I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

ABC bias … what might have been

Lat night’s ABC 7.30 Report had a segment titled Australian economy resilient in tough times. It was so bad I was prompted to write to the ABC complaining of their neo-liberal bias. All the commentators were the usual coterie of investment bankers and private consultants all of who have particular vested interests which are not disclosed when they are held out by the ABC as so-called experts! Not one independent researcher was included in the segment. In another world, this might have been the way the show evolved.

I took the liberty of including myself as one of the so-called expert commentators and the only one who could not be accused of representing a commercial interest. This is how the transcript would have read under these new arrangements. All but the commentary from independent expert Professor Bill Mitchell is from the actual ABC 7.30 report segment.

KERRY O’BRIEN, PRESENTER: Canberra and the rest of the nation had to absorb more bad news on the jobs front today, with further retrenchments and warnings from the Treasurer and the Industry Minister that there’s definitely worse to come. But the gloom was offset somewhat by the latest capital expenditure figures which showed a six per cent surge in the December quarter to $25 billion. Such mixed signals help explain why opinion is divided about whether the Federal Government’s massive spending program to try to keep the economy going will have the desired effect, and whether the ultimate bill will be worth it. But if Australians now and in the future find these federal deficits a heavy burden to bear, what then of our major trading partners, whose spending sprees simply dwarf our own. It’s an issue that is posing major heartburn for economies around the world. Business editor Greg Hoy reports.

GREG HOY, REPORTER: It’s a global conundrum. And call it what you like – fiscal expansion, stimulatory packages, economic shock therapy – just how affordable is the Federal Government’s pledge to outlay a total of $72.6 billion in the years ahead to help the economy through the global financial crisis, building the net government debt to 5.2 per cent of gross domestic production or GDP by 2011 to 2012. And ultimately, who will pay?

SAUL ESLAKE, CHIEF ECONOMIST, ANZ: There’s no doubt that reverting to public debt may eventually lead to a modestly higher level of taxes. But compared to the levels of government debt that governments in generations gone by have had to service, what’s in contemplation for Australia over the next few years is quite modest. Moreover, it’s incredibly small by the standards of the public debt that governments overseas are looking at.

PROFESSOR BILL MITCHELL, DIRECTOR, CENTRE OF FULL EMPLOYMENT AND EQUITY: There is no correspondence between the increased outlays and future tax levels. It may be that in the future the Federal Government will want to increase taxation to control overall spending but that will have nothing at all to do with “financing” the increased government spending. The Federal Government is sovereign in its own currency and does not need to finance its spending.

Further, the fact that the Government is planning to sell public debt coincidently as they increase spending leads one who doesn’t understand the way the modern monetary economy operates to conclude that the debt is financing the spending. After all, households borrow to fund spending when it exceeds their current revenue. Drawing and analogy between the issuer of the currency (the Federal Government) and the users of the currency (the households) is false. The reason that the public debt is rising is nothing at all to do with “financing” the increased spending – as I said before the sovereign government does not need to finance its won spending. We really need to get over that hurdle before we can understand what the possibilities are.

The reason the debt is issued is simple. The inflow of net government spending (the deficit) adds to the reserves of the commercial banking system which ultimately shows up in the reserve accounts the banks are required to maintain at the central bank (the RBA). These balances earn below the current market interest rate and so it is not in the interests of the banks to hold any excess reserves. So the banks try to lend these reserves in the Interbank market but because the deficit generates what we call a system-wide excess reserves position, the banks themselves cannot eliminate the excess by shuffling reserves between themselves. In trying though, they begin to drive the short-term interest rate down, which means that the RBA loses control of monetary policy which is expressed in the form of its target interest rate. The only way that the RBA can maintain its target rate is to provide an alternative to the non-market interest-earning reserves held by the commercial banks. They do this by selling government bonds. The sales drain the excess reserves (eliminate the system-wide excess) and allow the RBA to “hit” the target rate. It has nothing at all to do with financing the spending. If the RBA didn’t sell the debt then the spending would still occur but the target interest rate would fall to the level that the RBA pays the commercial banks for overnight reserves.

GREG HOY, REPORTER: Indeed, the Australian Prime Minister is the envy of political leaders around the world according to the Chicago-based economist and advisor to the Commonwealth Bank, David Hale.

DAVID HALE, GLOBAL ECONOMIC ADVISOR, COMMONWEALTH BANK: He does not have to worry about the public debt. He enjoys great freedom to stimulate the economy in the next 12 or 18 months; be it through public spending on infrastructure; be it through tax cuts; be it through other spending programs. Therefore, Australia, I think, is potentially more recession-proof than any other country in the OECD.

PROFESSOR BILL MITCHELL, DIRECTOR, CENTRE OF FULL EMPLOYMENT AND EQUITY: The sovereign government never has to worry about public debt. It can never become insolvent in its own currency.

GREG HOY, REPORTER: But calculating the benefits of a stimulus shopping spree versus the cost of swinging from surplus to deficit, funded for now by selling government bonds, is a macro-econometric headache.

MICHAEL KNOX, CHIEF ECONOMIST, ABN AMRO MORGANS: If you look at the total swing in the budget balance, that’s a swing of around about 4.2 per cent of GDP from what we were saving to what we were spending. Now, the net result of that is, in terms of the modelling we’ve done, is to push up long-term interest rates. So, we think that when these bonds to finance the spending actually come to market, that they’ll push up long-term interest rates in Australia by about 1.3 per cent. They’ll probably be around about five per cent by the end of this year.

PROFESSOR BILL MITCHELL, DIRECTOR, CENTRE OF FULL EMPLOYMENT AND EQUITY: The government bond issues do not fund the deficit spending. That is a completely erroneous understanding of the monetary system. Micheal Knox is similarly miscontrued. When the Federal government was running surpluses it was not saving. It makes no sense to say that the sovereign government is saving in its own currency. It issues the currency at its discretion. What meaning is there to saving up something you can issue at will. None at all. The fact is that when the Government ran surpluses it was destroying purchasing power (and accompanying financial assets) in the private sector. The “money” which the surplus represented were destroyed forever. It didn’t go anywhere other than the trash can.

If the private sector saves (by spending less than its income) it creates a stockpile for future use. This analogy does not apply to the Federal government. It can spend in the future irrespective of what went on in the past. It doesn’t need a stockpile nor does it keep one.

Further, the banker is plainly misinformed about how interest rates are set. The RBA sets the short-term rate which then spreads out over the duration maturities to the long-term rates. The difference between the short-term rate and the long-term rates tends to reflect expectations about risk and expected inflation. It is also true, as explained in my previous response, that net government spending (deficits) actually put downward pressure on interest rates and the bond sales merely restore control to the RBA and allow it to maintain a given short-term rate.

Also, the idea that there is a finite stock of investment funds available and competition between users then allocates them accordingly and increased competition drives up the price (interest rates) is also an incorrect depiction. This is the classical loanable funds doctrine that was abandoned by thinking economists years ago. Banks can extend loans whenever they see a credit worthy customer. Loans are not dependent on prior deposits. Loans create deposits as a matter of accounting. What is also not often understood is that net government spending creates the funds that allow people then to purchase bonds should they wish to store their savings in that form of financial asset. The deficit spending pushes up reserves which then my be converted into bond purchases.

So, in short, the deficits imply nothing about future taxes or future interest rate movements. If the RBA thinks interest rates should be higher in the future then they will be. If it doesn’t think that then they won’t be. This will be independent of the course of the deficit.

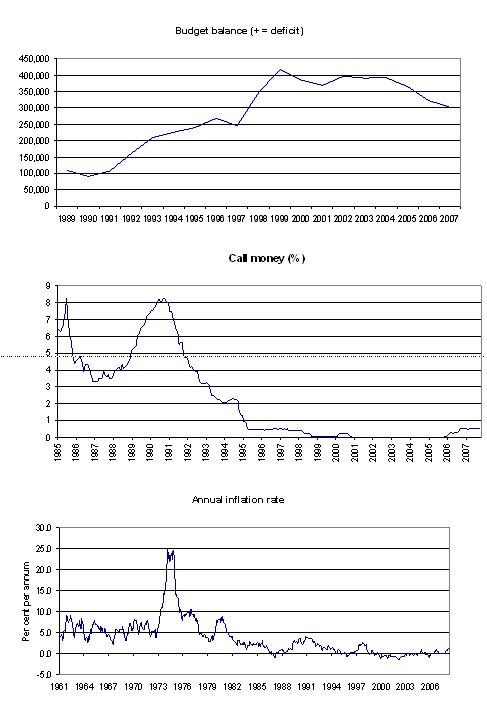

If you need convincing consider the case of Japan. The following slide is from one of my presentations. Japan has been running huge deficits for year yet the Bank of Japan has kept interest rates at around zero and inflation has at times been negative (deflation). The reason: the BOJ has issued less debt than would be required to wipe out the excess reserves in the banking system created by the deficits. The BOJ has then allowed interbank competition (to get rid of the reserves) to drive down the interest rate to around zero.

PETER DOWNES, CENTRE FOR INTERNATIONAL ECONOMICS: Well, the stimulus will add almost a percentage point to employment and reduce the unemployment rate by about a half per cent.

PROFESSOR BILL MITCHELL, DIRECTOR, CENTRE OF FULL EMPLOYMENT AND EQUITY: I probably agree with this. But the stimulus by those estimates is well under what it should be if we are to avoid a major downturn.

GREG HOY, REPORTER: Peter Downes, the former director of macro-economic modelling at both the OECD and the Australian Treasury, calculates the stimulus will work.

PETER DOWNES: On our calculations, the unemployment rate won’t be going anywhere near as high as what the Treasury or what the market is projecting. Now, everybody is at the moment a lot more pessimistic than that – but the impacts on Australia of the crisis, I don’t think, will be as long lasting as most people think.

PROFESSOR BILL MITCHELL, DIRECTOR, CENTRE OF FULL EMPLOYMENT AND EQUITY: If this is true then it means that the fiscal policy intervention will have been the major reason.

GREG HOY, REPORTER: Others question the efficacy of such stimulus spending, suggesting cuts and interest rates have had far greater effect. But if the Australian Government is, as the critics suggest, spending like a drunken sailor, how big will be our hangover relative to our spend thrift major trading partners, such as the big spender of them all and global economic pace-setter, the United States. Its deficit could exceed $2.3 trillion Australian or 11 per cent of GDP this year, as opposed to our two per cent. Its net public debt predicted to reach 60 per cent of GDP by the end of next year. So, sadly, disaster looms, unless extremely painful austerity measures are applied as the country cries out for more government spending as opposed to much less.

PROFESSOR BILL MITCHELL, DIRECTOR, CENTRE OF FULL EMPLOYMENT AND EQUITY: The hangover will be in terms of the residual unemployment and underemployment that will take years to resolve unless there is major direct public sector job creation. The so-called “sprend thrift” major trading partners have to inject more net spending into their economies because the spending gap left by the demise of private sentiment is that much larger. Worrying about the size of the US deficit is a waste of time. It is largely a statistical artifact of the extent of private saving. Governments should only focus on maintaining spending sufficient to fully employ the available labour force and the deficit will be whatever it is. It has not implications for the future well-being of the country how large the deficit is.

To claim a “disaster looms, unless extremely painful austerity measures are applied” is to totally misunderstand the nature of public spending. The disaster is in the lost jobs and lost incomes not the level of public net spending that is required to plug the spending gap.

BARACK OBAMA, US PRESIDENT: I’m pledging to cut the deficit we inherited by half by the end of my first term in office.

MICHAEL KNOX: Very interestingly that’s an exact repeat of a statement made by George W. Bush at the beginning of his second term.

DAVID HALE: Mr Obama will have to confront not just tough decisions on spending but also very unpleasant choices about taxation. There’ll be pressure on him from his own party, the Democrats, to slash defence spending after the increases we had during the Bush years. And he may have to confront some very, very unpopular tax choices.

PROFESSOR BILL MITCHELL, DIRECTOR, CENTRE OF FULL EMPLOYMENT AND EQUITY: This will only be possible if the stimulus package they introduce creates such economic growth that the automatic stabilisers (increased tax revenue and reduced welfare spending) begin to reduce the deficit. Growth will automatically reduce the deficit, other things equal. But to target a 50 per cent reduction independent of the state of economic activity is a mindless exercise and does not reflect an understanding of how things work. The US President would be better focused on getting jobs created including introducing a Job Guarantee and letting the busines cycle, as a matter of course, reduce the size of the deficit.

The US Government will also not have to change tax policy to “cure” its deficit. It may want to revise tax structures to improve equity or to place more or less spending capacity in the hands of the private sector. But those aims have nothing at all to do with addressing a budget deficit. Remember that the US Government does not have a financial constraint because it is sovereign in its own currency.

SAUL ESLAKE: The one advantage that the US has that no other country does is that all of its debt are in its own currency and the US is the source of the US dollars in which the US’s debts are denominated.

PROFESSOR BILL MITCHELL, DIRECTOR, CENTRE OF FULL EMPLOYMENT AND EQUITY: Sovereign governments should never borrow in a foreign currency and all sovereign governments are always the source of their own currency – they hold a monopoly in that regard. There is nothing special about the US in this context.

GREG HOY, REPORTER: So they can print money?

SAUL ESLAKE: In an extreme circumstance they can print money without suffering the consequences that other countries might do in those circumstances.

MICHAEL KNOX: And when we go back to printing money, we hope it doesn’t have the same damaging effects as when that was done in the 1970s, when it produced a whole lot of inflation.

PROFESSOR BILL MITCHELL, DIRECTOR, CENTRE OF FULL EMPLOYMENT AND EQUITY: All government spending involves making adjustments to the bank system – crediting account in private banks – either directly or via recipients of government cheques depositing them. The notion that if the Federal government runs deficits (without selling bonds) then they must be “printing money” is erroneous. That is not the way they spend. Further, the national government spends in exactly the same way irrespective of whatever else happens (that is, whether they change tax rates or sell debt).

The response by banker Knox further reflects the misconstrued monetarist bias in his conception of the way the economy works. All spending, whether it be public or private can be inflationary if it attempts to inject more nominal demand into the economy than there is productive capacity to meet it. There is nothing special about public spending in that regard. If the government continually increased its net spending (deficit) beyond the point that met the spending gap left by the private sector then inflation would be a danger. That is because the economy could no longer respond by increasing real output. But there is nothing inevitable about this. The inflation in the 1970s, was cost-push in nature. Nothing at all to do with deficits. I refer you back to the Japan graphs.

GREG HOY, REPORTER: The UK’s deficit is expected to reach 10 per cent of GDP with no option to print money to ease its inevitable pain.

PROFESSOR BILL MITCHELL, DIRECTOR, CENTRE OF FULL EMPLOYMENT AND EQUITY: The UK government is sovereign in its own currency. It can run as large a deficits as it sees fit.

SAUL ESLAKE: Well, the UK is in a worse position than the United States in two respects. One; its financial sector is relatively much larger than that of the United States. Secondly; that a lot of the obligations that the UK Government is taking on are not in its own currency but, rather, are in foreign currencies.

DAVID HALE: When we get a new government in Britain in 2010, maybe a Conservative government at that point, it’ll have a very difficult first one or two years in office trying to reduce the fiscal deficit, trying to achieve any other goals it might set in the coming election campaign.

PROFESSOR BILL MITCHELL, DIRECTOR, CENTRE OF FULL EMPLOYMENT AND EQUITY: Any British government that targets a deficit reduction without regard to the state of its economy will be foolish in the extreme. Until private spending increases, the deficit will be the only thing driving any semblance of economic growth. I repeat my earlier advice – forget about the deficit. A government that makes the size of the deficit a policy target is irresponsible and will fail. Cutting a deficit through austerity policies when there is high unemployment will worsen the problem. Both the unemployment and the deficit will rise.

GREG HOY, REPORTER: So the British, too, must brace for higher taxes when what they really need is the reverse, as will Australia’s largest trading partners, the Japanese, whose predicament is even worse. With exports plummeting, unemployment rising, nowhere to move on interest rates, a political system in ferment, and the tax base and labour force declining with a rapidly aging population.

PROFESSOR BILL MITCHELL, DIRECTOR, CENTRE OF FULL EMPLOYMENT AND EQUITY: There are no implications for the tax levels in the UK arising from the deficits.

DAVID HALE: I think Japan’s problems are very, very serious, potentially intractable and there’s no way to predict right now exactly how it’ll play out.

PETER DOWNES: Its net debt to GDP ratio is, sort of, in the 90s, like it’s, you know, sort of 100 per cent of GDP.

PROFESSOR BILL MITCHELL, DIRECTOR, CENTRE OF FULL EMPLOYMENT AND EQUITY: Japan needs a larger fiscal stimulus because its private saving rates are so much higher than other nations. Until they increase domestic consumption (perhaps by introducing a national superannuation scheme), deficit spending will have to remain high. Now is the time for the Japanese government to increase its deficit to restore some stability in the economy. Focusing on Debt to GDP ratios misses the point entirely.

GREG HOY, REPORTER: So, in the big picture it seems, the world is an amazing mess.

MICHAEL KNOX: We face short-term crises in Austria, and Greece, in Ireland, the Ukraine, and a number of Baltic countries where the governments teeter on bankruptcy. There are a large number of countries which are in problems and I don’t think your program is long enough for us to talk about them all.

PROFESSOR BILL MITCHELL, DIRECTOR, CENTRE OF FULL EMPLOYMENT AND EQUITY: The world is in a mess. But the banker once again fails to understand the status of a sovereign government. There is no such thing as a sovereign government becoming insolvent in its own currency. It may not be able to pay foreign debts in other currencies but then it will do what Argentina successfully did – default. But in terms of being able to employ its own citizens and pay then in whatever is the local currency, sovereign governments always have that capacity.

GREG HOY, REPORTER: But amidst the gloom and despite its downturn, one glimmer of hope, according to economists we spoke to, is our second largest trading partner, China, particularly after its $600 billion stimulus package.

SAUL ESLAKE: The fiscal stimulus has been massive by comparison with other countries. Chinese government has been talking about and delivering fiscal stimulus on the scale of 13 per cent of GDP. That’s three times bigger relative to the size of their economy to what’s being contemplated here in Australia.

DAVID HALE: I think the numbers are big enough, but this policy action should, by the third or fourth quarter of this year, bring China’s growth rate back to eight per cent. That’s of course very important for Australia.

PROFESSOR BILL MITCHELL, DIRECTOR, CENTRE OF FULL EMPLOYMENT AND EQUITY: The investment figures were surprising but good. Further, the Chinese government seems to be taking the decision that if its export markets are failing then it should use its fiscal powers to divert spending to the domestic economy. This should stabilise their growth rate and benefit Australia through net exports.

GREG HOY, REPORTER: So the aftershocks of the global economic crisis will be many. The Lucky Country, relatively resilient, bobbing about like a cork in heavy seas.

KERRY O’BRIEN: Greg Hoy with a lot of imagery in that report.

PROFESSOR BILL MITCHELL, DIRECTOR, CENTRE OF FULL EMPLOYMENT AND EQUITY: It is sad, Kerry that you had such a biased panel of presenters before I imposed myself on your show.

By the way, Deficits 101 – Part 3 is coming soon.

UPDATE: I sent a comment to the Letters page on the 7.30 Report’s WWW site on Friday morning sometime. While other comments were published they have not clearly decided not to publish my criticism despite publishing others. Perhaps they didn’t like the fact that I had referred their readers to this blog and the alternative universe version of the 7.30 Report interview. Seems to be suppressing debate to me.

Dear Bill,

Is it a case of these people all being incredibly naive, or is it a matter of them each having vested interests in a system which serves them best?

regards. Alan

You say, Mr. Mitchell, that loans are not dependent upon prior deposits.

When the Bank loans money to A, an entry appears on the asset side of the Bank’s balance sheet in the form of a loan and a liability appears in the form of money owed to A. How will the Bank pay out A when he comes to withdraw the funds? The liability will disappear, but not the asset leaving an imbalance.

Is this not correct.

Regards,

Gary Marshall

Dear Gary

1. If A withdraws, his/her deposit at the Bank is debited, as you note, and this is a debit to the bank’s reserves on the asset side, so there is no imbalance.

2. If the Bank doesn’t have sufficient reserves prior to the withdrawal, it automatically receives an overdraft to its reserve account at the central bank’s stated rate as the withdrawal occurs to offset any negative position in the reserve account. The Bank will clear this overdraft later in the business day via additional deposits acquired, borrowing in money markets, or obtaining a collateralized loan from the central bank.

3. The overarching point is that this need to obtain reserves, where it exists, affects the profitability of the loan (since the bank may have to cover a withdrawal of deposits created by borrowing if it cannot acquire additional deposits), not its operational ability to make the loan, aside from capital constraints that can in some instances become somewhat binding (at least in the regulatory sense). In short, there is no loan officer anywhere that first asks the liquidity manager if sufficient funds are available to make a loan . . . the issues instead are the creditworthiness of the borrower and the potential profitability of the loan when comparing interest income received versus paid out on liablities at the margin (and again, potential regulatory capital constraints at the margin).

4. It is only under a gold standard or currency board monetary system in which the Bank would be limited in its lending capacity by its reserves. Otherwise, the process always works as in 1-2-3 above.

Best,

Scott

Hello Scott,

I understand exactly what you are saying. You are speaking of a lag in the time to complete the day’s business.

The parties may negotiate the terms of the loan and the dates of withdrawal prior to the existence of the funds, but the lender at the time of withdrawal or rather at the time of settlement of the day’s business must have the funds on hand to complete the transaction.

If the funds are not on hand at the time of withdrawal, which always comes with a risk, the lender may borrow as you say from a prospective depositor, the always expensive central bank or another bank at settlement time.

So Mr. Mitchell may be correct, but there is a grave obligation to ensure that there are funds to be had when they are called upon. Banks will not just approve loans when reserves are tight because a credit worthy customer shows up. Ignoring that obligation may cost a bank far more than the profits it stood to make on the loan.

Regards,

Gary Marshall

Dear Gary,

“So Mr. Mitchell may be correct, but there is a grave obligation to ensure that there are funds to be had when they are called upon.”

But such funds are always available at stated policy rates. The grave obligation belongs instead to the central bank to ensure smooth functioning of the payments system (in the US, about $2.5 trillion settled each business day via bank reserve accounts). That’s why such overdrafts (or equivalent arrangements) are provided automatically by every central bank not operating under a gold standard or currency board (in the US, for instance, any payment sent via the Fed’s payment settlement system is automatically completed whether the sender has a positive balance or not) and often at little to no cost (intraday overdrafts in reserve accounts are nearly free in the US). And, to your point about the lag before the end of the day’s business, that’s also why for central banks there is a grave obligation to necessarily accommodate the aggregate demand for overnight balances at stated policy rates.

“Banks will not just approve loans when reserves are tight because a credit worthy customer shows up.”

Yes they will, if the benefits of the loan are believed to be greater than the cost of financing liabilities at the margin (again, the cost of which is essentially set by monetary policymakers).

“Ignoring that obligation may cost a bank far more than the profits it stood to make on the loan.”

Again, there is NEVER a shortage of reserves to meet such obligations . . . they are always at the very least made available at stated policy rates.

Best wishes,

Scott

Hello Scott,

Lets say that the Bank has assets and liabilities of $100 each. A borrower comes in seeking a loan at some rate over a 5 year period . It is approved and the assets and corresponding liabilities of the Bank rise by $10, the asset in the form of a loan and the liability in the form of the funds deposited to borrower’s account, to $110 each. Now the borrower arrives to collect his money.

If the Bank has funds, on the asset side money reserves decline by $10 as do liabilities when the borrower takes his money.

If the Bank has no funds, it cannot give the borrower his money. The Bank can either convert an asset to money sending us back one step or it can borrow the funds from some person or organization, i.e. acquire a depositor.

Either way, the funds had better be there when the depositor arrives.

If the borrower issued a cheque on the account, there will be a delay in clearance.

When the time of settlement arrives, the Bank if without reserves would show a money position on its asset side of -$10 for a total asset position of $100. The borrower’s liability would be erased and the total also $100. The Bank must now acquire a depositor, a person, firm, or central bank, to complete payment of the $10 to the claimant bank.

Are we agreed?

That a bank may arrange the financing subsequent to the agreement of terms for the loan matters little. Barring an asset sale, a deposit in an equivalent amount had better be there when the borrower arrives or his cheque is presented for settlement.

There are 2 problems.

The overnight markets fund overnight and very short term needs. The banking business consists in matching assets and liabilities. It would be very foolish for a bank to fund a loan of 5 years in the overnight markets. Were it to fund its mid to longer term loans with money from the overnight markets, there could and probably would be a lot of trouble when an inordinate number of depositors showed up to make withdrawals.

Second, the overnight markets failed to operate in any normal way not too long ago. Libor rates soared. Never is not a word to associate with collapse in the overnight markets.

The official rates charged by central banks are never really their actual rates. There are conditions imposed and negotiations performed that can make the official rate quite a small fraction of the actual rate. Central banks rarely lend much in the overnight markets. Most lending is done by member banks. This has often made me wonder how such small players can supposedly control interest rates within and without the short term money markets?

Regards,

Gary Marshall

Hi,

Love your work. I have a passing intesest in economics. I am actually an IT guy, but have been reading micro economic stiff from mish and Dr Keen for some time. I have no real education in economics, but the following absolutely resonates with me because it has a always been a logical problem about how this works and I could find an answer that actually made sense

“The reason the debt is issued is simple. The inflow of net government spending (the deficit) adds to the reserves of the commercial banking system which ultimately shows up in the reserve accounts the banks are required to maintain at the central bank (the RBA). These balances earn below the current market interest rate and so it is not in the interests of the banks to hold any excess reserves. So the banks try to lend these reserves in the Interbank market but because the deficit generates what we call a system-wide excess reserves position, the banks themselves cannot eliminate the excess by shuffling reserves between themselves. In trying though, they begin to drive the short-term interest rate down, which means that the RBA loses control of monetary policy which is expressed in the form of its target interest rate. The only way that the RBA can maintain its target rate is to provide an alternative to the non-market interest-earning reserves held by the commercial banks. They do this by selling government bonds. The sales drain the excess reserves (eliminate the system-wide excess) and allow the RBA to “hit” the target rate. It has nothing at all to do with financing the spending. If the RBA didn’t sell the debt then the spending would still occur but the target interest rate would fall to the level that the RBA pays the commercial banks for overnight reserves.”

So really the only problem I have in understanding is what happens at the borders. I.e the methodology about what happens when a foriegn entity buys soveriegn debt. I understand that this is still in soveriegn denomitations , but I am a litte confused about how this all works. Can someone give me an simpified model of this ??

Love your work, and am at a complete loss why “reality” is not taught at university. In my industry this would be unacceptable at best , not sure why your industry is any different