In the annals of ruses used to provoke fear in the voting public about government…

Kyoto Report 2023 – 1

This Tuesday report will provide some insights into life for a westerner (me) who is working for several months at Kyoto University in Japan.

Well I am back in Kyoto for several months and it is hot and humid – unseasonally so really.

And bushfires are already causing havoc in Australia just as Winter has ended, when they bushfire season is historically only starting later in Summer after some hot, dry months.

Worrying.

Tameguchi and Keigo, not to mention Teineigo

I discovered today that there are phases one goes through when learning Japanese in terms of the way the locals respond to you in conversation.

The Japanese language is quite complex in ways that English is not.

While the grammar is much more straightforward than English, complexity lies in things like learning the difference between polite or honorific Japanese – 敬語 (Keigo) and casual Japanese and casual – (タメ口 or Tameguchi Japanesemodes, within which there are shades that one has to ultimately learn.

When using tameguchi, one is assuming that everyone in the conversation is equal, peer to peer, whereas honorific Japanese establishes through the language a differentiation or distance between the people having the conversation.

That distance might be between ‘young’ and ‘old’; ‘boss’ and ‘worker’ etc.

In general, Japanese people seem to have a well-developed sense of hierarchy, which is mostly absent in Australian society, or at least in the circles I mix and have grown up within.

It goes beyond that though.

Relevant also is the degree of intimacy that exists between the people within the conversation and that also conditions the words one uses, the intonation and the tone of the language used.

It is complex.

There is another complexity – 丁寧語 or teineigo.

This is a formal Japanese and it is different to keigo the polite Japanese.

Here is an example:

I say – My name is William

Tameguchi – Bill desu – which means I’m Bill – casual like.

Keigo – Watashi wa ko Bill tomōshimasu – My name is Bill.

Teineigo – Watashi no namae wa Bill desu – My name is Bill.

It is sometimes difficult to discern when to use the Keigo or Teineigo modes (polite versus formal).

It is safe always to use the polite form although you will sound awfully formal.

All part of the process.

What I am learning though is that the Japanese approach this complexity with a sliding scale of tolerance.

When a beginner is just starting out, the locals are very accommodating and will overlook transgressions – like using casual when you should be using polite.

As I noted – err on polite even if you sound a bit stiff.

But as one’s language skills increase and the Japanese detect that you are beyond the beginner stage their expectations similarly increase.

And while they won’t say anything explicit to you in conversation you clearly see from their faces that you are stepping over the line and mixing tameguchi with keigo in the same sentence or group of sentences and thus transgressing.

As I said complex – but a challenge.

A new MMTed development in the wind … coming soon!

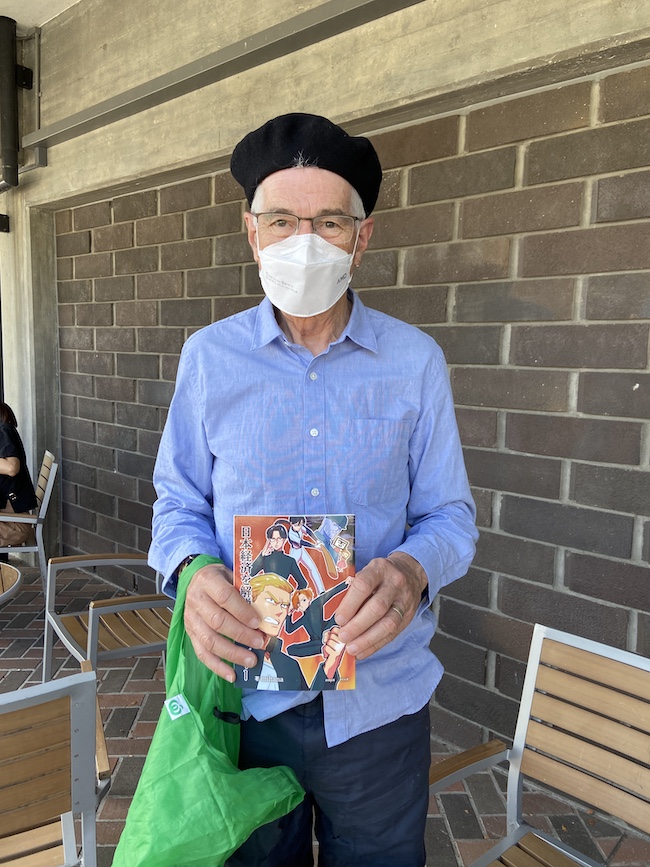

Here I am at a local tea shop – with an outside terrace where I studiously avoid Covid and the bad flu that is around Kyoto at present.

I took my mask off just for the photo – so you could verify it was me reading the manga (-:

I will have more to say about the printed matter that I am holding and reading at a later date – like in a few weeks.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2023 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

So many nuances. That manga looks very interesting.

Certainly great advice.

“Therefore all things whatsoever ye would that men should do to you, do ye even so to them: for this is the law and the prophets.” Mathew 7:12

I am currently on the opposite side of the problem – I work with two brilliant ladies from Hong Kong. Their written English skills would be close to perfect, if they could just get the tenses and participles correct!

For example, they’ll note something like “the client called got the customer on the line”, which native speakers will know is absolutely wrong, but explaining the difference between “got” and “with” in this context is extremely complex – especially if it’s been some decades since you were taught about participles yourself.