I have been a consistent critic of the way in which the British Labour Party,…

Prime Minister Corbyn should have no fears from global capital markets

It is clear that the British Tories are looking like the tawdry lot they are as the infighting over the leadership goes on, more often rising to the surface these days as wannabees circle the failing leader Therese May. Her performance at the Tory Annual Conference was poor, and I am not referring to her obvious difficulties with the flu (or whatever it was). I have been stricken with the flu since I left the US a few weeks ago and occasionally struggled for a voice as I gave talks every days for the 2 weeks that followed. It is obvious there is little policy substance in the Tories now and it is only a matter of time before she is ejected. At the same time, the British Labour Party leadership is showing increased confidence and are better articulating a position, that is resonating with the public. They are even starting to look like an Oppositional Left party for the first time in years and I hope that shift continues and they drop all the neoliberal macroeconomic nonsense they still utter, thinking that this is what people want to hear. A growing number of people are educating themselves on the alternative (Modern Monetary Theory, MMT) and demanding their leaders frame the debate accordingly and use language that reinforces that progressive frame. And, in that context, it didn’t take long for the mainstream media to start to invoke the scaremongering again. It is pathetic really. The New York Times article (October 5, 2017) – Get Ready for Prime Minister Jeremy Corbyn – rehearses some of these ‘fears’. It is also true that the Shadow Chancellor has expressed concern himself about these matters – without clearly stating how a sovereign state can override anything much the global financial markets might desire to do that is contrary to national well-being.

The article noted the train wreck that the Tories Annual Conference became – “half-empty … even the stage fell apart … letters fell off the party’s latest lackluster slogan behind her … a disastrous address … [by May herself] … Conservatives are in free-fall, and the degree to which Mrs. May’s days as party leader are numbered.”

We can agree with all that. It was like a surreal comedy watching any news coverage of the Tory’s conference.

The article also notes that at the Brighton Labour Party Annual Conference, confidence was high and the “references to the party leader Jeremy Corbyn as ‘the next prime minister’ sounded not just like peppy campaign talk but a tangible scenario.”

Fringe events at the Conference “routinely saw snaking queues”. Our event organised by Prue and Peter was a big success in terms of crowd numbers and seeming enthusiasm.

It is pretty clear that if there was a national election now, Labour would probably triumph. It would certainly reflect the growing anti-establishment (neoliberal) revolt that is underway across all nations.

In many countries, it is the right-wing parties that are giving voice to this revolt – unfortunately.

Such is the moribund state of the traditional social democratic left parties, which has deserted their missions to advance the fortunes of the weak and the poor, not to mention the rest of the working class, that extremists from the right look reasonable to electorates.

When we were in Spain the week before last, a major street march occurred in Andalusia with thousands calling for jobs – jobs not basic income. It was the Right that organised this march.

Many on the left have disappeared into their own irrelevancy and think it is somehow clever and progressive to concede that the government no longer has any responsibility or can increase employment.

Instead, they advocate ‘frugal’ dollops of basic income to shut people up – keep them consuming (just) – in other words, they have swallowed the neoliberal line hook-line-and-sinker about the incapacity of currency-issuing governments to create work for all those who cannot find it elsewhere.

We are told this will unleash a creative blitz among all these unemployed people who only yearn to paint, sing, play, relax, drink coffee, and discuss philosophy in corner bars all day. Fu$k me! The Spaniards, like all societies yearn for jobs and secure incomes.

Most have more modest ambitions in life than to become the next Ernest Hemingway or Pablo Picasso.

But I heard the basic income refrain as much as I heard the grand scheme for a global democracy from the mouths of the Left over the last 3 weeks.

But I rarely heard any macroeconomic statement associated with these grand plans and solutions that made any sense at all.

What I did hear on that front was the usual neoliberal gobbledygook – the lies about deficits being unsustainable, causing inflation, causing the currency to lose all value, the ever increasing debt burden, and the rest of it.

I have a good head of hair. And I am thankful for that because it gets frustrating listening to smart people with otherwise progressive values and visions being duped by the mainstream neoliberal economics lies.

Which brings me back to the New York Times article cited above.

It recognises that Labour is now more than an opposition – and is actively preparing for government.

So what are the issues?

1. A run on the pound.

2. Capital flight.

3. A civil service that sabotages Labour’s policy plans.

4. Inexperienced shadow ministers.

5. Add free trade agreements with so-called Investor Dispute Resolution Mechanisms embedded.

The usual suspects in other words.

The same issues that killed of Labour’s progressive policy positions in the mid-1970s and not only paved the way for Thatcher’s terrible period in office, but also, internally, gave oxygen to the even more terrible Tony Blair and his mindless Blairites, who are still lurking within the Parliamentary British Labour Party.

The same issues that led Francois Mitterand to abandon a credible progressive program in 1983 and implement his disastrous austerity turn with Jacques Delors, the alleged Socialist, turned mindless Monetarist, at the helm.

The same issues that I heard repeated often during our speaking tour over the last three weeks.

It is about time, progressives came to terms with these issues and realised that there are always alternatives. The idea of global capital markets closing down a democratically-elected government is a TINA strategy employed by the neoliberals when they get desperate and long for power themselves.

The New York Times says that the “team” of “shadow chancellor, John McDonnell”:

… has met with “various people, asset managers and others, quietly and privately,” and also is looking at what might happen in the event of the party’s victory and “war gaming” possible scenarios, including a run on the pound or capital flight.

So lets dissect that a bit.

First, there is a widespread belief that global finance markets can shut down a nation through the foreign exchange markets.

This sentiment is, of course, a lasting hangover from the 1970s when the British Labour Party claimed in 1976 that it had run out of money and had to borrow from the IMF.

It is a resonating theme among the Left – that somehow, these global capital markets are stronger than a sovereign state.

So the question that has to be dealt with in progressive ranks is why do they still limit their aspirations as a result of this erroneous fear.

I dealt with this in detail in this blog – Addressing claims that global financial markets are all powerful.

It is true that if governments do nothing and allow ‘hot’ money (short-term speculative capital flows) to flow in and out at will then the hedge funds will have a field day and will treat the national well-being as an irrelevance in their quest for yield.

But, in reality, national governments, which issue their own currencies have a range of options, all of which, largely, overcome the power of the global financial markets.

The first thing that we need to do is to distinguish Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) where a foreign investor provides funds to a productive enterprise in another nation, from Foreign Portfolio Investment (FPI), which represents foreign investments in a nation’s financial assets which bear no interest in an underlying productive activity in the real sector of the economy.

FDI might take the form of building a factory, purchasing land for a firm to locate to, or providing plant, equipment, and skills to aid an firm.

Clearly, once this investment is in place, the notion of capital flight becomes difficult to sustain. Productive capital is in situ. It is not a speculative asset. It usually represents a long-term commitment to the growth process of the nation involved.

A nation that maintains a rule of law, has stable government, develops a skilled labour force and has strong investment in public infrastructure is attractive to FDI.

But the fixed-in-place nature of the assets created by FDI provides workers with opportunities should the owners abandon the capital. Argentina in the early 2000s demonstrated that if the owners abandon their enterprises, workers can take control and continue producing if legal approvals are forthcoming.

Esteban Magnani’s 2009 book (the original text was in Spanish and came out in 2003) – The Silent Change: Recovered Businesses in Argentina – documented experiences of “worker control” where factories are “recovered” by various worker organisations after the capitalist owners abandon them after insolvency.

[Reference: Magnani, E. (2009) The Silent Change: Recovered Businesses in Argentina, Buenos Aires, Editorial Teseo.]

He talks about establishing a “more horizontal form of democracy” beyond the typical notions of “representative democracy” where workers know from their experiences how to take control of their workplaces.

There is a great quote from Naomi Klein (from the movie The Take) where she is out the front of the “Brukman factory from which the workers had been evicted” and various opinions were being aired as to the best way forward.

She said:

The idea of this round-table, that so-called intellectuals and journalists should offer theories about how the working class should organize and fight, is both offensive and dangerous. This idea is responsible for a lot of what’s dysfunctional about the Left today. If there’s anything to be learned from these surprising Brukman women, it’s that the working class already knows how to organize and fight. In Argentina and around the world, original, creative, effective direct action is way ahead of intellectual leftist theory.

The Brukman factory is a “textile factory in … Buenos Aires … currently under the control of a worker cooperative” under the recovered factories movement.

It was a central ‘battle ground’ between the owners who abandoned it and the workers. The state sent troops and police in on behalf of the capitalists but through collective action, supported by a solidaristic working class, the Brukman workers retained control of the factory they occupied and as far as I know they continue to operate.

See article from April 24, 2003 – Argentina’s Luddite rulers – for more on the occupied factories movement.

But all that aside, there is a clear distinction between FDI and the other category of capital flows, Foreign Portfolio Investment (FPI)

FPI includes purchases of shares, corporate and government bonds, and other local currency-denominated assets which are typically easier to liquidate than assets created by FDI. Real estate is included in this category if held for speculative purposes, although it is less liquid than the array of financial assets that the ‘hot’ money is attracted to.

Clearly, this capital can be withdrawn very quickly and can be the source of financial instability.

Capital controls function to limit the extent of the currency depreciation when a currency is under attack from ‘hot money’ speculators.

If targeted to short-term capital transactions (‘hot money’) they counter the speculative flows that might destabilise an exchange rate and force a nation to run down its foreign exchange reserves.

In February 2010, the IMF released a research paper – Capital Inflows: The Role of Controls – where they argued that under certain circumstances “capital controls … is justified as part of the policy toolkit to manage inflows”.

The IMF concluded that short-term speculative surges can compromise sound macroeconomic management – by pushing the exchange rate up and undermining trade competitiveness.

They also acknowledged that:

… large capital inflows may lead to excessive foreign borrowing and foreign currency exposure, possibly fueling domestic credit booms (especially foreign-exchange denominated lending) and asset bubbles (with significant adverse effects in the case of a sudden reversal).

FDI which “may include a transfer of technology or human capital” can “boost long-term growth”, but the flows associated with FPI – “such as portfolio investment and banking and especially hot, or speculative, debt inflows – seem neither to boost growth nor allow the country to better share risks with its trading partners”.

Another IMF article (June 2016) – Neoliberalism: Oversold? – concluded that short-term capital flows have questionable legitimacy and that:

Among policymakers today, there is increased acceptance of controls to limit short-term debt flows that are viewed as likely to lead to-or compound-a financial crisis. While not the only tool available-exchange rate and financial policies can also help-capital controls are a viable, and sometimes the only, option when the source of an unsustainable credit boom is direct borrowing from abroad.

Which brings into question why a nation would ever allow unfettered FPI.

Capital inflows that manifest as FDI in productive infrastructure are relatively unproblematic. They create employment and physical augmentation of productive capacity which becomes geographically immobile.

So an incoming British Labour Government has many tools available to it under law to curb the destructive impacts of these short-term speculative FPI flows that do nothing to advance long-term well-being of the people.

The imposition of country-by-country capital controls can help eliminate the destructive macroeconomic impacts of rapid inflows or withdrawals of financial capital but may not be sufficient.

Outright prohibition is one option.

For example, China prevents foreign funds from investing directly into its capital market. It also has quotas on the use of short-term foreign debt that its domestic banks can engage.

Other forms might include required fixed deposits to be made at the central bank of some proportion of the any foreign currency borrowing by domestic firms.

If we adopt a progressive view that the only productive role of the financial markets should be to advance the social welfare of the citizens then it is likely that a whole range of financial transactions, which drive cross-border capital flows, should be made illegal rather than controlled through capital restrictions.

In this context, capital controls may be an interim strategy while the nation sorts through the legislative tangle that would be involved.

This approach would best be introduced on a multi-lateral basis spanning all nations rather than being imposed on a country-by-country basis. The large first-world nations should take the lead. However, given that such leadership is unlikely to be forthcoming a single nation could still act unilaterally in this regard.

Local banks should play no role in facilitating the entry of speculative short-term flows. In this context, the only useful thing a bank should do is to faciliate a payments system and provide loans to credit-worthy customers.

These approaches are unlikely to impact on the willingness of investors to provide FDI as long as the nation has stable government, contractual certainty via the rule of law, and a growing economy with a skilled workforce.

Local tax rules can impact on FDI but that is another story again.

Despite the claims to the contrary, governments impose such controls because they are effective.

The retort is that the financial markets will always subvert capital controls, but the reality is different. Speculators know full well that such controls stop their damaging behaviour.

As Dani Rodrik noted in his Op Ed (March 11, 2010) – The End of an Era in Finance:

Otherwise, why would investors and speculators cry bloody murder whenever capital controls are mentioned as a possibility?

While it is usually claimed that imposing such controls would automatically cut a country off from access to international capital markets, plunging the nation into autarchy, the experience of various countries that have imposed capital controls in recent years disproves this claim.

Indeed, the evidence shows that countries that employed constraints on surging capital inflows fared better than countries with open capital accounts in the recent global financial crisis.

The fact is that a strong state can curb destructive capital flows and defend a floating exchange rate from collapse.

The New York Times article acknowledges that:

As it turns out, while businesses predictably wince at Labour’s plans to increase corporate taxes, party advisers say many in the business sector welcome their commitment to investing in infrastructure, especially technology.

This is the point. Financial markets chase profits not ideological purity. A growing economy with innovative investment in public infrastructure is fertile for attracting FDI.

This is not to say that it should fix the exchange rate. Far from it.

Both flexible and fixed exchange rate regimes are subject to speculative attacks from financial players intent on seeking short-term gains.

Ultimately, the best way to stabilise the exchange rate is to build sustainable growth through high employment with stable prices and appropriate productivity improvements, even if the higher growth is consistent with a lower exchange rate.

The choice of exchange rate regime provides no defense against destructive capital flows. However, evidence shows that ‘sudden stop’ episodes are much more common in fixed exchange rate regimes.

In fact, it is often forgotten that the Bretton Woods system was ultimately derailed precisely by speculative capital flows that threatened the exhaustion of the foreign exchange and/or gold reserves of nations running external deficits.

It is also the case, that it was only capital controls that gave any semblance of currency stability during the fixed exchange rate period, especially in the various European arrangements that followed the collapse of the Bretton Woods agreement in 1971.

The other point relates to claims that a nation will run out of money if foreign investors lose confidence in the government, or, more to the point, dislike the policies it is pursuing.

This is also patently false.

For example, China does not fund the US government. It just invests the financial surpluses in US dollars it earns from its current account surpluses against the US economy. Instead of keeping the cash receipts within the US banking system, Chinese interests swap into a US-dollar denominated financial asset earning a return above cash.

No foreign investor funds any currency-issuing government.

Further, given a sovereign nation does not have to borrow anyway, global financial markets cannot influence the capacity of such a state to spend to advance domestic well-being.

Also, any exchange rate depreciation that might occur under a British Labour government as growth stimulates imports will change the fortunes of the traded-goods sector of the economy. Exports become cheaper in world markets while at the same time imports become more expensive.

Britain could expect its tourism industry to grow even further as a result of the currency depreciation. The depreciation during the GFC and then again after the Brexit referendum certainly has led to a rise in tourism.

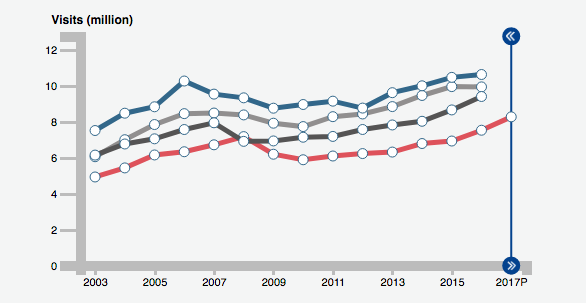

The British government tourist agency – VisitBritain – provides excellent data on British tourist flows and spending.

It shows that for the first-quarter 2017, total visitors rose by 9.88 per cent and their spending rose by 15.58 per cent over the year. So that is the Winter-quarter.

The following graphic (taken from their site) shows the time-series evolution for each of the four-quarters from 2003.

In July 2016, the UK recorded “its biggest-ever month for tourist visits” (Source).

Tourism is Britain’s “fourth-biggest service export, and one of … [its] … fastest growing sectors”.

Further, “The sharp drop in the pound has inevitably made tax-free spending attractive for overseas visitors.”

We also witness a rise in import substitution when the exchange rate depreciates, which stimulate local employment and relieve the cost pressure on local citizens.

Whenever the Australian dollar depreciates (as it does regularly), we go on holidays up the coast rather than to the ski fields of Europe!

What about the claim that the bureaucracy would undermine the British Labour government’s agenda?

The New York Times article writes:

Labour’s plans to restructure the economy represent a break with a neoliberal consensus of the past 30 years. This shift does have popular support, yet it might conceivably face institutional resistance. Britain’s civil service, which has met with the Labour leadership and which is democratically committed to political neutrality, could respond to populist left policies with a technocratic disposition toward continuity and slow, incremental change.

Possibly but not insurmountable.

And, finally, what about free trade agrements?

I considered Investor dispute resolution mechanisms in this blog – The case against free trade – Part 3 – which was one of four blogs I wrote about ‘The case against free trade’.

The conclusion is obvious.

These so-called ‘free trade’ agreements are nothing more than a further destruction of the democratic freedoms that the advanced nations have enjoyed and cripple the respective states’ abilities to oversee independent policy structures that are designed to advance the well-being of the population.

The underlying assumption is that international capital is to be prioritised and if the state legislature compromises that priority then the latter has to give way.

A progressive agenda would ban these agreements and force corporations to act within the legal constraints of the nations they seek to operate within or sell into.

Fairly simple in fact.

Conclusion

The sabre-rattling from the conservatives will always accompany the likelihood of a progressive government being elected. There are clear cases when capital has conspired to undermine a government it saw as threatening its position.

But usually the government has failed to use its own capacities correctly in these situations. For example, if the private sector goes on a ‘capital strike’ and reduces investment, the solution is simple. Increase public investment to improve essential services while the private sector gets over its uncertainty.

The point is that short of invading a nation with a military force, all capitalist interests have to work through the existing legal framework that is set by the legislative fiat of the nation state.

A Corbyn government would be able to resist any threats from self-interest capital interests to ensure its acted in the interests of all the people rather than just the few!

Reclaim the State book offer

Go to www.reclaimthestate.org – for discount codes.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2017 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Thanks for this Bill. Much appreciated. I hope John McDonnell and his team know this stuff. We’ll do our best to make sure they do.

Appreciate you’ve got other countries to think about but Anny chance you could comment briefly about on the implications of falling house prices in the UK? …as per this article:

http://www.independent.co.uk/voices/uk-house-prices-fall-housing-market-property-london-buying-selling-renting-britain-wont-cope-a7990496.html

Collapsing house prices would certainly trigger a panic among the property owning middle classes and will definitely be used by the mainstream media as a stick to bear a Labour government with

“Capital inflows that manifest as FDI in productive infrastructure are relatively unproblematic.”

The problems that do arise from it are an issue though

– there is a tendency for governments to chase FDI rather than see it as an alternative to the government doing the investment directly. So we then get ‘free trade deals’ that have investor protection clauses in them that override sovereignty.

– that leads to a ‘we need the foreigners money’ attitude rather than ‘It would be nice if we could learn from the foreigners skills and experience’.

– Once FDI is in place the asset is sold on to another set of foreigners who then switch the asset into extraction mode. If the exchange rate depreciates then they put prices up to maintain their profit in foreign exchange terms. This leads to a ‘marmitegate’ problem – where a product that is made locally from local supplies is hiked in price to avoid incurring an FX loss. Something that would not have happened had the asset been owned locally by somebody in the same currency zone.

– Since the point of a floating exchange rate is to allocate such losses, FDI can cause a problematic inflation feedback into the currency zone.

Rather than FDI it may be better to focus policy on sending the people abroad to learn skills and experience and then bring them back with fat juicy offers in local currency and state investment in their community. Which sort of seems to be the strategy of the Chinese and Indians.

I think Neil Wilson points out some of the potential problems with FDI. There is another big problem with foreign direct investment when that takes the form of companies purchasing large areas of productive land and using that mostly to extract and export. That type of thing is not relatively unproblematic at all, at least in the history of my country (US) towards quite a few Latin American countries. Or more accurately, it sucked for most of the people in those countries, not the US companies that owned the plantations and such.

Neil’s points are as usual well taken. As well as Bill’s, of course. But I fear that many read such things without knowing something essential:

The first and only really necessary line of defense, the only “capital control” needed is simply to have a floating rate currency. All the other stuff might be nice, but it is not necessary. The problems that the hottest money can cause are minor compared to the damage of fixed rates, and the systemic damage they cause to the domestic economy – high interest rates, austerity, unemployment + inflation etc.

As I have posted several times here, Franklin Roosevelt said: “The sound internal economic system of a Nation is a greater factor in its well-being than the price of its currency in changing terms of the currencies of other Nations.” Keynes, commenting on the message where he said that, said “magnificently right”.

Dear Bill

With regard to FDI, we should distinguish between brown-field investment and green-field investment. A lot of FDI is brown-field investment, that is, the take-over of existing companies by foreign investors. When foreigners take over Jaguar, for instance, they aren’t adding to the capital stock of Britain. A lot of cross-border transactions nowadays are brown-field investments. It intensifies the denationalization of capitalism, which can only further alienate the big-business class from their own country. The essence of globalist ideology is to liberate big business from any national loyalties and restrictions.

Another reason why a lot of people nowadays believe that a full-employment policy is impossible is the assumption that technology will soon make most existing jobs obsolete.

Regards. James

Labour High Command is a hotbed of virulent neoliberals who do not even realise the consequences of the nonsense they spout. They attempt to divert attention from the poverty of their macroeconomics by using the term ‘progressive’ in every sentence. The likes of McDonnell and Long-Bailey can be oft heard stating that ‘we must live within our means’ and ‘our spending program is fully funded by this that and the other tax change’.

The establishment has no fear of Labour which will easily be diverted to focus on ‘progressive’ social issues with neoliberals calling the macroeconomic shots. The sad fact is that dear George Osbourne and co are in the same socially progressive neoliberal quadrant.

From an environmental point of view, doesn’t the UK need to substitute home produced goods for the disaster of ‘mountains of crap from China’ which is largely poor quality? Flat lining wages and high housing costs have encourage the importing of cheap ‘crap’. If Labour wage share rises combined with Government ( as well as productive credit from banks) encouragement of businesses to produce more durable, high-quality goods then we could have more jobs and less wasteful imports.

I know MMT sees imports as a ‘benefit’ and I’m aware that this is purely an unqualified statement of fact -but in the case of Chinese imports the ‘benefit’ is solely in providing cheapness because of low wages/high debt culture in the UK.

“The first and only really necessary line of defense, the only “capital control” needed is simply to have a floating rate currency.”

That’s the debate point. The problem is that the dynamics are uncertain and badly modelled. For example there is a belief amongst certain other Post Keynesians that ‘central banks that target overnight rates are inevitably drawn into serving as FX dealers of last resort’.

For me that is a mistake due to a deficiency in the modelling of the clearing process. But that would only show itself once you stop using simplistic system dynamics abstractions and start using proper agent based models where you can actually see what an FX dealer is doing and how they would change what they are doing when you declare the policy “the central bank will not clear financial FX transactions and will resolve any institution that becomes insolvent via the following resolution procedure…”.

Expectations are not natural laws set in stone. If you alter the base expectation you change the structure.

Thanks for this timely post Bill. I attended your talk in Brighton and asked you a question on capital controls (but made a complete hash of it I’m afraid) – this is just the answer I was looking for. They are a factor in the Brexit debate that was, and still is, almost completely ignored.

Try Googling ‘Free Movement’ and ‘Brexit’ and you’ll find pages and pages of items addressing free movement of people – endless to-and-fros regarding the costs or benefits of EU and other migration. Tucked away in the list you’ll likely find a few pieces regarding the advantages of the free movement of goods and services, and whether or not the UK will be able to replicate or replace these outside the EU.

You might find the final of the ‘Four Freedoms’ mentioned in passing, usually only by way of context for the other three, however, it is the free movement of capital that is by some way the most important and destructive.

That any kind of integration with the ‘globalised’ economy necessarily demands opening the national economy up to completely unrestricted capital flows is simply taken as a given.

I’ve tried engaging a few of the prominent remainers over here on whether effective action on this could be possible within the EU, but so far have either been ignored or waved off with talk of building consensus or that it could be introduced at the borders of Europe (which would rather defeat the point I think).

The other question I have is how fast can Labour act once in power? How long does it take for neoliberal economic sabotage to have an impact? It only has to create enough turmoil for long enough to panic the electorate sufficiently to give political cover for a coup. Looming war could help the elite too.

Labour under Corbyn pose an existential threat to the neoliberal order not just in the UK but globally. As such they’ll throw everything they have at toppling or capturing a future Labour government.

My nightmare is it all gets out of control and fascism is born from the chaos.

To be honest, I’m pretty scared.

If I was in a Labour Government I would be far more worried about the capacity of the Civil Service to implement the manifesto than dealing with speculative flows of hot money. I am not saying Labour should not have a contingency plan in the back pocket to deal with the issue should arise, but the probability of it arising is fairly very low.

One of the main difficulties, however, that is clearly in view is that of inexperienced ministers have to deal with a Civil Service that has been both hollowed out and politicised by Tory Governments. One only has to look at how the Service is struggling with the daily business of Government not mention Brexit to see what a frail reed they are likely to be. One can already hear them saying we do not have the resources to deal with your issues as we are dealing with the consequences of Brexit.

The UK Treasury has been a standard-bearer for the failed policies of Austerity that have wrecked such misery upon the poor. They are not going to change their neo-liberal views overnight if at all. There is a myth in the UK which asserts that the Civil Service is a-political and simply responds to the directions of the elected government. It is just that; a myth.

If I were Jeremy Corbin I would think long and hard about the Civil Service

Whilst I accept most of what you say in this article, Bill, I am worried about your clear support of the Labour Party under Jeremy Corbin.

The one clear message that is coming out of their policy is that they aim to have Britain remain in the Single Market and the Customs Union. I was a Remainer before the referendum, based mainly (self-interestedly) on what I expected to be (and still do) a lot of pain during the transition from membership of the EU and the putting in place of trade agreements with the rest of the world, and the fact that there is a remote chance that the EU can reform. My compatriots voted to Leave, so that is what we must do. Continuing membership of the Single Market means we will have no say in how the EU progresses and, worse, we will have to comply with the horrors of Article 123 and probably the S&GP. We finish up in the worst of both worlds, so leaving altogether is the only option.

I cannot therefore support Labour, much as I like the rest of their policies.

“The one clear message that is coming out of their policy is that they aim to have Britain remain in the Single Market and the Customs Union.”

I wouldn’t say it is clear Nigel. Starmer is using Blairite triangulation techniques so that everybody hears what their prejudices want them to hear.

Since Labour won’t be in power when Brexit happens, they have absolutely no need to be clear on the subject. They can play all angles with word tricks.

The manifesto said, for example: “freedom of movement will end when we leave the European Union”. So if you never really leave, you never have to end it – hence the permanent transition period suggestion. But of course you can read it the other way if you are sure we are leaving the EU.

Nigel – if you don’t support Labour how do you hope for any change in the UK in the foreseeable future? I don’t notice much appetite for tackling neoliberalism in any of the other parties so we’re stuck with an imperfect Labour party or the continuation of Conservative rule.

I suggest that you join the Labour party and then you can use its internal democratic processes to influence policy. The more of us that do that the better the party will represent the people it seeks to serve.

Bill,

“Also, any exchange rate depreciation that might occur under a British Labour government as growth stimulates imports will change the fortunes of the traded-goods sector of the economy. Exports become cheaper in world markets while at the same time imports become more expensive.

Britain could expect its tourism industry to grow even further as a result of the currency depreciation. The depreciation during the GFC and then again after the Brexit referendum certainly has led to a rise in tourism.”

This is misleading. Calculate the trade elasticities yourself. After Thatcher’s ‘reforms’ Britain became an economic basket case. Depreciations lead to a worsening of the trade account now:

http://touchstoneblog.org.uk/2017/08/economists-free-trade-contradicted-todays-gdp-data/

This means that ALL of the adjustment will be borne by a fall in imports and, hence, in real income. Real wages will decline in lockstep with the sterling, just as they have in the past.

There’s no coming back from those Thatcher reforms. The UK is headed toward living standards of the Eurozone periphery. And decent policy will only be able to mitigate, not halt it.

Corbyn mentions the word “Nationalisation.”

And the average British Joe Bloggs simply isn’t ready to hear it.

As soon as they do, the elderly voter….the one that currently matters in terms of UK electoral success…..immediately goes back to the 1970’s, recalls industrial unrest, 3 day weeks, winters of discontent, power cuts, strikes, Healey borrowing from The IMF and so on. However, what really frightens them was the rampant inflation and pensioner poverty of the time. (A time when the elderly voter could be safely ignored by cynical politicians.)

Dear PP (at 2017/10/11 at 4:42 pm)

First, I only said that tourism would increase which is empirically founded. I made no mention of the overall external balance. So to accuse me of misleading readers is a step too far.

Second, I have looked at the “elasticities” – I examine them with every data release. And I wonder whether you have checked them yourself or have just relied on Geoff Tiley’s piece for your ‘informed’ opinion.

I would have checked myself if I was making these sorts of accusations.

The Tiley article you reference claims: “Over the year, the trade deficit has deteriorated (in cash terms) from £7.8bn in 2016Q2 to £8.9bn in 2017Q2.”

Well, ONS BOPS data shows different:

And ONS say:

And, the Current Account deficit was 7.1 per cent in the December-quarter 2015, dropping to 6.7 per cent in the June-quarter 2016, and it is currently (June-quarter 2017) at 4.6 per cent of GDP.

Then, consider the trade balance of the Current Account. In the September-quarter 2016, the deficit was 3.4 per cent of GDP. By the June-quarter 2017, it had fallen to 1.3 per cent of GDP, on the back of improving exports.

The article you reference also says that “Business investment has ground to a halt”. Which appears to be a falsehood.

ONS latest data on business investment:

All while the sterling was depreciating significantly.

I am not claiming that there will not be real income cuts as a result of the depreciation. It all depends on pass-through, which may not be as strong as it used to be. But I will say there will be innovations arising from such a shift in the terms of trade. Tourism is the most obvious one at the moment.

best wishes

bill

The bigger problem for currency depreciation paticularly in net importing countries

is increasing inflation.Not only will that undermine any wage increases but will be

a focus for a neo liberal backlash you know the framing “printing money causes inflation ”

More widely where globalization has had a negative effect beyond political capture has

been the fall in well payed (unionized) blue collar work.In much of the U.K. and USA the

problem is not the lack of minimum wage jobs but the lack of decent paid jobs .

Hi Chris – The report “Public opinion in the post-Brexit era: Economic attitudes in modern Britain” from the right wing think tank Legatum Institute and market research company Populus which you can access from http://www.populus.co.uk/2017/09/public-opinion-in-the-post-brexit-era/ seems to indicate British people are more ready to hear it than you think. The findings on support for nationalisation of various industries is shown in Figure 3.2a: on p15. They go on to analyse the results for railways, banks, gas, electricity and water by age which partly, but not entirely, as far as I can tell, confirms your views about older voters.

“The bigger problem for currency depreciation paticularly in net importing countries

is increasing inflation.”

Why? Why won’t the exporters to the UK have to keep their prices static in Sterling terms and take the loss in FX terms? Who else are they going to sell stuff to in a world short of demand?

I’m not sure where this idea that the UK is a permanent price taker comes from, but certainly we can affect it with policy. Whereas Thatcher went to the advertising and marketing industry and told them their propaganda was the future, we need to go to the Institute of Procurement and Supply and let them know they are the vanguard against inflation.

Neil Wilson,

I’m not listening to Starmer, I listened to Corbyn on the Andrew Marr show. I don’t recall exactly what he said but I was left with the clear impression that Labour policy is remaining within the Single Market. I am sorry if I misrepresent him, and I will do a bit of research to see if I can find any evidence. That said, politicians say one thing one day, one the next and do something entirely different when in power, so you never actually know until the deed is done.

Adam Sawyer,

I’m not very optimistic that root and branch members of the Labour Party really do have much influence on policy, but I take your point. No good moaning from the outside.

However, I am today meeting with the leader of a new political party which was formed in January who has been receptive about MMT in email exchanges. I am already a member of that party and voted for it in the last election. I’m not saying who they are until I fully understand their aims and whether I think they might consider formulating policies that use a MMT framework.

Neil Wilson,

Try this –

https://www.theguardian.com/global/2017/aug/26/labour-calls-for-lengthy-transitional-period-post-brexit

“Lengthy” in the article suggest 4 years, but it says Labour has not ruled out permanent membership.

Or this from the horse’s mouth –

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2017/aug/26/keir-starmer-no-constructive-ambiguity-brexit-cliff-edge-labour-will-avoid-transitional-deal

Specifically –

“Labour would seek a transitional deal that maintains the same basic terms that we currently enjoy with the EU. That means we would seek to remain in a customs union with the EU and within the single market during this period. It means we would abide by the common rules of both.”

I either want the UK to remain in the EU and seek to influence fiscal policy settings or to get the hell out ASAP. The former is now almost impossible without a further referendum.

Bill:

Have you seen this: http://www.independent.co.uk/news/business/news/universal-basic-services-idea-better-basic-income-citizens-social-housing-ucl-a7993476.html

When I saw the headline I thought maybe they were going to talk about a jobs guarantee, but no. Just increased public services free at the point of use but “paid for” by regressive taxation.

Nigel

Personally I hate party politics and I do disagree with some of the stuff Labour’s leaders are saying. However first past the post means we are stuck with one of the big parties being in government for the foreseeable future.

I’m part of a small but growing band of Labour party MMTers. I’m the only one in my Constituency Party (CLP) but I’m always trying to convert others. I’m attending an MMT meeting at UCL next week and I’ve persuaded a few from my CLP to join me, including one of our councilors. I’ve got another 600 members yet to convert.

I agree I don’t have much influence personally over the leadership, though even a lowly member such as myself was able to speak to John McDonnell at conference, if only briefly. Where members’ influence arises is in the aggregate. As such my job is to convert individual members and help them gain the economic understanding to feel comfortable attempting to convert others. That takes a long time. By comparison a fully fledged MMTer joining the party is immediately capable of converting others and therefore is a much greater addition than one new convert still struggling to understand the idea.

Therefore I’d strongly encourage you to join, get in touch with the rest of us Labour MMTers and help us spread the word among the party members. I’m not saying it’s easy or the only approach worth taking, just that I’m hopeful and that we could use your help.

You can friend request me in FB: I’m the Adam Sawyer with the “I’m voting Labour” flash on my profile pic and the antlers (don’t ask!). You can also search for the public FaceBook group: MMT for the British Labour Party.

I suppose the philosophy behind the unfettered FPI regime is that it is a way of ensuring that wealth flows to countries that are set up in a way that best allows wealth to prosper. That neoliberal system is aiming to have all countries competing against each other to attract and retain FPI. My personal view is that there is often a conflict between what favours short term portfolio performance and what favours society’s wider and longer term interests. However, in the UK at the moment, I guess to some extent we are “winners” in terms of attracting FPI and so we have something to lose by no longer winning at that. Labour is probably best off being upfront about taking a decision to possibly forego some of the “free lunch” that comes from being able to have a stronger currency and large trade deficit thanks to FPI.

Nigel,

Both of those go to my point. You can read either of those statements either way. From what I can see both main parties are sat firmly on the fence, but only the Tories have to get down at some point.

Bill,

The rise in exports in the UK are driven by a general rise in worldwide income. You can see this by looking at the growth in exports in other countries relative to the UK (grey bar is sterling depreciation):

https://i2.wp.com/fixingtheeconomists.files.wordpress.com/2017/10/uk-exports.jpg?ssl=1&w=450

We know for a fact that this is not due to a decline in price because export prices have risen [!] since the depreciation:

https://tradingeconomics.com/united-kingdom/export-prices

This is a pattern long noted in the UK – I’ve even spoken to the statisticians and they seem rather concerned about it.

I have estimated the elasticities myself, yes. Here are some other estimations that show the same thing:

http://www.etsg.org/ETSG2015/Papers/525.pdf

“The long-run level of exports appears to be unrelated to the real exchange rate for the UK.” (p21)

The UK economy has undergone a profound structural transformation in the past 40 years. It has shed its domestic industry and become tightly integrated into global supply chains. Any serious decline in the sterling – including the one that will likely be precipitated by Corbyn’s election – will lead to a dramatic fall in real wages (as has happened in every recent sterling decline).

The UK faces vastly falling living standards in the next 10-20 years. And good policy – including fiscal policy – will only be able to mitigate and potentially redistribute that decline, not halt it. I think that policymakers should go into this with their eyes wide open.

Adam Sawyer

Thanks for your recommendations. I’m not very proficient with Facebook but I’ll try and find you and the Labour MMT group. Good to hear it exists anyway. I was hoping to be at UCL but I’m afraid it isn’t possible.

The Argentina model of take over abandoned factories wont work high up in the value chain. An “abandoned” car factory can’t reopen under worker management, it’s a part in a complex value chain. Sewing machines/shuttles can be transported around the globe chasing the lowest payed workers. But that’s rare. In the beginning of the 80s the main value of fortune 500 companies was in fixed assets, roundabout 2000 it was all about immaterial values. Until the 80s the knowledge asset was engraved in fixed assets as factories and machines that where guarded carefully. Then the focus shifting to protect immaterial rights where the productive knowledge was engraved. The physical factory has become less important as value/capital carrier.

Strange arguments that depreciation Sterling won’t do nothing positive for UK exports, rather the opposite according to some. All countries with negative CA and foreign debt and trapped in IMF/WB web must do everything they can, and more, to devalue their costs, internal or otherwise. Germany is obsessed with internal devaluation, in the believe it boosts their export industry. Why do Sweden have negative interest rates, to boost the domestic economy, not at all, it’s alla about depressing the currency. Domestically it does what it can to have fiscal surplus.

But one can wonder if its all that effective, price elasticity is probably fairly great. As one can see overtime in the great currents of USD volatility. It affects but not as much as one could expect.

“Globalization” have made big companies global colossuses. A significant share of cross-border trade is inside these behemoths. An effect of neoliberal deregulation of bank/credit to be created out of thin air. The bigger the company, the larger financial flows and the more they have used the credit creating leverage to become global dominants.

Re effects of currency depreciation:

Over the last 30 years or so Canada has experienced very large currency swings: up 50%, down 33%, and everything in between. The effect on inflation has been almost imperceptible. Yes, the cost of fresh fruit and vegetables in winter and of foreign travel have gone up but overall the effect has been barely noticeable.

Neil Wilson describes what happened: to keep market share in our wealthy country, importers have mostly absorbed the effects of currency fluctuation except where mark-ups are very small.