In the annals of ruses used to provoke fear in the voting public about government…

Italy should lead the Member States out of the neoliberal Eurozone dystopia

The widely read German news site, Spiegel Online, published an amazing article last week (November 1, 2018) – Italy Doubles Down on Threat to Euro Stability – which confirms to me that very little progress has been within the Eurozone by way of cultural understandings since the GFC. That, in turn, tells me that the monetary union will not be able to get out of austerity gear and is now more exposed than ever to breakup when the next crisis comes. The current Italian situation is the European Commission’s worst nightmare. It could combine with the ECB and the IMF to bully Greece partly because of the size of the Greek economy but also because they had the measure of Tsipras and Syriza. They knew the polity would buckle and become agents for their neoliberal plans. But the politicians in Italy may turn out to be a different proposition – one hopes so. And Italy is a large economy and one of the original accessions to the Community. So the stakes are higher. But what the Commission is demanding of Italy in the present situation of zero economic growth and massive primary fiscal surpluses is totally irresponsible. It will not even achieve the stated Commission aims of reducing the public debt ratio. The likelihood is that the Commission’s strategy, if they succeed in bullying the Italian government into submission, will push the ratio up further. And meanwhile, Italy wallows in a sort of neoliberal dystopia. Italy should lead the other Member States out of this neoliberal disaster.

The contention in the Spiegel article is that:

Fears are growing that the euro crisis may soon return. Italy could spark a chain reaction if it doesn’t yield to the European Union’s demand that it rein in its planned deficit spending. Concern is rising in Brussels and on the financial markets.

So, Italy is to blame. That is the German view.

They report that the European Commission decision to force Italy to revise its fiscal plan within three weeks was:

… was unprecedented in the history of the European Union and a humiliation for Italy.

The Italians appear to have responded with some bluster, with Lega leader Matteo Salvini demanding that “The lords of the spread should step aside”.

The Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte was quoted as saying:

The more I study the draft budget, the more I like it.

The fact is that the fiscal plan drawn up by the new government will “fulfill election promises”. That is, the Italian people clearly voted in favour of the policies and the intervention of the European Commission merely highlights the anti-democratic nature of the European Union and its institutions.

There is more to it than that though and I will analyse whether the Commission’s intervention makes any economic sense below.

The Spiegel Online article is firmly on the side of Brussels, surprise surprise.

It writes:

As a member of the Euro Group, which governs the common currency, Italy agreed to submit to its rules. Previous governments in Italy signed treaties that still apply to their successors. And when the Italian government breaks these rules, it jeopardizes not only the well-being of its own country, but also that of the entire currency union.

Sure enough. But a new government can reject those rules and push for new bargains.

But Spiegel Online believes the Italian government’s demonstration of its intent to pursue the will of the people via its fiscal plan is simply “blackmail”.

Italy is cast as a “monetary time bomb in the middle of the Continent”.

It claims that an “‘Italexit’ would have devastating consequences — not only for the country itself, but also for economies across the eurozone.”

The standard line in other words, which is wheeled out whenever a nation seeks to assert any democratic intent, and is designed to create an irrational fear and prevent volition.

I considered all the cases in my 2015 book – Eurozone Dystopia: Groupthink and Denial on a Grand Scale – and concluded that Italy would be far better off out of the Eurozone than it is staying put.

There would be transition costs, which might be significant, but once the adjustment was made the future would be much brighter than it is under the common currency.

And, at least Spiegel Online admits that:

The euro crisis never really went away, it was just obscured by the ECB’s cheap trillions. Indeed, the crisis could come back at any time if financial markets lose confidence, if investors retreat or if speculators start betting against individual countries. And, as such, against the euro.

That is the reality.

It was only the ECB that prevented insolvencies occurring across many Member States in 2010 and again in 2012.

The common currency has only survived because the the ECB has been systematically breaching the Treaty rules, although claiming otherwise, and the Commission has turned a blind eye.

The fact is that the ECB has been funding fiscal deficits since May 2010 and while they can claim they have only been buying trillions of euro of government bonds as a ‘liquidity management’ operation, the truth is obviously otherwise.

Spiegel Online is clearly trying to sheet all the blame home to Italy.

They claim a pending crisis is:

… because a country like Italy doesn’t follow the rules.

They are silent on the on-going current account surpluses that Germany has been running, which have been well in breach of Eurozone rules.

The German external surpluses (three year average) have risen from 6.2 per cent of GDP in 2012 to 8.4 per cent in 2017 where the maximum allowed under the Macroeconomic Imbalance Procedure is 6 per cent of GDP.

Perhaps if Germany spent more domestically, the other Member States would not need to stimulate their own domestic demand quite as much.

It is ridiculous to isolate Italy in this current period and accuse it of undermining the Eurozone.

Last week’s national account data reveals how poorly the overall Eurozone economy is performing. That has nothing much to do with Italy and everything to do with the poorly designed monetary system which requires an austerity bias under its rules in defiance of the responsible use of fiscal policy.

Spiegel Online also run the intergenerational unfairness argument – that the rising debt incurred to fund the current generation will mean “that their children will have to repay these debts someday.”

And they write that:

Those who argue that Italy needs to boost the purchasing power of its people at the expense of future generations to trigger an economic upswing are overlooking the country’s significant structural deficits …

[and] … the risks of the runaway national debt growth …

We will see below that this statement is largely false.

Spiegel Online uses terms like a “stubborn child” to describe Italian government members:

… how do you raise a stubborn child who finds punishment encouraging?

A morality play with demeaning overtones for Italy.

The point is that the European Commission is stuck. They can insist on austerity even though the Italian fiscal plan is within the Stability and Growth Pact fiscal thresholds.

But they are now dealing with a large economy and with a government that has been sceptical of Europe all along.

This is not Syriza they are planning to bully.

The Commission is clearly hoping that the bond markets will push up the yields on Italian government debt and bring the government to heal that way.

But that pushes Italy to the brink and the outcomes will be less than predictable.

So why the crisis?

On the face of it, the revised fiscal plan presented by the new Italian government only proposed a fiscal deficit of 2.4 per cent of GDP in 2019 and then harsh cuts in the deficit after that.

Remember this is the overall final fiscal balance we are talking about, which includes interest payments on public debt.

The 2.4 per cent of GDP figure is obviously well within the Stability and Growth Pact threshold of 3 per cent.

But under the 2012 Fiscal Compact, which is a “stricter version of the Stability and Growth Pact”, enforces a “a structural deficit not exceeding a country-specific Medium-Term budgetary Objective (MTO) which at most can be set to 0.5% of GDP for states with a debt‑to‑GDP ratio exceeding 60%”.

So it is not just the 3 per cent threshold that matters under European law.

The European Commission’s claim is that the Italian government proposed deficit of 2.4 per cent of GDP is too large to ensure it makes progress on reducing its public debt ratio, which stands at around 131.8 per cent of GDP.

On May 23, 2018, the Commission published its – Assessment of the 2018 Stability Programme for Italy – and concluded that:

1. “Italy is currently subject to the preventive arm of the stability and Growth Pact (SGP) and should ensure sufficient progress towards its MTO” (Medium-Term Budgetary Objective).

2. “As the debt ratio was 131.8 % of GDP in 2017, exceeding the 60 % of GDP reference value, Italy is also subject to the debt reduction benchmark.”

3. “Due to Italy’s prima facie non-compliance with the debt reduction benchmark in 2016 and 2017, on 23 May 2018 the Commission issued a report under Article 126(3) TFEU analysing whether or not Italy is compliant with the debt criterion of the Treaty. The report concluded that the debt criterion as defined in the Treaty and in Regulation (EC) No 1467/1997 should be considered as currently complied with, and that an EDP is thus not warranted at this stage.”

They signalled that they would assess the “compliance” once new data came out – viz. the new government’s fiscal plans.

They also claimed that the economic recovery in Italy had “strengthened” and the economy would grow by 1.5 per cent in 2018.

Some empirical reality

The most recent Eurostat GDP data is now available for the September-quarter 2018 and shows a generalised slowdown in the Eurozone and zero growth for Italy.

To achieve the Commission’s May 2018 estimate of 2018 Italian GDP growth, Italy would have to grow by a near-impossible 1.4 per cent in the final quarter of this year.

The “2018 Draft Budgetary Plan (DBP) of October 2017”, the work of the previous Italian government, had factored on the fiscal balance declining to 0.8 per cent of GDP in 2019, based on the 1.5 per cent growth target.

The reality is that the GDP target will not be achieved.

Far from strengthening, the GDP trend is flattening to negative.

Which means that the cyclical impacts on the fiscal balance will be to push it into higher deficit territory and means that original target in the DBP is not only unnattainable but is also irresponsible to try to reach.

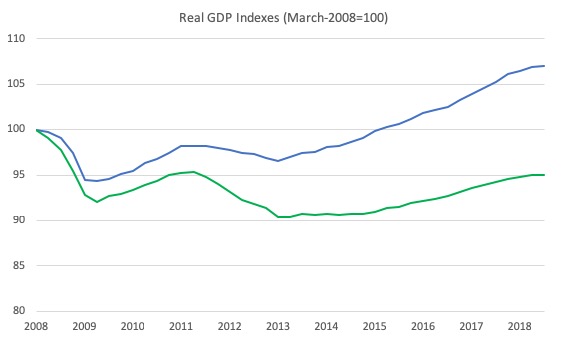

Here is the comparison between the evolution of the GDP for Eurozone and Italy from the March-quarter 2008 peak before the crisis.

The Italian economy is now 5 per cent smaller and cannot be seen as having ‘recovered’ in any sense of that term.

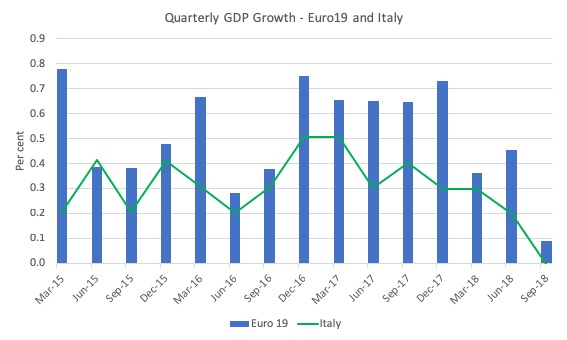

The next graph shows the quarterly growth rates for each from the March-quarter 2015 to the September-quarter 2018.

Italy is now at rock-bottom again as the rest of the Eurozone also slows considerably.

The quarterly growth rate for Italy has been declining since it reached a rather tepid peak (O.51 per cent) in the March-quarter 2015.

That should satisfy you that my estimate of the impossibility of Italy going close to the Commission’s May 2018 estimates is sound.

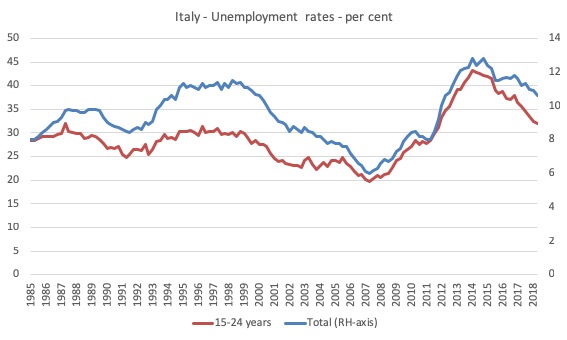

Now consider the labour market situation which is characterised by persistently high unemployment in total and for youth and all the problems that accompany that situation – flat wages, increased poverty rates, precarious jobs and the rest.

The next graph shows the total and youth unemployment rates from the March-quarter 1985 to the June-quarter 2018.

There is no sense that Italy has recovered from the GFC.

The fact that the youth unemployment is still around 32 per cent (rising from a low of 20.4 per cent in the June-quarter 2007, means that a generation of youth will be missing the essential opportunities to transit smoothly from school-to-work and gain necessary work experience as a precursor to a more secure adult life.

The impact of the austerity inflicted on Italy over the last many years will resonate for generations to come.

And these are real costs, not the confected ‘debt burden’ that is usually claimed to represent violations of intergenerational equity.

We can expect the unemployment rate to start increasing again as growth has slumped to zero.

And remember, unemployment is just the ‘tip of the iceberg’.

For more on that point, please see the blog post – If we don’t, it won’t and won’t need to … (October 5, 2009).

With that data in mind, it would be counterproductive to impose increased austerity onto Italy.

Public debt dynamics

And here is one reality, that is mostly overlooked by the financial market commentators who only focus on the aggregates.

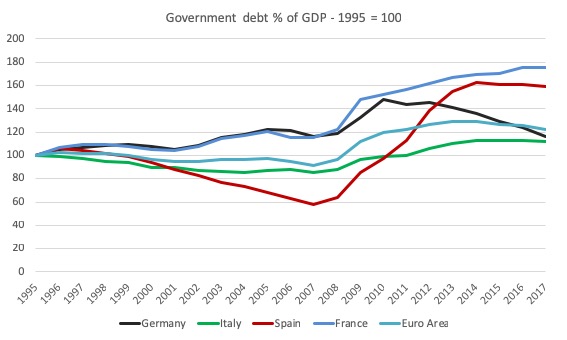

The first graph shows the evolution of the public debt to GDP ratio in France, Germany, Italy and Spain from 1995 to 2017. The indexes are set at 100 in 1995.

So the public debt ratio for Italy has risen by 12.2 points over that 22 year period, whereas the ratio for Germany has risen by 16.6 points, France 75.6 points, and Spain 59.0 points.

The Euro Area debt ratio overall rose by 22.4 percentage points.

In fact, as the next graph shows, Italy has experienced one of the lowest shifts in its public debt ratio since 1995.

So when Spiegel Online talk of the “the runaway national debt growth” you know that is a lie and discloses the motivation for the article.

That motivation is certainly not to correctly inform their readership.

Moreover, while the previous graph allows you to appreciate that the change in the public debt ratio since 1995 has been modest for Italy, the next graph demonstrates it more clearly.

The reality is that Italy’s public debt ratio rose in the 1980s and has been fairly stable ever since. And that has been part of the problem.

Under the convergence criteria to access Stage 3 of the common currency process under the Maastricht agrement, Italy was forced to impose withering fiscal austerity from the mid-to-late 1990s.

That austerity has produced the relatively poor GDP growth that Italy has endured.

The debt ratio is likely to rise anyway if the austerity is enforced because the denominator (GDP) will decline faster than any debt retrenchment under current conditions.

The European Commission economists must know that.

They must know that it is counterproductive in terms of the way they have laid out the problem in their assessment (link above) to force Italy to further cut domestic spending.

And that means the whole farce is a power play and an enforcement of ideology and has nothing much to do with the economics of the situation.

The economics of the situation would – undoubtedly – recommend a much higher fiscal deficit than the new Italian government was proposing.

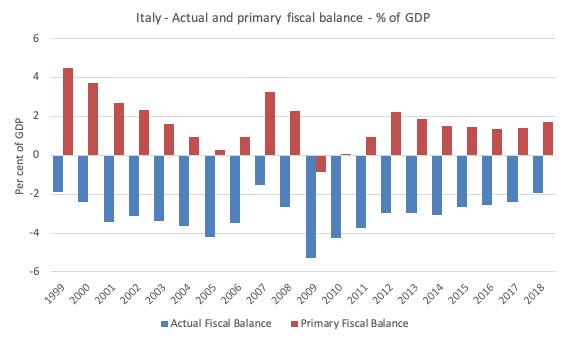

Fiscal Balance dynamics

And here is another reality, that is mostly overlooked by the financial market commentators who only focus on the aggregates.

While the overall fiscal deficit in 2017 was 2.4 per cent of GDP, the interest servicing component of that deficit was 3.6 per cent of GDP.

Meaning that primary fiscal balance was in surplus by a considerable margin (1.2 per cent of GDP).

Remember that the primary fiscal balance is Total spending less interest payments on debt less taxation revenue.

Italy has been running a primary fiscal surplus of varying proportions (averaging over 1.7 per cent of GDP) for some years now.

The next graph shows the actual and primary fiscal balance (using data available from Istat (Istituto Nazionale di Statistica)).

It is hard to construct Italy as being ill-disciplined with respect to its fiscal policy settings.

Far from it.

The claim about Italy has always been that it must run a large primary fiscal surplus to ensure the debt doesn’t ‘snowball’ out of control.

The claim argues that with low growth and the danger of high inflation, if Italy attempted to run smaller primary surpluses, the debt would start to accelerate, especially if interest rates started to rise faster than the inflation rate.

The problem with that sort of reasoning is that the other way to stabilise the public debt ratio is to achieve faster rates of growth and the primary surpluses militate against that opportunity.

That, in turn, means that Italy is stuck in a sort of dystopia – low growth, persistently high unemployment, sluggish wages growth, increased poverty rates, and increasing social instability.

The politics of that sort of dystopia are unstable.

Italy simply must exit the Eurozone to escape that dystopia.

In relation to the large interest servicing component of the overall fiscal balance, some might argue that these interest payments, currently running at around 4.3 per cent of GDP are a source of stimulus, given they represent public income flows into the non-government sector.

The problem is that a significant proportion of these flows are going to the ECB which holds over €560 billion of the Italian government debt about 18 per cent.

Italian-based investors hold around 70 per cent of the outstanding Italian government debt. The non-Eurozone holders of the debt comprise around 5 per cent of all outstanding debt.

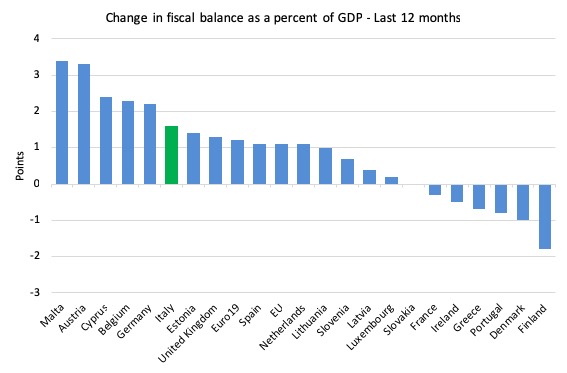

The contractionary nature of the fiscal position in Italy is shown in the next graph, which captures the change in the fiscal balance over the last 12 months (as a per cent of GDP).

A positive change indicates the deficit is falling.

Italy has endured a significant contractionary fiscal shift over this period, which, in part, is the reason its growth rate has ground to zero and is heading into recession states.

A final way of understanding the Italian position is to consider the ‘cyclically-adjusted primary fiscal balance’ (as a percent of potential GDP).

The cyclical adjustment process attempts to create a measure of the discretionary fiscal position independent of the automatic stabilisers.

So this means the cyclical effects on spending (welfare payments) and tax revenue arising from the economy being away from ‘full employment’ are netted out of the fiscal aggregates.

This measure is taken from the IMF and is likely to understate the degree of contraction.

For more on that, please see the following blog posts:

1. Structural deficits – the great con job! (May 15, 2009).

1. Structural deficits and automatic stabilisers (November 29, 2009).

So the process involves assuming a full capacity benchmark level of activity where the impact of the automatic stabilisers (cyclical component) is zero.

At that benchmark, government spending and tax revenue is then compared and that gives the ‘structural’ balance.

The following graph shows the measure for Italy and compares it to the same measure for the ‘Advanced economies’.

A positive result indicates a contractionary position.

The harsh austerity imposed as part of the convergence process in the late 1990s is clear and this killed economic growth and locked Italy into the high debt-low growth dystopia.

Even during the GFC, the Italian government was still running a discretionary contraction and that position has intensified in the ensuing period.

It is hard to see the Italian economy growing at any sensible rate sufficient to reduce its elevated levels of unemployment with this fiscal position.

Conclusion

While the European Commission is attempting to bully Italy into ‘playing by the rules’, the obvious point is that the rules are biased against prosperity.

Human societies cannot endure prolonged austerity and the pathologies that accompany it (elevated unemployment, rising poverty, flat wages, social breakdown).

Italian youth face a bleak future if this situation continues.

To alleviate the crisis, which will come as bond markets push up the yields they are prepared to pay to take on Italian governemnt debt, the ECB will have to intervene, just as it did in June 2012, when a similar situation arose.

How that intervention is constructed – the ‘spin’ – will not alter the reality.

The only thing between Italian insolvency and continuing within the Eurozone will be the central bank.

The uncertainties are what role the Commission will take in the ‘game of chicken’ and whether the Italian bravado persists.

I hope the Italian government holds its ground and forces the Commission into an embarassing retreat.

Italy needs a much larger deficit than 2.4 per cent at present but even the Government’s fiscal proposal for 2019 is better than what the Commission is demanding.

The latter must know that its demands are forcing Italy towards recession. For them, ideology and ‘discipline’ is privileged above all else – even the people of the continent.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2018 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

To be fair to Der Spiegel, their main economics commentator/columnist Thomas Fricke on the German online site has pretty much the same opinion as you here. So they seem to publish a range of opinions.

You will have to put the articles through Google translate to get the gist of it.

http://www.spiegel.de/wirtschaft/soziales/italien-panik-eu-kommission-macht-alles-schlimmer-a-1233986.html

http://www.spiegel.de/wirtschaft/soziales/italien-panik-warum-deutschland-wieder-helfen-muss-kolumne-a-1235200.html

@Matt Usselmann:

Indeed, the two opinion pieces strike a different tone, than the usual sado-monetarist credo one is used to out of the German press.

However, I have a major concern with the wording in one of the two articles. The title literally translates to “Italian panic – why Germany must help again”. My concerns are twofold:

a) The author is equating Germany with the EC/EU. However big the influence of Germany in the decision-making out of Brussels is, there are still other members involved. This freudian slip accurately mirrors the conception of a German financial dictate over Europe many a smaller EU member share, but in my opinion it lets other members of the hook by putting all the blame on the “easy-to-hate” Germans.

b) The concept that Germany needs to “help again” is risible, because no real help was ever provided and if at all it was the ECB who came up with the “funds” and not the German taxpayer as the tabloids like to portray. Furthermore, Fricke speaks helping “again” as if the crisis was coming back when in reality it was never gone. Only the danger of “contagion” for the states “that matter” was contained at the expense of the little ones burdening the load.

From what I hear on almost a daily basis here in Germany, the concept of the “swabian housewife” is alive and well on the right AND the left. It makes it very difficult to justify investments in infrastructure and services in Germany and impossible to conceive of other “less financially stable” members to do so.

The fact that the CDU electorate seems to welcome a Fredrich Merz (BlackRock manager, big finance darling) as a succesor for Merkel, because the party became “too leftwing” clearly indicates that at least a huge part of the electorate and politicians has learnt nothing out of the neoliberal Merkel years and thinks that even though “the patient” has been getting worse and worse due to the treatment, a mere doubling down on the dosis will get him through.

Great read as usual. Just a quick question. How will the ECB’s bond buying program that is said to end this December effect Italy? Would I be right in assuming it will hurt the economy further?

Dear Bryan (at 2018/11/05 at 9:09pm)

That is the point. If the ECB refuses to buy Italian government debt then there will be a so-called ‘market solution’. That will be a crisis and either Italy will back down or it will face insolvency.

best wishes

bill

Hermann, regarding the Italian panic article, I wondered something similar. Who did the author think would be in on the ‘solution’? Re the Swabian housewife, neoliberalism must be the most successful propoganda campaign in history. Hardly anyone anywhere seems to be able to look past the bullshit. Moreover, the propaganda is reinforcing incompetence as a job solution, and to a certain extent psycopathic traits. Since this would seem to be unsustainable, one wonders why it hasn’t collapsed by now. To say that it is supported by those who benefit from it doesn’t quite explain its persistence, I think. And surely, hardly anyone believes what comes out of a mainstream economist’s mouth any more.

Did Merkel really have to go because she was too left wing? If so, that’s ridiculous.

@ larry:

“Did Merkel really have to go because she was too left wing? If so, that’s ridiculous.”

For the sake of simplicity, yes. The more detailed explanaiton is that she ultimately became a victim of her own success (ten of the last fifteen years at the head of a big coalition). Despite her unabated catering to the interests of the big financial and industrial players in Germany, the rise of the AfD is attributed to a sense of “pivot to the middle” by both the CDU (that would be from the right to the center, hence the “she’s too leftwing” argument) and the SPD (from the left to the right in this case). I guess it remains in the eye of the beholder whether it was Merkel’s CDU or the SPD who compromised their positions the most in order to mantain the big coalition alive. What is not up for discussion is that the SPD had embarked in its own demise, long before the big coalition, with their neoliberal “Agenda 2010” under Gerhard Schröder. Also, Merkel was Germany’s darling just up to the “migrant crisis” of 2015. Ironically, that little piece of semi-humane political move became her undoing, since the right flank of the party was wide open for an attack given the previously mentioned pivot to the middle during the years of the big coalition. A more careful observer will note that the coalition remained on a steadfast neoliberal curse, so if any pivoting took place by the CDU, it was merely on the grounds of those social subjects, like the admission of the migrants in 2015.

Since this is all to complicated for your regular revanchists, racists and retrogrades, they simply summarized it as Merkel and the CDU having become “soiled in red and green” (links-grün-versifft). It is also an explanation, alas not a justification, for the attempts of the CSU (CDU’s bavarian sister party) to recover those voters with a harsher right-wing rethoric. Without success.

@Bill: From where I stand, Italy kinda holds all the cards in this unnecessary mexican stand-off, doesn’t it? Either the EC/EU/EZB yield, or the Italians take everybody down with them. Are teh Italians not aware of this, are they too scared to be pushed out of the finacial union or am I missing something else?

Best Regards

Thanks, Hermann. What is happening in Germany is more than a little disquieting.

Hermann,

Translingual or Freudian slip?:

A more careful observer will note that the coalition remained on a steadfast neoliberal curse (= Kurse!)

Apologies for the humour there, your English is at least a hundred times better than my German!

‘hardly anyone believes what comes out of a mainstream economist’s mouth any more.’

I think you are being over optimistic there, Larry. Even if there is an assumption of deceit, very few have got to the point of detecting WHERE the untruths actually lie (inadvertent pun!).

Hermann can substantiate this: I can remember a German minister (can’t recall name) well over ten years ago, that the word austerity (austeritat?) had a deep resonance culturally for Germans (Schwabian Housewife?) yet the Tories (coalition) sold it in the UK very successfully as a dehumanising of the poor for not working hard enough. SImilar to the Harz reforms Bill has written about. I think Germany even uses the expression ‘Job Centre’ which since the 1980’s in the UK (via Steve Bell) became known as the ‘Joke Centre.’

I read the same comments in the Financial Times: no money/printing/Zimbabwe/Venezuela/Bond market vigilantes/devaluation etc and this from a supposed ‘educated reader’ .

Also, Larry, I’m beginning to think that the persistence is largely due to fear and inertia, a fear of change and a media that props up that fear.

@Simon Cohen,

Don’t forget the enormously malign and organised influence of well-funded neoliberal lobbyists and so-called think tanks operating on politicians, journalists, and social media.

Taxpayers’ Alliance, Adam Smith Institute, Institute of Economic Affairs, CBI, IoD, etc etc, plus all the US versions, who also contribute to their funding. A large part of their raison d’être is to promulgate this pernicious ‘government as household’ nonsense for a variety of self-serving political and economic motives, mostly to do with paying as little tax as possible, and keeping the population cowed and fearful.

Best, Mr S.

“Even if there is an assumption of deceit, very few have got to the point of detecting WHERE the untruths actually lie (inadvertent pun!).”

That is true, which is why there are no progressive parties going anywhere, but the fact remains that no one takes it as gospel anymore. Just like most Christians pick and choose what they want to believe out of the bible, right-wing voters give no importance to the American or Italian deficits. Without a leftist counterpoint, it will keep collapsing into nationalist mercantilism until people realize that’s not going to work for them either and we come full circle.

I think that a person in Italy with any savings is glad that he/she is a part of the Eurozone and don´t have the savings in the domestic currency. Based on the historical development of the exchange rate German Mark/Italian lira his/her savings would have been now in the lira currency valueless – http://fxtop.com/en/historical-exchange-rates-graph-zoom.php?C1=DEM&C2=ITL&A=1&DD1=01&MM1=01&YYYY1=1953&DD2=05&MM2=11&YYYY2=2018&LARGE=1&LANG=en&CJ=0&MM1Y=0

Larry is right. Neoliberalism is not a model of economic reality but an ideology shoved down our throats by a strategic global indoctrination strategy. If anyone is interested in a detailed account of how early neoliberal ideas grew out of Austrian university economics departments as the Habsburg Empire declined, and how it was promoted with huge amounts of American money funnelled through organisations such as the Rockefeller Foundation and the Mont Pelerin Society, this is pretty good. http://www.hup.harvard.edu/catalog.php?isbn=9780674979529

@Jiri Jansa

If Italy had never joined the Euro (which is presumably the premise of your counterfactual), holders of Italian Lira would still find them useful for goods and services produced in Italy itself, would they not? What would the exchange rate against the German Mark have to do with anything not produced in Germany?

Isn’t that the whole point of a floating currency?

What are you trying to get at with your comment?

@Steve Hall

I’m partway through Slobodian’s work and am enjoying it very much. Among other things it puts paid to the notion popular in certain circles that “neoliberal” is merely a slur.

@ Simon Cohen

More of a simple typo: The word I meant was “course” 🙂

However, even German is a second language to me so I do get English and German mixed up quite a lot.

As to the whole “love of austerity” issue in Germany, I always had this theory that it had to do with the protestant work-ethos, however, it’s almost as if the catholic states are more into it (see “swabian housewife”, “schaffe, schaffe Häusle baue’! work, work and build a house! “)

I definetly believe there is some ethnic element there, since enjoying life is particularly frowned upon when it comes from one of those lazy “Südländer” (southeners), but it’s not like there is manifest love for the french “savoire-vivre” either way.

I’m afraid that neolberalism will have to literally die off, as in the public figures and academics most tightly associated to it will have to pass away in order to make place for anything else to follow. Some of the grassroots movements in the US give me some hope, although here in Germany I have found the youth to “be older” in their thinking than I think I could ever grow to be. I guess Lenin was on to something when he said that if in the context of a social revolution Germans were to storm a train station, they’d make sure to buy a ticket first.

Best Regards

Hermann, your Lenin comment about Germans and a train station is hilarious. Makes my morning.

@HermannTheGerman @larry

Excellent from Vlad. Thanks for sharing it. made my day too.

@eg

Yes, people can shift to the goods and services produced domestically, under the assumption that these products/services are of the same quality/variety/attractiveness, if the products exist at all.

I am for example from the Czech Republic (part of the EU, not part of the Eurozone) and Eurozone membership would mean for me (my savings) safeness that I don’t lose purchasing power for German/Dutch e.t.c. goods. If my currency would be depreciating (either by the decision of the central bank, or by government running for markets excessive deficits) at the same pace as Italian lira did in its history, I would definitely be worse-off, since I can’t shift to domestically produced goods, some (most) of these products just don’t exist. And it is the case of Italy too.

Look at the graph of Spanish Peso – http://fxtop.com/en/historical-exchange-rates-graph-zoom.php?C1=DEM&C2=ITL&A=1&DD1=01&MM1=01&YYYY1=1953&DD2=05&MM2=11&YYYY2=2018&LARGE=1&LANG=en&CJ=0&MM1Y=0 – it is the same story. Part of the Spanish society (those with the same productivity as Germans had) were during the history worse-off, because part of their productivity (that they could have turned into the consumption of German goods/services) disappeared through the currency depreciation. Now, under the euro currency, these people are safe. At least for these people the return to the national currency would be a step back.

Jiri Jansa:I think that a person in Italy with any savings is glad that he/she is a part of the Eurozone and don’t have the savings in the domestic currency.

Italians saved a lot under the lira too. Italians with savings put them in banks or bonds that paid high interest rates. (Which drove inflation, not fought it.) So in addition to eg’s comment:

(a) The correct figures to look at is how much a lira invested at a normal, government bond interest rate would have grown to over some period, versus how much a mark or euro would have grown to. People don’t hide their savings under mattresses. Remember how Warren Mosler made a pile of dough – things were so crazy, driven by completely irrational doubt in the Italian government and the lira (as in the above linked misleading graph) that Italian government bonds were paying more than what banks were, more than what you could borrow lira from in banks.

(b) Based on the historical development of the Italian economy vs the German or the Italian or European economy especially under the yoke of the Euro, Italians in an alternate universe who still save in lira would be much, much happier, because their better jobs and investments in a much more productive society would have paid a lot more lira into their bank accounts (more even in dollar or mark or Euro terms) than they would under the economic destruction of the Euro & austerity. Interest or prior saving is not the only source of monetary income or wealth.

This is mindblowing stuff.

A lost decade… 10 YEARS WASTED.

Junk economics.

So democracy, and political and economic self-determination can go hang, as long as the kind of people who hanker after a Merc or BMW can be get their satisfaction?

I suppose it’s because their friends all drive Porches…

Meanwhile, back on earth, those with no jobs or savings – in any currency – continue to suffer the iniquitous ravages of supra-governmental imposed neoliberalism. Marvellous!

Mr Shigemitsu: So democracy, and political and economic self-determination can go hang, as long as the kind of people who hanker after a Merc or BMW can be get their satisfaction?

That is an accurate description of a very common perception that Jiri Jansa expressed. But the perception is wildly at odds with reality and logic.

Generally speaking, or very, very clearly in the case of Italy, which has suffered enormously under austerity, the Euro and completely irrational deficitphobia and obsession about meaningless fx valuations the choice is not between the sufferings of the poor and the Merc or BMW for the would-be rich, but a stark one between shared prosperity without the Euro and austerity and shared misery with it.

The general choice has been for “shared misery”, based on carefully fostered economic illiteracy and innumeracy. Everybody gets poorer under austerity, without MMT (= economics that is not an insult to one’s intelligence). The only reason for austerity is class war – the already really rich don’t care about more wealth and money, they want to maintain their position on top relative to everybody else. They do this by sabotaging the economy, by bamboozling those who hanker for a Merc or BMW.

Austerity and the Euro might in some case mean you get your Merc or BMW a little earlier, while your currency is artificially strong and before the inevitable Euro-caused crash occurs. But then your car gets repossessed because you default on your payments. At worst, MMT & currency sovereignty lead to you getting your Merc a month or two later. But then trading it in for a Porsche, just when your Austerian Eurozone alternate reality self is getting his Merc repossessed.

Anyways, for Italians, what’s wrong with Ferraris, Lamborghinis or Maseratis?