These notes will serve as part of a briefing document that I will send off…

No change in monetary easing from Bank of Japan until wages growth increases

The media and the phalanx of mainstream economists from banks etc, the latter of which have a vested interest in interest rates rising in Japan for various reasons, are constantly predicting that the Bank of Japan will relent to the ‘market pressure’ and reverse its current monetary policy stance and fall in line with the majority of central banks. While the concept of ‘market pressure’ is held out as some economic process – something inevitable to do with basic fundamentals governing resource supply and demand – it is really, in this context, just gambling positions that speculators have taken in the hope that the Bank will relent and reward their bets with stupendous profits. So last week, the Bank of Japan announced that it was changing its policy towards Yield Curve Control (YCC), which set the cat among the pigeons again. This is what it was all about.

The speculators have conjured up a sequence of ‘turning points’ in their narrative, after which the Bank of Japan will relent.

Recently, it was claimed that the changing of the guard at the level of Governor would end the ‘easing’.

That didn’t happen.

And on July 28, 2023, the Bank announced that it was changing its policy towards Yield Curve Control (YCC), which set the cat among the pigeons again.

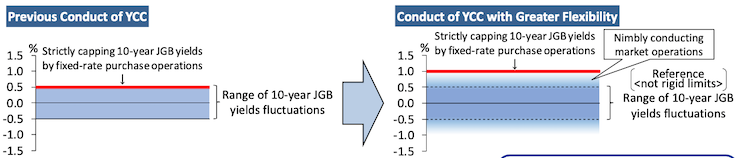

The statement the Bank released – Conducting Yield Curve Control (YCC) with Greater Flexibility – was a very nicely laid out infographic, but failed to appease or satisfy the ‘markets’.

By way of background, I explained the YCC approach taken by the Bank of Japan in this blog post – Bank of Japan once again shows who calls the shots (September 3, 2018).

We know that:

1. Once bonds are issued by the government in the ‘primary market’ (via auctions) they are traded in the ‘secondary market’ between interested parties (investors) on the basis of demand and supply. When demand is strong relative to supply, the price of the bond will rise above its ‘face value’ and vice versa when demand is weak relative to supply.

2. If the demand for government bonds declines, the prices in the secondary market decline and the yield rises.

To understand that relationship, please read this blog post – Bank of Japan is in charge not the bond markets (November 21, 2016) – where I provide a ‘bond yield primer’.

3. Any central bank has the financial capacity to dominate the demand for any specific maturity bond in the secondary markets and thus can set yields.

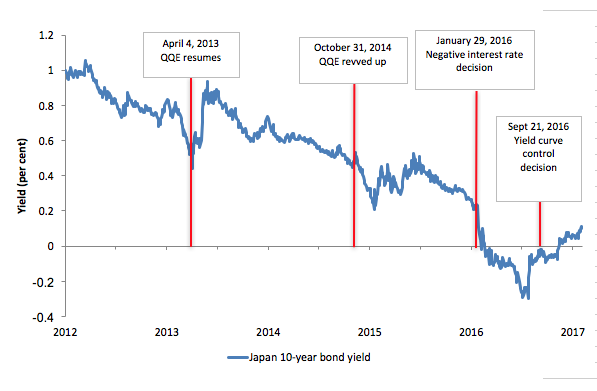

The Bank of Japan has unveiled a sequence of so-called easing measures since it resumed on April 4, 2013 its program of – Quantitative and Qualitative Monetary Easing (QQE) – which involves the Bank entering the secondary JGB market and more recently corporate debt markets and using its endless capacity to buy things that are for sale in yen, including government bonds and other financial assets.

On October 31, 2014, the Bank of Japan announced it was expanding the QQE program.

It would now “conduct money market operations so that the monetary base will increase at an annual pace of about 80 trillion yen (an addition of about 10-20 trillion yen compared with the past).”

Then on January 29, 2016, the Bank issued the statement – Introduction of “Quantitative and Qualitative Monetary Easing with a Negative Interest Rate” – which augmented the QQE program – continuation of the annual purchases of JGB of 80 trillion yen and the application of “a negative interest rate of minus 0.1 percent to current accounts that financial institutions hold at the Bank”.

I considered that decision in this blog – The folly of negative interest rates on bank reserves (February 1, 2016).

The explosion in yields predicted by the financial press did not pan out – the speculative commentary was wrong as usual.

The yields followed exactly the course that Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) predicted – down and then up more as the Bank has varied the scale of the QQE program).

Here is what has happened to the 10-year JGB yields since 2010 to February 6, 2017, with the announcements demarcated by the red vertical lines.

At the September Monetary Policy Meeting (MPM) which was held over September 20-21, 2016, the Bank of Japan’s – Announcement – introduced what they called a “New Framework for Strengthening Monetary Easing: ‘Quantitative and Qualitative Monetary Easing with Yield Curve Control’ (QQE)”.

This approach became clearer when the Bank publicly released the – Minutes of the Monetary Policy Meeting on September 20 and 21, 2016 – on November 7, 2016.

Essentially, the Bank said that it would use YCC to:

… control short-term and long-term interest rates

Not the markets controlling rates – the central bank.

Through YCC, it could control nominal interest rates at all parts of the yield curve and the:

Bank will purchase Japanese government bonds (JGBs) so that 10-year JGB yields will remain more or less at the current level (around zero percent).

The speculators do not control government bond yields unless the government allows them to.

Essentially, the Bank of Japan would engage in:

(i) Outright purchases of JGBs with yields designated by the Bank (fixed-rate purchase operations)1

(ii) Fixed-rate funds-supplying operations for a period of up to 10 years (extending the longest maturity of the operation from 1 year at present)

This means that it will stand ready to buy unlimited amounts of Japanese government bonds at a fixed rate whenever it desires.

The operations of the plan were outlined in this statement – Outline of Outright Purchases of Japanese Government Securities – released on November 1, 2016.

So that is history.

Last week, as noted above, the Bank of Japan made a change to the YCC program.

They indicated that their plan to stabilise inflation around 2 per cent was not yet forthcoming – which was not reference to a higher current rate but was referring to their view that the current rate was transitory and the fundamentals – wage pressure – were such that the inflation rate would fall well below 2 per cent once the transitory factors abated.

As I explained before, here is a central bank that desires much higher wages growth, whereas most central banks are trying to drive unemployment up in order to further suppress (fairly low) wages pressure.

For the Bank of Japan, however, flat wages pressures biases their economy to deflation and low growth, and so they will hold their monetary policy position until wages start growing more robustly.

Their infographic (shown in part below) shows the shift in YCC policy they are now proposing.

Essentially they have lifted the ceiling from 0.5 per cent to 1 per cent and will use their currency capacity to buy bonds to ensure the yields fluctuate in a somewhat flexible band.

The ‘somewhat’ is what has sent the speculators into conniptions.

The Reuters’ headline (July 29, 2023) – Bank of Japan’s opaque policy shift means stronger and wilder yen – captured the sentiment – opaque – what could the Bank actually mean?

The Wasghington Post article (July 28, 2023) – BOJ yields some control, but also throws a curveball – claimed the policy shift represented:

… a small step toward relinquishing its longstanding attachment to ultraloose money.

But then admitted that a world of rising interest rates in Japan “is way off, if it ever happens”.

They then labelled the change “half-hearted” or an “unedifying fudge” as if the Bank was wavering and a little lost.

Wrong.

The Bank made it clear that they would continue to “offer to purchase unlimited amounts of 10-year government bonds daily at a rate of 1%.”

Only the ceiling has changed.

And, yesterday (August 2, 2023), Uchida Shinichi, the Deputy Governor of the Bank of Japan gave a speech to local leaders in Chiba (near Tokyo) on – Japan’s Economy and Monetary Policy.

It was an interesting speech and covered a wide ground.

But the wishers from the financial markets will remain disappointed.

It is clear that the small variation in the YCC program is not seen as a shift from the fundamental position that the Bank has held for some years now.

The Deputy Governor said (among other things):

1. “There are extremely high uncertainties over the outlook for prices, including developments in overseas economic activity and prices, developments in commodity prices, and domestic firms’ wage- and price-setting behavior. The Bank’s assessment is that sustainable and stable achievement of the price stability target of 2 percent has not yet come in sight.”

2. “signs of change have been seen in firms’ wage- and price-setting behavior … we are trying to determine the critical inflection point where firms’ behavior that took root during the period of deflation may change” – in other words, they are looking for evidence that the deflationary mindset that has kept wages growth suppressed is changing.

When that change is detected, they will start tweaking their monetary policy stance.

3. “aim to achieve the price stability target of 2 percent in a sustainable and stable manner, accompanied by wage increases.”

4. “the Bank assesses that the downside risk of missing a chance to achieve the 2 percent target due to a hasty revision to monetary easing currently outweighs the upside risk of the inflation rate continuing to exceed 2 percent if monetary tightening falls behind the curve” – in other words, they don’t want to attack the current elevated inflation with policy shifts that might cause recession and further exacerbate their attempts to get wages growth rising.

5. “the Bank needs to patiently continue with monetary easing in the current phase and support Japan’s economy so that wages continue to rise steadily next year” – they will be guided by wages growth because they consider that essential to ensure inflation stablises around 2 per cent and that the current risk is that inflation will drop well below that once the Covid-Ukraine-type disruptions abate.

On YCC specifically, the Deputy Governor said “that there is still a long way to go before such decisions are made” which was in reference to those who thought interest rates should rise now.

He also reaffirmed that the trigger for a major policy shift would be the wages situation rather than the temporary elevation in inflation.

However, the Bank was also wanting to ‘smooth’ the yield curve, by which they meant that they wanted to keep a stable relationship (within bounds) between returns on corporate bonds and JGBs.

They considered that holding to a tight plus/minus 0.25 per cent band on JGBs (as the YCC policy maintained before a previous modification in December 2022) had meant that “yield spreads between corporate bonds and JGBs widened unnaturally” which had undermined the intended effects of monetary easing on firms”.

In other words, corporate borrowing rates were rising due to “extremely high uncertainties surrounding economic and price developments at home and abroad” and the low JGB yields were becoming an outlier.

Small shift though.

The December shift “had created expectations in the bond markets that the Bank would eventually make responses if problems arose”.

The Deputy Governor, however, made it clear that despite the uncertainties requiring “yield curve control with greater flexibility”:

Needless to say, we do not have an exit from monetary easing in mind.

Conclusion

So there is no hint of a return to the position that other central banks have taken.

The Bank of Japan is firmly committed to providing ‘expansionary’ conditions to encourage growth in wages, which they consider is essential to underpin a stable inflation rate of 2 per cent – their goal.

All the noise around that target created by the pandemic etc is just noise.

Pity the rest of the central bankers didn’t follow suit.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2023 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Professor Mitchell,

The introductory paragraph is cut off at the last sentence: “So last week, after the Bank of Japan announced …” . Your point is clear, but I wanted to let you know.

Best,

Justin

Orthodoxy economists says that level of savings in japan is high and that people dont spend much, so there’s no reason to increase interest rate.

Rafael Isaacs said

“Orthodoxy economists says that level of savings in Japan is high, and that people don’t spend much, so there’s no reason to increase interest rate.”.

Well, more evidence that the national accounts don’t lie. Pity the same can’t be said for the orthodox economists. The savings couldn’t exist were it not for Japan and its central bank supporting deficits.

Yet, these same orthodox economists keep spreading misinformation about governments needing to run surpluses.

If the orthodox economists had their way in Japan 25 years or so ago the level of savings would be lower and consumption spending would be different as well – and not for the better.

But they claim overall that Japan has been going through deflation for a long time, savings are high and propensity to spend is not high and these are the reasons for japan not increase their interest rate even during pandemics with all government spendings