of Commons Library (September 23, 2023) – What happens if a council goes bankrupt? – provides some background on local government bankruptcy rules in the United Kingdom.

It was prompted by ‘Birmingham City Council’s issue of a section 114 notice on 5 September 2023’.

More recently, the Nottingham City Council filed a – Section 114 Report – on November 29, 2023.

The so-called – Section 114 notice – which are reports put out by the Chief Financial Officer of local government that ‘restricts all spending except for that which funds statutory services.’

While technically a local council cannot be declared bankrupt, the Section 114 Report has been interpreted as an ‘effective’ bankruptcy and prompts a new fiscal statement with extensive spending cuts.

The CFO for Nottingham noted when the Report was released it said that:

The council is not “bankrupt” or insolvent, and has sufficient financial resources to meet all of its current obligations, to continue to pay staff, suppliers and grant recipients in this year.

But:

… the council’s latest financial position … highlights that a significant gap remains in the authority’s budget, due to issues affecting councils across the country, including an increased demand for children’s and adults’ social care, rising homelessness presentations and the impact of inflation.

The problem for local councils in Britain can be traced back to the massive cuts in grants that they receive from the national government, which since 2010, have been obsessed with austerity and can depoliticise some of the damage by cutting local government income and then blaming the council for the subsequent cuts in services etc.

In Nottingham’s case, the council is Labour run so the blame can be shed onto the political opposition by the Tory national government.

What then follows are accusations from the national government that the local authorities are corrupt or financially incompetent in one way or another, which allows the real cause of the malaise to be hidden within the public debate.

A UK Guardian report late last year (December 6, 2023) – English town halls face unprecedented rise in bankruptcies, council leaders warn – said that around 20 per cent of the local governments in the UK would “fairly or very likely” have to file Section 114 Reports in the next year or so.

I last studied this situation when the Institute for Government released their report – Neighbourhood services under strain: How a decade of cuts and rising demand for social care affected local services – on April 29, 2022.

That Report noted that:

England’s most deprived areas were hit by the largest local authority spending cuts during a decade of austerity … The miles covered by bus routes fell 14% between 2009/10 and 2019/20, with deprived areas more likely to see reductions in routes … A third of England’s libraries closed in the same period, with more closures in the most deprived areas.

It noted the “the scope of the state has shrunk locally, across England” in the decade of Tory rule up to 2019/20.

Councils rationed their spending and scrapped a lot of discretionary projects which add value to their communities.

The problem was two-pronged.

First, the grants were severely cut thus compromising the supply capacity of local governments.

Second, the overall austerity inflicted on the nation as a whole caused a rise in demand for social care services, particularly in the most disadvantaged council areas, which then placed further pressure on the councils.

The Report noted that:

The combined effects of grant cuts and increases in demand for social care squeezed the rest of local authority spending, including neighbourhood services.

Some councils cut neighbourhood services by up to 69 per cent.

Given certain changes in the way the data is collected and classified it is a bit difficult to accurately assess the extent of the cuts to local government in Britain.

But the IFG Report concluded that:

… the UK government reduced grants to local authorities by £18.6bn (in 2019/20 prices) between 2009/10 and 2019/20, a 63% reduction in real terms.

That is a massive slug and the situation has worsened since as the cost-of-living pressures have increased following the early years of the pandemic.

Councils can respond by increasing the annual council taxes but as the House of Commons briefing (cited above) indicates – “Since 2012, the Government has set national limits on the amount council tax can be raised by annually” – which in the present situation means that there cannot be a ‘real’ increase in council tax revenue, given the national inflation rate, although there have been some exemptions where the financial situation is consider dire.

The most recent detailed time series data for annual local government expenditure was released by the Office of National Statistics on February 21, 2023 – https://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/governmentpublicsectorandtaxes/publicspending/datasets/esatable11annualexpenditurelocalgovernment.

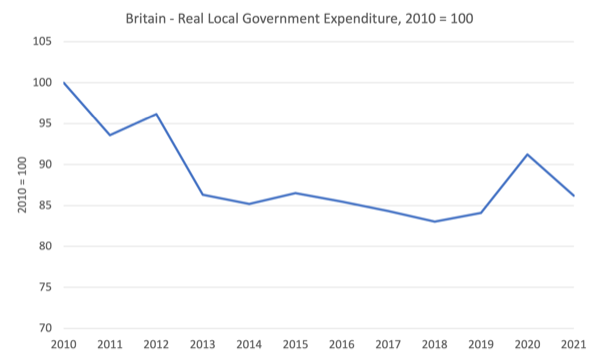

The following graph shows that between 2010 and 2021 (latest observations), real (CPI adjusted) total local government expenditure fell by 13.8 per cent.

When we get data for 2022 and 2023, the real cuts will be much worse than this and the demands on emergency, social care expenditures will have increased.

In effect, the Tories, among other sins, have ripped apart the very basis of civil society in Britain and the consequences will be long-lived.

The IFG reported – Local government funding in England (updated July 21, 2023) that total local government income (from “government grants, council tax and business rates”) was 10.2 per cent below 2009/10 levels by 2021/22.

They noted that:

The fall in spending power is largely because of reductions in central government grants. These grants were cut by 40% in real terms between 2009/10 and 2019/20 …

There is a major social-spatial dimension to this dilemma as well.

The poorer local government areas have lesss capacity to generate cash from council taxes and business rates than the more affluent places.

The demand for social care services is also higher in the most disadvantaged areas.

But the malaise is general.

I read a recent BBC report (January 9, 2024) – Hampshire waste tips and museums at risk as council cuts £132m – that some council authorities are going to turn their street lights off at midnight as well as other cuts to essential services.

There are two points I would make about this situation.

First, many of the cuts (museums, libraries, etc) are dismissed by people as being the domains of the woke who should pay for these services themselves.

I read an Op Ed this morning where calls for degrowth is dismissed as a woke demand that denies the reality of people in the so-called global south.

I will write about that in the future but I reject that criticism.

We do have to lift people out of material deprivation but that can be done without relying on past fossil fuel technologies.

It is not an either-or or zero sum game.

So, the Tories to some extent have been able to get away with these types of cuts because the buses still run, etc.

But what has been happening as a result of these stringent cuts by the national government is that local authorities have been diverting some longer-term spending into short-run emergency needs.

For example, diverting housing spending into crisis accommodation to help keep people off the streets.

So the story is a bit like this:

1. The central government squeezes total funds available to local authorities.

2. It increases or maintains their spending responsibilities.

3. Population grows and ages.

4. Overall austerity increases the number of people reliant on council service delivery.

5. Local authorities divert their shrinking funds into crisis areas.

6. They cannot cope.

7. They start drawing on their finite reserves.

8. Eventually, with public infrastructure in a degraded state due to lack of maintenance, people still in need, the local authorities are issued with so-called Section 114 notices – signifying they are “at risk of failing to balance its books in this financial year”.

9. At that point, the local authority is in breach of the law and the system of government becomes unsustainable.

But, it goes deeper than this.

I have argued before that these neoliberal-instigated changes represent a myopic strategy even if for the local governments they become essential given the crisis.

For example, see these blog posts, among others:

1. The mindless and myopic nature of neoliberalism (January 9, 2019).

2. More privatisation myopia (March 22, 2021).

3. We are undermining our futures by deliberately wasting our youth (March 2, 2021).

4. Mental illness and homelessness – fiscal myopia strikes again (January 5, 2016).

5. British floods demonstrate the myopia of fiscal austerity (January 4, 2016).

6. Public R&D austerity spending cuts undermine our grandchildren’s future (October 21, 2015).

7. The myopia of fiscal austerity (June 10, 2015).

Eventually, the strategy backfires and the outlays necessary to repair the damage outweighs the so-called ‘savings’ in the short-run.

The cited blog posts provide many examples of this myopia.

So, either civil society collapses or the national government has to eventually pay up to fix the damage done.

Then the payout is massive.

All the talk about the ability of privatisation and PPPs to risk shift (from public to private) is false.

The risk can never shift for an essential service – the state always has to pick up the tab when the private provider fails.

Second, the problem the Labour Party faces is now massive and their talk of fiscal prudence and rule-driven decision-making suggests to me that the crisis facing local governments will not be adequately addressed by them should they take power at the next general election.

I read a quote from Starmer while he was visiting Leicester recently – one of many cities in fear of the need to publish a Section 114 Report.

The Leicester Mercury article (January 9, 2024) – Keir Starmer says no quick cash for hard up Leicester if Labour wins general election – said that:

In Leicestershire alone, the city council has said filing an S114 is all but inevitable in the next 18 months, and the county council’s leader has said this year’s budget was the most challenging he had known.

And what did Starmer offer?

Nothing:

Local government funding has been a real problem. We’ve seen in a number of places, whether it’s Conservative-led or Labour-led, councils … [are] … struggling with finances. This is a result of the funding structure from the government, which is much too short term …

We’ll have to live within the constraints of an economy that’s been badly damaged in the last 14 years. So I’m not going to make promises I can’t keep.

So don’t hold your breath hoping that when Labour assume office the situation will change.

Fiscal rules that work against public purpose are part of the myopia I noted above.

Conclusion

Local governments are also going to be essential partners in the climate change response.

At present, the funding cuts are working against that need.

So not only is civil society being eroded, but the longer term responses are being undermined.

Human civilisation as we have known it over the last century – with all the ‘progress’ that has been made – is now becoming terminal.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2024 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

The ‘funding cuts’ for local government is a bit of a misnomer in the UK. The Localism Act permits local authorities to raise their council tax by as much as they want subject to a local referendum on the proposed budget.

Authorities are ‘bankrupting’ themselves because they don’t want to expose their spending proposals to scrutiny and a democratic vote.

I’ve had debates with people supposedly on the left who demand that they should have the right to raise funding as much as they want without reference to anybody. It once again demonstrates the left’s embrace of technocracy and this new way of thinking that the ‘betters’ should decide everything once they’ve captured institutions.

If councils put their budgets to the vote and they were rejected, which then resulted in a cut in services relative to other council areas, they’d have a stronger argument for national redistribution from Westminster.

As it stands it looks like an arrogant elite who have capture local institutions and they don’t want a light shining on their spending because of what it might reveal.

@Neil Wilson your faith in the democratic vote on a local government system rigged by a many years shift in funding reliance on central government grant, a grant system favouring wealthier regions (as Sunak happily boasted to the comfortably off in Tunbridge Wells), a progressively more unfair and unfit Council Tax system, which is just a limited modification of the Poll Tax, and taking account of a more stratified electorate, the poorest of whom don’t have too much unallocated income left over for a CT increase, is touching.

Don’t you think the time has come to bring people with government responsibilities, the IMF, the European Commission, the European Central Bank, etc. to justice for having consciously destroyed so much society and so many lives with austerity?

I really think that the people(s) have to revolt, the madness of austerity will not be stopped by the initiative of the austeritarians.

Greed above all things.

In the UK, in the EU, in the US.

If we already know that nothing will trickle down and that “free markets” are just a moniker for free monoplies, is it not kind of stupid to drink the same poison over and over again?

The council tax system is a modification of the previous rates system. It’s nothing like the poll tax, which was allocated to individuals.

It’s a property tax, and which occupiers suffers the burden is determined by the local council. Every council sets its own Council Tax Reduction scheme, which is usually reserved for the poorest people in society but doesn’t have to be.

The nub is that the property tax is a local tax that can be set at any level the council requires and they can rebate whoever they want to. That allows a clever council to alter the progressive nature of the tax if they want to. But they have to make their budget add up and put it in front of the people. Yet none have done so. Instead they whine about central government grants – much as the devolved parliaments do.

There is much a council is tasked with that is incompatible with a politically variable property tax and which needs elevating to a national institution: social care and road mending for starters. But we can’t even get to the start of a debate about those things until we get past the ‘somebody else should be paying for it’ attitude that remains prevalent in councils. Somebody else can’t pay for it. It’s about reallocating local resources for the public good.

We have to understand how property taxes work, and also how they don’t work if we’re to be able to put forward a rational MMT compliant proposal for taxation that is also politically realistic.

Is moving the expense and tax from the national (currency-issuing) level to the local (non-currency-issuing) level a way of undermining the power of the state by forcing the expense onto a non currency-issuer?

Here in America, movement of responsibilities from federal to state or local levels is a neoliberal move.

The movement of responsibilities to state or local levels puts pressure on services because American states cannot issue debt, and some localities (those most in need) find it hard to issue debt.

I would steal some words from Prof. Michael Hudson here: Taxes that can’t be paid,won’t be paid. Leicester could levy whatever taxes are approved, but if the money to pay the taxes isn’t there, Leicester won’t get the money. The town where I live is facing this problem. We have a considerable public debt, partly due to a notorious policy bungle by a state government, and we’re facing serious tax arrears, and if the municipality foreclosed and kicked the people out, they would live – where?

Related to something Hillary Clinton said a while ago: something like “All the high-GDP parts of the country supported us.” If you apply Clintonian parsing it makes sense. GDP in a region is a measure of consumer spending in that region. The people who are well-paid in the USA system tended to support Hils. The people who have been kicked to the curb by that system, not so much.

A government with a Central Bank has the authority to not kick people to the curb. If they abandon that authority, we see what we’re seeing.

@Neil Wilson

Although it is “characterful” and has a definite “sense of place”, the town I live in is one of the most deprived areas of England; and the financially-distressed local council is currently spending huge amounts of money on rip-off temporary housing, which is draining it of funds for almost everything else.

But the local population is poor, if not destitute in some (often very visible) cases, so the amount of funding that local council taxes, charges and fines could raise, without causing its inhabitants to financially struggle even more, is very limited. I’d be glad to be proven wrong, but would be very surprised if you could even get a majority of the residents to understand, yet alone turn out to vote for, a local referendum on how to raise and allocate the council budget.

There are the occasional (pitifully small, and usually one-off) external grants for certain limited and targeted improvements, but permanently increasing the central government grant to levels that existed before this municipal vandalism was undertaken would appear to be the only obvious route to any substantial improvement to the public sphere.

I totally agree with you that Care should be a central govt responsibility, and, in our case, the pothole epidemic is the responsibility of the Tory County Council – controlled by a different political party to the town council, which is now in some disarray, at least until May’s elections, following mass resignations from the Labour Party, and other issues.

I’m not sure whether the local gene pool could even furnish councillors, or officers, who are informed enough, capable, or even willing, to do the massive job required to improve our lot – not that there’s any better talent in central govt either.

It may be the case that some of the council’s decisions may have been poor or unhelpful in the past, though I don’t have any particular evidence or examples, but their hands have been effectively tied by ever decreasing govt support, exacerbated by ever-growing need, and there’s no obvious source of local wealth to replace it.

I have no idea of what a solution would look like, especially given our likely future national political trajectory to its destination of permanent austerity, and would fall into a deep despond about it all, except that there’s little point – once you finally abandon any hope of improvement, it becomes a lot easier to just observe and accept the decline.

@Neil Wilson you’re right that I erred in referring to CT as a limited modification of the Poll Tax. Indeed it more ressembles the rates system, in being collectable, which is pretty fundamental to a tax, and based on property (comparable to rental) value. Yet, in terms of the cost facing especially a 2 or 1 adult (discounted) person household, the capping of the maximum amount levied made the transition from Poll Tax to CT not a massive one for wealthier households (and a small rise in VAT penalised them even less) and increasingly a good deal given the vast differences in neighbourhood and regional house price movements in the last 30 years. Ah yes, councils have leeway over their reduction scheme, but they’d be even more cash-strapped if this was extensive. Then there’s business rates, yes more like rates except that central government takes half and decides how that will be distributed. So realistically not much room for progressive localism. Councils are not having a problem delivering services because of a ‘somebody else should be paying for it’ attitude but because they’ve faced massive increases in cost outside their control, yes for things like social services and met by central government controlling an increasing share of the purse while undermining local government in pretty much every sphere.

@Mel, you wrote, “Related to something Hillary Clinton said a while ago: something like “All the high-GDP parts of the country supported us.” ”

Ok, this is what happens when a party decides to only do things for the well of, and functionally abandons the bottom 66% of the nation.

Pres. Clinton did that in the 90s and Trump is the direct result. Biden is trying to undo that mistake, but his message is not yet getting through to the bottom 66%.

“Ah yes, councils have leeway over their reduction scheme, but they’d be even more cash-strapped if this was extensive. ”

That doesn’t necessarily have to be the case. Target Band H with a very high rate, which means setting a very high band D because that’s how the calculation works, then rebate people from G to A to make it more progressive.

It’s the net income that matters, not the gross numbers.

Where there’s a will there’s a way.

Patrick was right first time, council tax is a modification of the Poll Tax. It isn’t a property tax that would be recognised as such anywhere else – levied on occupiers, not owners – so are business rates. The old rating system was based on rental values and paid by owners. The Community Charge was payment for local services and so are council tax and business rates. A nice trick, because it’s landlords that benefit from local services in the rents they charge.

When Labour left power 50% of local authority funding came from central government, 25% from council tax, 25% from business rates, 50% now comes from council tax.

My local authority is one of many on the verge of bankruptcy. I don’t know whether they’ve even gone down the speculative adventure avenue, which many others have been tempted to do in their desperation to ‘make some extra dosh’. These are the ones in most trouble.

Interestingly a report by the Northern Powerhouse Partnership, chaired by George Osborne, proposes to devolve responsibility for their own funding to local authorities using land value tax and abolishing all other ‘property taxes’. This was mentioned in an FT article last year with Osborne quoted as supporting LVT. It’s a shame they’re not going to win, but…

Although LVT could no doubt produce all the revenue required, as proposed the system would still be grossly unfair. Just like with council tax the wealthiest authorities would set the lowest rate – the owner of a mansion in Mayfair pays little more council tax than the tenant of a bedsit in Portland which is one of the most distressed towns in England.

A few years ago I co-authored a paper on how to introduce LVT where we proposed different a high rate for income-generating land (or potentially income-generating, like second homes) and an ‘affordable’ rate for primary homes, i.e. rates calculated to be revenue neutral for each local authority. MMT shows there’s no need to worry about revenue neutrality, but ‘affordable’ is important – it could be set very low and increased as taxes on earned incomes are gradually abolished (so much could be achieved!). LVT should be collected by central government and funds allocated primarily on a simple per capita basis.

I served on a county council for a while, in the US, but I have a hard time imagining that this particular issue is so different across the pond. In my experience, local government is not led by the elected officials, but by the bureaucracy, and that’s doubly true with budgeting. When budget season came along, we got hundreds of pages, and I don’t think I’ve read, before or since, a book that was so long and theoretically so technical and said so little. Knowing the projected total gross salary for a governmental department tells you very little about how that money will actually be used.

I probably should’ve dug deeper on a whole lot of things, but man, I have a life, and you’ve gotta pick your battles. Worse, no matter what scrutiny I might’ve done, it wouldn’t have mattered, since a majority of the council liked the bureaucracy’s boots. Even the occasional moral victory against the bureaucracy ultimately didn’t matter, since running the government for themselves is a 9-5 for hundreds of people, while trying to oversee them was something I tried to do on the side—of running a small business.

Point being, as a councilor I was far more engaged than the average citizen, and I could only pierce the bureaucratic veil once in a blue moon. What exactly is supposed to happen if a budget is proposed to the whole electorate?

Hi Bill,

Thanks for coming to Britain. Will you be talking about the special role of our currency issuing government to local councillors anywhere, including Green Party ones – an increasing band?

And the organisations of the Left too – the unions and pressure groups who all seem to think that “Tax the rich” will provide the money needed.

I’m all for curbing the power of the wealthy class, and taxing must be one way forward on that. But we on the Left need to understand that we can do it with state issued money – taxing the rich isn’t the vital first step.

Neil Wilson

January 22, 2024 at 19:34

As much as this may be true, individual councils are scared to death of using council tax to raise funds. The Government have created an environment of fear. And as seen since the initial Osbourne budgets from 2010 councils are not very good at work collaboratively across the country as there are still political divides. It’s very sad but something needs to happen very, very soon as the conservatives have driven the country to the wall.

@Neil Wilson

You can read a 2023 Parliamentary report explaining “excessive” Council Tax rise referendums, and while what you argue is technically correct, the reality is somewhat different. Only one Council, Bedfordshire has tried a referendum and it lost. That cost the council £600,000. Surrey proposed one, but withdrew it. In the report it makes clear that the purpose of the referendum is to act as a veto – it’s a transfer of the capping power of the State to local residents.

Whether a rise is excessive is set by the Secretary of state and it is based upon the rise set for Band D. Your idea for increasing Council Tax and then offering rebates would very likely trigger a referendum, which the council is very likely to lose – try explaining to people that their council tax is going up, but they might get a rebate, on a referendum which has to include the word “excessive” on it.

I think your assertion that councils don’t want a light shining on their spending because of what it might reveal, I don’t believe is an accurate summary. I would suggest it is much more likely to be that they will spend £300,000+ on referendum which will get a no vote anyway – which is the purpose of the legislation. To devolve responsibility from the Government, so that it can pass on the blame. And as other posters have explained in many areas, there is little realistic prospect of collecting the rise, even if they were successful – there are £4.9 billion in council tax areas (2022).