In the annals of ruses used to provoke fear in the voting public about government…

Ex German Finance minister deliberately misses the point about the ECB

The German daily business newspaper Handelsblatt published an interesting article last week (September 17, 2020) – Schäuble fordert Debatte über lockere Geldpolitik der EZB – which said that the former German Finance Minister and now President of the Bundestag was calling for a debate on the ECBs ‘loose’ monetary policy. He has circulated a letter and a discussion paper among the new discussion group within the Bundestag, created after the German Constitutional Court had ruled adversely in relation to the ECBs public asset purchase programs. The letter criticises the low interest rate policy of the ECB and the various asset purchase programs conducted by the ECB. It appears to be in denial with the state of affairs across Europe, which are heading catastrophic territory with the second wave of the virus gathering pace and authorities having to face the need for a second lockdown.

Recall that the Bundesverfassungsgericht (the German Constitutional Court) determined in its – May 5, 2020 Ruling – that the Court of Justice of the European Union had “exceeded its judicial mandate” in determining that the ECBs asset purchase program (PSPP) was within the legal limits of the Treaties.

The ruling said that:

… the Federal Government and the German Bundestag violated the complainants’ rights under Art. 38(1) first sentence in conjunction with Art. 20(1) and (2), and Art. 79(3) of the Basic Law (Grundgesetz – GG) by failing to take steps challenging that the ECB, in its decisions on the adoption and implementation of the PSPP, neither assessed nor substantiated that the measures provided for in these decisions satisfy the principle of proportionality.

Proportionality is a ‘principle’ built into the TEU (Articles 5(1) and 5(4)) which relate to the “division of competencies between the European Union and the Member States”.

In this case, the intent of the ruling was to question whether the ECB’s behaviour was commensurate with its stated monetary policy objectives.

It is clear that the Treaties never considered the ECB would play a major fiscal policy role, which in the climate of austerity imposed by the Commission on Member States, became essential if the common currency was to survive.

On the one hand, it has made it impossible for Member States to maintain high levels of prosperity. Member States move between various degrees of crisis as they try to stay within the ‘unworkable’ fiscal rules.

On the other hand, the ECB, which was entrusted with monetary policy, has been forced by the austerity bias to become a sort of de facto fiscal agent, which the Treaties claim (via subsidiarity etc) is the sole domain of the Member States.

This is what the BVerfG is ruling against.

I considered that decision in this blog post – BVerfG decision once again exposes the sham of the Euro system (May 6, 2020) – and the title indicates what I thought about it.

There have been all sorts of compromises proposed to deal with the fall out of the decision, particularly in relation to the conduct of the Bundesbank. But that is not the topic today.

The Bundestag discussion group was set up to work through the problems created by the Court’s ruling for the German government and its central bank.

Essentially, on September 10, 2020, they announced that there would be a quarterly ‘monetary policy dialogue’ – see Deutscher Bundestag vereinbart ausschussübergreifenden „Geldpolitischen Dialog” – which would be a cross-committee discussion within the Bundestag.

The first guest would be “Bundesbank President Jens Weidmann on the subject of ‘The monetary policy strategy of the European Central Bank and its effects, particularly after the judgment of the Federal Constitutional Court on the PSPP bond purchase program'” on September 16, 2020.

Its first meeting was last Wednesday (September 16, 2020) – Weidmann sieht Tiefpunkt überwunden (Weidmann sees the low point has passed) – the Bundesbank boss told the group that “things are looking up again” although the German economy would take a long time to recover from the impacts of the pandemic.

He reiterated that the “inflation rate in the euro area was subdued and remains below the ECB’s target of 2 per cent”.

On the PEPP program, which has been expanded to 1,350 billion euros, he said that while the purchases had departed in proportional terms from the capital key (the amount each member state contributes to the ECB’s capital base and supposedly a regulative proportion for bond purchases) because there have been disproportionately higher purchases of Italian and Spanish government debt (and low purchases of German and French debt), this was justifiable given the scale of the pandemic.

He said that the “Geldpolitik dürfe nicht ins Schlepptau der Fiskalpolitik geraten” (monetary policy should not get caught up in fiscal policy) and that he had a “grundsätzliche Skepsis” (fundamental skepticism) about the massive government bond purchases that the ECB was making.

He said they should be scaled back as soon as possible.

The Germans are always on edge about these matters.

But the discussion paper circulated by Wolfgang Schäuble has some sense as well as nonsense.

It noted that the ECB’s policy instruments had failed to achieve their goals – they did not work (“haben nicht gegriffen”):

Trotz jahrelanger Niedrigzinspolitik, massiver Anleihekäufe mit der Folge übergroßer Liquidität und eines wirtschaftlichen Booms bis Ende 2017 wurde das Zwei-Prozent-Ziel bei der Inflation bisher nicht nachhaltig erreicht. Offensichtlich haben die Instrumente der EZB nicht gegriffen; trotzdem werden sie weiter verwendet …

(Despite the years of low interest rates and massive bond purchases resulting in excessive liquidity and an economic boom by the end of 2017, the two per cent inflation target has not yet been achieved. Obviously the ECBs policy instruments did not work, but they were nevertheless used.)

Clearly the inflation target has not been achieved.

PEPP update

My previous update on the Pandemic emergency purchase programme (PEPP) program was provided in these blog posts:

1. ECB asset purchase programs are the only thing keeping Member States solvent (May 28, 2020).

2. Eurozone inflation heading negative as the PEPP buys up big – don’t ask the mainstream to explain (June 4, 2020).

Note that the PEPP is just an additional bond buying program that the ECB is pursuing.

Its – Public sector purchase programme (PSPP) – by far the biggest program of the four non-PEPP asset purchasing programs has already (by August 2020) accumulated 2,273,588 million euro assets and added 15,150 million euros in the month of August 2020.

Very large in other words.

In terms of the PEPP program, the ECB has cumulative net purchases of 499,876 million euroes by the end of August and purchased 59,466 million assets (mostly Member State government bonds) in August 2020.

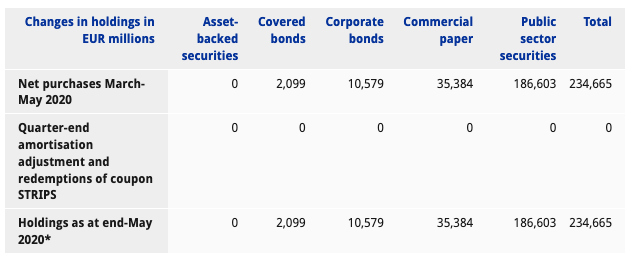

This table gives the break down across the categories of assets purchased.

The breakdown of the private bonds was interesting – mostly commercial paper.

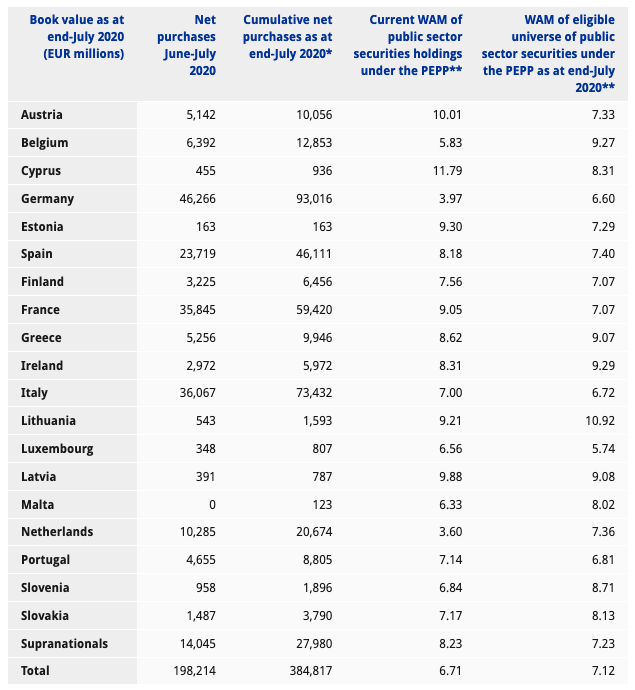

The next table shows the Member State breakdown and the weighted average maturity (WAM) of the purchases under the PEPP.

Unsurprisingly, the ECB has been purchasing a lot of Italian government debt and the maturity profile of that debt is longer than, for example, Germany, where the ECB is buying more short-term debt.

The question of interest though is the extent to which these purchases are deviating from the capital contributions of the Member States to the ECB.

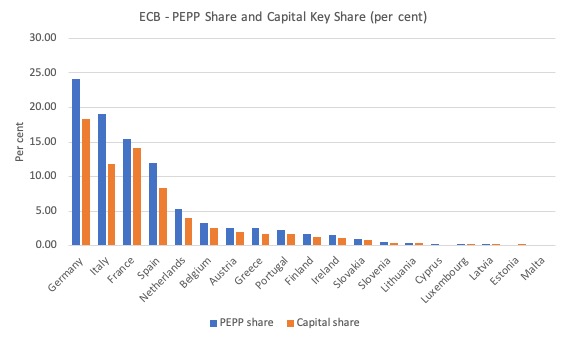

The following graph shows the PEPP shares by Member State – as a percent of the total purchases – from March to the end of August 2020 (blue bars) and the Capital share (orange bars).

ECB purchases of German debt dominates and is above their capital share as is the case of Italy and Spain. Only four Member States are under-represented – Luxembourg, Latvia, Estonia and Malta.

To see this in another way, the next graph shows the percentage point deviation from the capital key of the ECB bond purchases.

Once again, we conclude that there has been massive central bank funding of Member State fiscal deficits – Italy is the stand out – in a deflationary environment.

Not only has there been no inflation but the bond-buying has not driven an expansion in real GDP growth – quite the opposite.

The only conclusion is that this form of aggregate policy intervention is largely ineffective in the face of Member State’s resisting the expansion of their fiscal deficits to adequate levels.

I know that the European Commission has relaxed (for the moment) the Excessive Deficit Mechanism and the strict fiscal rules, but there remains a mentality in Europe that fiscal deficits should still be constrained.

The only effective function that the ECB is performing is keeping the Member States from becoming insolvent, which prolongs the life of the common currency, but little else in that austerity-biased world.

More on that later.

European inflation

In this blog post – Monetary policy has failed – we must reprioritise fiscal policy (February 5, 2019) – I discussed the ECB failure to meet its most basic legal responsibility – to meet its price stability targets.

By way of summary, the ECB’s monetary policy charter requires it “to maintain price stability”, which they define as:

… a year-on-year increase in the Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices (HICP) for the euro area of below 2% … the ECB aims at maintaining inflation rates below, but close to, 2% over the medium term.

The definition is clear enough and certainly allow some latitude around the 2 per cent target in the short run. But, equally, the definition would certainly exclude systematic departures from the target over an extended period.

The latest Eurostat data (September 17, 2020)- Annual inflation down to -0.2% in the euro area – shows that the August 2020 euro area inflation rate had dropped from 0.4 per cent in July to negative 0.2 per cent.

They note that “A year earlier, the rate was 1.0%.”

In some countries there is serious deflation – Greece (no surprise) -2.3 per cent and Cyprus -2.9 per cent.

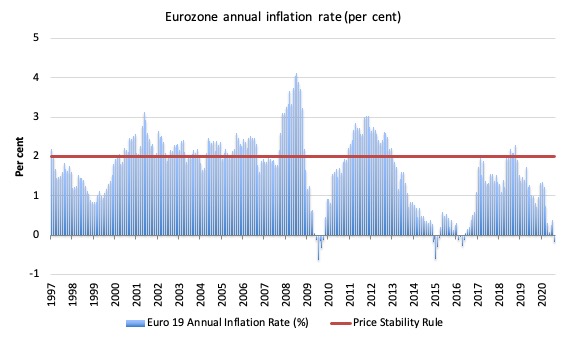

The following graph shows the history of the All-Items HICP [prc_hicp_midx] series since the first month of 1997. The inflation rate is computed as the annual change in the index. The red line is the ECB’s definition of price stability, which

The data shows that the inflation rate has been anything but stable under the watch of the ECB.

And, last week’s news of deflation is on the way only reinforces that message.

How does one reasonably interpret this apparent failure?

The only conclusion that could be drawn is that the ECB has just plain failed to fulfill its stated policy mandate.

In other words, the claims that the euro has been a success in terms of maintaining price stability are just nonsensical.

The behaviour of the data is not surprising to an analyst cognisant with Modern Monetary Theory (MMT).

In the absence of an institutional bias towards inflation (indexation schemes, etc) or a imported raw material (for example, energy) shock, inflation will be low if not negative if aggregate spending growth in the relevant ‘economy’ is weak (in relation to what is required to maintain high pressure and low unemployment).

So the specific lack of correspondence between the actual Euro area inflation rate and the ECB’s price stability target provide us with evidence that the Euro area has been wallowing in a low growth environment, contrary to claims by Euro officials that the euro has been a “historic success” in terms of promoting strong real growth.

But it also reflects on validity of the core ideas of mainstream macroeconomics and the type of thinking that Robert Barro injected into the profession.

Their’s is a fictional world.

Was there a European boom in 2017?

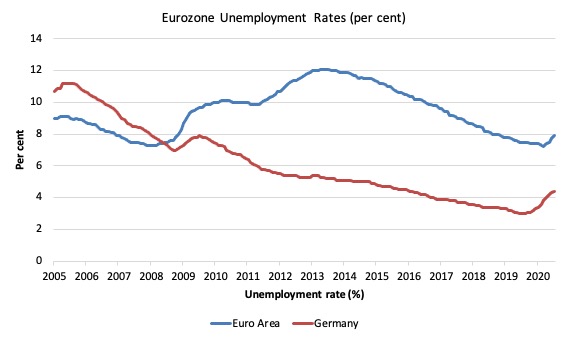

The trajectory of the unemployment would suggest not. A steady decline at best, and, during 2017, still well above the pre-GFC level for the Eurozone (that is 10 years after).

But then Wolfgang Schäuble doesn’t actually exude an optimistic outlook.

Here is the graph.

The point that Wolfgang Schäuble misses or chooses to miss

It is quite clear that the ECB has publicly claimed that its bond buying program was about meeting its inflation target.

For example, on July 3, 2014, ECB President Mario Draghi’s – Introductory statement to the press conference (with Q&A) – announcing the “outcome of today’s meeting of the Governing Council” noted that:

As our measures work their way through to the economy, they will contribute to a return of inflation rates to levels closer to 2% … the key ECB interest rates will remain at present levels for an extended period of time in view of the current outlook for inflation …

… the Governing Council is unanimous in its commitment to also using unconventional instruments within its mandate, should it become necessary to further address risks of too prolonged a period of low inflation.

We could also go back to May 2012 when they introduced the Securities Market Program which started their embrace with large-scale public debt purchases.

It has always been clear that the ECB was pursuing monetary policy – both interest rate setting and the other ‘non-standard’ interventions – with the stated intent of pushing the inflation rate back to 2 per cent on a stable basis.

It is pretty clear they have not been able to have much influence on the evolution of the Euro area price level.

They certainly haven’t been able to achieve an acceleration in the inflation rate.

So, in that sense, Wolfgang Schäuble is correct. The policy tools do not work.

‘Not work’ taken to mean in the context of not pushing the inflation rate to 2 per cent and keeping it there.

This has massive implications for how one assesses the validity of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) viz the dominant mainstream New Keynesian macroeconomics.

The latter has a preference for what they term monetary policy assignment over fiscal policy because they claim that monetary policy is an effective instrument for maintaining full employment and price stability.

The evidence certainly does not support that preference.

But the problem with Wolfgang Schäuble’s conclusion is that it is dead wrong.

Dead wrong taken to mean in the context of what the ECB was actually doing and what all the Eurozone elites were turning their backs on because they knew it was the only way the Member States would remain solvent.

While the ECB and all the European sycophants have steadfastly held onto the narrative that the massive asset price purchasing programs were about maintaining cash liquidity in the banking system, the reality was quite different.

The ‘elephant in the room’ that they refused to acknowledge was that they had to say that to give the impression they were remaining inside their legal Treaty obligations.

The reality was quite different.

They have been basically funding Member state deficits through the ‘back door’ so to speak.

They know they can always keep the bond yields throughout the Eurozone low and convergent (with the German benchmark bund yield). The bond markets, in turn, know that they can purchase the debt of even the weakest Member States with little risk and offload it onto the ECB via its various asset purchase programs.

They make a tidy capital gain if they sell to the ECB.

In this little ‘game’, the ECB breaks all the Treaty rules relating to ‘bailouts’ and worse, then participates in vicious austerity programs (as part of the Troika) to make sure the Member States are ‘at heel’.

Conclusion

Once again the Germans are trying to assert their authority over the ECB and bully it into constraining the only policy intervention that is saving the eurosystem from collapse, by way of insolvency of several Member States.

Its constrictive thinking is really a good reason for Italy and Spain to lead the others out of this mess.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2020 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

The eurozone is such a mess.

As a layman, inclined to think more philosophically than economically, I’ve come see monetary theory as being solely concerned with a fiction called “the economy”–fictional because it considers only the interests of the rich. To the contrary, fiscal theory is concerned with the conditions under which all people, including average people and the even-more-marginalized, must live–something obviously real which we call “society.” Accordingly, the more real we get, the more human we get, and the more MMT makes sense. Forgive me this overgeneralization, but it helps me get a handle on a lot of Bill’s objective analysis and parsing, makes it subjectively meaningful to me. Otherwise, I’d quickly lose the forest for the trees.

It seems to me that the most serious among the many defects of the EU is the presence within it of Germany.

Modern Germany is the lineal descendant of the Holy Roman Empire, of which the first emperor crowned in AD 800 was the Frankish (ie germanic) king Karl known to us English-speakers by his French name (!) Charlemagne. In recent history the reincarnation of that realm was the German Empire, formed out of the North German Confederation following upon its victory over the French second empire in 1870 under Prussian leadership; it lasted until November 1918 when Germany became a republic.

The North German Confederation had contained no fewer than nineteen independent states, of which two (Prussia and Saxony) were Kingdoms and the rest a miscellany of Grand Duchies, Duchies and Principalities – plus three Free and Hanseatic Cities.

How was it ever to be expected that a behemoth with such antecedents, the modern population of which exceeds 83 million, could comfortably be assimilated into a – nominally superordinate – supra-national polity which lacks any government, legislature or tax-raising power of its own whose sole federal organs are a central bank issuing its currency and a bunch of bureaucrats in Brussels purporting to make its rules? The idea is so preposterous that if anyone had advanced it forty years ago in those – unvarnished – terms they’d have been laughed out of court. It only came about through a series of accidents.

Germany itself is a federation to which all those formerly sovereign states ceded their own sovereignty only in recent history: why on earth would such an entity willingly subordinate itself to any other body whatsoever? Clearly Germany was never going to toady to the Brussels bureaucracy but would insist on dictating the rules itself. Its own parliament, constitution and judiciary prescribe the rules it must obey and if that brings it into conflict – as it inevitably must – with the Commission, the ECB and the ECJ – too bad.

The situation is completely untenable.

European sycophants or American sycophants the song is the same.