In the annals of ruses used to provoke fear in the voting public about government…

RBA monetary policy decision represents a terminally broken policy model in Australia

Yesterday (November 7, 2023), the Reserve Bank of Australia raised its policy rate target for the 12th time since May 2022 by 0.25 points to 4.35 per cent. It was an unnecessary increase, just like the eleven increases that preceded it. And, from my perspective it represents a broken policy model. The RBA policies are transferring income and wealth from poor to rich at rates not seen before in this country. They are pretending that the inflationary episode is demand-driven (excessive spending) whereas the data shows that it remains a supply-side phenomenon and the major drivers will not fall as a result of interest rate increases. In fact, one of the major drivers – rents – are rising because of the interest rate rises – RBA is thus causing inflation. The RBA is systematically wiping out wealth at the bottom end and transferring to the top end. The cheer squad for these rate hikes are the wealthy shareholders of the major banks who are recording record profits. A broken model indeed.

Record bank profits and RBA monetary policy decisions

Earlier this week (November 6, 2023), we learned that one of the big four retail banks in Australia, Westpac recorded a 26 per cent increase in their annual net profits, a sum of $A7.2 billion, which means its shareholders will be banking extra dividends this year.

The bank’s management indicated they would be using $A1.5 billion as a ‘share buyback’ which just means it buys some of the existing shares back, reducing the overall shareholding and spreading the profits over a smaller shareholding – which further rewards investors and pushes up the bank’s share price.

The result: a big boost to those with wealth invested in the bank.

Overall, the banking sector in Australia has increased its margins – the rate it loans out money relative to the rate it pays depositors – and it has been able to do that beause the Reserve Bank of Australia has pushed up interest rates.

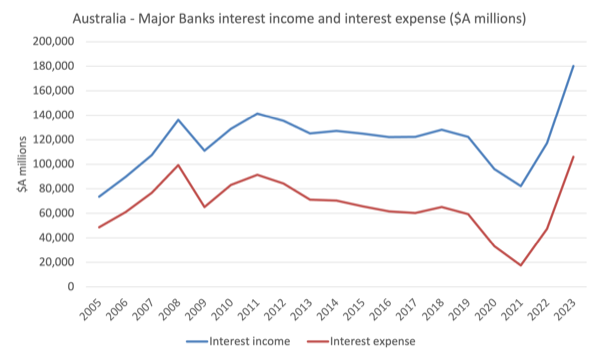

The first graph shows annual data from the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) for the interest income and the interest expense ($A millions) for the major banks in Australia up to March 2023.

The 2023 result is just 4 times the March-quarter outcome.

The ratio of income to expense has widened considerably since the RBA started hiking rates in early 2022.

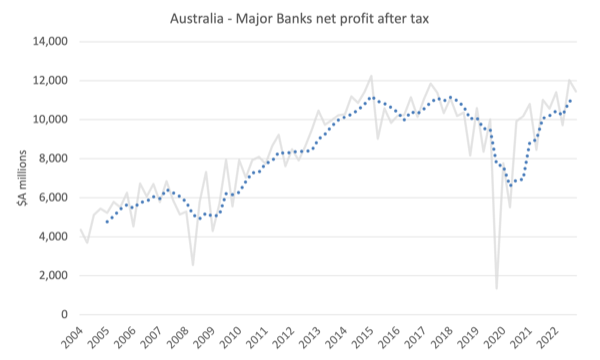

The next graph shows the net outcome – Net profits after tax for the major banks – using the underlying quarterly data.

The dotted line is a 5-quarter moving average to smooth out the fluctuations in the quarterly data.

It is easy to see why the major banks are now living it up.

Yesterday (November 7, 2023), the RBA hiked interest rates again while residents of Melbourne enjoyed a public holiday to celebrate a horse race of all things.

The policy target rate is now at 4.35 per cent, which is the highest it has been since 2012.

This added around $A100 per month to the average mortgage of $A600,000, and. since May 2022, the average mortgage holder has seen their monthly payments rise by around $A1,560, a massive impost by any measure or 52 per cent.

The RBA has now hiked rates 12 times since May 2022 and the shift from 0.25 per cent in April 2022 and its current level is the fastest escalation we have seen for many years.

The following graph shows the history of the RBA’s policy rate decisions since 1990.

Within this history are a series of mistakes, overreactions, and reversals, which go to the heart of the broken policy structure within Australia and globally, where the ‘central bank independence’ myth has been allowed to run amok.

The two outcomes – massive boost to bank profits and RBA rate hikes – are directly connected.

The latter provides the capacity for the banks to achieve the former.

And as more Australian mortgage holders segue from fixed rate contracts to variable rates in the next several months, the private banks will see their profits increase even more.

Have you ever wondered why commentators from the commercial banks, who are overwhelmingly featured in finance reports on the ABC and other media outlets, typically urge the RBA to push up rates to prevent the economy from ‘overheating’?

These commentators are held out to the public as independent industry experts, when in fact they are just boosters for their companies.

They know full well that constantly telling the public that rates must rise to ‘fight’ inflation is just a smokescreen for their special pleading to boost their companies’ profits.

The RBA’s own research – The Impact of Interest Rates on Bank Profitability: A Retrospective Assessment Using New Cross-country Bank-level Data (published June 2023) – demonstrates that when they push up the target policy interest rate, bank profits head towards the stratosphere.

The situation is even more loaded when we realise that while the winners of the RBA policy are the wealthy segments of our society, the losers are usually at the opposite end of the income and wealth spectrum.

The RBA promised borrowers that if they took out large mortgage loans in 2020 and 2021, they could assume that rates would not rise until 2024.

Of course, it was stupid of the then RBA governor to make that statement.

But the rate rises since 2022 have significantly punished an increasing number of borrowers, and the pain is concentrated on the lower income groups in our society who have very little ‘income’ leeway to absorb the substantial increases in mortgage payments.

It is not too simplistic to see this as a massive income redistribution from the poor to the rich, engineered by the central bank.

The RBA claims the rate hikes are not hurting households all that much because they have prior savings to draw upon.

Think about that.

Low income families have virtually zero saving buffers.

Of the better off families that do have some savings to draw on, the latest national accounts data shows they are running down those stocks quickly.

So what wealth the lower ends of the distribution might have had is being quickly destroyed by the RBA policies and redistributed to those with immense wealth.

The RBA decision and why it represents a broken system

The words used by the RBA in its – Statement by Michele Bullock, Governor: Monetary Policy Decision – is interesting.

First, the RBA said:

Inflation in Australia has passed its peak but is still too high and is proving more persistent than expected a few months ago.

So, the RBA once again proved how poor their forecasting performance is.

It seems that they now want to double down because they were wrong in previous analysis.

While I think that just means that their underlying analytical New Keynesian framework is not fit for purpose, the RBA doesn’t do introspection and just go harder in the (wrong) direction.

A broken model.

Second, the RBA said that:

While the central forecast is for CPI inflation to continue to decline, progress looks to be slower than earlier expected. CPI inflation is now expected to be around 3½ per cent by the end of 2024 and at the top of the target range of 2 to 3 per cent by the end of 2025. The Board judged an increase in interest rates was warranted today to be more assured that inflation would return to target in a reasonable timeframe.

So, the RBA thinks it has to undermine the economy because the falling CPI inflation is not falling fast enough.

What does ‘falling fast enough’ actually relate to?

Well, there target range of 2 to 3 per cent?

Why is that the benchmark upon which monetary policy decisions are based?

Remember that the 3 per cent Stability and Growth Pact deficit rule in the Eurozone was arbitrarily pulled out of the air by French finance officials one night late in Paris to satisfy political aspirations of the then President and has no correspondence with any economic theory, yet now carries the weight of an immovable benchmark – as if it is scientific in some way.

In the same way, the 2-3 per cent range that RBA inflation targetting claims is the desirable range was similarly arbitrary and came from the Reserve Bank of New Zealand, when it was flexing its ultra-neoliberal muscles in the early 1990s (as the first central bank to announce it was going to adopt a formal inflation targetting approach to monetary policy).

The RBA says it must get the inflation rate down to 2-3 per cent as quickly as possible, even though that target rate has no basis in any legitimate economic theory.

In other words, it is just a self-imposed rule without any justification.

Why is this range better than a 1 per cent inflation target, or a 4 per cent, or a 10 per cent?

There is no science at all to guide that.

The thing that matters for economic decision making is that inflation is stable.

A monetary system can adjust to any level of inflation as long as the inflation rate is stable.

So claiming they have to accelerate the pace of the contraction has no basis in economics at all.

Further, they use a NAIRU (non-accelerating-inflation-rate-of-unemployment) in their decision making but that estimate, inaccurate as it is, has no correspondence with the 2-3 per cent rate.

On that, recall as late as June this year, the new RBA governor was claiming the NAIRU was 4.5 per cent and they had to tighten monetary policy (push up interest rates) to force the unemployment rate up to that level to stabilise inflation.

It is hocus pocus of course.

Because with the unemployment rate at the time around 3.5 per cent and it had been steady at that rate for some time, inflation was falling relatively quickly, which meant the NAIRU had to be below the 3.5 rate.

The theory is that if the unemployment rate is above the NAIRU, inflation decelerates and vice versa.

In yesterday’s statement, the RBA noted:

Given that the economy is forecast to grow below trend, employment is expected to grow slower than the labour force and the unemployment rate is expected to rise gradually to around 4¼ per cent. This is a more moderate increase than previously forecast.

So now, just a few months after the 4.5 per cent estimate, the RBA is claiming the NAIRU is 4.25 per cent.

They have based 11 interest rate rises on the 4.5 per cent, which means they were tightening too much, if the NAIRU is now 4.25 per cent.

The point is not to follow this logic closely – it is nonsensical.

The point is that the RBA has no idea what is going on – they keep admitting things have shifted above or below their forecasts and so on.

This is a broken system.

Finally, the latest CPI data revealed a declining inflation rate with some persistence.

But like a Pavlovian dog, the RBA was motivated to push up rates again.

The issue of whether the 2-3 per cent targetting range has any basis aside, the factors driving the inflation rate at present are not related to excessive spending by households.

Rate hikes only discipline inflation if the sources of the inflation are sensitive to interest rate changes.

At present, CPI inflation is being driven by escalating rents, which in part is due to landlords passing on past RBA rate hikes to tenants.

A case of RBA interest rates causing rather than suppressing inflation.

The other major drivers are OPEC oil price rises being passed into petrol prices and the profit gouging by the privatised electricity companies.

Neither of which are going to be sensitive to the RBA decisions and will resolve over time anyway.

There was no case for the RBA to increase rates but in doing so it has further increased wealth inequality in this country and further entrenched the power of the elites.

This is one example of our broken system.

In Japan, where I am currently working for a while, the Bank of Japan has kept rates unchanged throughout this inflationary episode because it formed the view, correctly, that the inflationary pressures were coming from the supply side and interest rate changes would do little to fix the problem.

They realised those supply-side pressures would abate as the world adjusted to the disruptions caused by the pandemic and that they would just wait the inflation out without causing families with mortgages more pain on top of the cost-of-living pressures.

Conclusion

There is another way, but our blind policy makers refuse to see it.

And sitting pretty are the bank shareholders who count the extra profits with glee with little regard for the low income families who are now enduring massive burdens.

Who ever said that the RBA was independent.

They are in fact agents for capital and have deliberately pursued policies that increase inequality and punish the least well-off members of our society.

It is a broken system.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2023 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

The first known “inflation target” was set in NZ in 1990. Then Finance Minister Roger Douglas (“Rogernomics”) wanted the new Labour government to appear “tough on inflation”, so put a target of 0-2% into the Policy Targets Agreement with the RBNZ. It was and remains nothing more than a number that Roger pulled out of his arse. (source: Reddell, M. (1999). Origins and early development of the inflation target—Reserve Bank of New Zealand—Te Pūtea Matua. Reserve Bank Bulletin, 62(3). https://www.rbnz.govt.nz/hub/publications/bulletin/1999/rbb1999-62-03-06)

Globally, inflation fell towards 2% anyway by about 1994, so all the other reserve banks thought that would be a nice target since they wouldn’t have to do anything to achieve it at that time. That’s when the RBA settled on 2-3%.

The whole thing is a crock of shit. Roger later left Labour, to form the extreme neoliberal ACT NZ party.

How much does it cost to buy a seat on the RBA board ?

We have a saying that goes like this: “gorge on villainy”.

It was the call for buccaneers to loot.

Of course, there were also those who worked for the king, the corsairs.

Corsair or buccaneer, they have something in common: they´re both thiefs.

Royal or common, the same abhorrence.

If there is inflation? wouldn’t it be better to increase taxes. At least these could be targeted.

Oil—with its high energy density—is proving impossible to replace at reasonable cost (e.g., Ørsted wrote off $4B+ in wind power investment last week).

With the realization that *there is no green replacement for oil* (electrification is not green), metals prices have collapsed (lithium, cobalt, nickel), sending the Aussie dollar to new lows (Australia’s broken commodity export model at work).

The RBA moved to defend the AUD, but raising rates will trigger yet more reduction of Australia’s commodity exports (higher prices versus other commodity exporting countries).

Would increasing the Bank’s Tier 1 capital requirements be an alternative way to reduce the money supply/fight inflation, instead of increasing interest rates?

“Independent” (itself a canard) central banks are, by design, aristocratic institutions inimical to labour.

Its great to have an alternative economic viewpoint to provide balance to the prevailing orthodoxy and I really find Bills blog useful reading.

The comments, however, rarely challenge the propositions put forward.

The idea that interest rates are a bonanza for the banks is incorrect at least at the present time.

Lets take the example that Bill used – Westpac.

The share price was 23.87 in May 22 and fell again after the last interest rate rise to 20.86.

Over that time 2 dividends have been paid for a total 1.42.

A total return for the owners of about -6%.

Yes there are margin increases, profits may have increased in the short term but the total return is falling because of the expected effects of interest rates rises on bank profitability from increased provisions and reduced volume of lending.

Banks are notoriously leveraged to the economy.

In the period from 2013 to 2019 when intesteest rates where low and falling westpac paid annual dividends of $1.90 in excess of current dividends.

This is not a defence of banks and their role – just pointing out that the owners – what ever you think of them – and they fairly widespread in australia – virtually everyone on a salary – are not enjoying a windfall. I havent looked at the other 3 big banks but a quick look at market cap suggest a small fall over this period as well. There is usually not much difference among them.

update – missed one dividend payment!

so dividend return for the 18 months is $1.95 and total return slightly better but still negative or even depending on where you draw the line

Dear Jim (at 2023/11/12 at 10:40 am)

Thanks for your contrary comment.

However, as a sector, the major banks have not gone backwards over the course of the RBA interest rate hiking cycle. It is true that if there is a major recession then their profits growth will stall but so far that has not occurred.

Also it is difficult to come up with comparative data – where we have meaningful starting points before or just after the rate hike cycle began in early May 2022 because the four major banks were being impacted by other factors such as their differential exposure to the revelations of the Royal Commission.

The following data is defensible just as others could defend different share price starting points.

Further the comparison excludes the generous dividend payments that have been made and the various and significant share buy-backs (on- and off-market) that the four major banks have been variously engaged in, which have further enriched the shareholdings.

I also haven’t mentioned the massive boost that the banks are getting courtesy of the extra interest payments the RBA is paying the major banks on their excess reserve holdings.

The banks do not even have to do anything to reap that bonus – worth billions.

Ignoring those items, when I look at the data below, I cannot make a case that the four major banks have been adversely impacted by the RBA rate hikes.

ANZ

Market Capitalisation:

FY 2022 $68.1 billion

November 10, 2023 $76.54

Share price:

March 8, 2022 $24.625

November 10, 2023 $25.47

Commonwealth Bank

Market Capitalisation:

FY 2022 $153.6 billion

November 10, 2023 $169.76 billion

Share price:

March 2, 2022 $94.70

November 8, 2023 $100.69

National Australia Bank

Market Capitalisation:

FY 2022 $90.8 billion

November 10, 2023 $89.05 billion

Share price:

June 14, 2022 26.84

November 10, 2023 28.46

Westpac

Market Capitalisation:

FY 2022 $72.3 billion

November 10, 2023 $73.20 billion

Share price:

June 14, 2022 26.84

November 10, 2023 28.46

best wishes

bill

Thanks Bill for looking at this.

Its always difficult looking at 2 data points to make a case.

Prompted by your reply I did what I should have done which is look at MVB:ASX – an index EFT of the Australian Bank – to my eyes looks like a small decline in value over the last 18 months (but probably slightly positive taking into account 6% annual yield). When you look at this data from inception in 2014, there is a small gradual increase in valuation (again not taking into account interest rates). If you plotted this against interest rates I doubt there would there would any correlation. I guess the general point I am making is that interest rates, in themselves, seem to have minimal impact on bank profitablity – at least in Australia – where their priveledged position means they are or less profitable across the cycle.