I have been thinking about the recent inflation trajectory in Japan in the light of…

The current inflation trajectory still looks to be transitory

On November 11, 2021, the Bank of International Settlements (BIS) related their BIS Bulletin No. 48 – Bottlenecks: causes and macroeconomic implications – which presents evidence that should help people who are becoming het up about the inflation numbers lately to calm down a bit. On June 8, 2021, the UK Guardian published an Op Ed I had written – Price rises should be short-lived – so let’s not resurrect inflation as a bogeyman – which I stand by. I have been criticised for dismissing the inflation threat and I regularly get E-mails announcing the Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) is ‘over’ and has been proven wrong by the rising inflation rates around the world. Those interventions actually break up my day with ‘humour’ – I am continually amazed how little people know who have such strong opinions. I always adopted the view that you work something out before forming an opinion. In this ‘social media’ era, the working out bit seems to have lapsed and people just jump in. That used to be called blind prejudice. Anyway, the BIS research is interesting and supports my on-going view that the current inflation trajectory still looks to be transitory and the forces that led to the supply bottlenecks will also likely unwind in the other direction to depress price rises.

The supply bottleneck basics

1. Changes in demand and supply is implicated in the rising prices at present.

2. On the supply-side, the pandemic has created:

Bottlenecks in the supply of commodities, intermediate goods and freight transport have given rise to volatile prices and delivery delays.

The bottlenecks have arisen for a number of reasons.

For raw materials, shortages in supply pushed prices up, followed by price falls as supply resumed and/or demand fell.

Shipping costs have risen because “ships have been forced to queue for days to access ports”, which then leads to “clogging distribution across the supply chain”.

Lockdowns have means labour shortages in trucking and air freight, which has pushed up prices.

The contagion effects then move into production where manufacturers have had to slow production to scale with available material inputs.

In turn, retail inventories decline and prices rise to ration demand.

3. The pandemic created disruptions in supply in a number of ways.

Workers could not work.

Asymmetric lockdowns across the globe “disrupted shipping” – meaning that freight could not transit smoothly between ports where lockdown restrictions were different, which led to the queueing of ships, stockpiles of containers in the wrong location, and more.

Importantly, earlier failures to invest in new capacity prior to the pandemic in some industries, meant that as demand fluctuated, capacity was met more quickly.

Running just-in-time systems to minimise short-run costs, has been proven to be inefficient over a longer period, as raw material inventories have been squeezed and productive capacity exhausted quickly by the sudden recovery in demand once the earlier waves of the virus (and the lockdown restrictions) eased.

The point is that the recessions the world experienced in 2020 were unlike the usual cyclical events. A lot of spending was put on hold by restrictions rather than negative consumer sentiment.

Further, the spending shifted towards certain items (like home renovation materials etc) and to on-line purchasing, which quickly altered the demands on supply infrastructure.

The lack of flexibility in shifting supply capacity to meet these very sudden shifts has created these supply bottlenecks.

4. On the demand-side, there is evidence that “rising prices for some items went hand in hand with high volumes”.

So supply was able to meet demand but at higher prices – for example, semiconductor exports.

In part, this relates to “the shift in the composition of demand towards manufactured goods”, which relates to the point I made under (3) above.

The input-output chains in manufacturing are broader than in the services sector.

Given the services sector was hardest hit by the lockdowns, and spending patterns shifted to produced goods, the strain on supply of inputs from ‘other industries’, which supply these manufacturing firms, was sudden and sharp.

Again this relates to point (3) where because produced goods are capital-intensive, earlier failures to maintain growth in productive capacity hit home as the pandemic recoveries ensued.

The point to remember is that the pandemic was a massive, multidimensional disruption that is rarely seen in history.

Major shifts in behaviour were immediate as lockdown restrictions were imposed.

To draw any comparisons between this sudden shifts and a well-planned spending intervention by government in terms of infrastructure building or service delivery reveals a lack of understanding of how things work and are linked.

5. The BIS paper also notes that there was a sudden “behavioural change on the part of supply chain participants”, who started to bring forward purchases to create hoarding stockpiles of materials ‘just in case’.

This is the analogue of the consumers rushing supermarkets in the early days of the lockdowns and buying up all the toilet paper they could get their hands on.

Frenzied buying of this nature exacerbated the supply bottlenecks.

6. Interestingly, the factors that have created these bottlenecks, will also, likely, lead to downward pressures on prices in the coming period.

Why?

The JIT systems – “lean structure of supply chains” – which exacerbated the shortages because firms could not adjust capacity quickly enough, also has convinced firms that they need to invest in expanded capacity quickly, which will considerably enhance supply ability in the future.

Further, the stockpiles that firms have built up will mean that firms will be battling for market share with expanded inventories, and that will put downward pressure on prices.

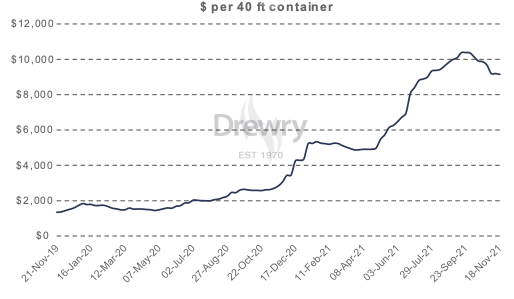

The – Drewry’s composite World Container index – is used by analysts to gauge what is happening with supply-chain pricing.

This graph shows their World Container Index since late 2019.

More specifically, between September and October 2021, the spot price for freight between China and the US fell by 29 per cent.

Similar falls in freight prices between China, Europe and the UK have also occurred.

So it may be that the worst has past and the virtuous impacts, that strained prices early in the pandemic will provide easing influences as recovery continues.

The negative feedback impacts

Supply and demand are also interdependent, a point that Keynes understood but the modern New Keynesian approach fails to grasp.

So when there are supply bottlenecks, production and income generation declines.

The BIS paper notes that this impact depends on:

… whether bottlenecks affect items that are upstream (ie at the start of production chains) or downstream (ie closer to final consumers).

The number of goods impacted is higher if the bottlenecks occur upstream – especially at the outset of the resourcing process

So raw materials are at the start of production.

Semiconductors higher other (“one third of the way down the chain”).

Freight is at the consumer end typically.

The upstream bottlenecks that have arisen during the pandemic have had large impacts – through “output multipliers”.

For example:

… a 10% contraction in world semiconductor production would reduce global GDP by about 0.2%.

And as a result of the bottlenecks arising predominantly in tradeable goods, the impacts have been global.

But substitution is also going on as firms seeks alternative ways of dealing with raw materials in short supply.

For example:

… rising natural gas prices have already seen some electricity firms increase coal power generation … some firms have started to use air freight to circumvent shipping delays.

Clearly, the impact on inflation rates is being observed in the data releases that have been coming out.

The BIS paper talks about “mechanical effects on CPI inflation”.

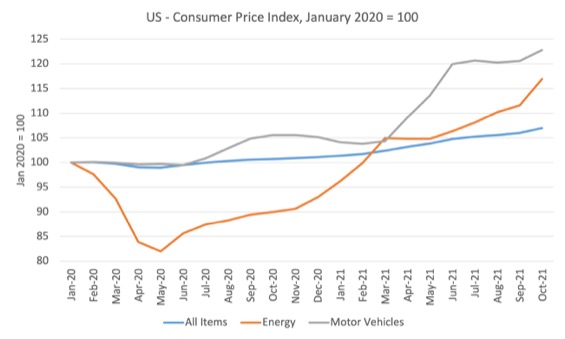

On November 19, 2021, the US Bureau of Labor Statistics released the October 2021 Consumer Price Index data.

The BLS say that:

The Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers increased 6.2 percent from October 2020 to October 2021, the largest 12-month increase since the period ending November 1990. Prices for all items less food and energy rose 4.6 percent over the last 12 months, the largest 12-month increase since the period ending August 1991. Energy prices rose 30.0 percent over the last 12 months, and the food index increased 5.3 percent …

In terms of the ‘All items less food and energy category’:

Used cars and trucks (26.4 percent) and new vehicles (9.8 percent, the largest 12-month increase since the period ending May 1975) were among the greatest risers in prices in this category for the year ended October 2021.

The following graph shows the impact of Energy (weighted at 7.322 per cent of total CPI basket) and New and Used Motor Vehicles (weight 8.163 per cent) on the trajectory of inflation in the US since the beginning of the pandemic.

In the early stages of the pandemic, demand for energy (fuel mostly) fell dramatically and prices tumbled.

As movement resumed, the prices have risen again and given the weight of this item, the overall CPI has also risen significantly.

The BIS paper concludes that:

If energy and motor vehicle prices in the United States and the euro area had grown since March 2021 at their average rate between 2010 and 2019, year-on-year inflation would have been 2.8 and 1.3 percentage points lower, respectively … That said, once relative prices have adjusted sufficiently to align supply and demand, these effects should ease. Some price trends could even go into reverse as bottlenecks and precautionary hoarding behaviour wane. The mechanical effect on CPI could well turn disinflationary during this second phase.

They also rehearse a point I have made regularly – that these bottleneck effects will be temporary unless there is a wage-price spiral propagating mechanism activated.

My assessment is that there is so much slack left in the labour market and trade unions are so weakened by decades of neoliberalism that the chances of a full-blown, 1970s ‘slug fest’ between labour and capital is unlikely.

Stronger segments of the workforce where unions are still active and meaningful may be able to entertain some real wage resistance and push through wage rises, which might stimulate some further price rises.

But I do not think this will be a global possibility.

Further, firms are busily responding to the shifts in demand and the behaviours that the pandemic has elicited and while that “boosts demand in the near term, it raises productive capacity” over time, which will be a depressing force on prices.

What does this mean for MMT analysis?

For the critics who have been hoping for some inflation as evidence that MMT-style analysis is plain wrong, sorry for the disappointment.

The current inflation verifies key aspects of an MMT understanding.

There is nothing at all normal about a once-in-a-hundred-years pandemic (hopefully).

The shifts in demand, the constraints in supply have been large and rapid.

No economy can adjust that quickly without consequence.

The supply constraints that have emerged merely reflect the scale of disruption and tell us nothing about the way an economy responds to properly calibrated fiscal interventions designed to maintain full employment.

It is surprising actually, that prices haven’t risen by more than they have given that large sections of our economies have been shut down, while workers have been given income support in various forms by governments, thus maintaining demand higher than otherwise.

What the pandemic has done for MMT is show that government deficits do not drive up bond yields and interest rates, if the central bank provides supplementary support to the spending increases.

It has shown that ultimately, bond markets can only influence yields if the government allows them too.

It has also shown that there is a huge thirst for government debt – as a form of corporate welfare.

It has shown that governments can spend very large amounts, very quickly, whenever it chooses, without the connotation of ‘running out of money’.

All core MMT propositions, which place our work in contradistinction to the mainstream New Keynesian analysis and predictions.

Conclusion

I remain with the view that these inflation spikes will dissipate in time as the world settles down again – if that settling does indeed occur (and here I am thinking of the up-tick in the pandemic as the Northern Winter ensues).

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2021 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Well, it may be worse, and raising prices are a good crisis not going to waste.

“Corporations are using the excuse of inflation to raise prices and make fatter profits”, says Robert Reich.

https://www.businessinsider.com.au/corporations-using-inflation-as-excuse-to-reap-fatter-profits-reich-2021-11

Pointed out by friend of MMT Cory Doctorow (with more quotes and links),

“Corporate America has a lot of room to absorb prices; across the board, the historically unprecedented fat margins these firms extracted before the crisis have grown. Two thirds of US public companies have increased their profits since 2019. 100 of the top US companies have grown their profits by 50%.

There’s a simple reason companies are able to pass these price hikes onto us: they face no competition. Most industries are dominated by five or fewer companies”

https://pluralistic.net/2021/11/20/quiet-part-out-loud/#profiteering

One thing that has occurred to me is that New Keynesian thinking sees bottleneck inflation and true inflation as the same which, if nothing else, shows that they are not in any way Keynesian. They can’t seem to differentiate the two.

Any consumption price changes at all are to be squashed, and the remarkably effective way of dealing with this problem is to increase welfare payments to bankers and the other ‘outdoor paupers’ in the finance industry.

But asset price rises are fine because that means the same bankers can lend more.

Price is how markets ration scarce goods and services. That’s why we all don’t own a luxury yacht. Those workers that have become scarce (truck drivers) will be able to bargain for higher wages. Those that haven’t won’t and they will be the ones that take the loss this time – because the distributional conflict is resolved by the threat of unemployment.

Yet again it is the same ‘bank and interest payments’ viewpoint that sits at the heart of the mainstream economist’s religion. It’s disappointing to see some of the newer people associated with MMT drifting off down that road – just as Minsky and Lerner did in their later years.

I came across a history of the end of the Gold Standard in the UK over the weekend (“Shocking Intellectual Austerity: The Role of Ideas in the Demise of the Gold Standard in Britain” by James Ashley Morrison) that revisits the events of the period.

The view presented explains that gold ended because the people running the Bank pursued their beliefs in an attempt to bring about a crisis and influence the politicians, not because Keynes persuaded them to change their mind.

The (independent) Bank of England will not put up the interest rate, for the simple reason that the tories won’t allow a further increase in mortgages (they’ve already risen) when there’s so much grief coming down the line as a result of Budget. I foresee a spring election, after Doris replaced.

Morning,

“I always adopted the view that you work something out before forming an opinion. In this ‘social media’ era, the working out bit seems to have lapsed and people just jump in.”

They are selling vacuum cleaners door to door and luxury oils and bubble bath. It is all to do with politics because the world has never been so divided. MMT has shown them to be wrong on just about everything for decades and the inflation mania is just them hanging on by the finger nails.

Remember that these people sold books and talking tours around the country creating fairy tales and called it cutting edge economics. There is no better example than the recent article by James Meadway in the Guardian.

Rail cuts are another sign of the Treasury’s bias against the north of England

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2021/nov/19/rail-cuts-treasury-north-england-chancellor-rish-sunak-no-10

All politics with no critical thought or educating the reader based on the usual political framing and narrative around interest rates, deficits and debt. GROUPTHINK is still strong within the Borg. I’m actually surprised Meadway didn’t throw in we are living beyond our means because of the trade deficit narrative he loves so much. Then he would produced the “full house” of mainstream groupthink.

No mention that Chinese regulations that actually affected coal mines in China. They increased the safety standards in mining that scared the he’ll out of some mining companies to the point that many closed down.

That flowed into the Chinese economy as 70% of electricity is by coal in China. Caused major shutdowns in industrial activity in China. So producing the real resources the West needs to complete their spending plans slowed significantly.

When it comes to shipping what they did manage to produce. In normal times shipping a container from China to the US is $2000 because of lockdown that is now $20,000. It is first come first served a bidding war.

Once they actually get to the ports in the west. Because they have not been upgraded in decades as government spending is seen as the devil and austerity is the bank lobby god. The ports can’t cope and are struggling to find the people who are sitting at home.

Once they get loaded on to the trucks what happens there is we have a driver’s shortage. Because drivers left as the free markets demanded poor working conditions combined with low pay. We Uberised the trucking industry on the back of the free market tooth fairy. Truckers were treated like Uber drivers. When you are paid by the load instead of by the hour. Sitting at a port for 8 hours suddenly turns it into a loss making exercise to deliver the containers so they don’t bother.

What James Meadway didn’t mention ……

a) These sources of inflation have nothing to do with low income families. Who have had been attacked and whose benefits just to eat and heat and pay their rent have been cut.

b) Government spending has to be increased not slashed and needs to be invested in import substitution , the ports , our whole infrastructure to help ease future inflationary episodes and bottle necks. Regardless of borrowing costs as the BOE could just take on the debt. Meadway prefers pump priming and the famous Labour roads to nowhere approach.

c) The tooth fairy free markets does not work. The government needs to regulate how truck drivers and port staff are treated. The logistics monopoly power that port and shipping companies have has to be regulated and curtailed. Rent seekers need to be forced to compete and not allowed to extract rent from a monopoly perch.

d) The city of London needs to be put back in its box.

d) Tell me what can the BOE do to affect the coal production in China ?

Nothing.

e) What can the BOE do to affect the wages of truckers and port staff ?

Nothing

f) What can the BOE do to affect the pricing of shipping and supply chain costs ?

Nothing

Yet, we live with this insane neoliberal globalist belief that if we leave everything alone the tooth fairy will fix it, and the BOE run by the bank lobby by increasing or decreasing interest rates by O.25% The UK will be wonderful.

They could have cancelled HS2 because they were afraid of bidding prices up because under current conditions they can’t get the people and real resources needed to complete the project. Why they are so scared to give the public sector the wage increases they deserve after years of pay freezes.

Politically Conservative voters don’t want the public sector pay rises or wanted HS2 completed because they think their taxes will pay for it. Inflation mania is a way for the Conservative party to give their voters what they want.

It looks like they are going to tinker around the edges of HS2 and put a sticking plaster on the public works and use what people and real resources they already have. Patch up the network instead of a complete rebuild.

Well thought out preparation and well planned projects can allow the government to turn on spending fairly quickly in a downturn and turn it off (or restrict it) in times of high pressure. So it looks like they have restricted it during this supply side shock.

Theresa no need to abort HS2 completely. They can implement effective fiscal policy to meet both longer-term needs of its people but also counter-cyclical responses in a time when recession threated as non-government spending was in retreat. Kept parts of the infrastructure project on the back burner and completed some of it as a fiscal injection response in a down turn instead of digging holes and filling them back up again. Which would have helped with inflation and bottle necks in the future.

On top.if all of that The neo-liberal era has also been marked by a major reduction in Departmental capacity to design and implement fiscal policy – given the obsession with monetary policy and the major outsourcing of “fiscal-type” government services to the private sector.

Many of the major government policy departments in the advanced nations are now just contract managers for outsourced service delivery. Which limited their response to both the pandemic and HS2.

James Meadway is a carpet bomber . Carpet bombs taxes, carpet bombs interest rates and carpet bombs government spending by pump priming so doesn’t see any of it.

“marked by a major reduction in Departmental capacity to design and implement fiscal policy”

A marked reduction in capacity to achieve anything.

You’ve seen the UK Civil Service recruitment process. How good do you think that is as a way of hiring people with the capability to get anything done?

@Neil Wilson

Very interesting article on Britain coming off the gold standard, although somewhat depressing. According to this interpretation, Britain came off the standard largely due to accident and happenstance. It seems almost nobody wanted to stray off the gold standard, not the voters, most of the politicians and certainly not the bankers, it just sort of happened. What if Norman Montagu hadn’t had a nervous breakdown and remained throughout as head of the BoE? What if the political situation hadn’t been misjudged? What if the situation hadn’t been allowed to play itself out? Contrary to what libertarians would have you believe, self interest is not all that common.

The inflation boogeyman has been used to push austerity on the middle and lower classes.

What’s the cost for the ultra-rich?

They keep getting richer, so there is no cost, whatsoever.

The supply of money has grown?

So they get a bit more.

Inflation is a weapon of the class war.

One thing about New Keynesian thinking is that, not only is reducing demand always the preferred way to combat inflation; but, the preferred method to reduce demand is always raising interest rates. Is there anything that raising interest rates would do that increasing financial regulation could not do better?

Yup!…Enough said!!!

MMT would achieve more relevance by refocusing the debate on asset inflation which is real and not transitory, as accelerating asset values actively reshape the vulnerability of the economy let alone impacting on social democracy. Wouldn’t MMT argue against raising interest rates and consequent debt service costs (relative to GDP) which result in lower asset values and higher loan-to-value ratios? Grim outlook for postponing a financial crisis?

@George Whitlam, the only asset price inflation which matters is land (one of the 3 factors of production). It was written out of the economic text books more than a century ago.